[Photos] From poverty to prosperity: A century of social transformation in Singapore

Although Singapore’s history has been extensively documented, the experiences of impoverished communities are often forgotten. In his new historical picture book, historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao looks at the process of nation building from the perspective of the poor, emphasising the spiritual and social forces that shaped Singapore’s transformation.

(All photographs courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao.)

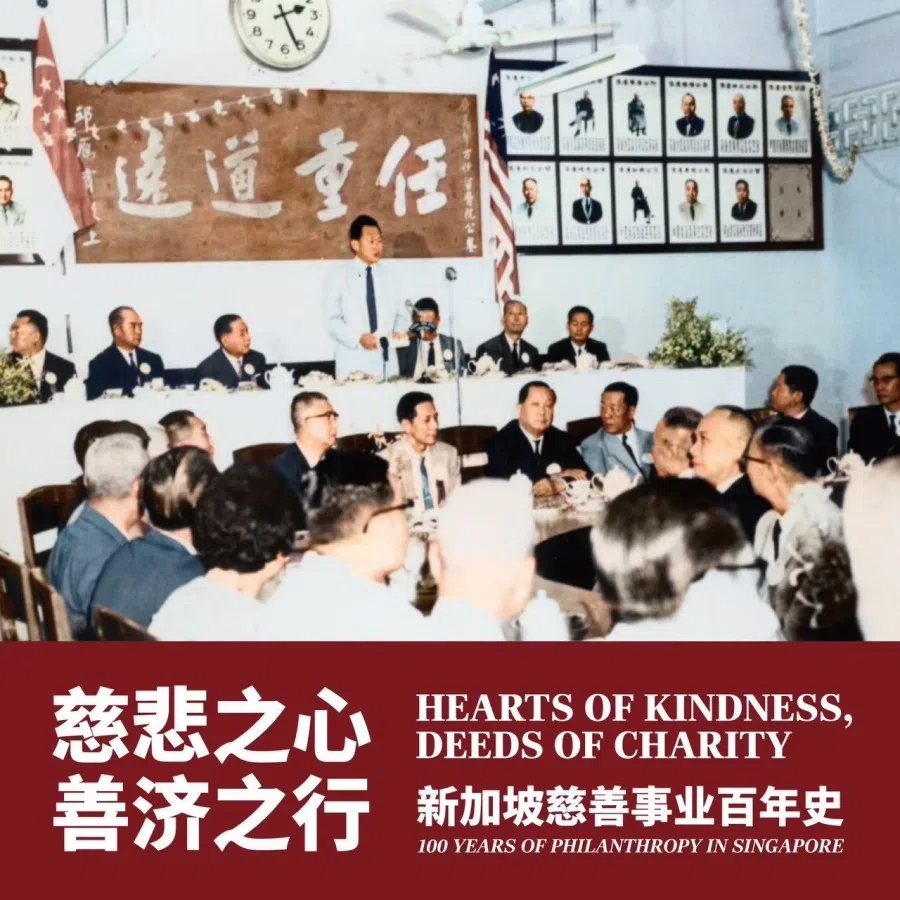

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the founding of the Republic of Singapore. Over the past five years, I have published four illustrated books on Singapore history. This year, at the invitation of Sian Chay Medical Institution’s executive chairman Toh Soon Huat, I have published a new historical picture book, Hearts of Kindness, Deeds of Charity — 100 Years of Philanthropy in Singapore, a project that took two years to complete.

Unlike my previous works, this volume focuses more on the hardships faced by the lower strata of Singapore society in the early years, and on how various sectors extended helping hands and worked together to address these difficulties. Their efforts not only improved people’s livelihoods and the quality of the community environment, but, more importantly, fostered a sense of community identity that became the foundation of a shared national spirit. The process of compiling this book was also a journey of learning about Singapore’s history of struggle, from which I gained many new insights.

Singapore’s journey from poverty to becoming a prosperous society followed two parallel paths: one material, the other spiritual. The two are interdependent. Material development follows economic principles, while the spiritual path is more complex — fundamentally a process of cultural self-selection and adaptation. Because much of this lies in the abstract realm, it is not easily perceived, and therefore rarely receives detailed analysis.

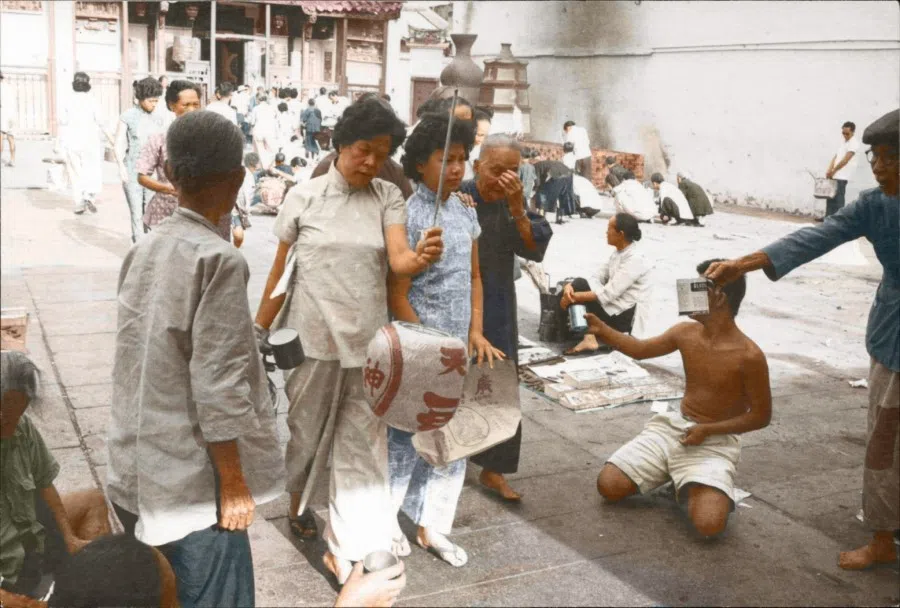

The flip side of prosperity was disorder and grime, even in the heart of the city. The colonial government did very little to address these problems.

Asymmetrical colonial development

In the old days, Singapore was a largely untouched island covered in dense tropical jungles, with Malay fishing villages scattered along its shores. The arrival of Raffles in 1819 marked the beginning of Singapore’s modern development. As Western colonialism reached its height in Asia during the 19th century, colonial powers brought in large numbers of Chinese and Indian labourers to work in rubber plantations, tin mines and other industries across the Malay peninsula and the Indonesian archipelago. Singapore became a hub for shipping, finance, commerce and tourism.

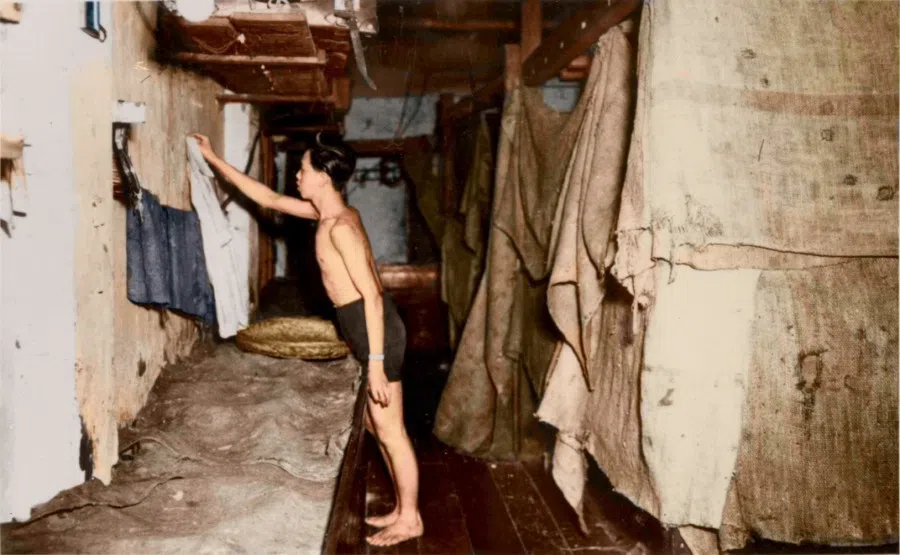

Despite commercial prosperity, the colonial government’s main goal was profit. It had no concept of a modern welfare state. Workers and farmers lived under severe exploitation, impoverished and confined to cramped, dirty living conditions. Urban development reflected the same pattern. Apart from the colonial town along the Singapore River, with its grand municipal buildings, customs house, government offices and neatly planned streets, most other areas were chaotic and squalid.

Poor sanitation gave rise to various diseases. Even the Singapore River in the city centre was filthy; older generations of Singaporeans remember the river’s foul stench. The flip side of prosperity was disorder and grime, even in the heart of the city. The colonial government did very little to address these problems.

... the responsibility of caring for the poor fell largely on religious organisations and clan associations. They established charitable initiatives to provide food, clothing and basic necessities, and offered relief during fires, floods and other disasters.

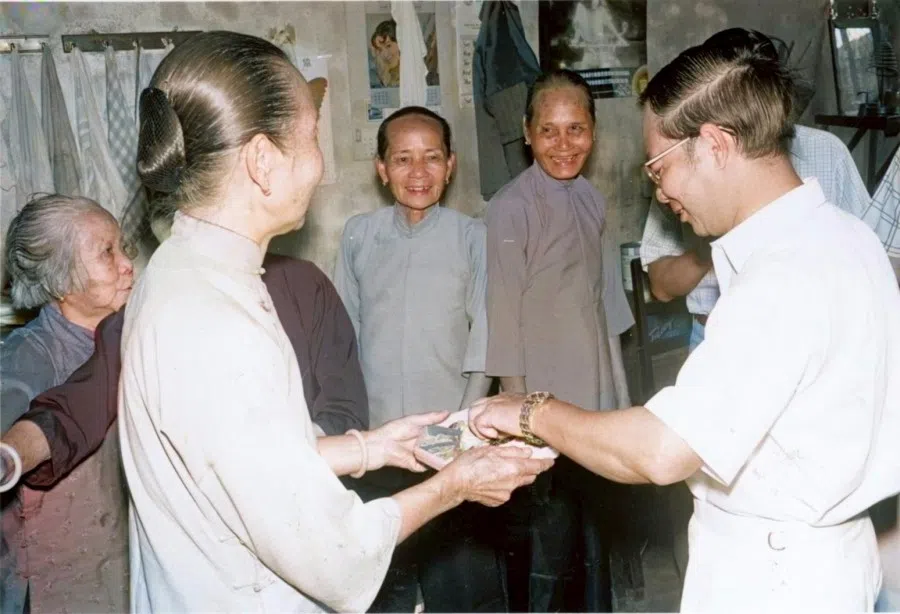

As a result, the responsibility of caring for the poor fell largely on religious organisations and clan associations. They established charitable initiatives to provide food, clothing and basic necessities, and offered relief during fires, floods and other disasters. Because the colonial government did not prioritise the welfare of the wider population, grassroots community cohesion became particularly strong, shaping the early sense of community in Singapore.

Nevertheless, no matter how widespread charitable work was, it could never fully meet the basic needs of ordinary people, such as public infrastructure, medical services and educational facilities that improve health and quality of life. These are social development measures that only a government, through its public authority, can implement effectively. It was only after the Republic of Singapore was established in 1965 that such measures could be generally implemented.

... genuine charity is not merely about providing relief to the poor, but also about targeting the root causes of poverty, such as the lack of education, knowledge and opportunities for advancement.

Postwar and postcolonial unrest

After World War II, people across the world had to rebuild their homes from the ruins of war. Living conditions in post-war Singapore were extremely harsh. Before Japan’s defeat, the Japanese military administration issued “banana money”, printing it without restraint and forcibly extracting wealth from the population. When the war ended, this currency became worthless overnight. People were left destitute, facing severe hyperinflation.

At the same time, colonial subjects were resisting their former imperial rulers and searching for new identities. These interacting factors — political unrest, social anxiety, frequent strikes, student boycotts and racial riots — stalled economic development and created fertile ground for communist ideology.

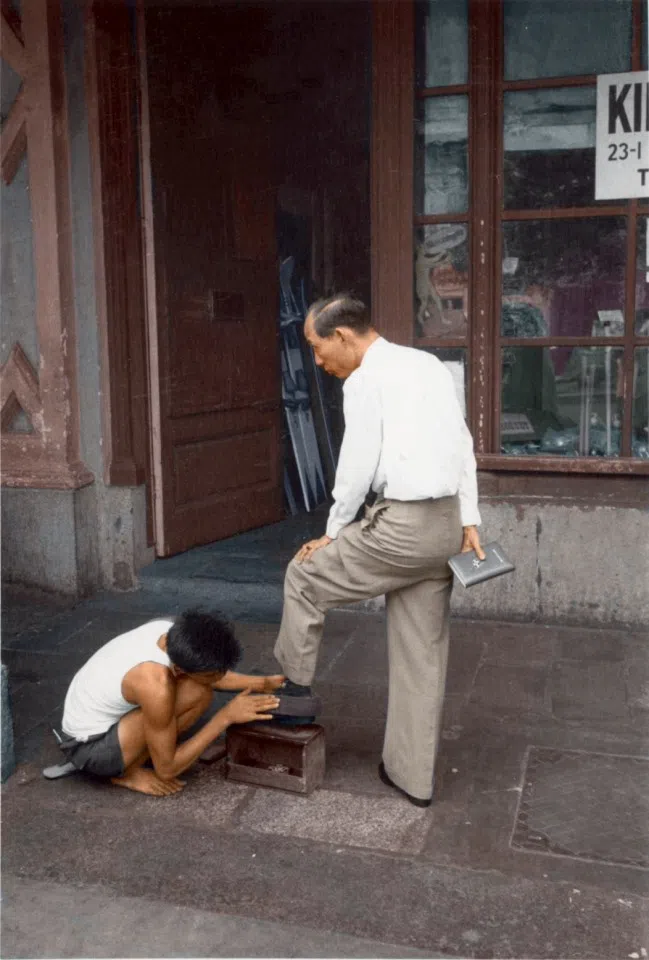

In those years, it was common to see panhandlers, shoeshine boys and elderly women sewing clothes for others along the alleys outside temples. In such circumstances, traditional clan associations and community organisations became the most powerful providers of relief.

In 1959, Singapore became a self-governing state. In 1963, it joined Malaysia, and in 1965, it became an independent nation. Throughout this period, society remained unsettled. Only after independence could the government consolidate power and resources, allowing large-scale and effective development to truly begin.

It is important to emphasise that genuine charity is not merely about providing relief to the poor, but also about targeting the root causes of poverty, such as the lack of education, knowledge and opportunities for advancement. Therefore, universal education, improved public facilities and expanded economic opportunities are the fundamental ways to eradicate poverty.

This was the prerequisite for building vast numbers of affordable public housing units — in order for everyone to be able to buy a home, land ownership must first be equalised.

Laying the foundation of a more equitable society

Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew’s policy objectives were extremely clear: to create a fair environment for development by providing adequate education, housing and employment opportunities. This meant nurturing the younger generation while also making up for the opportunities that earlier generations had lacked.

Through legislation, the Singapore government placed large amounts of land under public ownership to ensure that land resources could be distributed equitably. This was the prerequisite for building vast numbers of affordable public housing units — in order for everyone to be able to buy a home, land ownership must first be equalised.

As for improving living conditions, this involved numerous details: maternal and child welfare, community literacy classes, mobile clinics and libraries, and many other initiatives.

There is one aspect that had a profoundly far-reaching impact, though it is not always fully recognised: encouraging the public to improve their community environment with their own hands. Lee Kuan Yew mobilised citizens to clean up their living surroundings, and a strong sense of community identity was forged through this process.

Children who grow up in such environments are not only physically weaker and more prone to illness; they also easily develop feelings of inferiority when they compare their surroundings with the clean and beautiful neighbourhoods of the wealthy.

Mitigating the physical and psychological impacts of poverty

Poverty has two harmful consequences: material deprivation and psychological impoverishment. The latter is often overlooked. In many countries, the disparity between public facilities in wealthy neighbourhoods and those in poor neighbourhoods is extremely stark.

Wealthy communities tend to have clean and orderly roads, well-designed parking areas, gardens with lush greenery, and attractive street lighting. Poor communities, by contrast, are the opposite: broken and damaged streets, street lamps that have long been left unrepaired, drains clogged with filth, rusty playground equipment in the parks, and so on.

Children who grow up in such environments are not only physically weaker and more prone to illness; they also easily develop feelings of inferiority when they compare their surroundings with the clean and beautiful neighbourhoods of the wealthy. Moreover, because many parents in such communities have not received higher education and have little time to supervise them, these children tend to roam the streets after school, fall in with bad company, pick up bad habits or join delinquent gangs in search of belonging. Such an environment becomes a breeding ground for poverty and crime, and this cycle can be passed down from generation to generation.

Therefore, by providing high-quality public facilities and services across affluent, middle-income and lower-income neighbourhoods, the government eliminated the sense of inferiority among children from poorer families. Well-built roads, parks and green spaces, bus stops, car parks, and markets became tools of social equalisation. Moreover, community leaders encouraged residents to use their own hands to improve their surroundings — an effective means of enhancing the psychological well-being of lower-income groups.

In this regard, the Lee Kuan Yew government performed exceptionally well. Of course, it cannot be denied that Singapore’s small land area makes such efforts technically easier. Yet even among other small countries, very few have achieved what Singapore has accomplished.

As most of the population gradually moved into high-rise public housing, the close-knit neighbourly bonds and strong sense of human warmth found in traditional communities slowly diminished.

The next chapter in the Singapore success story

On the other hand, every era brings its own challenges, and every step forward also creates new problems. As most of the population gradually moved into high-rise public housing, the close-knit neighbourly bonds and strong sense of human warmth found in traditional communities slowly diminished. People became wealthier, but this did not necessarily mean they became more emotionally connected to one another.

Furthermore, the younger generation has no memory of Singapore’s hardship years, and may therefore take for granted what they have today. Their sense of appreciation may not be as strong, and their drive to struggle and strive may not match that of the previous generation, simply because they already possess much of what earlier generations lacked. This can, in turn, weaken society’s sense of responsibility. These are challenges Singapore will inevitably face.

In any case, while editing this picture book, I felt as though I had personally taken a journey through Singapore’s history, especially into the lives of the lower-income communities. I learned how people in the early years lived, how they improved their living conditions with their own hands, and how this changed their destinies. This understanding and insight has become the greatest spiritual reward of the entire experience.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)