[Big read] Deep-sea mining: Is the ocean floor the next battleground?

Amid the race for minerals, one frontier remains relatively untapped: the ocean bed. But as countries ramp up deep-sea mining, the US’s move to bypass global governance institutions risks undermining ocean stability, sparking disputes, unregulated exploitation and environmental harm. Lianhe Zaobao associate foreign editor Poh Hwee Hoon finds out more.

“The deep sea cannot become the wild west.”

On 9 June, at the UN Oceans Conference in Nice, UN secretary-general Antonio Guterres urged countries to approach deep-sea mining with caution. Along with other leaders, he warned against unilateral seabed mining activities and called for strict regulations on such operations.

The criticism was aimed at the executive order on deep-sea mining issued by US President Donald Trump on 24 April, which invoked the obscure Deep Seabed Hard Minerals Resource Act of 1980. The order directed the administration to accelerate deep-sea mining efforts in both domestic and international waters. This move has drawn the attention of the international community, not only due to fears that commercial exploitation could damage fragile seabed ecosystems, but also because the US action represents a circumvention of international oversight mechanisms.

US bypassing global ocean governance system

According to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), countries have the right to approve deep-sea mining activities within its territorial waters. However, in international waters, it is the International Seabed Authority (ISA) that is in charge of approving exploration and development.

The US Congress has not ratified UNCLOS, and the US is not a member of the ISA.

To date, the ISA has issued 31 mineral exploration licenses, each valid for 15 years, but it has not yet approved any commercial mining operations, as the regulations governing such activities are still under review. The ISA comprises 167 member states and the European Union. Due to concerns among some members that commercial-scale seabed mining could harm the environment, negotiations over the relevant regulations have gone on for years with no conclusion.

The US Congress has not ratified UNCLOS, and the US is not a member of the ISA. As such, it is excluded from most of the ISA’s procedures and cannot apply for exploration licenses in international waters.

The Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act enables the US to retain control over its own licensing. This law provides a legal basis for US citizens to explore and mine mineral resources on the US continental shelf and beyond, and authorises the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to issue both exploration and commercial mining licenses for deep-sea activities.

Trump’s executive order effectively pushes federal agencies to actively pursue a strategy of bypassing the ISA and proceeding with direct mining operations in international waters. The ISA has criticised the US’s unilateral actions, warning that they set a dangerous precedent and could undermine the stability of the entire global ocean governance system.

Responding to an inquiry from Lianhe Zaobao, a Chinese expert who requested anonymity stated that the numerous current disputes among countries over deep-sea mining are being addressed within the framework of maritime law, using legitimate political and legal channels. However, Trump’s attempt to bypass institutional constraints and force through seabed mining is bound to disrupt the already fragile balance, increasing the risks of negative competition, unregulated exploitation, and environmental degradation.

Seabed mineral deposits could meet global demand for a century

Deep-sea mining refers to the extraction of solid mineral resources from the seabed at depths exceeding 200 metres. The global ocean floor is rich in minerals and metals such as gold, silver, copper, cobalt and nickel, with estimated reserves potentially sufficient to meet global demand for decades, if not centuries.

Metals like copper, cobalt, and nickel are essential raw materials for clean energy technologies such as electric vehicle batteries, solar panels, and wind turbines. As countries strive to reduce their reliance on fossil fuels and cut carbon emissions, global demand for these minerals has surged. The International Energy Agency predicts that by 2040, global demand for these metals will double.

Mining, already considered highly destructive on land, may cause even greater damage on the seafloor, though the full extent remains unknown.

The US government estimates that within US waters alone, there are over 1 billion metric tons of mineral-rich deep-sea nodules. If extracted, they could inject hundreds of billions of dollars into the US economy and create 100,000 jobs within a decade.

Although deep-sea mining poses potentially irreversible harm to marine life and ecosystems, and continues to face technological and regulatory hurdles, many countries are forging ahead in seeking new sources of critical minerals beyond terrestrial mining, enticed by the vast economic potential. Besides China and the US, nations such as Russia, India, Japan, South Korea, and Norway are also exploring mineral deposits beneath the ocean floor.

36 countries in support of halting deep-sea mining

However, humanity’s understanding of the ocean remains limited. To date, only a small portion of the world’s oceans has been thoroughly mapped — estimates range from just 5% to 26% of total ocean area. Mining, already considered highly destructive on land, may cause even greater damage on the seafloor, though the full extent remains unknown.

Cynthia Mehboob, a hybrid threats analyst at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, warned in an interview with Lianhe Zaobao that if deep-sea mining is allowed to proceed at scale, it will pose serious threats to existing underwater infrastructures, particularly submarine cables and pipelines that support global internet traffic and energy transmission, by physically disrupting cable routes. Consequently, tensions between states that depend on uninterrupted connectivity and those prioritising seabed resource extraction will escalate.

As of 9 June, 36 countries have expressed support to halt deep-sea mining, calling for more research into deep-sea ecosystems to ensure that mining activities will not cause irreversible environmental damage.

However, the unilateral actions of the US could undermine these efforts. In fact, following Trump’s executive order, companies unwilling to wait for the ISA to finalise deep-sea mining regulations — such as Canadian firm The Metals Company — have begun applying directly to the US for commercial mining licenses.

But there are growing concerns that it could encourage other countries to follow America’s lead, bypassing the ISA and issuing their own licenses.

Such exploitation of loopholes may indirectly pressure ISA member states to end the prolonged deadlock and accelerate consensus on seabed mining regulations. But there are growing concerns that it could encourage other countries to follow America’s lead, bypassing the ISA and issuing their own licenses.

In an article “Deep-Sea Rivalry — Chinese and American Mining Strategies and the Future of Ocean Governance” (《深海博弈:中美采矿战略与未来海洋治理》), Hong Nong, executive director of the Institute for China-America Studies (ICAS), wrote that even though China continues to be a staunch supporter of the ISA, if more countries decide to act unilaterally, China would be under pressure to reconsider its strategy.

At that point, nations may come to believe they have the right to claim the seabed resources of the high seas as their own, significantly increasing geopolitical risks. The prospect of conflicts over seabed resources may then no longer be a distant concern.

Deep-sea mining to aid the US against China?

The first line of the executive order signed by Trump in April states clearly: “The United States has a core national security and economic interest in maintaining leadership in deep sea science and technology and seabed mineral resources.”

The document says: “The United States faces unprecedented economic and national security challenges in securing reliable supplies of critical minerals independent of foreign adversary control. Vast offshore seabed areas hold critical minerals and energy resources. These resources are key to strengthening our economy, securing our energy future, and reducing dependence on foreign suppliers for critical minerals. of foreign adversary control”. The document also called for “strengthening partnerships with allies and industry to counter China’s growing influence over seabed mineral resources”.

At present, China controls about 95% of the global supply of rare earth metals and produces three-quarters of the world’s lithium-ion batteries. If deep-sea mining begins in earnest, China is expected to expand its dominance over emerging industries such as clean energy, potentially gaining a powerful new advantage in the intensifying US-China rivalry.

China currently holds five seabed exploration licenses issued by the ISA, the most held by any country.

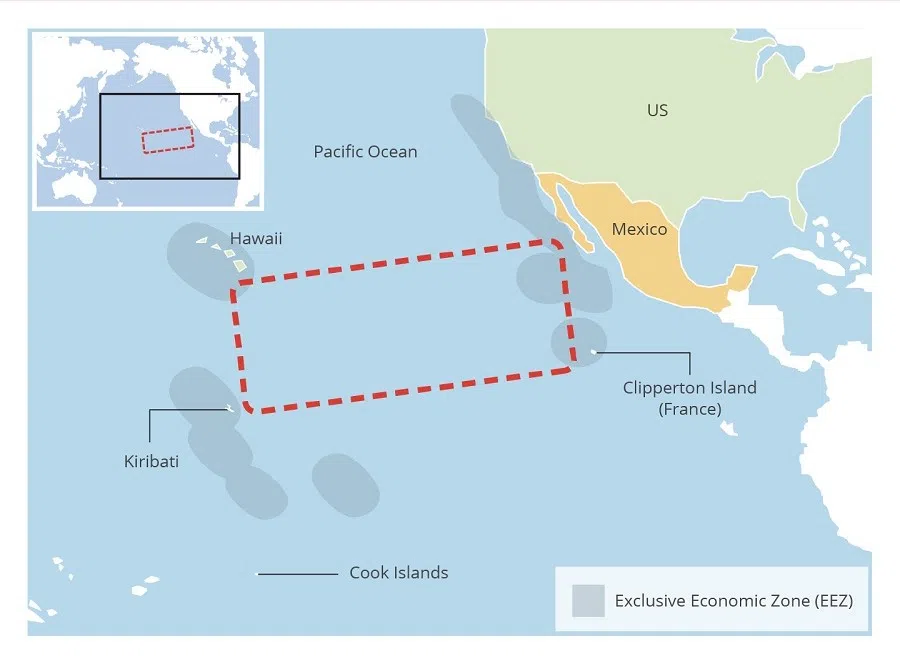

Unlike the US’s unilateral approach, China is advancing its deep-sea exploration within the framework of the ISA and partnering with island nations such as the Cook Islands and Kiribati for joint deep-sea exploration and mining projects.

China currently holds five seabed exploration licenses issued by the ISA, the most held by any country. Three of these licenses cover areas in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), located in the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Hawaii.

China is also actively building influence within the ISA’s rule-making bodies, helping to shape global mining regulations in a way that embeds its technological, legal, and operational advantages into the future structure of seabed governance.

This progress is increasingly viewed as a strategic threat. In recent years, Western countries have begun to link deep-sea mining to national security concerns.

In an article published in April by American thinktank Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), Gracelin Baskaran, director of its Critical Minerals Security Programme and Meredith Schwartz, a research associate in the same programme, wrote that China has been developing dual-use technologies with both commercial mining and potential military applications, including autonomous underwater vehicles.

“If China were to send vessels and remotely-operated vehicles into the CCZ, not far from Hawaii, under the guise of deep-sea mining activities, it could be challenging to tell whether its activities were purely commercial.”

Deep-sea mining not a silver bullet

However, Mehboob criticised the redefinition of deep-sea minerals as a geopolitical necessity during her interview. She argued that mining companies, facing financial pressure and declining investor confidence, are actively marketing deep-sea mining as a cure-all solution for the West to reduce its dependence on China’s critical mineral supply chains.

Mehboob said this framing has gained traction in policy circles, especially in the US, where seabed extraction is now being pitched as a national security imperative. “But this narrative obscures the key reality that western reliance on Chinese critical minerals stems less from a scarcity of minerals and more from China’s dominance in refining and processing capacity. Deep-sea mining does not resolve this bottleneck but merely shifts the problem downstream.”

For example, China is estimated to mine less than 5% of the world’s nickel and cobalt ore, yet it controls 75% of the global processing and supply chain for both metals.

Hong Nong recommends that the US and China work together on deep-sea mining to pursue sustainable development.

Rather than negative competition under the sea, Hong Nong recommends that the US and China work together on deep-sea mining to pursue sustainable development. She believes that cooperation could take the form of building a deep-sea technology alliance under the leadership of the ISA — an alliance that would bring together researchers, industry stakeholders, and the public to minimise environmental damage and ensure mining activities are transparent and well-regulated. She also proposes the creation of an open data platform to share scientific findings and monitoring results, as well as exploring new agreements that would direct a portion of deep-sea mining revenues toward ocean conservation efforts.

Hong said: “Deep-sea mining goes beyond competing for resources, it is also a test of how international society overcomes strategic asymmetry through legal pluralism and cooperation to govern global commons. The choices made by the US and China will not only determine the future of this ‘last wild frontier’ of the oceans, but will also have a profound impact on global environmental governance.”

Mineral deposits vs localised extinctions of species

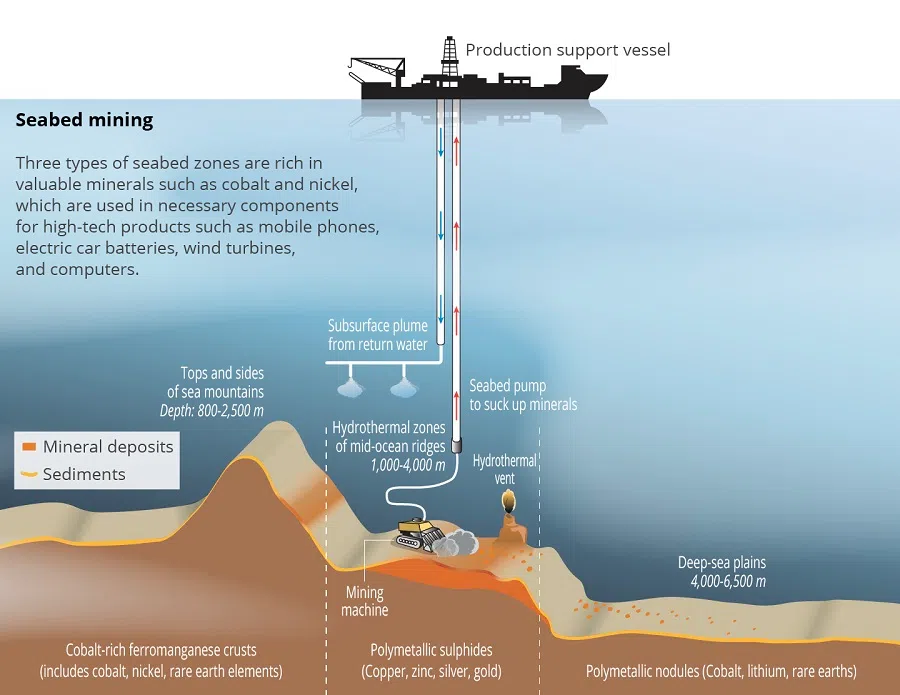

The seabed holds three main types of metal-rich mineral deposits, with the potential extractable resources estimated to be worth several trillion US dollars.

The most sought-after of these are polymetallic nodules — rock formations about the size of potatoes, formed over millions of years as minerals slowly precipitate around fragments such as shark teeth or fish ear bones. These nodules are rich in copper, nickel, cobalt, and manganese, along with trace amounts of rare earth elements. They are typically found on deep-sea plains at depths below 4,000 metres. The most accessible area for potential development is the CCZ in the Pacific Ocean, which spans 4.5 million square kilometres and is estimated to contain 21.1 billion tons of nodules.

... all of which can have severe negative impacts on habitats and biodiversity far beyond the actual mining sites. In some cases, this could even lead to localised extinctions of species.

Polymetallic sulphides, on the other hand, are found near deep-sea hydrothermal vents, where seawater interacts with materials from deep within the Earth’s crust. These reactions create dense deposits of sulphides rich in copper, zinc, lead, silver, and gold. Such mineral beds are located along mid-ocean ridges and submarine volcanoes, particularly in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, at depths ranging from 1,000 to 4,000 metres.

The third type of deposit is the cobalt-rich ferromanganese crust, which forms through the accumulation of metals from seawater and coats the surfaces of seamounts. These crusts are found at depths ranging from 800 to 2,500 metres, and a promising area has already been identified in the northwestern Pacific.

According to the environmental NGO Greenpeace, deep-sea mining is inherently destructive because it involves extracting resources from the very substrates to which deep-sea organisms attach. The process also introduces pollution and physical disturbances such as noise, vibration, and artificial light, all of which can have severe negative impacts on habitats and biodiversity far beyond the actual mining sites. In some cases, this could even lead to localised extinctions of species.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “深海采矿辟新战场 肆意挖宝生态难保”.