The SCO development bank: China’s answer to Western financial hegemony?

China’s push for an SCO development bank aims to offer Eurasia a non-dollar, low-conditionality alternative to Western finance. But governance challenges, funding gaps and divergent interests may stall its ambition before it takes flight. Researcher Genevieve Donnellon-May discusses the issue.

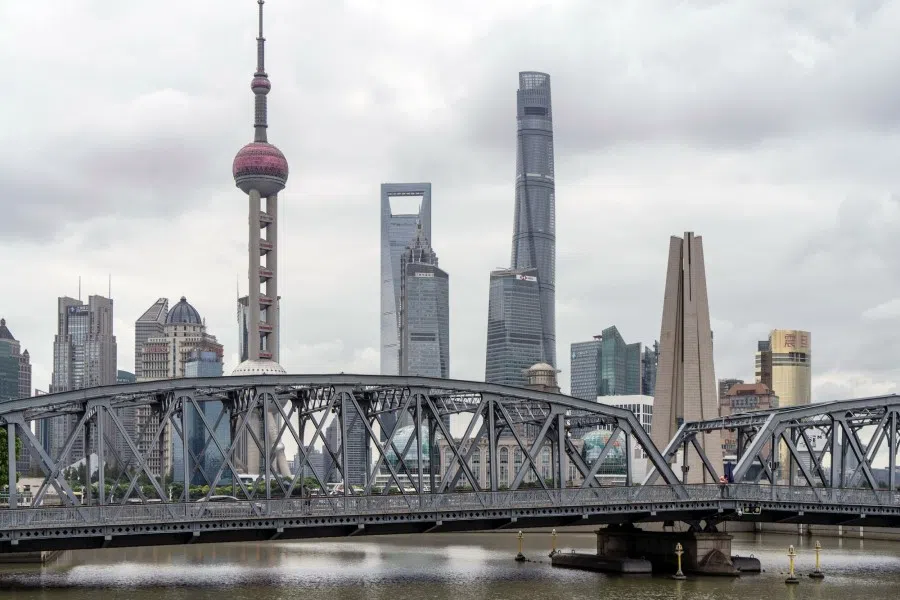

At the recent 25th Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) Summit held in Tianjin, China, Chinese President Xi Jinping renewed Beijing’s longstanding call for an SCO development bank. He pledged two billion RMB (around US$280 million) in grants to member states and ten billion RMB in loans to the SCO Interbank Consortium (SCO IBC) over the next three years, underscoring China’s push to institutionalise financial cooperation within the bloc.

President Xi emphasised that the bank “should be established as soon as possible to provide stronger support for the security and economic cooperation of member states”. A subsequent statement confirmed that the SCO had “decided to establish a development bank and accelerate consultations on a series of issues related to the financial institution’s operation”.

Global South’s financial future?

Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi noted that the new bank will boost infrastructure development and socioeconomic progress among SCO countries. He did not provide a timeline.

Shortly after President Xi’s announcement, Russian state media TASS highlighted the SCO member states’ support for reforms in international financial governance aimed at increasing the role of developing countries in Western-led institutions and promoting economic growth, including the gradual expansion of using national currencies in mutual settlements.

The initiative faced resistance, particularly from Russia, which preferred to expand its influence via the Eurasian Development Bank, where its influence outweighs Beijing’s.

At the time of writing, full details on the bank remain limited.

Founded in 2001 as a security-focused bloc among China, Russia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, the SCO has since expanded to ten full members — including India, Pakistan, Iran, Uzbekistan and Belarus — and engages over a dozen dialogue partners like Saudi Arabia and Turkey.

At present, the organisation spans much of Eurasia and the Global South, covering major and emerging economies alongside resource-rich states. It additionally ranks among the world’s largest regional organisations by geographic scope and population.

History, features and objectives of the new bank

Following early discussions of joint project funding through the Interbank SCO Council in 2005, China formally proposed an SCO development bank in 2010 to promote regional trade using local currencies. The initiative faced resistance, particularly from Russia, which preferred to expand its influence via the Eurasian Development Bank, where its influence outweighs Beijing’s.

Calls for a dedicated SCO bank resurfaced at the 2019 summit, when then-Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan urged the establishment of both a development bank and an SCO development fund. But recent geopolitical shifts, alongside statements from Vice-Premier Ding Xuexiang earlier this year, indicate growing momentum, culminating in President Xi Jinping’s announcement at the Tianjin summit.

... the SCO development bank could emerge as both the first non-dollar-denominated multilateral development bank and a “security-focused” development finance institution.

Three main reasons are likely to be behind the announcement and the bank’s establishment:

(1) consolidating China-led financial networks across Eurasia by supporting regional development agendas (such as transport and energy corridors), and promoting policy coordination;

(2) providing members with access to capital outside Western-dominated systems and reducing their exposure to unilateral US measures amid tensions with the US; and

(3) advancing an alternative economic order aligned with SCO principles of multipolarity and non-interference, potentially positioning China as the architect of a parallel regional financial mechanism. In this context, the SCO development bank could emerge as both the first non-dollar-denominated multilateral development bank and a “security-focused” development finance institution.

Placing development finance within the SCO framework would extend this approach into a politically and security-linked multilateral context, reinforcing bloc cohesion, projecting a multipolar narrative, while also supporting concomitant efforts to internationalise the RMB.

Dual role: finance and politics

The establishment of an SCO development bank could reshape Asia’s financial architecture by providing member-states an alternative to International Monetary Fund or World Bank financing, which often carries political and/or economic conditionalities. By offering flexible, rapid-response funding tailored to member priorities, the bank could strengthen the SCO’s dual political and financial role.

Anchoring financial cooperation within the SCO could help China promote a state-led, low-conditionality development model.

The new development bank benefits all parties. For SCO members, it could complement or compete against other sources of funding, while also diversifying available development finance. For Beijing, this aligns with its broader strategy of building governance financial institutions (like the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the BRICS New Development Bank, NDB), which expand China’s influence and offer alternatives or even complement Western-led structures.

There is a clear need for it. Infrastructure demand in the SCO region remains high. Central Asia, for example, faces persistent connectivity gaps, with roughly half its population lacking reliable internet access. Financing for broadband, transport corridors, energy pipelines, and renewable power projects would address these urgent development needs while deepening regional integration.

With Beijing already advancing these objectives through initiatives like the Belt and Road Initiative, an SCO bank could help institutionalise and coordinate these efforts, which are further supported by other initiatives such as the three new China-SCO cooperation centres — each focusing on innovation, education or sustainable development.

Geopolitically and geoeconomically, the bank could enhance Beijing’s influence. Anchoring financial cooperation within the SCO could help China promote a state-led, low-conditionality development model. For sanctioned states such as Russia and Iran, it could provide a multilateral institution that conveys legitimacy and reduces the appearance of direct bilateral evasion, while mitigating risks associated with US-dominated financial systems.

Building on existing trade ties — China’s annual bilateral trade with other SCO member states having already surpassed US$500 billion, facilitating trade and financing in local currencies would further insulate SCO members from dollar-related risks and accelerate financial multipolarity.

Foremost is institutional capacity: establishing a credible bank requires robust governance, transparent risk management and strong regulatory oversight.

Challenges ahead

The SCO development bank faces major hurdles. Foremost is institutional capacity: establishing a credible bank requires robust governance, transparent risk management and strong regulatory oversight. Without these, inefficiency or politicisation could undermine confidence among members and borrowers — a concern already seen with the China-led NDB, which faces criticism for limited transparency, weak accountability mechanisms, and slow project implementation.

Financing sustainability is another concern. Regional infrastructure needs far exceed China’s pledged ten billion RMB; smaller members are unlikely to contribute substantial capital, creating a risk of overreliance on Beijing and perceptions of unilateral control.

Divergent interests alongside internal dynamics could also complicate governance, project selection, and decision-making. While shared priorities, such as multipolarity and common grievances with the US, provide some alignment, balancing competing agendas across countries with different economic sizes, development priorities, and population growth and (strategic) rivalries, is essential to ensure the bank functions equitably.

The SCO’s historical record of limited effectiveness underscores the challenge of translating ambition into operational reality. Overcoming these hurdles will be critical for the SCO bank to move beyond rhetoric and emerge as a credible development institution.

The SCO development bank signals China’s ambition to transform the bloc into a political and financial actor, offering an alternative development finance model while advancing a multipolar economic order. Its success, however, will depend on how well it navigates governance, financing, internal dynamics and differing interests.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)