Can private enterprise thrive under Xi’s rule?

Was the recent symposium on private enterprises a real message to the private sector in China, or was it just lip service? Does China really have a strong enough private business sector that can keep pace with innovation in the West? EAI senior research fellow Lance Gore explores the issue.

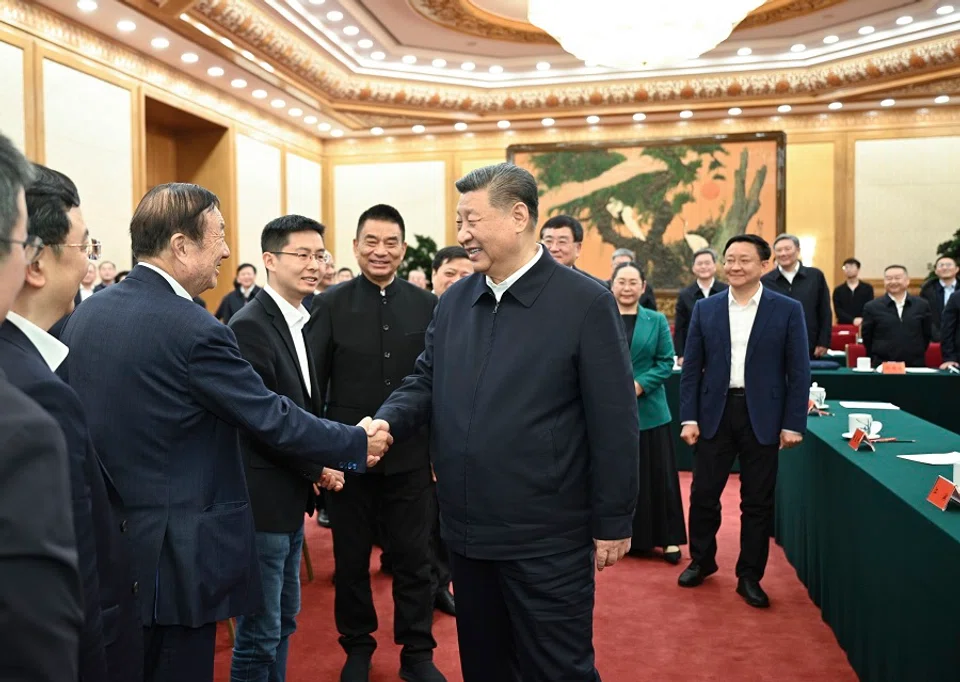

On 17 February, Chinese Communist Party (CCP) General Secretary Xi Jinping held yet another symposium with private entrepreneurs, with executives from technology and innovation enterprises in the front row, directly facing the top CCP leadership. This is amid the ramped-up promotion of Hangzhou’s “Six Little Dragons”, a group of influential high-tech companies that have emerged in Hangzhou in recent years, including DeepSeek, which is making waves in the Western artificial intelligence (AI) sector.

Political messages and their meanings

Some local governments are asking why the Six Little Dragons did not emerge in their regions, and how their business environments differ from Hangzhou’s. It is said that the Hangzhou government is transparent and efficient — officials do their jobs and then fade out, without bothering businesses or ordering them around. Notably, among the current seven members of the Politburo Standing Committee, three have previously served in Hangzhou.

One focus of this symposium was the attendance of Alibaba founder Jack Ma. Many interpreted this as a sign of a new direction in the CCP’s policy toward private enterprises, who now have a higher role in driving innovation and developing new productive forces.

Xi’s last symposium with private enterprises was in November 2018, when the idea of “private enterprises exiting the stage” was circulating. He responded that assertions suggesting private enterprises should exit or that the mixed-ownership reform is a new public-private partnership are incorrect. Additionally, claims that party-building and union activities are meant to control private enterprises misrepresent the party’s major policies.

Following the meeting, state media emphasised that private enterprises are “one of us” and, rather than exiting the stage, should move toward an even bigger platform.

Fleeing private entrepreneurs

Over the past five years, successive regulatory crackdowns on the real estate sector, private tutoring industry, gaming, platform economy, and internet finance have dealt severe blows to private enterprises. From the suspension of Ant Group’s IPO in November 2020 to July 2023, the combined market value of Alibaba, Tencent, and three other tech giants shrank by over US$1 trillion.

In 2024, an estimated 15,200 HNWIs emigrated from China, mainly to the UAE, the US, Canada, Singapore and Japan, contributing to a capital loss of about US$1 trillion.

In January 2023, Ant Group announced a restructuring of its ownership, with Jack Ma relinquishing actual control. Six months later, the company was hit with a fine of over 7 billion RMB (US$960.8 million). Subsequently, Jack Ma moved overseas, settling in Japan. Meanwhile, a wave of crises engulfed property developers like Evergrande, whose founder, Hui Ka Yan, was detained, leading to rock-bottom confidence among private enterprises.

At the symposium, Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei expressed concerns over the ongoing talent drain. Since 2015, China has consistently been the largest source country for high-net-worth individual (HNWI) emigration. In 2024, an estimated 15,200 HNWIs emigrated from China, mainly to the UAE, the US, Canada, Singapore and Japan, contributing to a capital loss of about US$1 trillion. The figures for 2023 and 2022 were 13,800 and 10,800 individuals respectively.

On the other hand, China has continuously adopted measures to protect private enterprises, including the 36-point guideline on the non-public sector (非公36条) issued in late February 2005, the “new 36 measures” (新36条) in May 2010 (five years after the original 36 points), the “28 measures” (28条) following the private enterprise symposium in November 2018, and another 31-point guideline (民企31条) introduced in July 2023, emphasising enhancing technological innovation capabilities.

On the legislative level, China’s constitution has undergone several significant amendments regarding the protection of private property. The 1988 amendment allowed for the existence of the private businesses and recognised it as a “supplement to the socialist public economy”. The 1999 amendment confirmed the “socialist market economy”, elevating the status of the non-public economy, emphasising that it is an “important component” of the socialist market economy rather than merely a supplement to public ownership. The 2004 amendment explicitly states: “Citizens’ lawful private property is inviolable… The State, in accordance with law, protects the rights of citizens to private property and to its inheritance.”

... they contribute more than 50% of tax revenue, over 60% of GDP, more than 70% of technological innovation achievements, over 80% of urban employment, and more than 90% of the total number of new enterprises.

The private sector now accounts for more than the commonly cited “half of the country’s economy”. At the recent symposium, Xi Jinping summarised the contributions of private enterprises as “five-six-seven-eight-nine” — they contribute more than 50% of tax revenue, over 60% of GDP, more than 70% of technological innovation achievements, over 80% of urban employment, and more than 90% of the total number of new enterprises.

By these measures, the status of private enterprises should not be a problem, as their share of GDP is close to that of some capitalist countries such as Norway, France, UAE, Brazil and India. However, unlike these countries, in China, “capitalists” and other “HNWIs” often get spooked at the slightest policy shift, like stray dogs. The recent regulatory adjustments targeting private enterprises would be considered normal in other countries — they would not be escalated to the level of “crackdowns” on private enterprises, requiring repeated reassurances from the country’s top leadership.

This is because China’s socialist market economy has two inherent deficiencies.

Vague status of entrepreneurs

Firstly, entrepreneurs occupy an inherently vague status. As the main drivers of a market economy, their entrepreneurial spirit fuels economic dynamism. Despite constitutional amendments and regulations, private enterprises have faced challenges in gaining legal recognition. Meanwhile, the top management of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) is appointed by the CCP’s Organization Department, making them subordinate to the party-state. In the political power structure, both private and state-owned enterprises are subordinate entities. Aligning with political power is an effective way to protect their interests.

Their [officials’] impunity highlights the second-class status of private entrepreneurs.

When private enterprises succeed, they often draw attention from government officials eager to associate with them. As a business executive from Hangzhou noted, “The sheer number of study delegations and inspection teams, drinking until they’re staggering — any boss would be terrified.” Some local governments and officials lack integrity, frequently defaulting on payments owed to private enterprises, effectively becoming “deadbeat debtors”. Their impunity highlights the second-class status of private entrepreneurs.

The establishment of a Bureau of Private Economy under the National Development and Reform Commission is one of the few substantive reforms in the past 40 years. However, within the broader power structure, it remains insignificant.

In this national hierarchy, retaining talent often relies on material incentives. At the symposium, Xi emphasised that China’s “well-developed industrial and infrastructure systems, along with a massive market of over 1.4 billion people, offer the private sector abundant new opportunities and greater room for development”.

Not an equal participant in the market

The second inherent deficiency arises from the official ideology, which underpins the existing power hierarchy. So far, ideological innovation has not successfully reconciled the core Marxist theories — like the abolition of private ownership and exploitation, class struggle, the dictatorship of the proletariat, and the realisation of communism — with the principles of a market economy.

The ideological bias here treats these two economic forms as separate and opposing entities, rather than as equal participants in the market.

The arduous process of introducing market mechanisms in China highlights this tension, moving from “cutting off the capitalist tail” to the “birdcage economy”, then the “market as a supplement”, followed by the “planned market economy”, and finally to the “socialist market economy”. Recently, “the leadership of the Communist Party” has replaced “socialism”, with nods to Confucianism and other cultural traditions. Despite these adjustments, entrepreneurs have often been marginalised in various ways.

In the “socialist market economy”, the role of private enterprises is largely defined by the principle of “adhering to two unwavering commitments”: steadfastly consolidating and developing the public economy while also encouraging, supporting, and guiding the growth of the non-public economy. The ideological bias here treats these two economic forms as separate and opposing entities, rather than as equal participants in the market.

When China introduced the “31 measures” mentioned above, former Global Times editor-in-chief Hu Xijin interpreted it to mean “true equality between the private and the state-owned economy”. However, he was reprimanded for this remark and his internet accounts were shuttered for a month as punishment.

Private enterprise owners are more sober — they know their place and risks. The ideological indoctrination from the Mao era has heightened sensitivity to wealth disparity among the Chinese public, with envy and resentment toward the wealthy still common. These sentiments often influence government actions, as the historical tendency of leftist thinking makes “robbing the rich to give to the poor” an almost instinctive reaction. The extreme left has always had a strong ideological foundation, political influence and public support, making it easy for them to incite unrest.

This is precisely why Deng Xiaoping once warned: “We must be wary of the right, but the main danger comes from the left.”

Innovation-driven economy presents CCP with a challenge

A key backdrop to this symposium is the rise of AI as a general-purpose technology, permeating all industries and becoming the primary driver of economic growth. This also adds urgency to the CCP’s push for “new quality productive forces” following the 20th Central Committee’s Third Plenary Session. The storm triggered by DeepSeek has demonstrated the immense power of technological innovation and entrepreneurship in the knowledge economy. History has shown that innovations in today’s economy are highly decentralised, often emerging from unknown small enterprises and individuals.

... should it continue supporting state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and mobilising national resources for large-scale projects under a state-led model, or should it create an environment that allows unexpected disruptors to emerge from all corners of society?

Bill Gates recognised this characteristic of the new economy early on. During his tenure as Microsoft’s CEO, he said large corporations such as IBM, Intel, HP, and Dell were not on his radar — only small, agile startups had the potential to disrupt Microsoft.

The innovation-driven economy presents the CCP with a challenge: should it continue supporting state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and mobilising national resources for large-scale projects under a state-led model, or should it create an environment that allows unexpected disruptors to emerge from all corners of society? This is a strategic adjustment that could shape the nation’s future.

Decades ago, the unexpected rise of township and village enterprises (TVEs) caught Deng Xiaoping by surprise, as they were not part of his original vision. More recently, Elon Musk’s SpaceX, founded in 2002, has surpassed China’s state-led aerospace industry — boasting a history of over 70 years — in several key areas, such as heavy payload capacity and rocket recovery technology. Even NASA has been humbled by its achievements.

The innovation economy is driven by knowledge- and technology-based entrepreneurship. Their rise is difficult to predict and even harder to control. This shift significantly strengthens the role of private enterprises, forcing ideological and governance models to adapt while challenging Marxist views on private ownership, capitalists, and historical progress.

These modern entrepreneurs are workaholics, not an idle elite. They are good at getting things done but are not good at socialising and are often at odds with bureaucratic culture. They are a new class of capitalists whose main asset is intellectual property.

Socialism and common prosperity?

At the symposium, Xi Jinping expressed his hope that private enterprises would “first become prosperous and then promote common prosperity”. This touches on another key ideological issue: socialism.

History may eventually prove that common prosperity — and even communism — could emerge from new capitalists rather than the proletariat. Some of America’s wealthiest capitalists, such as Elon Musk, Warren Buffett, and Bill Gates, are also social activists. They use capital accumulation as a means to pursue socialist objectives, integrating social and environmental concerns into market operations to dilute, constrain, and transform the traditional logic of capital, thereby mitigating its alienating effects. Gates has argued that only socialism can resolve many of the challenges facing humanity.

Many prominent tech leaders, including Gates, Musk and the father of AI Geoffrey Hinton have publicly identified as “socialists” on different occasions.

A blog entry by Elon Musk promises that Tesla “will not initiate patent lawsuits against anyone who, in good faith, wants to use our technology”. Musk elaborated: “If somebody comes and makes a better electric car than Tesla, and it’s so much better than ours that we can’t sell our cars and we go bankrupt, I still think that’s a good thing for the world.”

Silicon Valley, often seen as the heart of capitalism, is also the centre of the Universal Basic Income (UBI) movement — a policy rooted in the socialist ideal. Many prominent tech leaders, including Gates, Musk and the father of AI Geoffrey Hinton have publicly identified as “socialists” on different occasions.

All this can inspire ideological innovation.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “又一次民企座谈”.