[Big read] From major port to cruise terminal: How Malaysia’s Melaka Gateway fell short

When Malaysia’s Melaka Gateway was launched in 2014, it was touted as a rival to Singapore’s port. It has not lived up to expectations, but will recent renewed interest make a difference? Lianhe Zaobao correspondent Seoow Juin Yee finds out more.

“Plans for Melaka Gateway have cooled. At first they said it was a mega project, and then construction stopped; it’s been quite a few years. If you ask Melakans, we all feel that it’s been abandoned.”

Wong Meng Xi runs a provision shop in Pulau Melaka just off the coast of downtown Melaka, next to Pulau Melaka East 1 (PME1), the planned site of Melaka Gateway which was to include tourism, entertainment, fashion, and retail businesses.

But no progress has been made on Melaka Gateway for years, and the whole of PME1 has turned into a ghost town. Wong’s shop is one of the very few businesses still running.

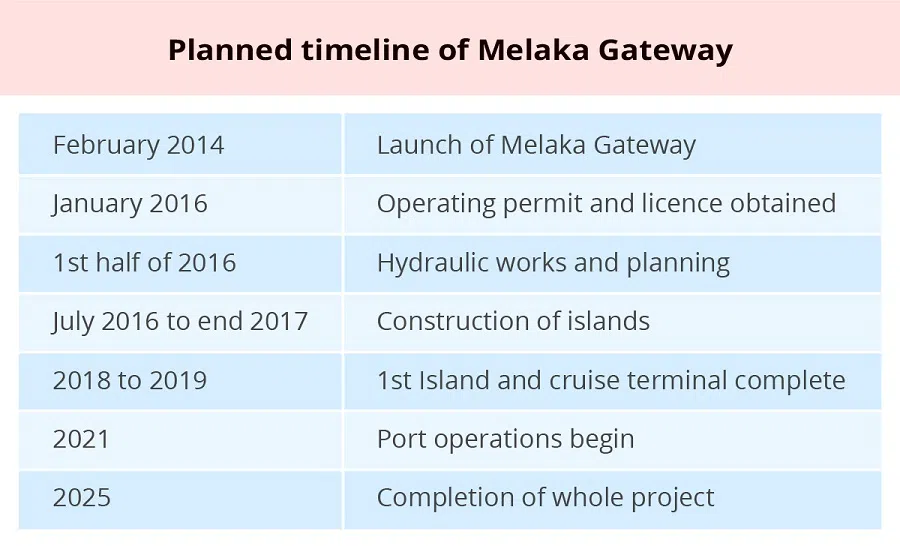

Slated for completion in 2025

Wong told Lianhe Zaobao when construction on Melaka Gateway was still under way, some construction workers would still come to his provision shop, but after construction halted, his store grew quiet.

“It can’t be helped, because development has stopped… mainly because of political instability, the Melaka government has already been changed three times, so the mega projects had to be approved again.”

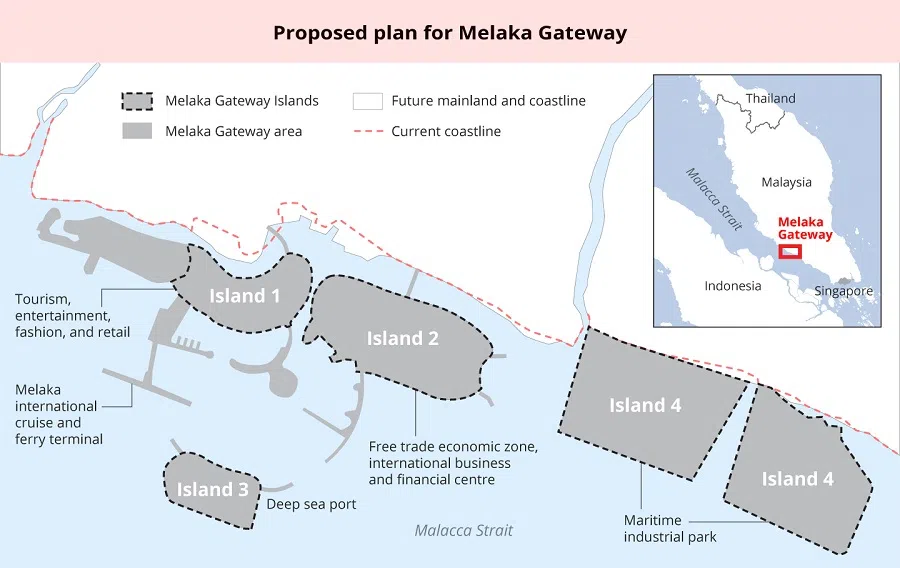

Development for Melaka Gateway, which was to be built on three man-made islands and one natural island joined together through land reclamation, began in 2024. According to the original blueprint, the RM43 billion (US$9.9 billion) project would draw 2.5 million visitors annually, create 45,000 jobs and generate RM1.19 trillion worth of economic benefits.

The entire Melaka Gateway project was slated for completion in 2025. However, when the Lianhe Zaobao team visited the Melaka in mid-August this year, we discovered that the entrance to the development was sealed, and PME1 — the only island that has been built — remained a wasteland with no sign of construction.

Some media, experts, and analysts painted the project as a replacement for Singapore as the largest port in the region, which would also allow China to carry out surveillance of the Strait of Malacca...

Fears of Melaka Gateway cannibalising other ports

A large integrated entertainment resort development on Pulau Melaka, which adjoins PME1, lies abandoned, with hundreds of empty shop spaces on its periphery, alongside the uncompleted Arab City development. The atmosphere was somewhat apocalyptic.

Melaka Gateway is one of several large scale infrastructure projects that are joint ventures between Malaysia and Chinese investors; it was listed as one of the developments under China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and had support from both the Malaysian and Chinese governments.

In 2015 when the late former Chinese Premier Le Keqiang visited Malaysia, he went to the planned site for Melaka Gateway. Malaysia’s former Prime Minister Najib Razak also declared strong support for the project and included it in the nation’s plans for economic transformation.

The development of Melaka Gateway was spearheaded by KAJ Development (KAJD), in cooperation with the Melaka state investment arm Chief Minister Incorporated, China’s state-owned PowerChina, and four other provincial state-owned enterprises from China making up the rest of the investment coalition.

The Melaka Gateway plan was launched to much fanfare in February 2014, at a time when China’s Belt and Road Initiative was gaining momentum, drawing ample international attention. Some media, experts, and analysts painted the project as a replacement for Singapore as the largest port in the region, which would also allow China to carry out surveillance of the Strait of Malacca — a strategic maritime route that played a vital role in China’s energy supply chain.

Melaka Gateway would cannibalise the three largest national ports in Malaysia, harming the interests of the operators, investors and other stakeholders behind them.

But such an argument would mean Melaka Gateway would first replace Port Klang, Penang Port, and Port of Tanjung Pelepas, which together make up 70% of Malaysia’s total port throughput. In other words, Melaka Gateway would cannibalise the three largest national ports in Malaysia, harming the interests of the operators, investors and other stakeholders behind them.

A report authored in 2020 by Francis Hutchinson, senior fellow and coordinator of the Malaysia Studies Programme at ISEAS- Yusof Ishak Institute (ISEAS), and Tham Siew Yean, a visiting senior fellow at the institute, said that Melaka Gateway was not classed as a national infrastructure project in Malaysia; and the addition of a mega port would eat into the market share of Port Klang and Tanjung Pelepas, which could be the key reason the project failed to attract key Malaysian investors.

Because of this, despite apparent support from the Najib government, the project has never received federal funding; sovereign investment fund Khazanah, government-linked funds such as the Employees Provident Fund (EPF), national infrastructure investors such as UEM and Gamuda, major port operators such as MMC and Westport Holdings, all kept their distance from Melaka Gateway.

In an analysis published in 2019, Hutchinson observed that while KAJD and Chief Minister Incorporated had a good understanding of the local business environment, they might not have a strong network of relations at the federal level, which would have affected their ability to borrow from banks and raise funds in the financial market.

... the scale was significantly reduced, and only an international cruise terminal will now be built.

Revival with the support of the Johor royal family

Melaka Gateway has not had a smooth run. In 2018, when payment became a problem for the project, and land reclamation works had to be put on hold, the Ministry of Transportation revoked its operating license. After repeated delays in construction, the Melaka government also withdrew the project’s permit for land reclamation, and the project was halted.

KAJD took legal action against the transport minister, the state government and the port authorities, and a settlement between the different parties was reached in 2022.

In September last year, KAJD announced that construction on Melaka Gateway would restart with the support of the federal and state government, and funding from new investors and new stakeholders under a new leadership. But the scale was significantly reduced, and only an international cruise terminal will now be built.

In an article published on 15 February 2024 on Fulcrum, the website of ISEAS, Tham Siew Yean observed that the international cruise terminal was part of the original plans for Melaka Gateway. Now that the entire development has been reduced to just one component, funding requirements will also be cut from RM 43 billion to around RM 682 million, just 1/63 of the original scale.

The ownership of KAJD has also undergone some changes, most noteworthy being the addition of the Johor Royal Family.

As for Chinese investment in the coalition, only SinoHydro is currently involved in the land reclamation works. The company is a subsidiary of Power Construction Corporation of China.

News website Malaysiakini, citing data from the Companies Commission of Malaysia (SSM), reported in March last year that Sultan Ibrahim of Johor had injected RM6 million into KAJD for a 30% stake to become the second largest shareholder.

The Sultan’s close friend, Malaysian tycoon Daing A Malek also invested RM2 million for a 10% stake, and has also been appointed chairman of the executive board in the company. There was speculation that with the Johor royal family entering the fray, new life would be injected into the Melaka Gateway project. Sultan Ibrahim was crowned the King of Malaysia in February this year.

As for Chinese investment in the coalition, only SinoHydro is currently involved in the land reclamation works. The company is a subsidiary of Power Construction Corporation of China.

The four provincial state-owned enterprises who were part of the initial plans for the Melaka Gateway project, Shenzhen Yantian Port Group, Shandong Rizhao Port Group, Guangzhou Port Group and Guangdong Provincial Communications Group, were originally entitled to stakes on PME1, 2, 3 and 4. Current arrangements are unknown.

Attempts by Lianhe Zaobao to contact KAJD failed to get any response.

Hutchinson and Tham concluded in their 2020 report that two main obstacles prevented Melaka Gateway from realising its original ambitions. One, the local partners selected by the Chinese investors were too small to deliver the hoped-for results. Two, the project posed a direct challenge to the interests of the national economic elite, including the wealthiest Bumiputera and influential government-linked corporations.

Experts: unrealistic for Melaka Gateway to replace Singapore

Due to the scaled-down plans, Melaka Gateway’s competitiveness and importance as a strategic facility on the Strait of Malacca has also been diminished, while the narrative that the combination of Melaka Gateway plus the East Coast Rail Line would create a viable new trade route bypassing Singapore entirely now seems like a pipe dream.

In an interview with Lianhe Zaobao, Hutchinson said the narrative that the Melaka Gateway project could pose a challenge to Singapore was rather misplaced. “The argument was that goods would go to Melaka, be offloaded, transported across peninsular Malaysia, then reloaded on the East Coast before being shipped elsewhere.

“Cargo operators are never supportive of these arrangements as it increases their risk and insurance premiums,” he explained. “It does not increase efficiency nor decrease transit times.

“Thus, this was never really a concern and is less of one now.”

Malaysia would have to observe sentiments in Indonesia before embarking on mega projects the scale of the originally planned Melaka Gateway, as its location was not far from Indonesia. — Assistant Professor Goh Hong Lip, Belt and Road Strategic Centre, UTAR

Building an international cruise terminal to give tourism a boost

In an interview, Goh Hong Lip, an assistant professor at the Belt and Road Strategic Centre of the Universiti Tunku Abdul Rahman (UTAR), said Singapore’s Tuas Port is also expanding, and if the levels of efficiency in port management are maintained, Malaysian ports will not be able to surpass Singaporean ports in the short term.

He also cautioned that Malaysia would have to observe sentiments in Indonesia before embarking on mega projects the scale of the originally planned Melaka Gateway, as its location was not far from Indonesia.

Goh said frankly that BRI projects often start well, then go downhill. The focus of China’s recent BRI projects has also shifted from large scale infrastructure building projects to connecting people and cultural exchange.

“Malaysia, as an important partner in Southeast Asia for China, still hopes to play a key role in the BRI,” he said. “Although the two countries may have some disagreements on certain projects, they have not hurt the relationship between Malaysia and China.”

KAJD recently announced a partnership with Global Ports PLC — the world’s largest cruise port operator and listed in London — to build a port with several berths for cruise liners, with the objective of making Melaka the top cruise hub in Southeast Asia, attracting 3.5 million visitors annually.

Khoo Poay Tiong, Member of Parliament (MP) for Kota Melaka, told Lianhe Zaobao that Melaka had a clear geographical advantage, and was a transit point between Singapore and Port Klang. In addition, the Port of Melaka is just ten to 15 minutes by car from key tourist sights.

“This is very attractive to cruise operators, they have always suggested building a cruise terminal in Melaka. Studies by cruise operators and the government have shown if the terminal is built, it will help to boost development in the surrounding areas.”

However, according to the analysis in Tham’s article on the Fulcrum website, there is already considerable competition for cruise tourism on the west coast of peninsular Malaysia. In Penang, for example, the expansion of Swettenham Pier Cruise Terminal was completed in 2021 and now allows two mega-sized cruise liners to dock and can handle 12,000 passengers at the same time.

Plans to develop Port Klang into a home port for international cruises were also announced by the Malaysian government in January this year — a home port is far larger than a cruise terminal for docking liners.

Tham also pointed out that Penang, which has better-developed infrastructure for tourism, received 500,000 international cruise passengers last year, making the goals Melaka Gateway is setting seem overly optimistic.

“There are challenges in sustainability when large numbers of cruise tourists disembark in a small city like Melaka.” — Tham Siew Yean, Visiting Senior Fellow, Malaysia Studies Programme, ISEAS

Slow construction and unhappiness about environmental impact

“Global growth is to slow down, and it will be difficult to attract investors to develop cruise ports,” said Tham.

Tham felt attractive tourism products are required to draw cruise tourists, while Melaka will also need to protect its cultural and historical heritage. “There are challenges in sustainability when large numbers of cruise tourists disembark in a small city like Melaka.”

It has been a decade since plans for Melaka Gateway were first announced, but progress has been slow, leading to a sense of helplessness among locals. Many have adopted a wait and see attitude in reaction to the plans for building an international cruise terminal.

Melaka resident Eduan told Lianhe Zaobao that if the cruise terminal is indeed completed, he would be happy, because it would attract more visitors to Melaka.

Another resident, Guna, said if the project develops in the right way, and is complemented by marketing and promotion campaigns, it would benefit Melaka.

“But if it becomes another white elephant project, or remains unfinished after raising funds, then of course I won’t support it.”

MP Khoo Puay Tiong, stressed that the state government told KAJD to ensure that the terminal would be completed by late 2025 before it was allowed to restart construction.

“The Melaka Gateway project started in 2014 and has now been delayed for almost ten years, so we told the developer to focus first on the construction of the cruise terminal,” Khoo said. “Right now, we have not seen construction restarting, but we will continue to monitor the situation closely.”

The project is also drawing the ire of some local conservation organisations because construction work had damaged the livelihood of fishermen in the Portuguese Settlement area.

Local conservation group SOS Melaka told Malaysiakini in March last year, “According to our surveillance, an estimated 60% of the reclaimed land area is not protected by any breakwaters, so the surrounding shores keep facing problems with erosion and pollution.”

Khoo stressed that the Melaka Gateway project has to abide by the environmental evaluation report, and cannot push ahead with development plans single-mindedly and cause damage to the Melaka shoreline.

Due to the persistent delays in the Melaka Gateway project, the revival plan does not seem to have drawn too much attention in Malaysia. Several analysts were not up to date with the latest development in the project, and many others have all but forgotten its existence.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “从区域最大港口缩减成游轮码头 马六甲皇京港雷声大雨点小”.