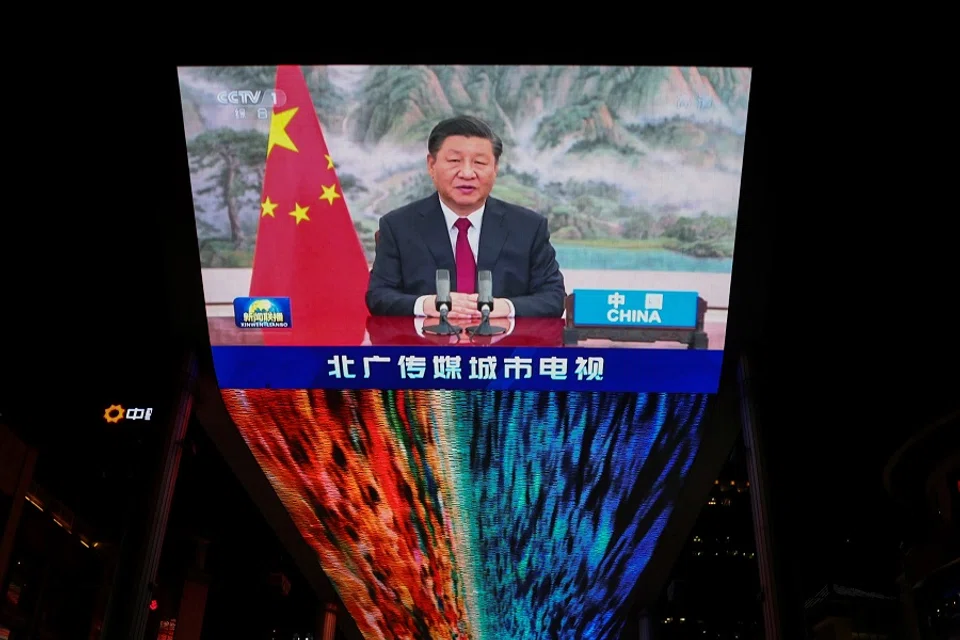

Xi Jinping's misguided return to ideology

China's reform and opening up era was precipitated by the disastrous Cultural Revolution, which was at a fundamental level an ideologically inspired revolutionary experiment. Its direct consequence was the "crisis of faith" in the late 1970s and early 1980s, and the open-ended reforms of the 1980s and 1990s.

For decades, the country was adrift in its political direction except for an unequivocal insistence on the ruling position of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Economically, China is in many aspects more capitalist than many capitalist economies, outcompeting them by large margins in the global marketplace. However, amid unprecedented prosperity, the CCP itself is decaying and disintegrating. It needs rejuvenation to hold on to power and govern effectively.

The financial crisis of 2008 ended China's eager emulation of the "best practices" of advanced capitalist countries and set it on a journey to find its own model and path. It now had to fill the hitherto empty bottle of Deng Xiaoping's slogan "socialism with Chinese characteristics", providing concrete answers to questions such as "What is socialism and how to build socialism?", "What kind of ruling party to build and how to build such a party?", "What kind of development to pursue and how to pursue it?" In other words, it was time for a new synthesis. Enter Xi Jinping to fulfill that mission.

Two contexts made Xi's resurrection of ideological orthodoxy almost inevitable - Leninist party rule and China's rise on the global stage.

With such a synthesis, Xi Jinping hopes to bring the entire party and the entire nation on the same page, so that they can act in coordination with one will, one direction and one goal - in other words, national rejuvenation. The result is "Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era", a new guiding ideology adopted by the 19th Party Congress in 2017, and subsequently enshrined in the amended Party constitution. Two contexts made Xi's resurrection of ideological orthodoxy almost inevitable - Leninist party rule and China's rise on the global stage.

The context of Leninist party rule

Also described as a "vanguard party", the Leninist party supposedly consists of a group of enlightened elites with better mastery of the "laws of history" based on the Marxist "scientific theory of socialism". As a disciplined and potent political organisation, the Leninist party facilitates historical progress towards that ideal society at the end of history.

Lenin pioneered waging revolution with a small but coherent conspiratorial group of enlightened revolutionaries in substitution for a large working class that Tsarist Russia lacked. Mao succeeded in carrying out a "proletarian revolution" on the back of China's vast peasantry. An ideologically inspired organisation was the key to the success of both.

The vanguard party is not subject to popular election because the party supposedly knows better than the general population, which is by definition "backward". Without the discipline imposed by periodic elections, the Leninist party is dependent on the official ideology that every party member has faith in and pledges loyalty to, as its raison d'être as well as the basis of rationalising its operation.

The condition of official ideology pertains directly to the integrity of the party and the effectiveness of one-party rule as a regime type. The following organisational imperatives have called for the return of ideology.

Mao pushed ideology much further than Lenin and Stalin had ever done, especially during his Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution...

Maoist 'ideological party building'

Mao's innovation in waging a proletarian revolution in a sea of peasantry is "ideological party building", i.e., creating a Marxist party by indoctrinating the poor peasants. For a long time, Stalin was suspicious of this idea and doubted if Mao was indeed a Marxist. But Mao did succeed in mounting an armed revolution that brought the CCP to power in 1949.

Upon the founding of the People's Republic of China, a sceptical Stalin sent Pavel Yudin, a trusted Marxist theorist and future Soviet ambassador to Beijing in 1950 as his personal envoy to find out about Mao, ostensibly to prepare the Russian translation of Selected Works of Mao Zedong.

In fact, Mao pushed ideology much further than Lenin and Stalin had ever done, especially during his Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution, in which he extended his proletarian revolution to the realm of political consciousness, turning it against the entire party-state establishment, which he regarded as the hotbed of a new bourgeoisie, in pursuit of his revolutionary ideals.

The weakening of the official ideology in the reform era caused the degeneration of the CCP, prompting Xi to put restoring ideological faith as the first priority of his massive effort at rebuilding the party. He reasserted for the first time in the reform era that "realising communism is the highest ideal and terminal goal of the party", and reprimanded those who dismissed communism as something which was impractical or which lay in the irrelevant distant future.

He [Xi] fought hard against the centrifugal forces that come with market-oriented reforms and the disintegration of central authority experienced by his predecessors.

Membership integrity and organisational efficacy

Franz Schurmann coined the term "practical ideology" to highlight the nexus between ideology and organisation in a Leninist party. According to Xi, faith in the communist ideal is the "calcium" in the spine of a communist party member, the deficit of which would cause "osteoporosis". That is, political degeneration, economic avarice, moral decay and decadence in lifestyle. The restoration of faith is the key factor that would allow a communist to stand upright politically and guard against all temptations in a capitalistic market economy.

In the Leninist tradition of "democratic centralism", Xi incessantly emphasises the party discipline of "upholding centralised and unified leadership of the party centre", and "individuals obeying the organisation, the minority obeying the majority, the subordinates obeying the superiors, and the whole party obeys the party centre". He fought hard against the centrifugal forces that come with market-oriented reforms and the disintegration of central authority experienced by his predecessors.

The CCP has a sprawling establishment of 4.86 million party organisations at the grassroots level, reaching every corner of society and economy in addition to the state. The linchpin holding them together is the official ideology, which furnishes the common identity to the 95 million plus party members that come from all walks of life. With this vast membership and sprawling establishment, the CCP regards itself as the machine that drives China's rise.

Legitimacy

Instead of electoral success, a communist regime gains legitimacy with a strategy of "winning people's hearts but not their votes". Here ideology plays a key role. In addition to the promise of a future ideal society, the ideology also prescribes an exemplary role for each party member as a vanguard or role model working toward that goal.

Xi was quoted as saying: "Why do some folks curse the communist party? Because some party members betrayed the communist faith. They are not real communists. They harm the masses in the name of our party and hence smear our party. They joined the party for private gains and are hollowing out the party." He believes that corruption is the key factor in the demise of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), emphasising, "The greatest politics is (winning) people's hearts, and [ideological] consensus is the energy source of our struggle".

The rehabilitation of Mao is necessary because Mao is a symbol of the CCP's legacy of "serving the people" and its spirit of sacrifice for national liberation.

The rehabilitation of Mao is necessary because Mao is a symbol of the CCP's legacy of "serving the people" and its spirit of sacrifice for national liberation. Mao said in 1945, "Since ancient times, there has been no group in China that, like the Communist Party, does not hesitate to sacrifice everything - no matter how many lives - for a big cause."

According to the figures released by the Supreme People's Court, between 1921 and 1949, there were 3.7 million recorded party-member martyrs and their surviving families who were receiving pensions and preferential treatment from the government.

Xi further built on Mao by asserting in his speech commemorating the CCP's centenary that "political power consists of the people and the people constitute political power. The CCP fought to gain political power but to retain political power is to retain the hearts and minds of the people."

He [Xi] has repeatedly emphasised that the CCP is built upon a shared ideology, not on aggregated material interests...

Unity upon diversity

The greatest challenge to the CCP in the reform era is perhaps the pluralisation of the Chinese society that comes with the marketisation of the economy. Today, party members hark from diverse class backgrounds, often with conflicting material interests. Jiang Zemin grappled with this reality by broadening the social basis of the party with his idea of the "Three Represents", while Hu Jintao advocated a vision of "harmonious society". Both are inclusive approaches.

Xi Jinping, on the other hand, has taken the Maoist road of ideological re-indoctrination. He has repeatedly emphasised that the CCP is built upon a shared ideology, not on aggregated material interests, and that ideological faith of party members takes precedence over their material interests.

Several times, he led the Politburo Standing Committee in a public ritual repeating the oath that every CCP member has to pledge when joining the party. "Why wasn't there a single man brave enough to stand out when the Soviet Union broke up?" asked Xi. "It is because the majority of the Soviet party members were fake communists. ... our party would be in terminal decline if we do not purge them."

The core diagnosis of Xi of China's problems, as well as his prescription for its future, is a missing soul and sagging spirit.

The context of China's rise

China's rise is the rise of a civilisational state on a truly global stage. It must compete with the well-established Western civilisation and must have something to offer to the world in order to be accepted as a rising superpower. In other words, this context has both national and global dimensions.

National spirit

The core diagnosis of Xi of China's problems, as well as his prescription for its future, is a missing soul and sagging spirit. It is true that reform and opening up have created enormous material wealth. However, public morality, social trust and personal integrity have sunk to new lows; corruption is like cancer penetrating the bone marrow of the party-state.

In Xi's mind, a nation without a soul cannot really rise, no matter how wealthy it becomes. Therefore, reviving the soul and elevating the spirit of the nation is a precondition to national rejuvenation. Here, Xi draws from two major sources.

The first is CCP's revolutionary legacy. Xi enumerated the serious consequences of the breakdown of ideological faith among party members: rampant corruption, extreme individualism, immorality, hedonism, money worshiping, superstition, fearing and respecting nothing, mocking Marxist orthodoxy and the communist ideal, embracing fortune-telling, seeking help from God, deities and qigong masters, moving family members and assets abroad to prepare for "jumping ship" at any moment, and so on. A nation ruled by a party in such conditions is hardly a source of inspiration for the world.

As the main force of national revival that has succeeded in overcoming great odds, the CCP is the main source of national spirit. Why were millions of party members and affiliates willing to lay down their lives to bring China where it is now? Xi believes that it was their faith in the party's cause.

In Xi's words, "[faith in] revolutionary ideals is loftier than the sky", and "a spiritual crisis is the most fundamental one underlying all other crises", including moral decay. However, the revolution of 1949 is very recent. It alone cannot define China's national rejuvenation as a long historical process.

Marxism is revolutionary and forward looking while China's cultural traditions are inherently conservative and look into the past for gold standards. Xi has to improvise to marry the two.

The second source is hence the renewal of China's five thousand years of cultural, philosophical and ideological traditions. Here Xi runs into the problem of integrating the two fundamentally incompatible traditions. Marxism is revolutionary and forward looking while China's cultural traditions are inherently conservative and look into the past for gold standards. Xi has to improvise to marry the two.

First, he claims that Marxism activated China's cultural traditions, breathing life into an ancient civilisation on its last legs. Secondly, he claims substantial overlap between the ideal of a communist society in Marxism and the Confucian ideal of a world of universal harmony all under heaven, where benevolence, justice and virtue prevail. Third, he also claims the heritage of the Maoist "serving the people wholeheartedly" in Confucian people-oriented philosophy, citing Mencius: "The people are the most important, the state comes second, and the ruler is least important of the three."

Last but not the least, Confucianism, Buddhism, Taoism and other cultural traditions of China are good remedies for the unwanted militancy of Marxism-Leninism and Maoism in peace-time development. By nature, Marxism discriminates along class lines, while the thrust of Chinese traditional philosophy is more inclusive and resonates well with some of the central policy themes of the Xi regime, such as harmony between man and man, man and nature, state and state; masses-centred administration; moral integrity as the first principle of governance and selection of officials; and his effort to revive traditional family values.

..."socialism with Chinese characteristics", it [CCP] believes, has a track record in solving such problems. Xi sees in this an opportunity to seek a leading role in world history.

Global turbulence

Xi rose to power at a time of acute crisis of liberal democratic capitalism, which he alludes to as "changes unseen in a century". To him, the West has lost both moral high ground and systemic superiority, especially after the 2008 Wall Street financial meltdown. He claimed on New Year's Day of 2013, right after assuming power that "the scenery is ever more beautiful on our side", full of anticipation of a resurgence of socialism worldwide.

The CCP declares that "socialism is to solve problems that other systems could not resolve", and "socialism with Chinese characteristics", it believes, has a track record in solving such problems. Xi sees in this an opportunity to seek a leading role in world history.

To establish the lineage of the CCP to the world's socialist movements, Xi divided the history of socialism into six stages: 1) early utopian socialism pioneered by Thomas Moore, Henri de Saint-Simon, Robert Owen, Francois Marie Fourier and others in the 16th to 19th centuries; 2) scientific socialism established primarily by Marx and Engels; 3) Lenin's breakthrough in the Russian October Revolution; 4) the Stalin model of building socialism; 5) Mao's exploration in the first three decades of the People's Republic of China and 6) the CCP's socialism with Chinese characteristics in the reform and opening up era. He thus plugs what the CCP is doing now back into the 500 years of international socialist/communist movement.

In other words, it is now upon the CCP's shoulders that rests the historical mission to prove the vitality, viability and superiority of socialism, and hence lead humankind to its manifest destination in communism. This sense of historical mission is clearly stated in a pair of articles published in the CCP's mouthpiece People's Daily in early June 2021: "Socialism has not let China down" and "China has not let socialism down".

Xi-ism is in many ways misguided. It is Maoist in its thrust but nothing in it has surpassed what Mao had attempted but failed.

Prognosis

With the demise of fascism and communism in the 20th century, and the crisis of neo-liberalism in the early 21st century, China appears to be the only major alternative still standing. That alone gives China the confidence to forge ahead and blaze a new path for mankind. Xi-ism, while inheriting the Marxist teleology of history, is characterised not by theoretical innovation but by instrumentality.

On the flipside, Xi-ism is in many ways misguided. It is Maoist in its thrust but nothing in it has surpassed what Mao had attempted but failed. Xi's fixation on and affinity with the Stalinist system tends to blindside him of other options in policy and institutional solutions.

As a result, his resurrection of orthodoxy also brings back some of the problems of 20th century communism. It is questionable whether his ideological reformulation and institutional building, in his zeal to restore the integrity back to the Leninist party, have made enough allowances to accommodate the diversity and dynamism that come with a market economy.

Xi also misconstrues the reform and opening up success: the things Xi puts at the top of his agenda - restoring the Marxist faith, strengthening party discipline, re-centralising power, fighting corruption, beefing up state-owned enterprises, tightening information control, purging Western influence, restraining freedom of speech and cracking down on dissent and so on, played no positive role in China's developmental success. They may indeed strengthen CCP rule, but at the cost of social vitality and economic dynamism.

Xi's left turn has placed the CCP in an ideological position that makes it hard to fence off more radical forces from the left. It has created a political environment that is nurturing radical forces incompatible with much of what the reform era has accomplished, that may erode or even reversing those achievements. It has also set China on a collision course with Western liberal democracies that it is unprepared to deal with.

Related: Why Xi Jinping's bold experiments with socialism are commendable | Can socialist China change society's value orientation and triumph over the ills of capitalism? | China turning inward? China has always been a civilisation unto its own | Can the CCP avoid the Stalin's curse under Xi Jinping? | A new paradigm needed: China cannot achieve 'common prosperity' with Marxism and class struggle | Rise of China's CCP and demise of USSR's CPSU: A tale of two communist parties