Taiwan art historian: My Aquarian friend Hualing who embraced everyone [Part 1]

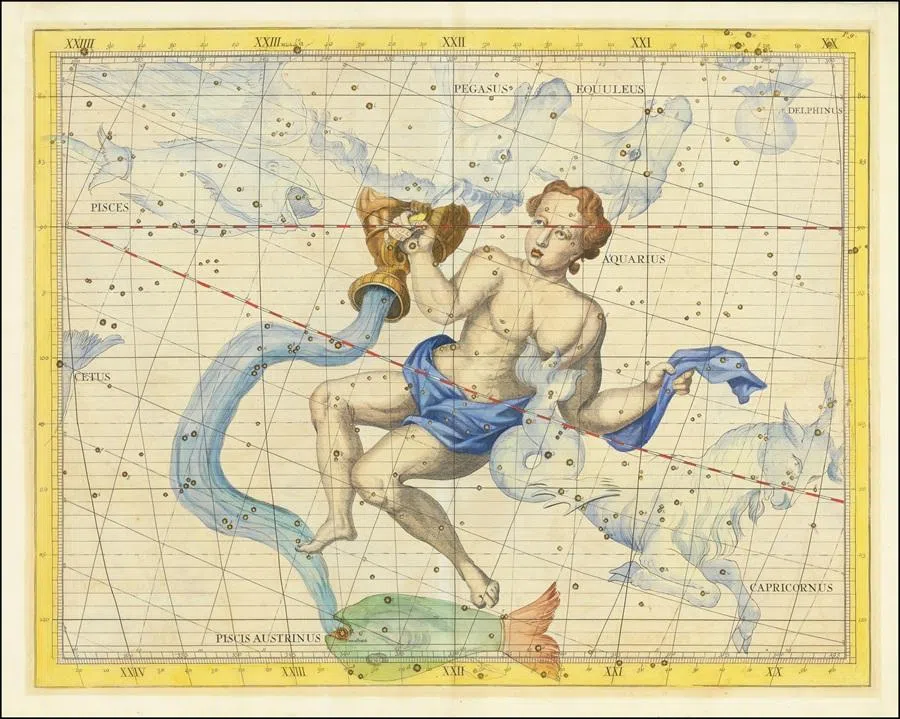

Taiwan art historian Chiang Hsun remembers his time in Iowa, US, with Hualing Nieh Engle, reminiscing on her ability to embrace people from all walks of life — a perfect example of an Aquarian. Such is the breadth and depth of the Aquarius’s rushing waters, endlessly flowing, with the water bearer’s energy always being given away to all living creatures.

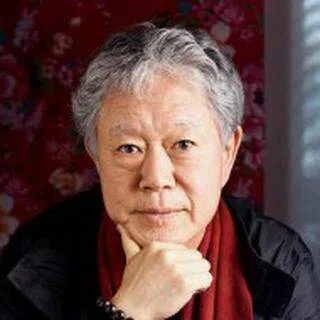

Hualing Nieh Engle left the world, just as she was about to turn 100.

The news said that she was born on 11 January 1925. I checked with her, and that was the old lunar date, so she was actually an Aquarian. I smiled and said to her, “Of course you’re an Aquarian.”

I have always had a special connection with Aquarians. Father and Mother were both Aquarians, along with many of my closest friends. I later discovered that I have Venus in Aquarius in my birth chart. Sometimes, when I gaze at the shimmering Venus in contemplation, I wonder if there is some cosmic force quietly pulling the threads?

Aquarian’s happiness onto others

I know a man from Kaohsiung who works as a hair stylist, does tattoos as well, and blends perfumes from all sorts of plants. His Facebook is rather amusing — sometimes he goes by Benson, other times the surname “Chiang”. The friends around him, men and women alike, are all non-Asian.

He once gave me a small bottle of perfume. When I asked him for the formula, he sent me this: “Top notes: bergamot, white grapefruit. Middle note: rose. Base notes: sandalwood, cedarwood.” He then sent over a handful of photos of the plants on his balcony — different varieties of roses among them.

I asked him, “This is Kaohsiung?”

He replied, “Yes!”

I suppose Aquarians carry a kind of innate cheerfulness — they create their own happiness and make people around them happy too.

Aquarians live in a little magical world of their own, indifferent to the names of cities or countries.

I got to know this Aquarian man with nary a trace of “Kaohsiung” about him. Still, in my hopelessly worldly way, I asked about his origins, parents and bloodline. He told me he was a foundling, abandoned by the roadside, and taken in and raised by “Granny”.

I carefully observed his facial features: he has a high nose bridge and long, fine brows, but his hair was dyed blonde and he had on bright blue contact lenses. Coupled with his Frida Kahlo-esque tattoos, I could not guess anything about his ancestry. Alright, I will just take his “foundling” story for now.

His current boyfriend is from Latin America — I forget whether it was Peru or Colombia — and Benson speaks remarkably fluent Spanish with him. On New Year’s Eve, he sent me a photo of him cooking in his house filled with a dozen or so foreigners, all raising their glasses to wish me a happy new year in every language imaginable.

His house reminded me of Hualing’s house.

I suppose Aquarians carry a kind of innate cheerfulness — they create their own happiness and make people around them happy too.

However, that’s not always the case. That night, he suddenly texted me: “Can I talk to you?”

I said “OK” and my phone rang. I heard him sobbing. He sobbed and sobbed. I did not speak. After the Aquarian finished crying, he said, “Thank you, laoshi (老师, meaning ‘teacher’).”

New Year’s Eve was over, and a new year began.

When she ran the Iowa International Writing Program, writers from all over the world came to her home; that house hung with African masks perched high above everything.

A laughter that could split mountains

Sometimes in my stillness, I find myself missing Hualing — how she spent her life taking care of so many people. When she ran the Iowa International Writing Program, writers from all over the world came to her home; that house hung with African masks perched high above everything. In autumn, with leaves falling and bare branches stretching to their tips, you could gaze out over the plains, where a river curled and wandered across the land.

Many people have heard the clamour that filled the room — Paul Engle forever calling out “Hualing, Hualing” from somewhere in the crowd, as well as Hualing’s thunderous laughter that could split mountains.

But has anyone heard Nieh Hualing cry in that house?

I heard it just once, a wailing so loud that it could shake the entire mountain to its core.

Mother was an Aquarian, born three days before Chinese New Year’s Eve. She was born straight into wartime, fleeing from place to place, and wherever she landed she learned to cook — grand delicacies, humble snacks, anything. When she reached Dalongdong, she learnt from the Tong’an (同安) women how to make rice cakes, sticky rice and a thick, savoury fish soup.

When she steamed buns, she made a hundred at a time; braised eggs, a hundred; glutinous rice dumplings, a hundred — all to be shared with the neighbours. After she emigrated to Vancouver, the garden burst with tomatoes, snow peas, zucchinis — and again, she shared them with the whole street. She didn’t know English, but everyone was filled with gratitude.

Embracing all with an unburdened heart

“Where am I from?” Hualing would ask me sometimes, a little dazed.

It is also difficult for me to say where Mother, Hualing or Benson are from.

Mother fled from place to place in the chaos of war. Perhaps she deeply understood that people need to eat regardless of where they are from, so she cooked to share with everyone.

Aquarians are fluid; they are much like a great river. When the river stops moving and the water silts up and becomes stagnant, doesn’t that mark the river’s death?

Laughter and tears, hugs, quarrels and fights, kindness and comfort, grudges and schemes — Hualing moved effortlessly among it all, utterly unburdened at heart.

Maybe a bottle is filled with a lot of water and wants to be poured out. Unless the bottle is empty, the water bearer’s energy is always being given away to all living creatures.

Hualing is the most typical Aquarian I have ever met. I’ve lost count of the number of people who have been to her little house on that hill in Iowa. It was always packed to the rafters with people from every corner of the globe, writers from all over. That world-renowned writing programme was, in truth, Hualing’s house. Laughter and tears, hugs, quarrels and fights, kindness and comfort, grudges and schemes — Hualing moved effortlessly among it all, utterly unburdened at heart.

I witnessed an Israeli writer and an Egyptian writer come to blows after a little squabble. A wine bottle smashed into a face, blood everywhere. Hualing just wrung out hot towels for each of them, not saying a word. Then suddenly, the two of them burst out laughing, and in the end clung to each other, sobbing their hearts out. Hualing cackled and pointed at them, “You two…”

Carrying our own grievances

We sometimes like to think of ourselves as “countries”, when we are really just humans. When Hualing looked at the Egyptian and Israeli writers, she just saw two people.

Politics tears people apart, pitting them against one another — fistfights, insults and bloodshed. Writers are no exception.

An Indonesian writer once yelled at me as well. I asked why Indonesia dislikes the Chinese, and he leapt to his feet in fury, demanding, “Do you know how the Chinese oppressed the locals?”

I didn’t know, so all I could see were my own grievances.

The Indonesian writer, still seething, threw me out. By November, Iowa was already bitterly cold. I walked along the river until midnight, kicking fallen leaves as a way to kick away my own unhappiness, and perhaps the Indonesians’ unhappiness as well.

When I reached the entrance of the Mayflower Apartments, I realised that I didn’t bring my keys. So I trudged back towards the river, the night growing colder, and it was clear I couldn’t possibly sleep outdoors. I called Hualing, “I forgot my keys.”

“Come on over,” she said, without a moment of hesitation.

I walked up the hill and Hualing had switched on the lights and opened the door. All of a sudden, the alarm blared, high-pitched and piercing, and she laughed out loud, “Damn it, I forgot to turn off the alarm.”

She did not probe me, just welcomed me in and led me upstairs. “Fancy a drink?”

We sat facing each other, sipping quietly, listening to the wind and the rustling leaves outside the window.

If there were a true writing programme, would it be like Hualing’s home, a space where writers, each carrying their own grievances, could also see the burdens others carry too?

Late into the night, after those who had quarrelled or fought had left, plates and cups were strewn all over the place. I helped Hualing clean up, bagging up sacks and sacks of rubbish.

Every week, I would go shopping with Hualing at the supermarket. She swept through the aisles like a west wind scattering leaves — beer, cheese, beef, ice cream — everything in quantities for 40 people. I pushed the trolley; food and paper plates piled up like a small mountain. And at the end of each gathering, there would be sacks and sacks of rubbish.

I looked at the pile, then at Hualing — past middle age yet brimming with life — I said, “You’re incredible.”

She burst out laughing, “Little rascal (小鬼), what do you know?”

She often calls me “little rascal”, perhaps laughing at my naivety and immaturity.

Hualing’s ‘Peach’ and ‘Mulberry’ sides

I loved her laughter. In the world’s clamour and lonely moments, that bold, unrestrained laughter of hers is like Aquarius’s rushing waters, endlessly flowing, giving life the courage to carry on.

After a big laugh, Hualing’s quietness was especially moving. She said, “At the end of the writing programme, a writer just threw me a newborn baby.”

“Wow! What did you do?”

“Find someone to adopt the baby, of course. What else!”

By the time I went, the writing programme was adjusted to four months. “Four months isn’t long enough for anyone to produce a baby,” I said.

Hualing burst out laughing again.

I loved to sit with Hualing after all the guests had gone, drinking some whiskey, listening quietly to the wind sweeping over the hill, the branches of big trees swaying and rubbing together, creaking softly. Raccoons and deer tiptoed nearby, peeking through the window.

She recounted the morning she saw the newspaper headline: her father, General Nieh, had been executed by the communists. Everyone rushed to hide the newspapers, afraid her mother would see.

She spoke of the massive Defence of Wuhan, how everyone fled the city and how she pushed against the crowds to get back inside, searching for her loved one.

She mentioned her pilot brother falling in battle.

We would sometimes talk about her book Mulberry and Peach (《桑青与桃红》) — those two utterly different yet coexisting qualities within one person, like the two states of an Aquarian: the moments when it is filled to the brim, and the moments when it is drained and silent.

She talked about “free China” being surrounded by the Taiwan Garrison Command; about how her palms were sweating but she still quietly urged her daughter to continue playing the piano.

When all the guests had left and the noise and loneliness had all passed, the thoughts of an Aquarian rippled gently like a quiet, trickling stream.

If you can hear it, you would understand an Aquarian’s roaring laughter and the profound loneliness beneath it.

We would sometimes talk about her book Mulberry and Peach (《桑青与桃红》) — those two utterly different yet coexisting qualities within one person, like the two states of an Aquarian: the moments when it is filled to the brim, and the moments when it is drained and silent.

Both extremes are Hualing. Most people only ever saw her “Peach” side; the “Mulberry” side tucked deep in her heart was far harder to glimpse.

And just how much can an Aquarian take on? Hualing had to deal with the everyday messes of writers from all over — eating, drinking, living, everything. And it went far beyond the business of someone abandoning an illegitimate child for her to sort out. There was a writer with depression, shut away in his room, and Hualing wanted me to leave food by his door every week. “Don’t disturb him,” she especially reminded me.

Perhaps it was her curiosity about human nature, or that Aquarian tolerance and breadth. To her, people are just people — everyone’s life is hard. I suppose that’s the core of the literature she believes in.

Perhaps she felt that good writing means either churning out children at random, shutting yourself away in a room, or getting bruised and bloodied at the slightest tiff.

She was never judgemental, and I have never heard her gossip about any writer behind their back. Perhaps it was her curiosity about human nature, or that Aquarian tolerance and breadth. To her, people are just people — everyone’s life is hard. I suppose that’s the core of the literature she believes in.

A lifeline to leave Taiwan

I went to Iowa in 1981. After I returned to Taiwan from France in 1976, I stirred up quite a bit of trouble without even realising it. The magazine I edited published work by Chen Yingzhen and other left-wing writers; the Taiwan Garrison Command summoned the publisher, and he went pale. I resigned. Then I went to help with the editorial work at China Tide (《夏潮》) magazine, and the university where I was teaching at suddenly dismissed me out of the blue. I felt a little defeated.

After a long period of authoritarian violence, the left was silenced, vanished without a trace. Can Taiwan still hold an ounce of care for the vulnerable and marginalised?

Perhaps I was too naive, leaving myself with no way out.

I wanted to return to France. My Aquarian close friend said coldly, “Did you come back for those people?”

“Those people” he mentioned are invisible. They have no name but lurk in every corner, informing, attacking, sending anonymous letters meant to ruin lives. Back then there was no such thing as “internet trolls”; we called all of them “party hacks” or “party thugs”.

And then I realised — I did not come back for “those people”. And it also clicked — “those people” will always exist. Invisible, nameless, borrowing the cloak of “justice”, chattering away while quietly pushing others to their downfall.

I wanted to leave for a bit and visit my family in Canada. Then I received a phone call from Hualing, “We’d like to invite you to Iowa.”

Aquarians never fail to throw me a lifeline whenever I am down.

The formal invitation and plane ticket came two days later. Hualing had always been efficient, never one for faffing about.

The itinerary had me connecting in San Francisco, then flying on to Chicago, transferring again to Cedar Rapids, and finally driving to Iowa. Looking down from the plane, all I could see was endless plains, all cornfields. Only then did I feel the true vastness of the US — not just the East and West Coasts I knew, but this great expanse of the Midwest.

Changing planes in Chicago, I suddenly caught sight of a striking figure in the bustling crowd.

“Ding Ling!” I screamed inwardly. An elderly woman, a head of fluffy white hair, dressed head to toe in grey. She stood there with her hands behind her back, like a sculpture came to life.

All the fashionable men and women around her immediately became background scenery, as if their only role was to be a mural complementing the sculpture. Colourful as it may be, your eyes remain glued to the sculpture.

Meeting icons

Chinese author Ding Ling’s The Sun Shines Over the Sanggan River was a banned book I secretly read in secondary school. When she first arrived in Yan’an and wrote about the peasants she saw, it was, in many ways, the shock of an urban intellectual female encountering the countryside for the first time.

Just like how she stood in the Chicago airport, staring at the stream of stylish urban men and women weaving past her.

I have also read Ding’s Miss Sophia’s Diary, which talks about a woman’s self-liberation — full of revolutionary fantasies, the voice of a fashionable, rebellious urban woman.

She was influenced by Chinese writer Qu Qiubai and fell in love with Chinese writer-poet Hu Yepin, and for a time their relationship was the talk of the town. Hu was executed and Ding was imprisoned, and Chinese philosopher Cai Yuanpei and others helped protect her. She eventually slipped north to Yan’an in secret.

She truly embarked on the path to revolution.

That year in Iowa, I got to know Ding and Chinese writer Xiao Jun — personalities I only knew from the “banned books” I read in my youth. Yet when they stood before me, they were simply ordinary people like everyone else.

In our life, how many turning points unfold without us even realising it? How is a female urban intellectual going to transform herself into a peasant?

Watching that sculpture-like figure from afar, what I was really reading was her history — and history itself was standing right before me.

That year in Iowa, I got to know Ding and Chinese writer Xiao Jun — personalities I only knew from the “banned books” I read in my youth. Yet when they stood before me, they were simply ordinary people like everyone else.

Ding slipped in the bathroom and her partner phoned me. I rushed to see her. The old lady was tough as ever, her walking stick still held perfectly straight. I went out to buy a non-slip mat for the bathtub and she was delighted, telling her partner, “I didn’t know such a thing existed.”

I accompanied Ding to New York, where she was interviewed by Susan Sontag. Ding talked about the famine in northern China, and her days being sent into exile. The Red Guards tormented her, giving her disabled chicken to raise. If she didn’t care for them well, she’d have to confess and be struggled against in front of the crowd. Sontag kept wiping her tears, and Ding comforted her: “But I raised them very well, you know — about 70%, 80% survival rate.”

Those who did not dance to the rulers’ tune

Iowa did not show me Ding Ling the icon or Ding Ling the writer, but a real, living person. Someone who, despite the circumstances, stubbornly and cheerfully lived on, sharing joy and suffering with the rest of us.

Do I really know Aquarians? Hualing knew full well that the vast resources behind the writing programme was funded by the US Information Agency (USIA). What sort of institution was the USIA? Would it invite so many writers from all over the world just to eat, drink and make merry?

To put it plainly, it was about recognising the greatness of America: visiting steel factories and touring the Smithsonian museums.

It was by far the most formidable state-funded “cognitive warfare” I had ever seen. And Hualing knew this inside out. She also understood the prevailing winds at the very top of American leadership and decision-making, and how to strike a balance between Taiwanese writers and Chinese writers.

That conversation came up because we were talking about how Ding Ling had been labelled as a rightist, and suffered so much because of it. She was also especially fond of Chen Yingzhen, “Taiwan’s leftist”, whom she had mobilised Chinese writers to rescue several times overseas.

One day, she said to me, “The adorable writers from Taiwan are all leftists. The adorable ones from the mainland are all rightists.”

That conversation came up because we were talking about how Ding Ling had been labelled as a rightist, and suffered so much because of it. She was also especially fond of Chen Yingzhen, “Taiwan’s leftist”, whom she had mobilised Chinese writers to rescue several times overseas.

I don’t think Hualing meant “left” or “right” in any strict ideological sense. Broadly speaking, she meant people with an independent character — those who refused to dance to the “rulers’” tune.

Under any regime, not cooperating with “rulers” seems to be the intellectuals’ biggest test. In one place they’d be labelled “left”, and in another labelled “right”.

They live by their own “cognition”, instead of treating them as the rulers’ tool for “warfare”.

Hualing escaped from the rule of one “Party” to the rule of another “Party”, and then came to America. She was a Democrat. Watching the noisy presidential campaigns on television, she said to me, “Isn’t Obama so handsome?”

She was still observing the people before her the way a novelist does.

This article was first published in Chinese on United Daily News as “水瓶座,懷念華苓(上)”.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)