The mysterious garden hidden in drawers

Writer Shen Jialu looks at the origins of the storage space that is a drawer, and how it holds hope, joy and secrets throughout time in Chinese and Western cultures.

Drawers are where collected items are categorised and where secrets begin.

First, a little-known fact: when did drawers become part of Chinese furniture? Some say that drawers were invented by the strategist Zhuge Liang of the Eastern Han and Three Kingdoms dynasties — sorry, that is farce.

Used since ancient times

Since ancient times, countless inventions and creations have been credited to the “Four Heavenly Kings”, both mythological and real — Xuanyuan (轩辕, known as the Yellow Emperor 黄帝), Shennong (神农, born Jiang Shinian, known as the Yan Emperor 炎帝), Ming dynasty architect/carpenter Lu Ban, and Zhuge Liang. This was a result of the need to pass on culture.

In the 1960s, a mirror box with two small drawers was unearthed from a tomb in Changzhou dating back to the Southern Song dynasty. However, drawers probably came into popular use in Chinese furniture in the Ming dynasty.

During the time of the Northern and Southern Song dynasties, when “art was life and life was art”, big literary names such as Su Dongpo, Lu You and Li Qingzhao used containers such as boxes, chests and tubes that were easily carried around. They also used transparent frames for string-bound books, but some space would be left unfilled, enough to fit vases, incense burners and stones. These were placed on either side of the book shelves, separated by the vast ocean of words and literature.

In the Ming dynasty, during the early rule of the Longqing Emperor, the ban on maritime trade was lifted and overseas trade was restarted, leading to significant economic development in coastal cities.

Chinese rosewood furniture from the Ming dynasty, such as simple, elegant desks and tables, sometimes had one or two hidden drawers built in at the joints below the surface, subtle yet beautiful.

The introduction by Zhou Qiyuan to the Ming dynasty book An Account of the Eastern and Western Oceans (《东西洋考》) said: “Merchants from all directions gathered, and the market was prosperous... precious goods were loaded, and exotic items were aplenty.”

The market flourished and trends changed; as cultural researcher Wang Shixiang said, “People started to pay attention to furniture.” In literary circles, the variety of writing instruments was staggering, almost to the point of mania.

Just like that, Chinese classical furniture entered its golden age, and drawers quietly became an integral part of daily life. Drawers made furniture more functional, changed people’s storage habits and thinking, and expanded the aesthetic space. Of course, this process was not without its twists and turns.

Chinese rosewood furniture from the Ming dynasty, such as simple, elegant desks and tables, sometimes had one or two hidden drawers built in at the joints below the surface, subtle yet beautiful. Cabinet drawers were ornate, with white copper handles mostly bearing chiselled decorations, but which lessened the artistic value.

In his Treatise on Superfluous Things (《长物志》, a book on architecture and interior design), Ming dynasty scholar and designer Wen Zhenheng staunchly believed that “the most elegant cabinet is bare, with just one shelf” (橱殿以空如一架者为雅).

The book cabinet is commonly known as the round-corner cabinet (圆角柜) or the flat cabinet (面条柜, lit. “noodle” cabinet). After opening the two doors, you can see a small drawer between the upper and lower sections, with a pair of dangling copper handles.

In his Treatise on Superfluous Things (《长物志》, a book on architecture and interior design), Ming dynasty scholar and designer Wen Zhenheng staunchly believed that “the most elegant cabinet is bare, with just one shelf” (橱殿以空如一架者为雅). If there is a special auction of vintage furniture, please go and appreciate their wonders.

Drawers in the West

The use of drawers in Western furniture came no later than in China; it might even have been earlier. Foreigners also like to boast that drawers originated in ancient Greece — at least they appeared widely in Gothic-style furniture during the Middle Ages.

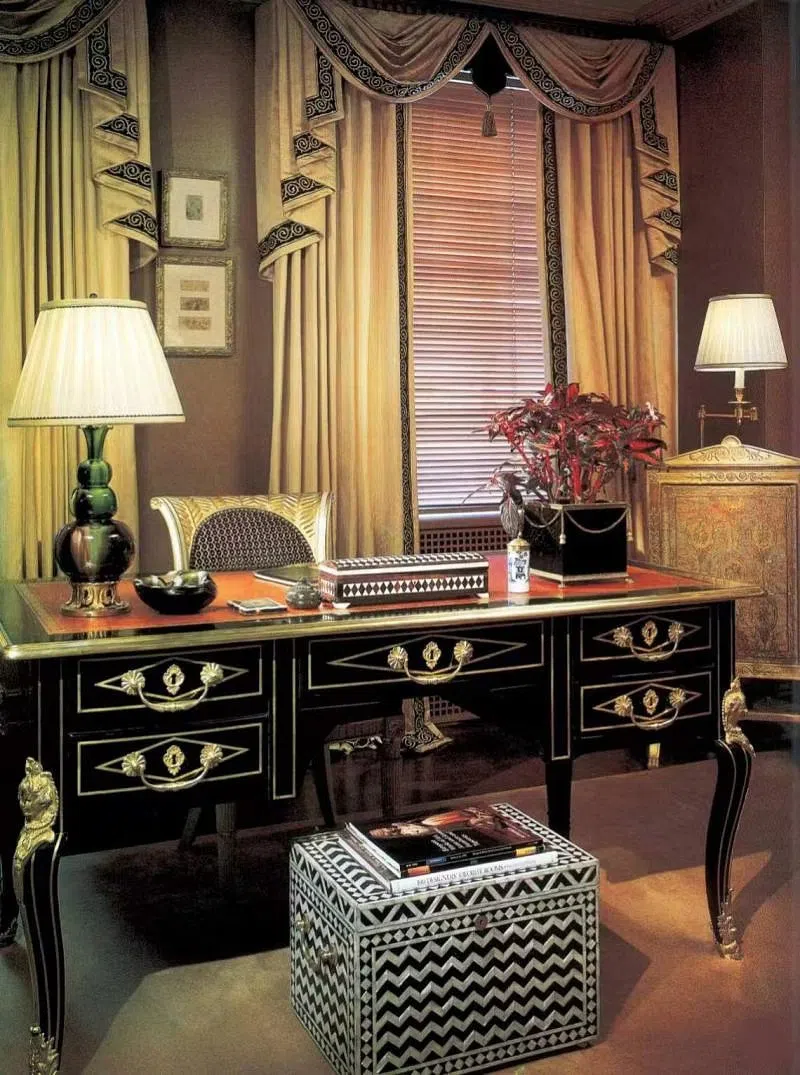

Europeans later indulged in the complexity and luxury of the Baroque and Rococo styles, as drawers provided designers and craftsmen with opportunities to create intricate carvings.

A widowed countess might hide her unfinished poetry in her drawer, while a general might leave his will and a dagger engraved with a family crest in his drawer before going to war. Then came a generation of writers such as Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald who wrote climaxes where a handsome, straight-nosed man with a determined gaze pulls out a revolver from the drawer.

... the Chinese openly recite love poems, put drops of blood into wine bowls as vows, and listen to the call of the sword hanging on the wall in the still of the windy, moonless night.

In vintage furniture stores in the West today, you can still see desks specifically designed for women, featuring curved lines and cabinets integrated with a tabletop, with little drawers to store jewellery and letters.

A young, love-struck maiden writes in her diary, puts away her quill and ink, blows out the candle, pulls shut the roll top strung together with thin wooden strips, and locks the cabinet with a small key. The blush on her cheeks gradually dissipates as the moonlight shines in the garden and the wind gently rustles in the trees — it is the spiritual fortress of Honoré de Balzac’s Eugénie Grandet or Leo Tolstoy’s Natasha Rostova.

Meanwhile, the Chinese openly recite love poems, put drops of blood into wine bowls as vows, and listen to the call of the sword hanging on the wall in the still of the windy, moonless night.

Even the steady “eight-immortal table” (a square table built to seat eight people) became a mahjong table with drawers on all four sides.

A drawer of one’s own

In the process of urbanisation, drawers play a crucial role in welcoming new life. However, as living spaces become smaller and relationships become more tense, managing daily life requires precision. Families with many children need enough drawers to store their miscellaneous items.

I was in the second grade when I got a drawer. Inside I kept my kaleidoscope, army chess, cigarette cards and student handbooks.

The adults’ drawers were even more intriguing, with household registration books and ration coupons on top of a brown paper envelope containing old photographs that gave me a glimpse into what the world was like before I was born. My mother wore a mink coat, leather boots and gold-rimmed spectacles — was my family once wealthy? My mother explained that the items were borrowed from the photography studio.

Industrial civilisation and secular culture also come through in drawers. For example, in Shanghai-style furniture, especially the complete set of redwood furniture designed for the middle class, the number of drawers became a measure of economic value.

Even the steady “eight-immortal table” (a square table built to seat eight people) became a mahjong table with drawers on all four sides. In the 1970s and 1980s, it was fashionable to have five drawers on a bureau, with the top one necessarily locked, as if it were the final stronghold.

Era of open drawers without locks

Nowadays, the living conditions of Shanghainese have greatly improved, and some families have 20 or 30 drawers. However, relying on a single, lockless wooden box to safeguard private property and privacy is risky, so financial assets, stocks and financial products are stored in cards or mobile payments accounts, while secrets and photos are kept on smartphones.

Old paintings, calligraphy or the Golden Monkey Stamp can be locked in a safe alongside property deeds and insurance contracts.

No one writes in diaries any more, and sending letters in secret is only seen in period dramas. Modern furniture has entered the era of open drawers without locks.

This seems like a victory for civilisation — not that drawers and locks would think so. Drawers are still territory that each person should guard, the mysterious garden where the mind can roam freely, and the canoe that will bring you to the other shore.

Some people organise their drawers neatly, while others leave them messy (most people are like this), but no one wants others (including their parents) to pry into or invade their territory.

In a locked diary within a little drawer, there lie our thoughts that are as vast as the spring and autumn tides, as well as our dignity and hope.

A good drawer should allow hope to go in and joy to come out.

My granddaughter is in fifth grade, and she has five or six drawers in her own home and our home, which is the beginning of self-management. However, I have been unable to buy a small bookcase with a lock.

One day, she was writing in her diary and immediately pressed her little hand to cover the notebook when I approached to give her a thumbs up. She said, “You can’t look, this diary has a lock!”

Wonderful — the awakening of personal consciousness must be affirmed. The more open society is, the more dense information gets, and the more important privacy becomes.

I hope she sticks with writing, learns to confide in herself, looks far into the distance, and imagines the future. In a locked diary within a little drawer, there lie our thoughts that are as vast as the spring and autumn tides, as well as our dignity and hope.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “抽屉,你的神秘花园”.