ASEAN 2020: How to swim in the choppy waters of the US-China conflict

2019 was the year in which the US-China conflict that disrupted the East Asian regional order intensified. In mid-January 2020, the two countries signed a phase one agreement to ease their trade dispute. Under this agreement, China will increase imports from the US by US$20 million from 2017 levels and remove tightened regulations on intellectual property, while the US will lift its designation of China as a currency manipulator. However, the US did not lift tariffs on Chinese imports.

The most significant point at issue in the conflict between the two countries is the battle for supremacy in world politics. The bottom line is that the structure of a hegemonic US and China's challenge to that hegemony has not changed. Despite the repeated heightening and easing of tensions, the US-China conflict will continue to shake the region and the world.

Southeast Asia will continue to attract attention as one arena in which such conflicts between the two countries play out. However, as well as paying attention to the way that the US and China approach these conflicts, our focus should be on the response of ASEAN countries and their efforts to secure their independence and profits.

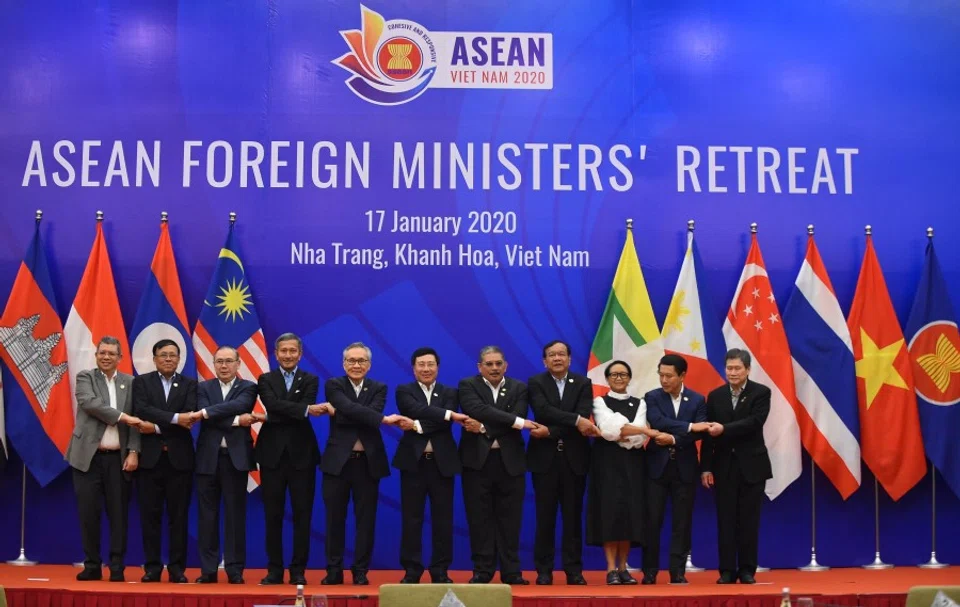

At the ASEAN Foreign Ministers' Meeting (AMM) held in January this year, concerns were raised about the South China Sea issue. The ASEAN chair Vietnam has shown a hardline stance toward China on this issue for many years, and although this reflects its intentions, the fact that ASEAN has called for self-restraint in respect of China's continued expansion of activity in the South China Sea since last year is important. This expression of concern will prevent China from conveniently justifying its actions.

Furthermore, a press statement from the chairman following this AMM indicated his intention to hold a special ASEAN summit in the US in March. Disappointment over the fact that not only did President Trump not attend the ASEAN-related summit last November, but also sent a low-level official in his place, is still fresh in the minds of ASEAN nations. However, the US and ASEAN maintain a basic cooperative relationship, the US-ASEAN maritime exercise conducted in September 2019 being one example. The special summit in March this year will provide an opportunity to repair the severely damaged US-ASEAN relationship at a symbolic level.

However, ASEAN nations cannot seek a closer relationship with the US alone, nor does the US have the unqualified support of all ASEAN nations. For example, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad criticised the US's killing earlier this year of General Qassem Soleimani, commander of Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), while avoiding any mention of President Trump by name. Mahathir has long shown a hardline stance toward the US, so criticism of the US may be expected. However, the ASEAN area has many Muslims, including Malaysia and Indonesia, home to the world's largest Muslim population. Iran is a Shiite nation, while the majority of Muslims in Southeast Asia are Sunnis. Even if followers of the Shiite and Sunni sects are not completely united in their positions, it is important to be mindful of the potential for US actions in the international community to act as a provocation to at least some ASEAN countries or people in those countries.

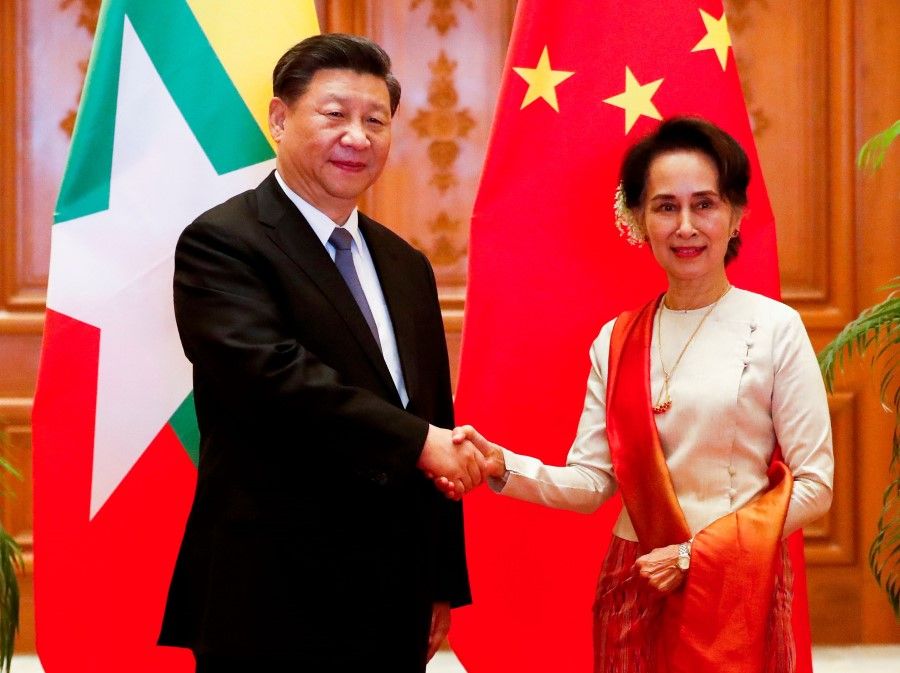

Also, Chinese President Xi Jinping made an official visit to Myanmar, timed to coincide with the AMM. This is an important move in two respects. First, it is the first visit of a Chinese president in nineteen years, seen as opportunistic in light of the widening distance between Myanmar and the West, not least in part due to the latter's criticism of Myanmar on the Rohingya issue. It is also an attempt to bring about a closer relationship with Myanmar, or a restoration, if you will, of relations between two countries that had stagnated following Myanmar's shift to civilian rule.

It should be noted that China has a track record of strengthening relations with resource-rich African countries that the West views as committing violations of human rights. After the meeting, President Xi and Aung San Suu Kyi, State Counsellor of Myanmar, issued a joint statement that included the construction of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor. Further, at the meeting San Suu Kyi called for support from China for the Myanmar government's stance on the Rohingya issue.

The US-China conflict is shaking up politics in the region. However, the actions taken by ASEAN countries will also determine future trends.