China: Sole preoccupation of US foreign policy

Chip Tsao says that US foreign policy has for two decades focused on threats such as the "axis of evil" and global terrorism. With the coronavirus escalating US threat perceptions of China, will the rising dragon now dictate its every move?

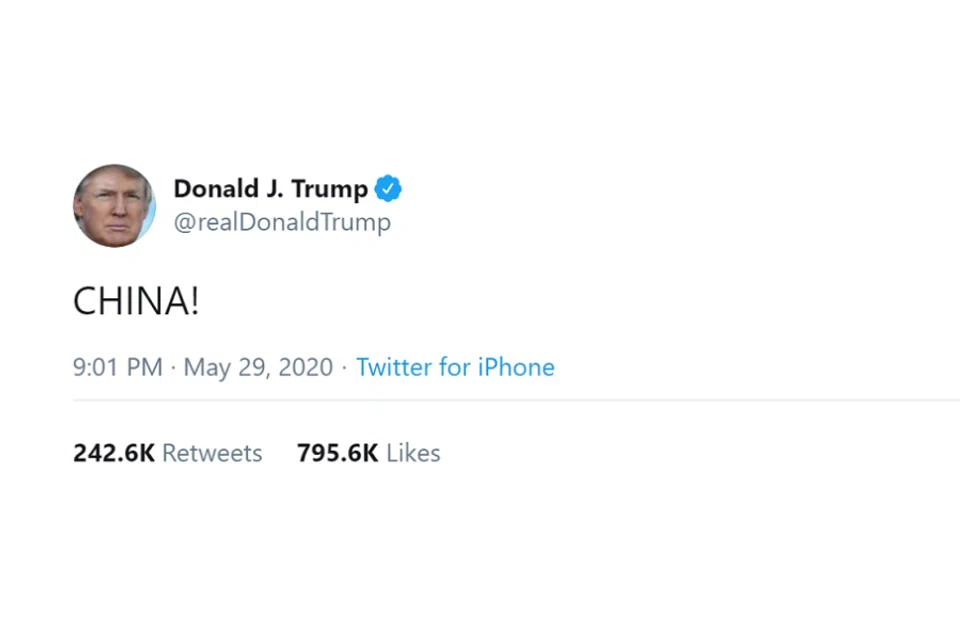

The spread of the "Wuhan coronavirus"* is both a blessing and a curse to US President Donald Trump.

It is a blessing because China is indirectly helping to answer the call Trump made during his presidential campaign for US enterprises to move back to the US. Without the virus, US manufacturers and investors would probably only realise their "folly" in an extreme calamity. Initially, the "China threat" theory was something people couldn't care less about. But the coronavirus made a crash landing on American soil, threatening each and every family in the US. The China threat is now more real than the shadow of Islamic terrorism Americans lived under.

China has surpassed ISIS and Iran to become publicly recognised as the US's top threat.

Of course, China is aware of this. It has kept its death toll figures low as much as possible - as of now, China only reported over 4000 deaths - to move down the global coronavirus death toll chart, even as other countries like Italy and the UK climb the charts due partly to the transparency of information. It seems like China's attempts at concealing or lowering the numbers are not working in its favour, because the numbers of the US and Europe are ballooning. The virus has become the best ammunition to propagate the China threat.

20 years ago, Kenneth M. Pollack, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, published The Threatening Storm, which considered Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein an extremely dangerous person. He convinced the country's liberals that another world war would break out if Hussein was not ousted.

After Saddam Hussein, US foreign policy was preoccupied with Osama bin Laden and the aftermath of 9/11. After the second Iraq war, came the threat of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS). After Trump announced that Islamic terrorism has been nearly wiped out, a Xi Jinping-led China came along. With the aid of the "community of shared future for mankind" concept (Note) and the virus putting it into practice, China has surpassed ISIS and Iran to become publicly recognised as the US's top threat.

Some say that the US needs an imaginary enemy to maintain its military expansionist forces. In the same vein, China also needs its 50 Cent Party (a colloquial term referring to internet commentators hired by Chinese authorities) to make the US its top target of hate.

To some extent, China and the US are interdependent, each having their own needs. Yet, the globalisation of the coronavirus seems to have made the US's imaginary enemy theory come to life. The "Chinese virus" crashed through the lands without warning and broke into the White House at lightning speed. All at once, a top aide to the US vice president, as well as the personal assistant of the President's daughter fell victim.

According to a report by the US House of Representative's Task Force on Terrorism and Unconventional Warfare released in 1992, an Iran-controlled strategic axis from Tehran, Baghdad to Damascus, and stretching from the Mediterranean to Africa, was forming part of a larger "Islamic Bloc".

In the same period, Anthony Lake, then national security adviser under former US President Bill Clinton, warned about the emergence of "backlash states" - namely, Cuba, Iraq, Libya, Iran, and North Korea - that posed a threat to US interests and ideals. These states hated the US for a wide array of reasons but not a single one of them alone could become a threat. Moreover, they lacked cooperation between one another.

In 1998, the total GDP of these countries was only US$165 billion - not even one-third of the US's military budget then. Later on, former US President George W. Bush named Iraq, Iran and North Korea the "axis of evil". (NB: In 2002, John Bolton, then US undersecretary of state for arms control and international security, declared that beyond the "axis of evil" countries, Syria, Libya and Cuba were other "rogue states" bent on acquiring weapons of mass destruction.)

For three months, the public domain has little discussions on the threat of Islamic terrorism - its daily reports are about the so-called "coronavirus".

America's "axis of evil" theory developed into variants such as "Islamo-fascism" theory. It is ready to deem Iran its imaginary enemy, strangling and annihilating it a step at a time.

Unexpectedly, the Wuhan coronavirus sprang up, disrupting the US's prior foreign policy calculations based on its "axis" theory.

For three months, the public domain has little discussions on the threat of Islamic terrorism - its daily reports are about the so-called "coronavirus".

Neither Iraq nor Syria has export trade relations with the US. But China has.

Yet, none of the countries in the old "axis of evil" or the "beyond axis of evil" lists have productive forces. Neither Iraq nor Syria has export trade relations with the US. But China has. The US can impose economic sanctions on Iran, but it is technically extremely difficult to do so to China.

Now, just as the globalised economic structure is regrouping, the US decides to pull out at the last minute. This is like reaching the last round in a game of mahjong (a popular tile-based game in Hong Kong) when you have already prepared a set of winning tiles, only to have it switched up in a messy turn of events.

But time is running out for Trump. He only has three months. China has launched a massive propaganda campaign, attempting to make the World Health Organization (WHO) its frontline ambassador. So then, the US has to abolish the WHO. Although Democrat presidential candidate Joe Biden has vested interests in China, he is left with no choice but to take a tough stance.

In the US's urgent foreign policy reset, the "axis of evil" notion has regressed into playing a minor role - the leading role goes to China.

*This translation has kept to Chip Tsao's use of "武肺" in the original Chinese text.

This article was first published in Chinese on CUP media as "唯一的主角".

Note:

In his statement at the General Debate of the 70th Session of the UN General Assembly in September 2015, President Xi Jinping detailed the creation of a community of shared future for mankind as building partnerships in which countries treat each other as equals, engage in mutual consultation and show mutual understanding; creating a security architecture featuring fairness, justice, joint contribution and shared benefits; promoting open, innovative and inclusive development that benefits all; increasing inter-civilisational exchanges to promote harmony, inclusiveness and respect for differences; and building an ecosystem that puts Mother Nature and green development first.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)