True gems: Singapore's pioneers of the arts deserve more credit

I believe there are still those among us in Singapore who think that our Chinese arts and heritage is a pale shadow or mere derivative of the larger cultural entity of China perhaps due to our short history and relative small size as an immigrant society.

This is unfortunate because it reflects not only a needless sense of inadequacy but also a serious lack of understanding about our own strength and value.

Having spent many years writing about some aspects of the Chinese community in Singapore, I will say that a good number of our artists of Chinese descent have successfully forged their own identity with a strong and unique character, and have brilliantly distinguished themselves from their peers in China.

Here I would like to cite two examples just to show how far Singapore has gone in striking out on its own by taking advantage of the pluralistic foundation built on our own multicultural traditions.

Wu Guanzhong and Singapore's pioneer artists had some things in common

A recent talk Wu Guanzhong and Singapore given by a curator from the National Gallery Singapore (NGS) reminded me of an article of the same title I wrote for the exhibition marking the artist's donation of his paintings to Singapore in 2008, as well as my essay for the Wu Guanzhong exhibition "Beauty Beyond Form" that inaugurated the NGS in 2015.

Somehow, the talk did not touch on Wu's relationship with Singapore that might have led to his very generous donation of paintings as I tried to do in my 2015 essay for the exhibition catalogue "Closer Than Imagined: Wu Guanzhong and Singapore".

Though Wu himself said he felt emotionally close to Singapore... he didn't elaborate on how specifically the relationship was close.

Though Wu himself said he felt emotionally close to Singapore as if that was why his gift to us was more generous than what he gave to Beijing, Shanghai, Hangzhou and Hong Kong, he didn't elaborate on how specifically the relationship was close. For instance, he never named any Singapore artists he might have met or art institutions such as the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts that he should have visited.

Based on what we know, it is actually not quite clear to what extent Wu, one of China's greatest artists of the modern era, was engaged with fellow artists and the art scene on his several visits to Singapore.

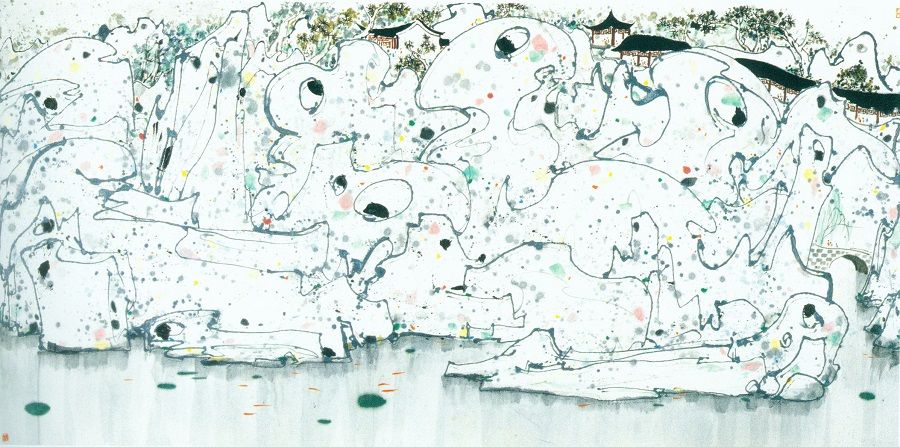

In my essay, I venture a comparison between Wu's art and those of Singapore pioneer artists such as Cheong Soo Pieng, Chen Wen Hsi and others, who produced equally outstanding paintings in both oil and ink, and suggest that Wu would have found himself closer to them artistically.

Wu called his own painter's practice "an amphibious journey" where he would creatively switch between the two mediums comfortably. This is how I see the practice of many Chinese-educated artists who paint in the same "amphibious" way in Singapore. In this sense, I imagine Wu would have found kindred spirits here if he had had the opportunity to learn more about Singapore artists.

This is especially so in the case of Chen Wen Hsi, Liu Kang, Chen Chong Swee, Georgette Chen and Cheong Soo Pieng, whose excellent paintings are among the best representative works of the modern art movement in Singapore as well as the Chinese-speaking world.

In his famous line on what he hoped to achieve with his approach to painting, Wu set out to "indigenise oil painting and modernise Chinese painting" (油画民族化、中国画现代化). In fact, Wu began his career painting mainly in oil before he busied himself with ink painting from the mid-1970s onwards. He would have been greatly surprised to find his Singapore counterparts well advanced along the same journey right from the start of their careers going back to the 1950s or even earlier.

Singapore's pioneer artists, who arrived from China around mid 20th century as full-fledged practitioners, actually ventured further in their adopted country - they showed in their work in oil and ink how they sought to reflect a sense of place and situate their aesthetics in a wider context of Southeast Asia. This is especially so in the case of Chen Wen Hsi, Liu Kang, Chen Chong Swee, Georgette Chen and Cheong Soo Pieng, whose excellent paintings are among the best representative works of the modern art movement in Singapore as well as the Chinese-speaking world.

Theatre great Kuo Pao Kun, a trailblazer ahead of his time

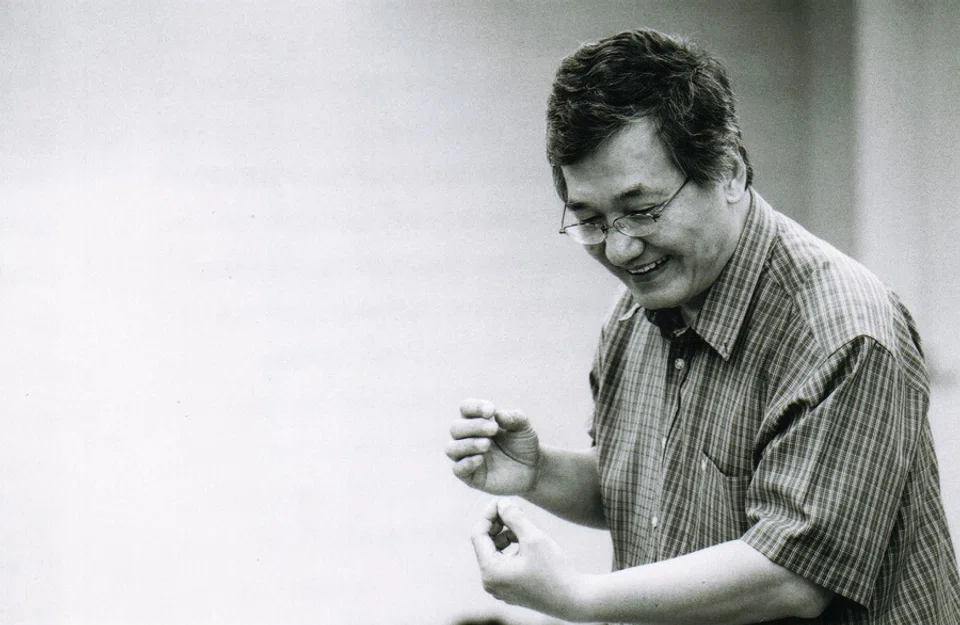

My second example was prompted by a talk on Singapore theatre artist Kuo Pao Kun I myself gave at the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre recently. In my presentation, I spoke about the great significance of foreign plays that Kuo translated and staged in Chinese. The talk was based on an essay I wrote for The Complete Works of Kuo Pao Kun for which I was editor of the volume on plays that Kuo had translated.

Besides his own original plays, Kuo Pao Kun (1939-2002), Singapore's foremost playwright and public intellectual, is known for his pioneering work in introducing some of the world's best theatre well ahead of other dramatists in the entire Sinophone world.

What is particularly striking is the way Kuo chose what he thought was good instead of relying on translations from China.

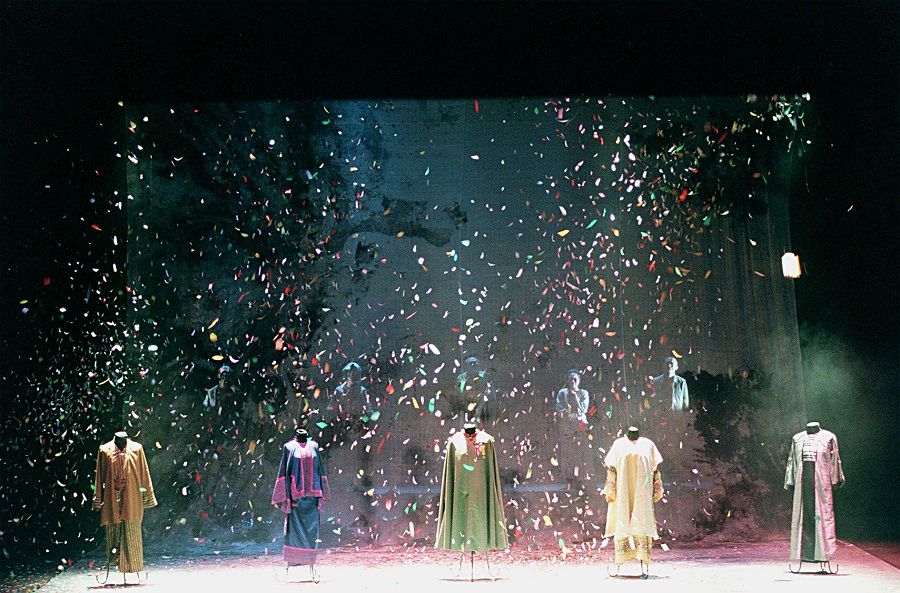

Between 1965 and 1987, Kuo translated seven plays from Australia, Germany, South Africa, the US, Switzerland and Malaysia, and staged them in Chinese. He showed remarkable vision and foresight in his choice as every one he picked turned out to be a historic classic performed in Chinese for the very first time.

What is particularly striking is the way Kuo chose what he thought was good instead of relying on translations from China.

In 1967 Kuo translated black American playwright Lorraine Hansburry's play, A Raisin in the Sun, and directed its performance in Chinese. The play, telling of how a black family in South Chicago deals with discrimination and racism, became an instant critical success when it debuted on Broadway in 1959 with an all-black cast. When its run ended in 1960, it had done a total of 530 performances.

Recently, I was amused to read online reports from China claiming that the Beijing People's Art Theatre's production of the play in 2020 was the first-ever in Chinese without realising it had already been done in Singapore in 1967 - more than half a century earlier.

With his translation of Bertolt Brecht's Caucasian Chalk Circle, which his company The Theatre Practice performed in Singapore under his direction in 1968, he presented the German playwright's celebrated play in Chinese for the first time. Though Brecht was first introduced to China in the late 1950s, this important play was not translated and performed until well into the 1970s and 1980s in mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong.

Going where others have not gone before

Besides, Kuo also actively championed Brecht's work by helping the Goethe Institut organise a three-week East-West conference in Singapore to discuss in English and Mandarin his legacy among dramatists from Germany, China, Hong Kong and Malaysia in 1989.

Kuo's passionate advocacy did not stop at Brecht but also included Athol Fugard, another giant in world theatre. He translated into Chinese The Island, a powerful play about apartheid through the experience of two political prisoners on Robben Island by the South African playwright and staged it in 1985. Meanwhile, Kuo had recommended Fugard's work to organisers of the 1986 Singapore Arts Festivals who brought in his Master Harold and the Boys performed by a South African company.

Never translated in China before, The Island was staged in English by an international cast under a Chinese director with a rather lukewarm reception in Shanghai in 2015 - three decades after it had triumphed on the Singapore stage as one of the most memorable performances of Chinese-language theatre.

In addition, I have not yet seen or heard of any meaningful activities lined up on the scene for 2022 dedicated to the memory of Kuo Pao Kun - this year being the 20th anniversary of his passing.

In the late 1970s, he taught himself Malay during his four-and-a-half-year detention under the Internal Security Act and became good enough to translate Kala Dewata's Atap Genting Atap Rembia (tiled roof, thatched roof), a Malaysian play about rural-urban conflict, which he staged in Chinese in 1982.

As I review the facts of these two examples, I feel that there is a need for more to be done to recognise the importance of our own artists. A talk about Wu Guanzhong and Singapore, for instance, should have discussed the implications of his engagement with Singapore artists and the art scene as well as his artistic visions vis-a-vis those of our pioneer artists.

In addition, I have not yet seen or heard of any meaningful activities lined up on the scene for 2022 dedicated to the memory of Kuo Pao Kun - this year being the 20th anniversary of his passing.

Come on, Singapore!