China’s ‘involution’ could spur a post-capitalist era (Part 1)

EAI senior research fellow Lance Gore believes that Chinese official’s call to prevent “involution” highlights the severity of vicious competition among people, companies, localities and countries, which could lead to a transition to a post-capitalist society.

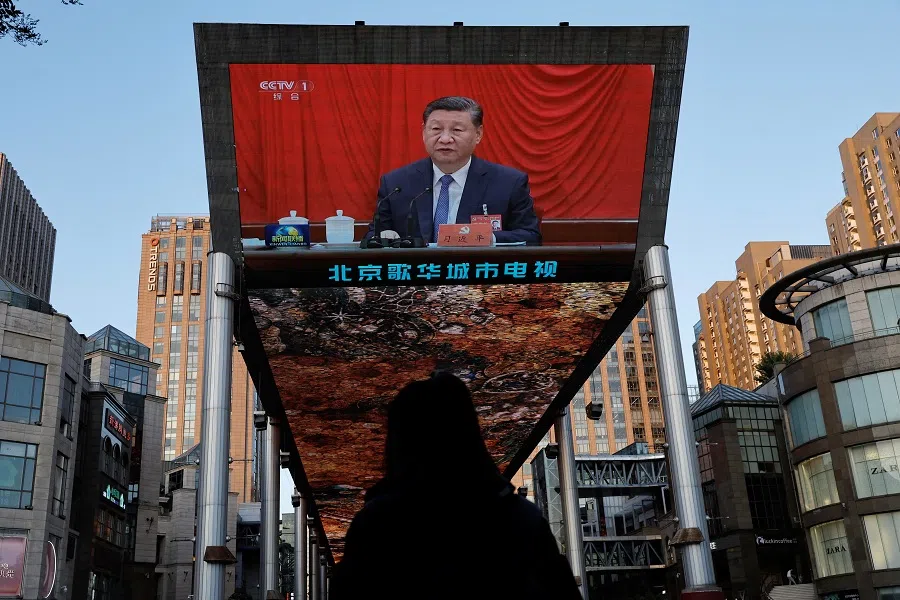

On 30 July, the Politburo of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee met for the first time after the third plenary session of the 20th Central Committee of the CCP, to set out the economic work for the second half of 2024.

The meeting called for the need to “prevent ‘involuted’ vicious competition”. This is the first time the term “involution” (内卷 or excessive competition) has appeared in the official language of the CCP’s highest echelons, and the underlying significance is extraordinary.

Amid the new technological revolution dominated by artificial intelligence (AI), intelligent automation, quantum computing and bioengineering, addressing this issue is crucial for the future of capitalism and will have significant historical impact.

This is no alarmist talk — while new technologies are expected to create abundant material wealth, involution creates fierce competition due to a lack of market demand. Overcoming this contradiction will inevitably lead to a full transition to post-capitalism.

Once-in-10,000-years upheaval

“Changes not seen in a century”, a familiar term for the people in China, describes what is currently happening in the world with all its turmoil and uncertainties over the future. From a longer historical perspective, these “changes” represent only a small fraction of a profound upheaval not witnessed in 10,000 years since the Agricultural Revolution.

... true scarcity will become a thing of the past. Instead, only temporary gaps in knowledge will remain.

The “once-in-10,000-years upheaval” far exceeds the scope of the “changes not seen in a century”, yet its direction is clear. By understanding the long-term big picture, one can navigate shorter-term changes effectively — just as the ancient sage Laozi put it, it is “like cooking a small fish”.

The hallmark of the new era is the irreversible, dramatic shift from scarcity to abundance. As productive forces advance to the atomic and molecular levels and converge with the exponential growth of the digital economy, near-zero marginal costs and the remarkable capabilities of AI, true scarcity will become a thing of the past. Instead, only temporary gaps in knowledge will remain.

The productive forces of the knowledge economy could potentially transform the conditions for all life forms in the biosphere, eliminating scarcity for them just as it could for humans.

OpenAI creator Sam Altman previously wrote about how the AI revolution will create phenomenal wealth. He suggests that once sufficiently powerful AI “joins the workforce”, the price of human labour, along with the costs of goods and services, will be driven towards zero. This poses a huge challenge to the way wealth is distributed.

I believe that the associated systemic changes will necessarily lead to the birth of a post-capitalist society.

Meanwhile, Altman argued that getting both production and distribution of wealth right will greatly improve people’s standard of living and enable more people to pursue the life they want. He also examined the above-outlined dramatic change in the context of the whole of human history, calling it the Fourth Revolution — i.e. the AI Revolution, which comes after the three major technological revolutions associated with agriculture, industry and computing. This reflects the overarching direction of these transformative changes.

The many forms of involution

Having said that, the present situation is getting worse, pushing the working populace into pitiful involution.

Involution has become a popular term in China in recent years, describing a range of negative realities: declining quality, efficiency and prices resulting from widespread vicious competition; a lack of prospects; and “meaningless efforts”, such as working excessively long hours for minimal wages.

In China, involution is especially brutal due to market, systemic and cultural factors, and it has significant economic, personal and international consequences.

It also refers to vicious or even malicious competition, a characteristic of capitalism. In China, involution is especially brutal due to market, systemic and cultural factors, and it has significant economic, personal and international consequences.

A race to the bottom for economic success

Economic involution, known in the West as the “race to the bottom”, refers to how companies, countries or localities compete with one another by excessively dialling down standards, wages, benefits, working conditions and environmental regulations, so as to increase the market share or attract investments through cost reduction. Price wars may lead to advanced production capacity being squeezed out by its backward rival.

In the case of some industries with strong agglomeration effects, industrial giants may take advantage of involution to secure a market monopoly, thereby harming market competition. Many enterprises are caught in a dilemma: either “mark down prices” or “pack up and go”.

The tailspinning markdowns among competitors cause companies to make only peanuts in profits or even suffer losses. This tends to seriously affect the healthy development of the whole industry in question, because sustainable development is ensured only when enterprises make profits and enough of it to invest in subsequent research and development.

Involution in China is accelerated by systemic factors and is closely linked to local industrial isomorphism — where industries become homogenised — and market fragmentation.

In their efforts to attract investments and businesses, many local governments overlook their own resource endowments and industrial foundations. They often provide excessively generous incentives that do not align with local conditions, aiming to develop emerging industries. This leads to industrial isomorphism and duplicated construction projects.

Another factor contributing to involution is local protectionism. In some areas, artificial market barriers create fragmentation, preventing industries from achieving economies of scale. The business culture, characterised by adages like “the commercial arena is like a battlefield” and a cutthroat mentality of making opponents “bleed out the last drop of blood”, leads to ruthless competition. As a result, no one benefits, and the outcome is often a chaotic and destructive struggle.

Some counteractive ideas have already been put forth in the third plenary session. The Committee has resolved to “review and abolish regulations and practices that impede the development of a unified national market and fair competition”, and to “strictly prohibit policy incentives in breach of laws and regulations”.

While these policies can help to counter industrial involution and vicious competition, they are not able to change the essential nature of capital, and the necessary institutional reforms are still missing.

The recent Politburo meeting also highlighted the need to “strengthen the market’s ‘survival-of-the-fittest’ mechanism and smooth the exit channels for backward and inefficient production capacity”.

While these policies can help to counter industrial involution and vicious competition, they are not able to change the essential nature of capital, and the necessary institutional reforms are still missing.

For government officials at all levels, implementing these reforms can be problematic. Many unviable enterprises would close, leading to a rise in unemployment, and past mistakes by previous leaders would be exposed. As a result, officials often choose to maintain the status quo and just muddle on.

Who wants to be ‘Involution King’?

The ills of involution are mainly felt on the personal level, referred to by the Western capitalist countries as the “rat race”. The metaphor points to stressful and often meaningless competition for material gains.

To run in the race usually means being trapped in a monotonous, repetitive and high-pressure work style, with almost no time for leisure or personal fulfilment; yet one feels obliged to keep at it because of financial pressure or social expectations.

Young people caught in such a race often experience profound fatigue and powerlessness. They feel they are endlessly giving without seeing any meaningful progress or hope for a breakthrough.

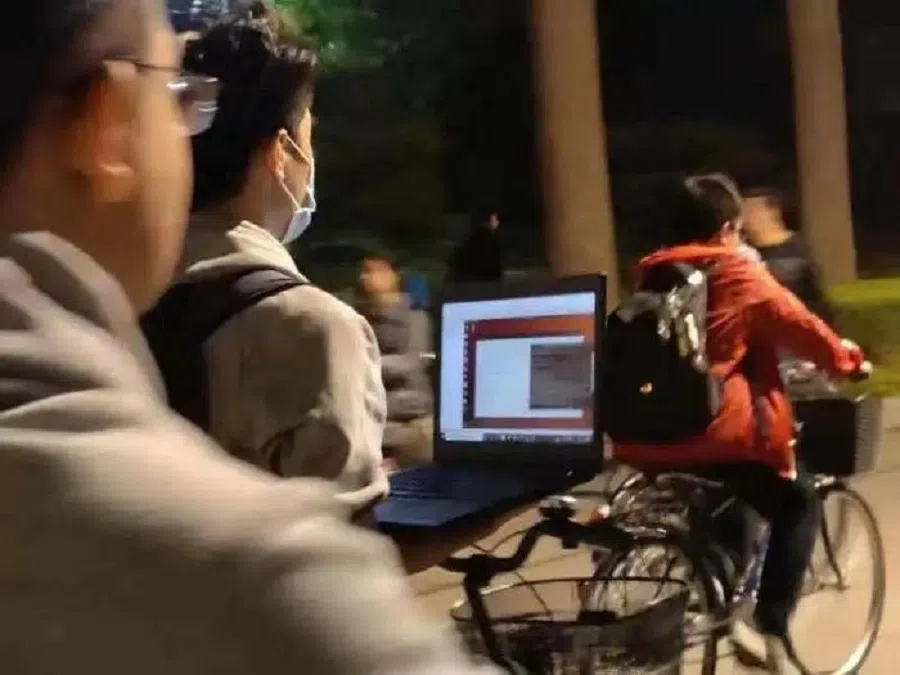

In today’s Chinese society, it has become fashionable for youths to say: “That’s too involuted.” After a photo of a Tsinghua University student juggling his open laptop while cycling was widely circulated, the student became known as the “Involuted King”.

From preschool or even as early as “prenatal education”, children are immersed in the relentless cycle of involution typical of the adult world. Despite the Chinese government’s strong crackdown on the after-school tutoring industry and the implementation of relevant laws, these measures have proven largely ineffective over time. Training courses have either gone underground or become decentralised, much like underground house churches.

While China’s per capita GDP is already over US$12,000, as many as 600 million of its people live on a monthly income of merely 1,000 RMB (USD$140). One major reason is involution in the employment arena.

In the US, where welfare is not as favourable as in European countries, involution has given rise to a class of the “working poor”. These people work hard, sometimes at several jobs, and still struggle to support their families. Homelessness in cities around America is a shame for advanced capitalism and a mockery of social justice.

I clearly remember during my time in the US as a graduate student, how the secretaries in my department would often complain that their monthly salaries would not be enough if they bought lunch. When a bank introduced a US$5 monthly account maintenance fee, it became the last straw for many struggling individuals. One college student, outraged by this move, launched a public campaign to force the bank to reverse its decision.

Indeed, the “rat race” is supposed to signify meaningless toil. And since it is meaningless, why toil any longer?

The widespread pressure to improve financial performance statements ensures that such incidents are likely to continue. For example, by manipulating numbers in labour processes controlled by algorithms, Chinese platform companies can push couriers to their breaking point. As the cost of living rises, the phenomenon of the “working poor” threatens to spread in China.

From ‘involution’ to ‘lying flat’

The personal consequences of involution are twofold. Firstly, there is the rise of the “lying flat” (躺平) philosophy and lifestyle. After the term “involution” gained traction, its antonym, “lying flat” rose to prominence and took discussion to the next stage.

A blogger known as “Kind Traveller” proudly shared: “I haven’t worked in over two years. I’ve spent this time enjoying myself and don’t see anything wrong with it. The pressure mainly comes from comparisons with others and traditional expectations from elders. There’s no need to live according to their standards.”

He even waxed philosophical: “Lying flat is my sapiential movement. Only in lying flat is Man alone the measure of all things.”

Indeed, the “rat race” is supposed to signify meaningless toil. And since it is meaningless, why toil any longer?

The idea that “only in lying flat is Man alone the measure of all things” alludes to the fact that the Chinese economy is not yet “people-centred” as claimed in the official propaganda. Capitalism has always been about “money as substance, people as utilities”.

Hatred for capital: A class struggle?

This brings us to the second consequence of involution: hatred for capital. Chinese youths are increasingly antagonistic towards capital. They are particularly repulsed by the lofty “exhortations” of the “capitalists”, such as “all of your distress and confusion come from having too much desire and making too little effort”, or Jack Ma’s glorification of the “996” work culture (9am to 9pm, six days a week).

Such hatred finds an immediate outlet and theoretical basis in the official ideology, which seeks to resist “exploitation and oppression” through “class struggle”. As Mao Zedong put it so illuminatingly and powerfully, “The numerous tenets of Marxism are summed up in just one statement: rebellion is justified.”

Thanks to the AI revolution, it is entirely conceivable for China to beat all its competitors and become the world’s sole producer and supplier, with enough output to satisfy the demands of the entire world and more.

This is precisely what the authorities fear most. Unable to counter the dissatisfaction within the bounds of ideological orthodoxy, they resort to reintroducing the slogan of “common prosperity”.

However, pursuing common prosperity within a capitalist framework is inherently flawed. This situation highlights that the official ideology is either outdated or lacking in innovation. Despite the official goal of “striving for a good and beautiful life” as desired by the people, it is evident that involution is not what they want.

Involution goes international

The consequences of involution on external relations are becoming increasingly apparent, as highlighted by the recent “overcapacity” tug-of-war between China and the US.

Many of China’s exports have become dirt-cheap due to involution, resulting in a tremendous waste of resources, ecological damage and economic losses. Overcapacity is a major reason why Chinese enterprises are locked in vicious competition. To find a way out, they actively dump their outputs abroad, setting off alarm bells across the globe.

Trade barriers are being erected all over the West to block the onslaught of Chinese goods. Under the pretext of ensuring supply chain security, Chinese products are discriminated against.

Thus, China has shifted its focus to the global south, where it remains invincible. As The Economist aptly summarised in its 1 August article, “Chinese Companies Are Winning the Global South”.

Thanks to the AI revolution, it is entirely conceivable for China to beat all its competitors and become the world’s sole producer and supplier, with enough output to satisfy the demands of the entire world and more. This hypothetical scenario would see two outcomes: one, China’s total isolation and being made an enemy of the world; two, the total bankruptcy of the capitalist mode of production, prompting the world to work together to create a post-capitalist order.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “中共政治局首提“内卷”背后(上)”.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)