China’s export machine stalls under Trump’s new trade blitz

Under Trump’s newly unveiled “reciprocal tariff” system, Chinese exports face a 34% increase on top of the existing 20% duties, pushing total tariffs to 54% starting 9 April. Simultaneously, the US will end duty-free exemptions for small parcels valued under US$800 and impose new tariffs by 1 June.

(By Caixin journalists Feng Yiming, Tan Min, Zhao Xuan, Lu Yutong, Bao Yunhong, Luo Guoping, Qu Yunxu, Fan Ruohong, Bao Zhiming and Denise Jia)

Chinese manufacturers are scrambling to respond after US President Donald Trump announced sweeping new tariffs on Chinese goods, delivering the heaviest blow yet to industries already reeling from years of trade tensions.

Under Trump’s newly unveiled “reciprocal tariff” system, Chinese exports face a 34% increase on top of the existing 20% duties, pushing total tariffs to 54% starting 9 April. Simultaneously, the US will end duty-free exemptions for small parcels valued under US$800 and impose new tariffs by 1 June.

The tariff hikes hit labour-intensive industries hardest. For apparel, furniture and footwear companies, total tariff rates could now reach 79% — levels most cannot survive.

“This time, even cross-border small parcels are taxed. The supply chain simply can’t absorb this cost increase,” said Jerson Wong, head of an underwear and apparel company in Shantou, China’s largest lingerie manufacturing hub. Wong’s company relies on the United States for 40% of its sales and pivoted to e-commerce in recent years. “When I woke up, my entire WeChat feed was filled with news about the tariffs,” he said.

The double blow to traditional exports and e-commerce has shocked Chinese factories already under pressure. Apparel products were hit with a 25% tariff during Trump’s first term, followed by two additional 10% hikes this year. Wong said US importers have told clients they plan to cut sourcing from China from 80% to zero, citing weak consumer demand.

Many manufacturers had shifted to direct-to-consumer e-commerce in the US to sidestep middlemen. Now, with the loss of small-parcel exemptions, that strategy is collapsing. Wong said his company has stopped investing in the US and is redirecting efforts toward semi-managed exports via overseas warehouses while expanding into Europe through platforms such as TikTok.

The tariff hikes hit labour-intensive industries hardest. For apparel, furniture and footwear companies, total tariff rates could now reach 79% — levels most cannot survive. Many exporters say they no longer care whether the final tariff is 54% or 79%, given their slim 10% to 15% margins.

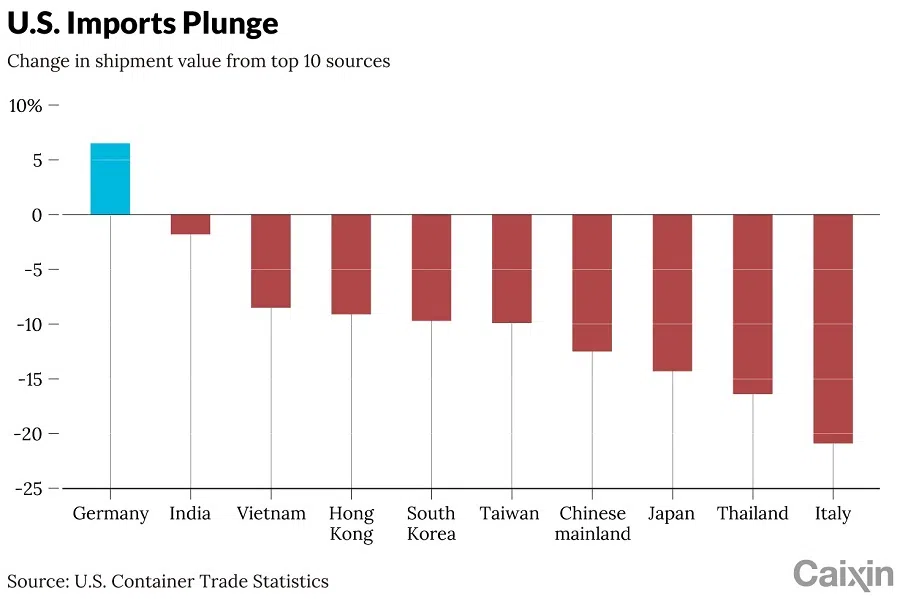

In January and February, China’s exports of clothing, furniture, footwear, hats and toys to the US already fell sharply year-on-year. Facing growing pressure, Chinese exporters are now scrambling to find new markets in Southeast Asia, Europe and Russia — but hurdles are high, including payment risks in Russia and fierce competition in Southeast Asia.

Meanwhile, plans to move production to Southeast Asia have stalled. Wong said his company stopped building on a 90-acre manufacturing facility in Vietnam after Trump announced that goods from Vietnam would face tariffs as high as 49%. Under these tariffs, moving capacity abroad no longer makes sense, he said.

The biggest losers may not be China or the US, but other developing nations now forced to compete with China’s highly efficient, low-margin manufacturers. — Craig Allen, Senior Counsellor, Cohen Group

Facing mounting trade barriers, Chinese manufacturers are calling for industrial upgrades and stronger intellectual property protection. Exporters interviewed by Caixin said that European and American supply chains remain too weak to fully replace China’s manufacturing base. Without price advantages, survival depends on innovation and higher quality.

“We have to develop new products faster and protect them from being copied if we want to maintain pricing power. If we keep competing on low prices, none of us will survive,” Wong told Caixin.

Trade experts warn that Trump’s tariffs will reshape global manufacturing patterns. The biggest losers may not be China or the US, but other developing nations now forced to compete with China’s highly efficient, low-margin manufacturers, said Craig Allen, senior counsellor at the Cohen Group and former head of the US-China Business Council.

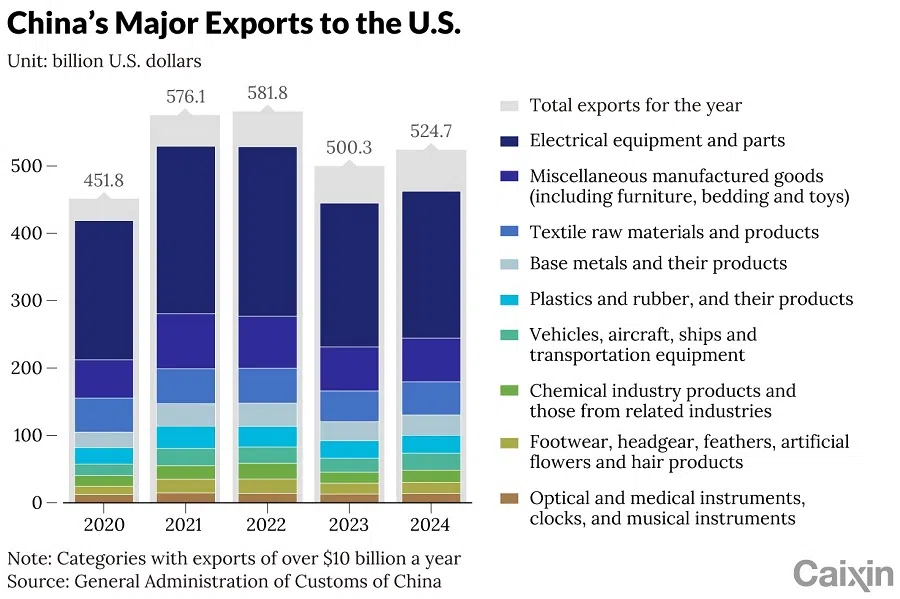

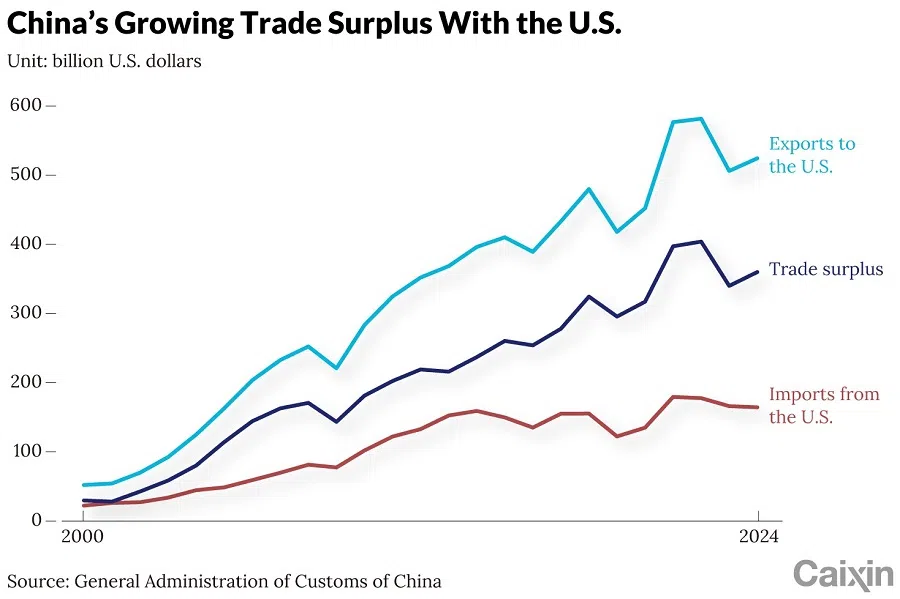

The US remains China’s largest trading partner, accounting for 14.7% of total exports in 2024, worth US$524.66 billion. China’s top exports to the US — machinery, steel, aluminium, plastics, clothing, toys and furniture — are largely labour-intensive products, now firmly in the crosshairs of higher tariffs.

Labour-intensive sectors hit

A report by China Chengxin Credit Rating Group warned the impact would be especially severe for raw materials and labour-intensive sectors. Analysts expect exports to stay under pressure as trade tensions escalate and supply chains shift.

Chinese labour-intensive industries were already struggling under earlier tariffs of up to 25% imposed during Trump’s first term. Since then, exports to the US have steadily declined. According to Chinese customs data, exports of furniture, bedding, lighting and toys in 2024 fell 21% from their 2021 peak, while footwear and apparel exports dropped 25% in 2023 before recovering slightly last year.

Hu Jie, professor at the Shanghai Advanced Institute of Finance at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, said Chinese factories had absorbed much of the earlier costs through discounts and cost-cutting, but warned they are now at the limit. “Giving up the US market isn’t realistic,” said Hu. “But absorbing further tariffs will be extremely hard.”

With margins often below 20%, splitting tariff costs with US buyers increasingly results in direct losses. “Some large factories shipping millions of products each month are operating at near-zero margins,” said a Guangdong handbag exporter. “And with the US buying 30% of the world’s footwear and apparel, finding new markets quickly isn’t easy.”

The tariff hikes have hit China’s major industrial belts — Guangdong, Fujian, Shanghai and Qingdao — particularly hard. Some areas account for half of the global output in categories such as toys. Chenghai District in Shantou alone produces 50% of China’s plastic toys and a third of global supply.

Exporters now face a grim choice: pass higher costs on to American consumers or absorb the tariffs themselves. “Historically, tariffs are ultimately paid by American businesses and consumers,” said Han Lijie, a partner at Katten Muchin Rosenman LLP. Meanwhile, Chinese exporters with stronger innovation and brand strength may weather the storm better, while weaker players risk being pushed out.

Some companies are already walking away. A Dalian-based glassware exporter said US buyers absorbed earlier tariffs but warned they would now rather abandon the American market than make further concessions. “Better to lose the market than to feed the tiger,” the exporter said.

Negotiations between Chinese and American firms are growing tougher. One textile exporter said an American client demanded price cuts to offset tariffs but talks stalled even before the latest 34% hike. With margins squeezed, exporters expect bargaining to become even more difficult.

Still, some see opportunity in adversity. Wu Yuqin, head of Shantou Feiying Technology Co. Ltd., said several toy exporters gathered at his office on 2 April after all US orders were abruptly halted. Wu believes that investing in artificial intelligence (AI) could help China’s toy industry rebound. “Europe doesn’t have what China’s AI sector can offer yet,” he said. “If we can launch AI-driven toys and update faster than copycats, we’ll find new markets.”

China’s booming cross-border e-commerce sector faces major disruption as the US moves to end tax exemptions on small parcels — a key advantage that fuelled years of rapid growth.

Small parcels, big trouble

China’s booming cross-border e-commerce sector faces major disruption as the US moves to end tax exemptions on small parcels — a key advantage that fuelled years of rapid growth.

Under new rules, shipments from mainland China and Hong Kong will soon face a 30% tariff or a US$25 fee per package, eventually rising to US$50 after 1 June. Only goods from Macau will have a 90-day review period. The change effectively ends the “de minimis” rule, which allowed tax-free entry for goods valued under US$800 under an “Entry Type 86” (T86) customs clearance process, a policy used by more than 1.3 billion packages in 2024.

To manage the surge in taxed shipments, US authorities said customs systems have been upgraded to collect new tariffs, following an executive order issued earlier this year.

While the industry largely expected the policy shift, confusion remains over how tariffs will be applied. “It’s unreasonable to pay a US$25 tax on a product that costs less than US$25,” said veteran seller Xiao Wang Ge, who added that merchants are unsure whether they will be taxed based on product value or flat fees.

Despite the confusion, some merchants plan to continue using the T86 customs entry route. Xiao Wang Ge pointed out that even with the new tariffs, shipping through small parcels still offers a cost advantage over traditional trade routes, where total tariffs often exceed 30%.

Small and mid-sized merchants reliant on platform-managed services will be hit hardest. Haige, CEO of Zhongyi Cross-Border, warned that more than half of direct-shipped parcels could see costs soar 30% to 50%. “For small sellers like me, it’s a devastating blow,” said an Amazon merchant specialising in customised goods. Many small sellers, especially those offering made-to-order goods, lack the capital or logistics to switch to the overseas warehouse model.

Major Chinese platforms including Shein, Temu (owned by Pinduoduo), AliExpress (Alibaba), and TikTok Shop also face challenges. These companies built their US presence by managing direct shipments for thousands of Chinese merchants. Together, Temu and Shein account for 30% to 40% of the US cross-border market, according to Citic Securities.

Recent data already shows stress. Bloomberg’s Second Measure reported that Shein’s US sales fell by 16% to 41% and Temu’s sales dropped up to 32% during a five-day stretch in February.

Shein’s business model — based on rapid “small-batch, fast-return” operations — may struggle the most. The company traditionally launches small trial batches based on digital demand tracking and social media trends, only mass-producing items that sell well. This model depends heavily on fast, tax-free small-parcel logistics. A forced shift to bulk shipping and warehouse stocking would erode Shein’s core competitive advantage: flexibility.

Meanwhile, operating overseas warehouses is getting more expensive. Although China offers tax rebates for warehouse exports, broader US tariffs on bulk shipments will raise costs. Unlike direct shipping, the warehouse model requires upfront investment in inventory, shipping and storage, stretching cash flow cycles from 30 to 100 days, a major burden for small sellers.

With about a month left before the new rules take effect, sellers are scrambling for alternatives. Some are considering underdeclaring goods to cut costs, but that strategy carries serious risks. “If you sell a US$10 shirt and declare it at US$1, customs will catch you,” warned one garment exporter.

Others are shifting stock to Vietnam and Myanmar, despite new tariffs there as well. “It’s the best strategy for now,” said the exporter, “even though logistics in Vietnam is still developing.”

Southeast Asia’s role as a manufacturing hub for US-bound goods is under threat as new American tariffs complicate Chinese companies’ efforts to shift production offshore.

Production pivot in trouble

Southeast Asia’s role as a manufacturing hub for US-bound goods is under threat as new American tariffs complicate Chinese companies’ efforts to shift production offshore.

Cambodian factories exporting handbags to the US — once enjoying near-zero tariffs — now face rates over 10%, potentially rising to 49%. “If tariffs rise to 49%, factories can’t survive,” said an executive at a Guangdong handbag manufacturer with operations in Cambodia.

Cambodia is among the hardest hit under the new tariffs. In 2024, US-Cambodia trade reached US$10.18 billion, up 11.2% year-on-year, with exports of textiles, apparel and footwear accounting for the bulk of Cambodia’s US$9.92 billion in shipments to the US.

Vietnam, Southeast Asia’s top US trading partner, also faces mounting pressure. In 2024, Vietnam’s exports to the US grew 23.3% to US$119 billion, while imports rose 7.3% to US$13 billion, driven largely by electronics and textiles. America’s trade deficit with Vietnam more than tripled over the last eight years, swelling from US$38.3 billion in 2017 to US$123.5 billion in 2024.

The solar industry is taking a major hit. Cambodia, Vietnam, Malaysia and Thailand — key nodes in China’s overseas solar production chain — have seen solar cell production grind to a halt. The US Commerce Department ruled in November 2024 that solar products from these four countries were dumped into the US below market value, with final tariffs to be announced in April 2025.

Tan Youru, BloombergNEF’s solar analyst, predicted emerging hubs such as the Middle East and Turkey could benefit. Trump’s new tariffs impose only 10% duties on Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar and Turkey.

Following the preliminary tariffs, some Chinese solar companies relocated production to Indonesia and Laos. Southeast Asia once supplied 82% of US solar panel imports, but that share dropped to 55% by December 2024. With tariffs rising, risks to Southeast Asian solar exports are escalating sharply amid global overcapacity and fierce price competition.

Tan Youru, BloombergNEF’s solar analyst, predicted emerging hubs such as the Middle East and Turkey could benefit. Trump’s new tariffs impose only 10% duties on Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Qatar and Turkey.

Manufacturers with dual operations in China and Southeast Asia are weighing their options. Hangzhou GreatStar Industrial Co. Ltd., Asia’s largest hand tool maker, said the tariffs would raise US prices industry wide. GreatStar vice-president Zhou Siyuan told investors at a 3 April roadshow that American market accounted for about 65% of the company’s total revenue, and some of its shipment came from Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand.

For tech giants, the impact could be stark. Apple, which manufactures mostly in China, Vietnam and India, faces tariffs of 54%, 46% and 26% respectively. “If production is split 65%/25%/10% across China, Vietnam and India, US iPhone prices could jump 30%,” Huatai Securities Co. Ltd. analyst Huang Leping estimated. Samsung, with 35% of revenue from the US, also faces steep tariffs on Vietnamese and Korean production.

Despite Trump’s push to bring manufacturing back to the US, industry leaders are sceptical. Zhou said GreatStar’s US capacity still relies on imported parts. High tariffs will drive up domestic production costs and worsen inflation, he warned. Ivan Lam, a senior analyst at Counterpoint Research, noted the US lacks the complete ecosystem for large-scale smartphone manufacturing, making a full return of companies such as Apple unrealistic.

Meanwhile, Latin America could become China’s new export gateway to the US Seven Asian shipping companies — including Sinotrans Container Lines Co. Ltd. and Emirates Shipping Line — will launch a Shanghai-Mexico express route on 30 April. China’s state-owned Cosco Shipping Corp. Ltd. also recently opened a new port in Peru, handling nearly US$300 million worth of goods in its first three months.

“The semiconductor industry thrives on global collaboration. Any unilateral action risks backfiring.” — Gao Shiwang, Spokesperson, China’s Chamber of Commerce for Import and Export of Machinery and Electronic Products

Exemptions offer short respite

The latest round of tariffs spares certain industries and countries — for now.

Exemptions cover semiconductors, automobiles, auto parts, energy and critical minerals the US lacks, as well as gold bars, copper, pharmaceuticals and wood products. Canada and Mexico, America’s top trading partners, are also excluded from the new tariffs — a move widely seen as a major concession. However, both countries still face existing tariffs on steel, aluminium and automobiles.

Semiconductors — long a flashpoint in US-China trade tensions — remain exposed. From January 2025, US tariffs on Chinese semiconductors doubled to 50%, up from the 25% rate set during the 2018 trade war. A new Section 301 investigation launched in December 2024 could lead to even broader restrictions.

“The semiconductor industry thrives on global collaboration. Any unilateral action risks backfiring,” said Gao Shiwang, a spokesperson for China’s Chamber of Commerce for Import and Export of Machinery and Electronic Products. He warned that further duties could harm US-China cooperation and destabilise the global semiconductor supply chain.

US imports of Chinese chips — primarily logic chips, LEDs and memory products — have already plummeted. Imports fell from US$3.88 billion in 2018 to US$2.09 billion in 2024, with China’s share of US chip imports shrinking from 10.3% to just 4.5%, the lowest level in a decade. Notably, much of the US imports come from multinational companies such as AMD, Intel, Micron and Samsung operating in China.

Facing US trade barriers, Chinese chipmakers are increasingly shifting exports to South Korea, Vietnam, India and Malaysia. Exports to India surged nearly 19-fold, from US$380 million in 2017 to US$7.46 billion in 2024. However, Trump’s reciprocal tariffs will also impact India, imposing a 26% duty.

Some Chinese chipmakers are moving production to Southeast Asia and Latin America to bypass restrictions. While Southeast Asia remains the primary destination, Latin America and Europe are emerging as future options. However, direct chip exports from China to the US are relatively small, as most Chinese chips are embedded into finished goods — which could be targeted in future actions.

In the auto sector, Trump’s administration recently raised tariffs but carved out exemptions for specific vehicles and parts. Mexico, the largest supplier of cars to the US, could be most affected. Roughly 23% of US vehicle imports come from Mexico, followed by 21% from the European Union (half from Germany), 18% from Japan, 17% from South Korea and 13% from Canada. Only 2% originate from China.

Chinese carmakers have minimal exposure to the US and Mexican markets. In 2024, US sales made up only 2% of Chinese car exports, while Mexico accounted for 6.9%, according to S&P Global Ratings. China exported 116,000 vehicles to the US in 2024, up from 75,000 two years earlier.

From 3 May, key auto parts — including engines, transmissions, lithium batteries and electrical components — will face a 25% tariff. The new tariffs will cover nearly 150 parts categories, from complex components to items such as tyres and brake hoses. Analysts warn that suppliers heavily exposed to the US market could suffer declining sales and margins.

Meanwhile, China’s battery industry is facing a major setback. New tariffs on Chinese lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles will rise to 70% after 3 May, compounding earlier increases imposed under President Biden. The US was China’s largest battery export market in 2024, accounting for 25% of all shipments.

Sun Yanran and Du Zhihang contributed to this report.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “In Depth: China’s Export Machine Stalls Under Trump’s New Trade Blitz” on 8 April. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)