Of spring and wild vegetables in Jiangsu

Writer Shen Jialu takes us through the various wild vegetables available in certain parts of China, with their unique flavours and associated dishes. Truly, there is nothing like a robust dish made with all natural ingredients.

There is a poetic saying: "Wild vegetables have no hometown." Since ancient times, wild vegetables have flourished in tandem with the human population, but the situation in the post-industrial era is somewhat depressing - do wild vegetables still grow in our hometown?

Standing in the city among its high-rise buildings, we may find public green spaces with lush grass and beautiful scenery within a 500-metre radius, but any traces of wild vegetables would be scarce.

Our next generation may have the fortune to taste matsutake mushrooms, truffles, caviar, bluefin tuna and so on, but it is rare to come across wild vegetables in the true sense. Vegetables that should be growing freely according to their genetic makeup have long been tamed into obedience, growing prettily in greenhouses where it is springtime all year round, quietly awaiting harvest.

So, the saying can also be: like wild vegetables, our next generation has no hometown.

Shepherd's purse: the ambassador of wild vegetables

When we were young, fish and meat rarely appeared on the dining table, but humble wild vegetables had the opportunity to shine. For instance, shepherd's purse. Straight out of the market, each leaf is covered in moist mud, exuding the freshness of dew and frost. Shepherd's purse and tofu soup with shredded pork, or stir-fried shepherd's purse with bamboo shoots, are the first seasonal dishes with which to embrace spring.

Shepherd's purse and pork dumplings is a dish where housewives get to show off their skills. Blanch and finely chop the shepherd's purse; it will be slightly dry, but adding a few cabbage hearts will moisten it. Leftover nian gao (sticky rice cakes) from the New Year soaked in water, sliced and stir-fried with shepherd's purse and shredded pork to share with the family is also an affordable springtime snack.

Subsequently, I came across some wild shepherd's purse with large, broad, jagged, purple-edged leaves growing over a foot tall in some empty land on the outskirts. Local elders used them to make shepherd's purse and pork dumplings, which seemed like dredging boats floating around in a large pot, cooked for personal consumption and not for sale.

In the outskirts of Shanghai, shepherd's purse and pork soup dumplings are as big as a baby's fist. I have to eat two or three each time I visit Qibao Old Street. One bite and the intoxicating breath of spring bursts through. Once, an elderly man I shared the square wooden table with boasted that he was a local and came every week, eating up to ten pieces when he had the appetite for it.

In Jiangnan's folk customs, on the third day of the third lunar month, elderly women wear shepherd's purse flowers on their heads, which is said to improve eyesight - hence, they are also called "bright eye flowers".

Shepherd's purse can be eaten until early summer, and people in Shanghai put it in soup with yellow croaker.

Shepherd's purse shoots are slightly red with a light purple tinge, and chewing it releases a mouthful of fragrance, while feeling like a game of resistance for the teeth. The writer Wang Zengqi mentioned in a short story the shepherd's purse with dried tofu dish from his hometown Gaoyou: "Mix together blanched and finely chopped shepherd's purse, Jieshou dried tofu cut into small cubes, and dried shrimp. This dish can be served at banquets, just mould by hand the cold shepherd's purse into a pagoda shape, and topple before eating."

The phrase "topple before eating" is vivid indeed.

Shepherd's purse can be considered the image ambassador of wild vegetables. "Who says shepherd's purse is bitter? It is as sweet as water chestnut."

Our ancestors discovered the sweetness of the roots of this vegetable 2,500 years ago, and that palate became part of the Chinese people's genes. In Jiangnan's folk customs, on the third day of the third lunar month, elderly women wear shepherd's purse flowers on their heads, which is said to improve eyesight - hence, they are also called "bright eye flowers". Placing shepherd's purse flowers on the stove is also said to ward off ants.

Even today, people in Suzhou still refer to shepherd's purse as wild vegetables, and I have eaten shepherd's purse dumplings and balls in the little market on Fengmen Old Street.

... when a well-respected official of the local area steps down from office, villagers will present a plate of Indian aster as a symbol of their hope that he would stay on.

Indian aster is even more wild

Indian aster feels even more wild. Their fragrance is intoxicating after being blanched in boiling water and finely chopped; mixed with smoked bean curd paste and drizzled with sesame oil, it is a seasonal vegetable with character.

Restaurants offer this cold dish when spring arrives, packed into small bowls and pressed firmly, then placed in white porcelain dishes. If a few wolfberries are buried at the bottom of the bowl, they are revealed as red dots amid a sea of green once plated. Indeed, wild vegetables should be vibrant.

Indian aster (马兰头, ma lan tou) was originally called "horse-stopping heads" (马拦头) in Chinese. It is said that horses would stop dead at their tracks to eat Indian aster by the roadside, and the rider had to wait until the horse was full before continuing. So, when a well-respected official of the local area steps down from office, villagers will present a plate of Indian aster as a symbol of their hope that he would stay on. Some people later thought "horse-stopping heads" sounded too crude, so they changed the second character of its name, replacing 拦 (lan, stop) with 兰 (lan, orchids).

Wild Indian aster has a hint of bitterness to it. When eaten as a cold dish, it can do with a little more sugar. As a child, I kind of hated the taste, neither sweet nor salty. Nowadays, agriculturalists have filtered out its bitterness, leading to an irreversible slide into mediocrity, which is regrettable.

My mother used to blanch Indian aster, spread them out on bamboo trays to dry in the sun, and then put them in jars after three days. In the summer, she would cook pork belly in a rich red sauce, with the full fragrance preserved.

Mugwort from the rural areas along the Yangtze River in Jiangsu is the most tender and fragrant. Mugwort sprouts are short and full of weeds, growing just in time for the puffer fish to appear.

Taming wild vegetables

Did you have a chance to eat purple amaranth 20 years ago? It used to grow with abandon everywhere, and farmers would cut it to feed the pigs. Later, its edible value was discovered, and it was brought into the city - stir-fried with minced garlic, its smooth texture and a hint of numbness made it unique.

Then there are also sweet potato vines and pumpkin vines, which can be stir-fried. They may not be very tasty, but no one has complained about it ever since it became a trending dish.

One can still find tamed wild vegetables such as mugwort. Mugwort from the rural areas along the Yangtze River in Jiangsu is the most tender and fragrant. Mugwort sprouts are short and full of weeds, growing just in time for the puffer fish to appear. Chefs in Jiangyin often use mugwort to line the bottom of a basin when cooking puffer fish, as it is said to have detoxifying properties.

As the saying goes: in February, there are reeds, in March there is mugwort, and in April and May, they are used as firewood. Even wild vegetables have their seasons; they should be eaten early. Mugwort can be stir-fried with dried or fermented bean curd, or with Chinese sausage, which people in Shanghai also love.

Once, I ate wild water bamboo in Changshu, which was finer and longer than the usual water bamboo I was used to. Stir-fried after being cut into strips, it was slightly fibrous but had a very rich flavour. Stir-fried wild water bamboo with chunks of dried radish and pickled mustard greens, drizzled with sesame oil, was unexpectedly delicious.

I fell in love with wild arrowhead at first sight. The bulbs were even smaller than Ningbo tangyuan, with a slightly red skin and a long stem. When bitten, it released a hint of the raw taste of a stream at night. The writer Shen Congwen described its taste as "elegant"; it must have been wild arrowhead.

... the early Tang poet Chen Zi'ang went west from Yangguan to Zhangye, and the local guards respected him as a literati, inviting him to eat "good vegetables", which was wolfberry leaves. - Ji Yuan, Writer, Suzhou

In recent years, one can also find wolfberry shoots in the local vegetable market. Every year, I ask my wife to buy a bunch. Stir-fried plain or with bamboo shoots and shitake mushrooms, they have a slightly bitter but clear flavour. When stir-frying wolfberry shoots, there is no need to add water or cover them, and there is no need for much sugar.

The Suzhou writer Ji Yuan wrote in his book (《江南风情好 菜蔬清如诗》, lit. in charming Jiangnan, the vegetables are clear as poetry) that the early Tang poet Chen Zi'ang went west from Yangguan to Zhangye, and the local guards respected him as a literati, inviting him to eat "good vegetables", which was wolfberry leaves.

Ji also believes: "Wolfberry leaves are a genuine vegetable in Zhangye in northwest China, and they are a premium vegetable, probably because there is a shortage of green leafy vegetables there."

Recently, at a "new Huaiyang" concept restaurant in Shanghai's Caojiadu area, I had garland chrysanthemum stems stir-fried with shrimp paste, a traditional home-style dish from Sheyang bursting with natural wild flavour and wok hei (镬气, meaning flavour imparted by the heat of the wok).

I was also pleasantly surprised by a small cold plate of plain salted garland chrysanthemum leaves. As a wild vegetable that grows by its own devices by the seaside, it thrives in crevices, nourished by seawater. It gets no more than half a foot tall, simple and nondescript, verdant and moist, with a salty taste.

According to the store manager from Yancheng, when there is a shortage of green vegetables, children by the seaside would gather to collect salted garland chrysanthemum leaves, filling a large basket in half a day, which could be eaten raw, or blanched and tossed in a cold salad. Its crisp texture and unique fragrance made me feel grateful for the first time I tasted it.

Cattail is usually simmered in milk or braised with dried shrimp - in this instance, it was baked with wild garlic, with whole garlic cloves slightly browned, and then flavoured with goose oil from Rendeux in Belgium. No one could resist it.

Cattail: a 2,000-year history in cooking

The tender stem of the cattail plant is the part used for cooking. It can be found buried in the mud at the bottom of a river and is ivory-white when it emerges from the water. The people of Huai'an have the good fortune of using cattail stems in their cooking; it is not found in Shanghai, and many self-proclaimed foodies do not know of it.

It has been used in cooking for over 2,000 years - the ancient book The Rites of Zhou has records of "minced cattail paste" (蒲菹), while a Ming dynasty poem describes eating tender cattail with fresh carp. However, this item is extremely delicate, and the locals gather, sell and eat it on the same day; getting to eat it is a blessing.

I tasted cattail for the first time over 20 years ago in Huai'an, and was amazed by its unique taste. I wrote an article about it, and my little shoutout to cattail has been shared in many media outlets and books. The cattail I had was brought in from northern Jiangsu that day, still covered with glistening dew. Cattail is usually simmered in milk or braised with dried shrimp - in this instance, it was baked with wild garlic, with whole garlic cloves slightly browned, and then flavoured with goose oil from Rendeux in Belgium. No one could resist it.

In Shanghai, green rice dumplings are usually coloured and flavoured with mugwort juice. In Liyang and its surrounding areas, it is a tradition to mash the local variety of mugwort - known as mao bi bi cao (毛鼻鼻草, lit. hairy nose grass) - and extract the juice to be mixed with glutinous rice flour, then flattened and wrapped over stuffing to form the dumplings. The stuffing includes local pork, snail meat and diced water chestnuts, making it both rustic and elegant, with a unique flavour. The Japanese emphasise being one with the soil, and the people of northern Jiangsu do it well too.

What Liyang locals call mao bi bi - scientific name Pseudognaphalium affine - has many other common names in Chinese, including Qingming grass (清明草) or Qingming vegetables (清明菜), Buddha's ear grass (佛耳草) or cotton vegetables (绵菜). The whole plant is covered with white woolly hair, the leaves are small like chrysanthemum leaves, and it blooms all year round with tufts of small yellow flowers. Even now, it is still used by workshops to make cloth dyes, giving shirts and skirts an antique charm.

In the spring of 1999, I was in Taizhou for an interview and unexpectedly tasted wormwood. As a child, when I suffered from fever and vomiting, doctors at the hospital made me drink wormwood soup, and I recovered in three days. But eating it as a cold salad was a first for me. Blanch, rid the excess water and chop finely; add salt, sugar and sesame oil, and voilà - drizzling vinegar works too. It tastes slightly bitter and leaves a refreshing taste in the mouth.

Locals make porridge with it too, adding sugar and red dates, which makes it suitable for people with jaundice and hepatitis, as it is said to have a certain therapeutic effect. Later, I learned from the Compendium of Materia Medica: "Even now, on the second day of the second lunar month, the people of Huai'an still pick wild wormwood seedlings and mix them with flour to make wormwood cakes."

Fortunately, bamboo is still holding on in the wild, worthy of the reputation of being the "number one vegetable". Seeing bamboo shoots breaking through the soil on the mountain always brings me joy.

Bamboo holding on in the wild

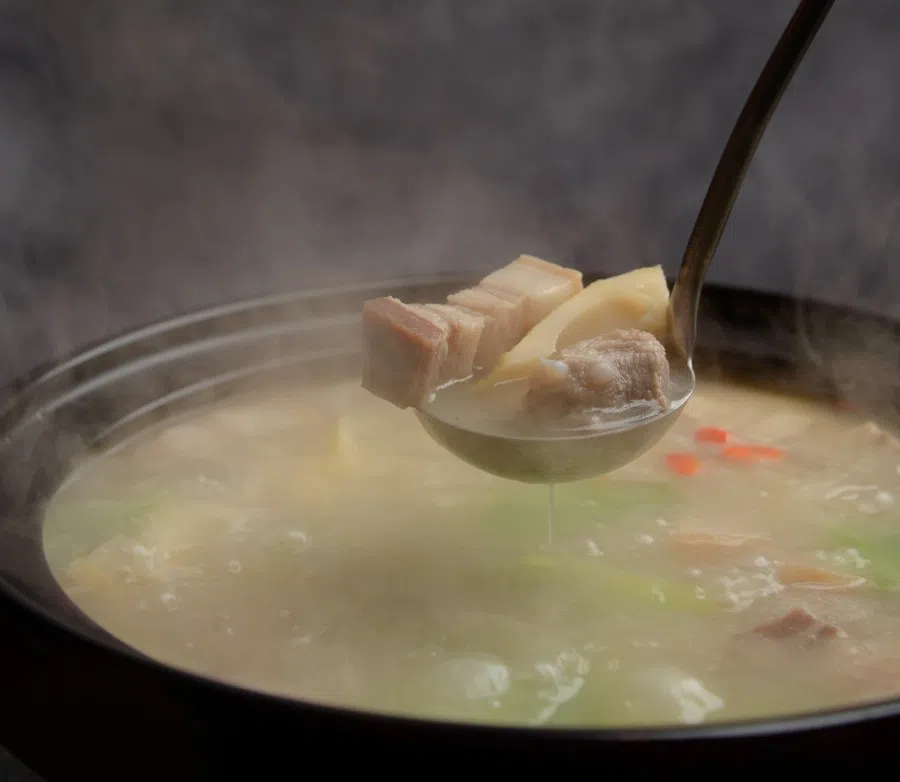

"When you start trying to find wild vegetables to cook with rice, it's the second lunar month in Jiangnan." Early in the morning, my wife went to the vegetable market and bought five bamboo shoots and two celtuce (celery lettuce/stem lettuce). Peel the celtuce and bamboo shoots, cut them into small pieces, and cook them together with salt-cured pork from Nuodeng, black pork belly from Jinhua, and beancurd skin from Jiangyin in a claypot, for a meal of yanduxian (腌笃鲜, a Jiangnan cuisine of bamboo shoot soup with pork).

Keep the celtuce leaves; pick out the tender leaves, lightly rub them with salt, squeeze out the bitter water after ten minutes, finely chop them, then add some diced salted pork and cook them into rice dishes. With its red and green hues and fragrance, it is delectable.

When cooking celtuce leaves with salt brine tofu, the celtuce leaves should be thoroughly sautéed in old oil. Leave a little soup, and the oil will give the edge of the plate a golden sheen, making the dish one fit for the gods.

Each human advancement comes at the cost of sacrificing a sense of poetry. In order to meet the needs of population growth, wild vegetables have gradually lost their innate wildness; some have even had to drift far from their natural habitats. At the same time, humans have been caring for them, protecting them from pests and diseases. May wild vegetables be sweeter, more fragrant and more abundant throughout the seasons, flourishing endlessly.

Fortunately, bamboo is still holding on in the wild, worthy of the reputation of being the "number one vegetable". Seeing bamboo shoots breaking through the soil on the mountain always brings me joy. The old poem goes: "Bamboo shoots sprout new like calves' horns, bracken shoots grow like a child's fist. When you start trying to find wild vegetables to cook with rice, it's the second lunar month in Jiangnan."

One night just after a spring shower, I was walking alone on a soggy path towards the depths of a bamboo grove. The hometown that I dreamed about rose before my eyes; the scent of earth and rotting leaves made me awake and excited, as an egret, startled by my footsteps, flew into the darker depths. I suddenly thought: how lonely the moonlight would be without the dancing shadows of the bamboo!

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as "江南春早野蔬香".