Does Singapore still want to play an active role in the Chinese-speaking world?

Lee Huay Leng, editor-in-chief of SPH Chinese Media Group, looks back at Singapore's active role in the Chinese-speaking world and in the 1980s and 1990s, and whether it can - or wants to - resume such a role in a changing world.

In November last year, Zaobao ran an article by Dr Chan Cheow Thia of the Department of Chinese Studies at the National University of Singapore (NUS). Titled "Geography Lessons: Singapore, the 1990s and Wang Anyi's Root-Seeking Journey to the South" (大陆是漂浮的岛屿--新加坡、1990年代与王安忆南来寻根之旅的启发), it was a deep reflection on Singapore's current Chinese language environment through his research of Chinese writer Wang Anyi's visit to Singapore in the 1990s.*

Wang is a well-known writer from Shanghai. Her father Wang Xiaoping was born in Singapore in 1919, and was active in the theatre scene in Singapore and Malaya. In 1940, he left Nanyang (Southeast Asia) for China to join the war against Japan. He later stayed in China, and became a director with the Shanghai People's Art Theatre (上海人民艺术剧院). He was labelled a "rightist" during the Cultural Revolution, and returned to Southeast Asia after 50 years away.

Singapore's place in the Chinese-speaking world

China considered Wang Xiaoping a "returning overseas Chinese", while Chan suggests seeing him as a "diasporic Singaporean". Based on Wang Anyi's novels and her quest for her roots while in Singapore in 1991 for Lianhe Zaobao's fifth International Chinese Writers' Forum (国际华文文艺营), Chan placed Singapore back in the global Chinese-speaking world of that time. He said: "Looking back, Singapore held a relatively important cultural position in the Chinese-speaking world of the 1980s and 1990s. Amid its current marginal position, apart from going along with international trends, what mindset adjustments can Singapore consider if it wants to resume a more active role in the Chinese-speaking world?"

...but it seems we do not see Singapore having the ambition of wanting to play a role in the Chinese-speaking world.

Chan's question contains an "if". First, we have to assume that Singapore does want to resume a more active role in the Chinese-speaking world, before even talking about mindset adjustments. This is a major issue that calls for perspective and confidence - it is not just about Chinese pedagogy or culture, but is closely tied to the domestic and external environment, and geopolitical changes.

Compared to the 1980s and 1990s, there has been an increase in Chinese culture-related organisations of scale in Singapore - there are more Chinese faculties and research centres than back then. The government also strongly supports organisations like the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre, but it seems we do not see Singapore having the ambition of wanting to play a role in the Chinese-speaking world.

We see more of Singapore maintaining the status quo, where Chinese cultural organisations largely organise activities catering to the standards and preferences of young Singaporeans, and focus on attracting their attention in newfangled ways. At the same time, they also emphasise and uphold the uniqueness of Singapore's own Chinese culture, and seldom discuss cultural plans and visions.

Even with the current inflow of funds and people from all over the world and the foreign media focus, what Singapore wants is to strengthen its position as an economic, financial and R&D centre. Cultural development is done to attract and retain talent and to meet their cultural needs as far as possible.

Another more important objective in focusing on culture is to strengthen Singaporeans' national identity. Taking the initiative in promoting the meeting of minds to gather and enrich diverse cultural assets is not even in the plan, much less wanting to play a key role in the Chinese-speaking world.

Culture as its own reward

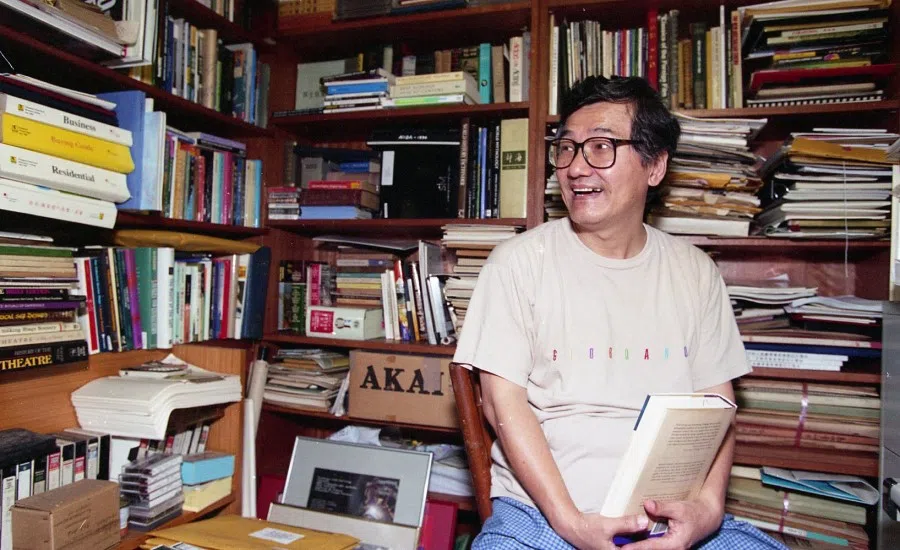

Can we have such lofty ambitions? What efforts can the people contribute? Chan's article mentioned several key cultural activities in Singapore during the 1980s and 1990s, including the Asian and international university debates organised by the then Singapore Broadcasting Corporation, and which were popular among Chinese universities, as well as the theatre camps planned by the late dramatist Kuo Pao Kun.

Then, China's intellectual circles were open and vibrant - they were at their most influential when they did not intentionally try to exert an influence.

Kuo was born in a village in Hebei and came to Singapore at the age of ten, and later dedicated his life to driving the development of cultural diversity. In late 1987, he gathered the popular Chinese-language dramatists of the time, including Performance Workshop artistic director Stan Lai from Taiwan, Absolute Signal (《绝对信号》) playwright Gao Xingjian, Shanghai Theatre Academy professor Yu Qiuyu, and Zuni Icosahedron artistic director Danny Yung from Hong Kong, allowing them to meet in Singapore and bounce ideas off one another, and widen the horizons of local theatre practitioners.

That was an era where people in the Chinese-speaking world treated culture with sincerity and respect; a time when culture was not overly commodified and political wrestling was much less prominent. I was a beneficiary of that era, and could list many more activities such as these. I was still a secondary school student then and voluntarily registered for these activities because of my interest in them.

At that time, we felt the infinite charm of Chinese culture although the Chinese economy was not that strong. We were keenly aware of the distance between us standing on the periphery and those at the centre of Chinese culture; at the same time, we experienced a Chinese culture that was big-hearted and unbothered by petty trifles.

Then, China's intellectual circles were open and vibrant - they were at their most influential when they did not intentionally try to exert an influence. Those were the days when the mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan each had different political systems and environments and expressed culture in unique and different ways. But they acknowledged the fact that they came from the same origin, and gave one another space while treating one another equally and with respect, making each of them more approachable to the outside world.

China pushing Chinese culture onto the global stage

Now, China is a strong country boasting not only a massive market, but also growing economic, technological and military power. The US is doing everything it can to stop its rise, making China more aware of the need to strengthen its propaganda efforts.

Confronting Western-led international discourse, China must "help foreign audiences understand that what the party pursues is the well-being of Chinese people" and "help foreigners know how the CPC can get things done, why Marxism works and why socialism with Chinese characteristics is good".

People-to-people exchanges between China and other countries must be combined with pushing Chinese culture out onto the global stage and with the aims of the Communist Party of China's united front to "unite Chinese people at home and abroad to achieve national rejuvenation".

There have been more considerations about "political correctness" in the cultural exchanges between the mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan...

The current international situation and public opinion environment are very different from the 1980s and 1990s. There have been more considerations about "political correctness" in the cultural exchanges between the mainland, Hong Kong and Taiwan, while the cultural space where free and equal exchanges used to exist in the Chinese-speaking world is gradually changing as well.

Singapore is a small country and has always been more sensitive to sovereignty issues than other countries. Coupled with the fact that its racial structure is susceptible to provocations, Singapore is still slowly building a foundation of self-confidence as a country. At this time, not only will the Singapore government not choose sides in terms of geopolitics, but it will also be extra careful in terms of its cultural identity to avoid being labelled as leaning towards a certain side.

Bigger obstacles to play a bigger role

In the past, Singaporean sociologist Eddie Kuo further extended American scholar Tu Wei-ming's "Cultural China" (文化中国) concept to the concept of "Cultural Chinese" (文化中华), which in fact encompasses Singapore. This is why the Singapore University of Social Sciences and Lianhe Zaobao jointly organise the Cultural China Public Lecture (新跃文化中华讲座) every year, which invites speakers from various regions to speak on various cultural topics.

In the past, Singapore, which was situated in the periphery, was very active in these events. Now that the times have changed, Singapore is faced with bigger challenges if it wants to play an active role in the Chinese-speaking world.

... although the Chinese language is clearly on the decline, there remains a significant number of Chinese-speaking cultural heirs all across society.

We do not know how long this can be sustained. But an objective reality in Singapore is this: after the country's language policy was changed, although the Chinese language is clearly on the decline, there remains a significant number of Chinese-speaking cultural heirs all across society.

Worried about the disappearance of their matriarchal culture, they emotionally and instinctively defend and promote culture, some as advocates and others as practitioners. But such motivation and passion has weakened in the new era of pragmatism and rationality. Once such a cultural undertone and perspective is lost, the Chinese-speaking world in Singapore may face great uncertainty, but by that time, it may be a whole new world altogether.

*Dr Chan's article in Zaobao was an abridged version of his talk of the same name on 29 October 2022, at the Lien Fung's Colloquium at Singapore Management University. The video of the talk can be found here.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as "新加坡还想在华语世界扮演积极角色吗?".

Related: Challenges of Singapore's Chinese community amid competing influences: Lessons from an old bookstore | True gems: Singapore's pioneers of the arts deserve more credit | How the 'tree' of Chinese writing united dialects, culture and people through the millennia | Trees in a forest: Becoming Chinese Singaporean in multicultural Singapore