[Big read] With real estate’s heyday over, China hunts for its next growth engine

From a plot of land to a new home, it does not just involve China’s real estate sector alone, but an entire system. If a critical link in the system goes wrong, related parties would come under pressure. Lianhe Zaobao journalist Liu Sha takes a look at how the upstream and downstream real estate industrial chain has been affected by the sector’s slump.

“I shut down the company-operated stores on 7 December 2022,” Wu Yingjie said without hesitation, as he scrolled through his phone to send me dozens of photos from his former stores.

Wu, 41, began taking on interior painting projects in Guangzhou and Foshan in his early 20s. He painted villas and even large projects such as the Qingdao Vanke City.

Real estate’s last hurrah

During the initial Covid-19 pandemic lockdown in early 2020, many renovation orders were halted. In the second half of the year, the first wave of the pandemic was brought under control, restrictions across regions were lifted, and economic activities quickly resumed.

To Wu’s surprise, orders for the company doubled. “Customers were especially decisive in placing orders. It felt like revenge consumption,” he shared.

In hindsight, he realised that period of prosperity was the industry’s last hurrah before a long-term downturn.

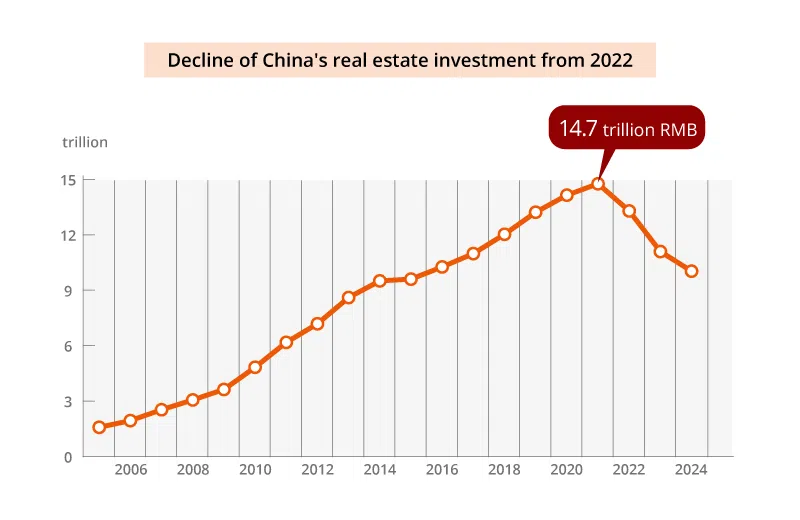

Macro data reflected this peak: in 2020, Guangzhou sold 146 parcels of commercial land, totalling 246.5 billion RMB (US$34.32 billion). Transaction value and building areas both hit record highs, while housing prices in the city exceeded 33,000 RMB per square metre. For the first time, national real estate investment exceeded 14 trillion RMB. Wu said, “Back then, everyone believed that house prices would only rise and never fall.”

However, there was already a cooling down on the policy side. In August 2020, the People’s Bank of China and the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development along with 12 real estate firms held a meeting to establish the “three red lines” on debt ratios for real estate companies, marking the start of the industry’s deleveraging.

Over the next two years, leading property developers such as Evergrande and Country Garden plunged into financial crises, with broken capital chains leading to projects failing to meet delivery deadlines, and in turn a sharp decline in renovation demand.

No more renovations

Property developers seeking Wu’s services for showrooms significantly decreased. Villa owners who had planned lavish renovations began hesitating whether to go ahead or sell off their property. Coupled with the resurgence of the pandemic and local lockdowns, orders that Wu had already signed were delayed or cancelled.

Wu said, “The year 2022 was truly a turning point. Our orders dropped from 50 to 60 per month to just a handful. It was a huge blow.” He made mass layoffs, reducing his team of over 100 to less than ten people, and closed all 17 stores in Guangzhou, including his flagship store in Panyu, a personal favourite.

“I spent 1.5 million RMB meticulously decorating the store. Closing it was gut-wrenching, but not doing so meant another rental cost,” he lamented.

Industry media New Paradigm of Home Furnishing reported that over 100 interior design companies went bankrupt and were liquidated in the first half of 2025.

China’s booming real estate investment contracted in 2022, the first time in 20 years. Real estate development investment peaked at 14.7 trillion RMB in 2021, then continually declined, shrinking by over 4 trillion RMB in three years to 10.02 trillion RMB in 2024.

In terms of the real estate crisis, external observers often focus on the collapse of Evergrande and Country Garden, but for industry insiders, the pressure continues to ripple outwards.

Erin Xin, HSBC economist for Greater China, said that China’s real estate sector has experienced a prolonged downturn in recent years and has yet to fully stabilise. Real estate investment, housing prices and new home sales have seen deeper declines this year, consistently underperforming expectations and inevitably adversely impacting related industries.

Thousands of construction and renovation companies bankrupt

Gu Qingyang, an associate professor from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP) at the National University of Singapore (NUS), stated when interviewed that the real estate industrial chain is massive and far-reaching. From a plot of land and a building to a new residential home, it does not just involve a single industry, but an entire system. If a critical link in the system goes wrong, related parties would come under pressure.

In April 2025, Zhufaner, a unicorn in the interior design industry, collapsed because of a break in its capital chain. Its Shanghai headquarters were vacated due to unpaid rent and over 800 construction sites were shut down. In July, Guangzhou interior design firm Liangjiaju, with a 24-year history and nearly 100 branches, was reported insolvent. The company announced its closure the day after its 53-year-old founder Zeng Yuzhou fell to his death.

“At its peak, the entire upstream and downstream industrial chain contributed about 30% to the economy. Once it contracts, the drag on the economy would be very apparent.” — Associate Professor Gu Qingyang, LKYSPP, NUS

Industry media New Paradigm of Home Furnishing reported that over 100 interior design companies went bankrupt and were liquidated in the first half of 2025.

The furniture industry is also rife with bad news. Wang Linpeng, chair of China’s largest furniture retail chain Easyhome, was detained for investigation in April and tragically died at home in July. The founder of another industry giant, Red Star Macalline’s Che Jianxing, was put under investigation in May and has not been heard from since.

The downturn in the interior design and furniture industries has also affected upstream sectors, such as building materials and construction. From January to November 2024, over 2,400 construction companies went bankrupt and underwent restructuring.

Gu pointed out that over the past 30 years, the real estate sector has played multiple roles: it has been a major part of fixed investment and residential investment, while contributing to local fiscal revenues, and also brought about a wealth effect for residents. “At its peak, the entire upstream and downstream industrial chain contributed about 30% to the economy. Once it contracts, the drag on the economy would be very apparent,” he said.

Gu added that from a cyclical perspective, the worst of the economic drag from real estate might be over, but the negative impact is still rippling across the upstream and downstream sectors.

Taking Guangdong as an example, both Guangzhou and Foshan have long benefited from industrial clusters formed by real estate expansion, with many cities having mature home furnishing-related industries, such as furniture in Foshan and Dongguan, lighting in Zhongshan, and ceramics in Chaozhou. However, over the past two years, due to the contraction of the real estate market, demand has significantly decreased, dragging down overall economic growth.

Last year, Guangdong’s GDP grew by just 3.2%, failing to meet the target for the second consecutive year. In the first half of this year, it grew by 4.2% — also below the 5% target. Industry insiders believe that Guangdong’s ability to meet its expected target this year would depend on the stability of the real estate market.

A systemic drag

Gu stated that the Chinese real estate market has not yet bottomed out and stabilised, and that it would take time to resolve the systemic drag.

When Gu visited the China International Building Decoration Fair in Guangzhou in March, he saw that many companies in the upstream and downstream industrial chain were not sitting around waiting for a recovery in real estate. Instead, they chose to develop in various ways: by reducing costs, incorporating intelligence into their businesses and venturing abroad. Despite the struggle and unavoidable growing pains, the businesses believe that they can ultimately transform.

... customers’ renovation budgets have generally shrunk this year. A homeowner with a 120-square-metre apartment with three bedrooms and two living rooms would have had a budget of at least 500,000 RMB two years ago, but now it could be 300,000 RMB. — Sun Hao (pseudonym), operator of a home lighting business in Beijing

Sun Hao (pseudonym, 45), whose hometown is in Zhongshan, Guangdong, and who has been operating a home lighting business in Beijing for many years, said that while he did not expect to make a fortune, there are still ways to make a living.

He said that customers’ renovation budgets have generally shrunk this year. A homeowner with a 120-square-metre apartment with three bedrooms and two living rooms would have had a budget of at least 500,000 RMB two years ago, but now it could be 300,000 RMB. “Consumer expectations have not lowered, but they’re more practical now, hoping to stretch every dollar.”

Ongoing involution

Involution has become almost unavoidable. Sun said, “There’s only so much demand. Distributors are afraid of losing customers, and factories are afraid of losing distributors, so price cuts start right from the factory.” He emphasised, “This is all voluntary, not forced.”

It is not just about competitive prices; the service must also be solid. Sun said that the company’s customer service and designers are basically on call 24/7, not daring to delay responding to customer inquiries.

Everyone talks about venturing abroad, and Sun has also tried to expand sales channels. Last month, he collaborated twice with TikTok’s live-streaming company in Thailand. However, he found that “foreign trade is also very competitive, with even harsher price constraints and a profit margin of less than 15%”.

Era of slim margins

Wu Yingjie said that the profit margins on his projects have shrunk to historic lows, “We’re in the ‘era of slim margins’ now — any morsel of profit is better than none. The days of soaring property prices and surging orders are over.”

He admitted that it was painful to shut down his store, but feels some relief now as “at least it turned out to be a timely decision to cut losses”.

Nonetheless, he remains optimistic and sees the current phase as practising “turtle breathing” — taking on small orders to keep the business going while using some savings to invest in a guesthouse in his hometown of Huizhou. He said, “People are easily stressed these days, so they enjoy going somewhere picturesque to lift their spirits.”

Now, minimalist ceiling lights without the frills are the bestsellers.

Sun Hao also believes that consumer demand still exists, just that it has changed. “In the past, every living room had to have a big chandelier — crystal, copper, Baroque style. That was the aesthetic of economic expansion,” he noted.

Now, minimalist ceiling lights without the frills are the bestsellers. Sun sees nothing wrong with the shift towards practicality, tech-inspired designs, and value for money. “Times have changed, and people need to adapt accordingly,” he said.

Unlikely to return to old model of real estate-driven growth

China’s current real estate crisis has yet to be resolved, with its impact spreading both upstream and downstream. Meanwhile, tariff tensions are piling on, posing serious challenges to the country’s economic growth, with persistent calls for large-scale stimulus.

Notwithstanding, the Chinese government did not introduce large-scale stimulus measures, instead adopting supporting measures such as lower mortgage rates, a “whitelist” of real estate projects and guaranteed housing delivery, to stabilise the market and halt its decline.

At the Central Urban Work Conference in July, it was stated that China’s urban development is shifting from large-scale incremental expansion to improving the quality and efficiency of existing capacity.

Interviewed academics believe that all signs suggest that despite the challenges, the Chinese government is unlikely to return to the old model of real estate-driven growth.

Professor Kent Deng from the Department of Economic History, London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), said in an interview, “Real estate, once a key engine of China’s economy, has stalled and can no longer serve as a driver of growth.”

Deng pointed out that China is facing a severe housing surplus. With slowing population growth and weakening income expectations, it may take ten years or more to fully absorb the excess inventory. Ultimately, this surplus will become debt rather than assets. “China’s policymakers are well aware of this,” he added.

“Real estate is becoming a regular livelihood sector, and that direction is not going to change.” — Andy Xie, a Shanghai-based independent economist

Andy Xie, a Shanghai-based independent economist and former Morgan Stanley Star Chief Asia-Pacific economist, also assessed in an interview that China’s real estate sector will not see a “second spring”. He noted that as early as 2016, Chinese President Xi Jinping had already declared that “houses are for living in, not for speculation”, making the government’s stance clear.

Xie pointed out that some local governments have resumed land transfers this year to stabilise buyer sentiment, ease selling pressure and avoid a hard landing. However, this does not signal a policy shift. “Real estate is becoming a regular livelihood sector, and that direction is not going to change,” he noted.

As one of the earliest economists to warn about China’s real estate bubble, Xie said that the bubble only burst after the government introduced the “three red lines policy”, because it had long been propped up by “non-market forces” — local governments were overly reliant on land sales for revenue and effectively became major players in the property market. This caused significant problems for both economic and social development.

Bailing out developers would only create more hidden risks

Xie said that China’s top leadership is currently politically stable and also more inclined towards long-term planning. He believes that the real estate bubble has created massive bad assets and debt, posing a threat to the financial system. Bailing out developers or launching large-scale stimulus would only plant more land mines for the future.

Some people think that the government still needs a thriving property market to support land finance. Xie pointed out that in the past, local governments spent heavily on infrastructure projects. But with China’s infrastructure now largely complete and the central government’s demands shifting, they should re-evaluate how much budget is truly needed for future development.

In the future, China may also consider expanding the tax base — such as through property tax — as a way to boost local government revenue.

Xie thinks that after China’s real estate bubble burst, the country did not fall into a prolonged slump like Japan once did. This has given the Chinese government confidence to maintain its current pace of adjustment.

... the negative wealth effect of the property slump has mainly impacted mid- to high-end consumption, with limited effect on people earning less than 10,000 RMB per month. — Xie

He explained that China’s situation is different from Japan’s: in China, a significant share of housing comes from demolition and relocation programmes, and most ordinary citizens have practically no debt, with mortgages being primarily carried by the urban middle class. As a result, the negative wealth effect of the property slump has mainly impacted mid- to high-end consumption, with limited effect on people earning less than 10,000 RMB per month.

Another key difference is that unlike Japan, which focused on restoring the old order, China aims to reshape and build a brand new economic system through technological breakthroughs to boost productivity. “China doesn’t look back,” he said.

No more relying on a single sector as a universal engine

There is broad consensus that China’s economic growth needs to shift gears. In recent years, much debate has focused on what could replace real estate. The rise of new energy vehicles has raised high hopes for the auto industry, but compared with real estate, cars are less able to replicate the “wealth effect” that property can bring.

NUS’s Gu thinks that the past 30 years were unique — real estate fuelled land finance, offered households an investment avenue, and expanded wealth effects. From this perspective, no single industry today can fully “replace” real estate.

But he stressed that China’s economic transition relies on “new quality productive forces”, driven by sectors such as new energy vehicles, semiconductors and artificial intelligence, gradually taking over real estate’s past role in investment and growth. He said that in the future, China’s economy will not and should not rely on a single industry as a “universal engine”.

LSE’s Deng added that the real challenge in China’s economic transition lies in its export-oriented structure. If external demand weakens, industries such as automobiles, solar panels and ships could all face overcapacity.

“Whether it’s houses or cars, if China’s workforce can secure higher wages and better welfare benefits, and overall income rises, then there won’t be overcapacity — because the builders of the houses will be able to afford them.” — Professor Kent Deng, Department of Economic History, LSE

Deng explained that while China’s manufacturing capabilities are world-class, they rely on offering high quality at low prices to win the market. This model forces supply chains to constantly cut costs, leaving companies with thin profits and offering little household wealth effect. Moreover, once access to international markets is restricted, overcapacity becomes inevitable.

“Houses cannot be exported — if you build too many, you have to absorb them yourself. While vehicles can be exported, overcapacity will still be a problem if international restrictions arise,” he noted.

Deng said that while China is capable of overcoming technological blockades and strives to innovate despite the obstacles, any growth model that depends on exports to be profitable comes with serious question marks.

To address this problem, he thinks that it is still essential to unlock the domestic market’s consumption potential, reform income distribution and support people’s livelihoods — only then are people willing to spend, making it possible to change the growth model. He pointed out that China’s economic growth has not kept pace with income growth — after deducting essential expenses such as mortgages, education, retirement and healthcare, ordinary people have limited disposable income.

He said, “Whether it’s houses or cars, if China’s workforce can secure higher wages and better welfare benefits, and overall income rises, then there won’t be overcapacity — because the builders of the houses will be able to afford them.”

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “中国楼市阴霾不散 上下游苦撑盼蓝天”.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)