Savouring youtiao in Shanghai: Plain, with soup or pork-stuffed?

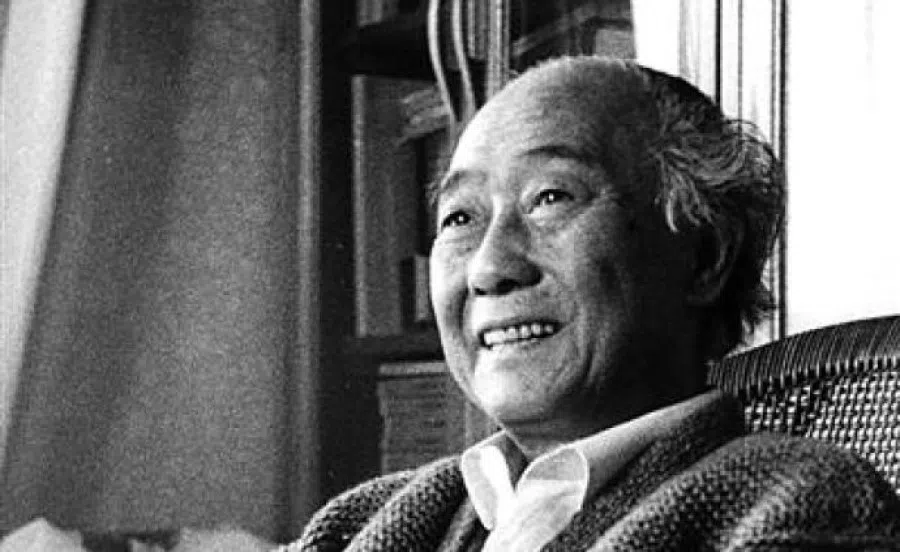

Writer Shen Jialu describes his love for youtiao - a simple yet versatile food item, suitable for any occasion. Of course, many others share a common pleasure in youtiao, not least the writer Wang Zengqi, who claimed to have come up with the unique recipe for pork-stuffed youtiao.

Nobody can say no to Chinese fried dough sticks, or youtiao (油条). Whether in ramshackle old streets, crowded markets or a tiny stall on a street corner, setting up a wok to fry youtiao will definitely attract a throng of customers who eagerly watch as the youtiao swimming in the wok swiftly expands and darkens into an enticing golden brown, rising like the morning sun over the common folk.

Youtiao sold by the kilos

Among the "Four Heavenly Kings" of a Shanghainese breakfast, youtiao and dabing (大饼, fried pancakes) are inseparable lovers. But I must also point out that while it is difficult to sell dabing without youtiao - both northerners and southerners agree that dabing must be stuffed with youtiao to taste good - youtiao can stand on its own, alongside eager allies such as jianbing (煎饼, Chinese crepes), cifan (粢饭, glutinous rice rolls), egg pancakes and scallion pancakes. Boosted by youtiao, jianbing can truly live up to its name, while cifan and egg pancakes can find their core value and their place along the West Lake.

Youtiao is also found in northern China, where it probably originated. In his book Hometown Neighbours (《老乡亲》), writer Tang Lusun wrote about the breakfast in Beiping (now Beijing): "The dough of the youtiao is cut into long strips with a slit made across the middle. It is then pulled by hand and fried into long oval shapes. This makes them more elegant and easier to stuff into shaobing (烧饼, flatbread) compared with the towering pillars seen in Taiwan."

I must add to Tang's already detailed description: after cutting the dough into long strips, the cook needs to pick up two small strips and stack them together, press a small seven- or eight-inch steel rod into the middle to create a small groove, then twist it into a braid in a bed of flour with a flick of the wrist, stretch it to the appropriate length to fry, and then pinch off the ends. The cut surfaces of the two strips cannot meet, otherwise the youtiao will not puff up; this technique is called "parallel strips" (并条).

... It seems that the people in Qingdao also buy youtiao by the kilos and do not mind eating them cold.

Why do I stress this point? Because it is the key to the success or failure of youtiao, and the premise for making pork-stuffed youtiao (油条搋肉).

I have to reiterate: northerners are hearty youtiao eaters. They purchase it by the kilos: "Sir, give me one kilogram of youtiao!"

Forty years ago, I was walking the streets of Qingdao with my girlfriend around four or five o'clock in the afternoon, and some elderly women were frying youtiao by the roadside. The fried youtiao was piled up on a wooden board like a little mountain. My girlfriend and I wondered: could it be for some celebration?

We could not resist asking one of the women, who loudly replied, "We're selling them early tomorrow morning!" It seems that the people in Qingdao also buy youtiao by the kilos and do not mind eating them cold.

Shanghainese are very shrewd when buying youtiao. They buy one or two at a time, and they have to be fresh out of the wok, sizzling with hot oil so that it pierces your very core when held in the hand; that way, it is crispy and fragrant, or like what writer Eileen Chang described: that mouthful of heat when biting into a youtiao.

Youtiao left standing in wire baskets are like sidelined attendees in a ballroom, ignored unless you are in a hurry to grab breakfast before work. Usually, when business slows down, the cook would refry the cold youtiao. And if they are refried again the next day, they become firm and crunchy like mahua (麻花, fried dough twists). The Shanghainese call aimless idlers "old youtiao".

When things get tough, a single youtiao can tide over the whole family. Pull the halves apart, cut them into pieces, dip them in soy sauce, and eat them with porridge.

A treat during tough times

Old youtiao stuffed in cifan tastes excellent, but the cooks only serve it to regulars; most people do not have the privilege of tasting it.

When things get tough, a single youtiao can tide over the whole family. Pull the halves apart, cut them into pieces, dip them in soy sauce, and eat them with porridge.

As expressed by fellow writer Xi Po in his piece "Breakfast" (《早餐》): "If I had the luck to be sent to the food stall at the end of the alley to buy youtiao for a meal, the whole family was sure to wait for me to return and eat together. Breakfast then was definitely not as sumptuous and nutritious as it is now, but it was certainly warmer and happier."

Such is the usual shrewdness and family harmony of the Shanghainese. But under the pen of writer Liang Shiqiu, it became something to talk about. See how he describes it in his essay "Porridge" (《粥》): "Breakfast was a pot of porridge, a few colourful side dishes to share, a small piece of fermented tofu sitting by itself in the centre of a plate, a small handful of peanuts scattered sparsely over the dish, one youtiao cut into several pieces piled into a small mound on the plate, and one whole century egg swimming in the soy sauce dish. One could not say it was not sumptuous, but those accustomed to a richer diet would feel hard done by, if it wasn't considered ill-treatment."

Mr Liang must have eaten youtiao sold by the kilos in Beiping and Qingdao. He surely could not imagine that even today, dipping youtiao in soy sauce and paired with porridge remains a delightful treat to awaken the taste buds.

Cut a strip of youtiao into pieces, toss it in the bowl, add dried shrimp, seaweed, soy sauce and chopped scallions, pour in hot water, and voilà - a bowl of soup. Drizzle in a few drops of sesame oil, and it doesn't taste half bad.

No soup? Youtiao to the rescue

There are even tougher moments - when soup is missing from the meal. For Shanghainese, a meal is not complete without soup. This is when youtiao comes to the rescue.

Cut a strip of youtiao into pieces, toss it in the bowl, add dried shrimp, seaweed, soy sauce and chopped scallions, pour in hot water, and voilà - a bowl of soup. Drizzle in a few drops of sesame oil, and it doesn't taste half bad.

After the resistance against Japan was won, the impoverished writer Wang Zengqi came to Shanghai and taught Chinese at the private Zhiyuan Middle School (致远中学). On Sundays, he visited old bookstores, and strolled around Chenghuang Temple, the French Park (now Fuxing Park) and Zhaofeng Park (now Zhongshan Park). He had two friends in Shanghai: artist Huang Yongyu and writer Huang Shang. He would also often have coffee and a chat at writer Ba Jin's residence in Huaihai Fang (淮海坊, previously Joffre Terrace or Xiafei Fang 霞飞坊). He probably had youtiao in Shanghai, observing the locals while waiting for it to come out of the wok.

Wang lived at the school. I recall a detail in his short story Sunday, when the upstairs residents threw water from their washbasin right into the courtyard, creating a racket. "As I was packing my bags before leaving Shanghai, I found over an inch of white fuzz growing on the back of the mat on the small iron bed!" During the rainy season, this was the gift of the "mystical city" (魔都, a nickname for Shanghai from a 1924 novel by Shofu Muramatsu) to the "Shanghainese drifters".

After his passing, the people of Gaoyou put together a "Wang Zengqi feast" based on his food articles, and many eateries advertised such feasts to attract customers.

To commemorate the 100th anniversary of Wang's birth, Gaoyou city built a memorial hall, which reportedly won an international design award. Wang spent his youth in Gaoyou, then wandered through Yangzhou, Kunming, Shanghai and other places before getting married and settling in Beijing in 1950. Many of his food essays are set in Gaoyou, Kunming and Beijing, showing deep emotional attachment with the most detailed descriptions of his hometown.

In his later years, he returned to his hometown three times, leaving behind many good stories. After his passing, the people of Gaoyou put together a "Wang Zengqi feast" based on his food articles, and many eateries advertised such feasts to attract customers.

Last year in Gaoyou, I got to taste pork wrapped in cattail (蒲包肉), Wang-style tofu (汪豆腐, braised tofu dish), grass oven cake (草炉饼), fish slices with golden floss (金丝鱼片), stewed eggs in fried rice (炒米炖蛋) and braised tiger shark (红烧虎头鲨) - Wang seemed partial to tiger shark soup. Unfortunately, other famous dishes such as salted vegetable and Chinese arrowhead soup (咸菜慈菇汤), tofu in salted duck egg sauce (朱砂豆腐) and stewed radish with dried shrimp (开洋煨萝卜) were unavailable as they were not in season.

But when I went back to Gaoyou at the start of summer, at the Huifu Jinling Hotel, I finally got to eat what I was after: pork-stuffed youtiao.

Wang-style tofu and pork-stuffed youtiao

Surprisingly, amid the unassuming Wang Zengqi feast, pork-stuffed youtiao has been given a radiant name: "Sun and Moon Shine" (日月同辉). This is a combination dish of Wang-style tofu paired with pork-stuffed youtiao.

I ate Wang-style tofu the previous year and wrote about it. The soybeans and water quality in Jiangsu's Lixiahe area are excellent, and the dried tofu used in Huaiyang cuisine - such as for boiled shredded tofu (大煮干丝) or blanched finely shredded tofu (烫干丝) - is produced there; the quality of tofu is also outstanding.

The main ingredients of Wang-style tofu are tofu and pork blood. In the cooking process, both vegetarian and non-vegetarian oils are used, and the flavour is enhanced with other ingredients such as dried shrimp, mushrooms and lard. After boiling, the dish is thickened twice to keep the tofu from breaking up or burning. Wang-style tofu is a familiar, homey dish, and when paired with freshly baked grass oven cake, it makes for an idyllic scene of laughter over food and drinks, which is worth savouring.

The word "stuffed" (搋, chuai) is a local term in Gaoyou, meaning to clear out something or dig out a hollow and then refill it with something else. The youtiao is cut into pieces an inch and a half long, stuffed with minced meat and other ingredients, and fried again in oil until it becomes crispy. It is eaten hot with tomato sauce or sweet pepper sauce, or paired with Wang-style tofu, for a combination of dry and saucy foods. However, it is a bit of a stretch to say they symbolise the sun and moon; if Wang were alive, he would surely object.

... after the Huanghe Road and Zhapu Road food streets came up, youtiao stuffed with pork or shrimp became the everyman's food, cheap and good. Wang claimed to have come up with it, but I disagree.

In his piece "Old-time Flavours: Cooking" (《老味道·做饭》), Wang wrote: "I came up with stuffing meat into refried youtiao; I could apply for a patent. Cut the youtiao into pieces an inch and a half long, hollow out the inside with your finger, stuff it with minced meat, scallions and pickles, and refry it in oil. Youtiao contains alum, which gives it a more distinct flavour than spring rolls. Refried youtiao is extremely crispy, and the crunch can be heard for miles around."

I love youtiao, and by extension, youtiao stuffed with pork. In fact, Shanghainese have been making this dish for a long time, simply calling it what it is. My family has made it many times just to use up leftovers, for a change in taste. And after the Huanghe Road and Zhapu Road food streets came up, youtiao stuffed with pork or shrimp became the everyman's food, cheap and good. Wang claimed to have come up with it, but I disagree.

Wang's friends from Gaoyou who received him on his return said that he loved to visit the market and cook. When unexpected guests came and stayed for a meal and there was nothing prepared, he would work with leftover youtiao, stuffing them with some chopped-up minced meat and pickles, frying them again in oil, and it would become a side dish that would satisfy everyone. The line about the reverberating sound of the crunch is reminiscent of Li Bai's poetic style; after all, a family feast is all about the atmosphere.

Amid the exaggerated noise of a table full of foodies chewing pork-stuffed youtiao, I seem to see a childlike smile.

Wang also used leftover youtiao to make soup. In a letter to linguist Zhu Dexi, he wrote: "Extremely smooth, like Nanjing's Chinese mallow (also somewhat like watershield)."

Under his pen, a simple homemade youtiao soy sauce soup was instantly elevated. Yes, he was always one to make the best of a bad situation!

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as "汪曾祺的油条搋肉".