[Photos] Returning Zhu Feng: The long journey of a CCP secret agent’s remains

In the years after the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) came to power in mainland China, the Kuomintang (KMT) launched an extensive political purge in Taiwan that became known as the White Terror. The KMT hunted down and executed dissenters, including CCP spies, in an attempt to consolidate power. Today, the stories of the White Terror’s victims are slowly emerging. Taiwanese historical photo collector Hsu Chung-mao, who played a significant role in uncovering these forgotten experiences, tells us more about the dark chapter of Taiwan’s history.

(All photographs courtesy of Hsu Chung-mao.)

The story of Wu Shi — the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s “Secret Envoy No. 1” in Taiwan — was recently adapted into a mainland Chinese television drama called Silent Honour. The hugely popular show has attracted widespread attention, and has been accompanied by numerous write-ups and commentaries across various media platforms.

Recording the voices of CCP agents

I cannot help but recall that I was the first to introduce this chapter of history in the mainland back in 2001, through the popular magazine Old Photographs. Subsequently, in 2005, I presented a comprehensive account of this story in Asia Weekly, which was then reproduced in full by Reference News (参考消息) in mainland China, sparking a wave of media coverage across the mainland. By 2013, giant statues of intelligence agents Wu Shi, Zhu Feng, Chen Baocang and Nie Xi had been erected in Beijing’s Western Hills. Today, the story has finally been adapted into the hit television series Silent Honour — a process that has taken 24 years.

Objectively, one might say I initiated this journey of historical exploration. I interviewed many individuals who were directly involved with Zhu Feng at the time, not only preserving their oral histories but also gaining a more vivid grasp of the historical circumstances through their recollections. Today, all of them have passed away. What I write in this article is therefore primarily my own emotional understanding of that history. It is not rigid documentary material, but the lives, breath and souls of real people.

Uncovering lost stories of White Terror in Taiwan

In 1999, while editing a pictorial volume on Taiwan’s history, I discovered a batch of photographs in a newspaper archive showing CCP agents being executed. I felt deeply drawn to them, and began organising and researching the material.

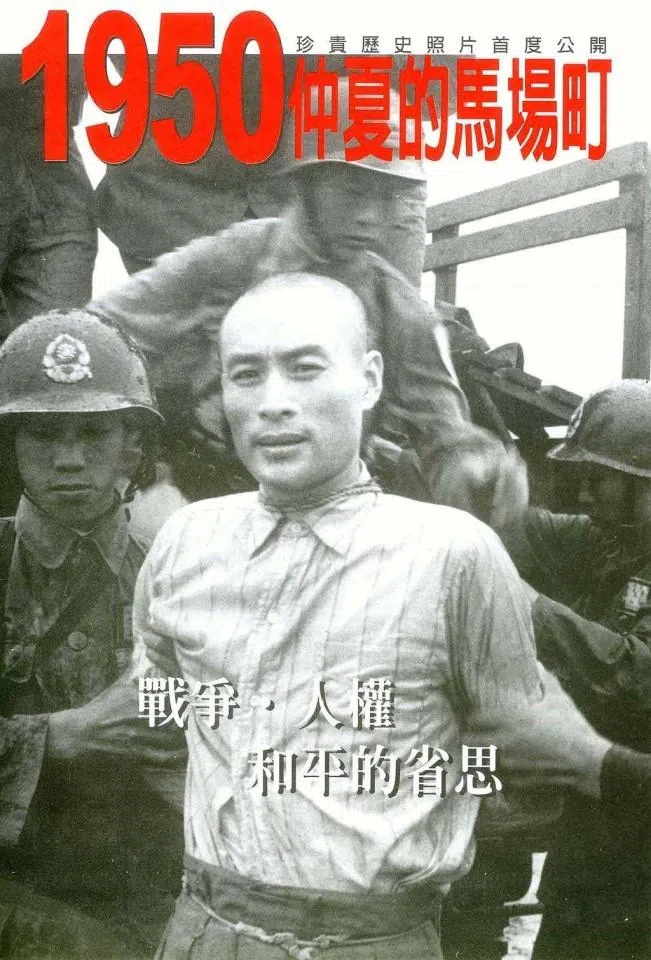

In September the following year, with the support of Lung Ying-tai (then the director of Taipei City’s Cultural Bureau), I held a special exhibition titled Midsummer 1950 at Machangding (1950仲夏马场町) at Taipei’s 228 Memorial Museum. The exhibition presented well-known political cases from the White Terror period, including the Wu Shi case. At the time, cross-strait exchanges were still limited, and the event did not attract much attention from the mainland.

... the exhibition carried profound significance for its era. It marked the first time the Kuomintang (KMT) rationally confronted the grievances of the Chinese Civil War, signalling a willingness to extend a hand of reconciliation to the CCP.

Nevertheless, the exhibition carried profound significance for its era. It marked the first time the Kuomintang (KMT) rationally confronted the grievances of the Chinese Civil War, signalling a willingness to extend a hand of reconciliation to the CCP. It acknowledged that the mutual killings of the past were detrimental to national unity and cross-strait peace, and expressed a readiness to confront history honestly in order to build a new relationship grounded in national reconciliation.

Then Taipei mayor Ma Ying-jeou and Lung Ying-tai accepted my proposal to hold this landmark exhibition, which laid an important spiritual foundation for the rapid move toward reconciliation and peace in cross-strait relations after Ma assumed office as president eight years later.

Zhu Feng’s story

The following year, I published a long illustrated feature in Old Photographs, titled “The War After the War”, recounting the past of Wu Shi and Zhu Feng. Surprisingly, the article caught the attention of Zhu Feng’s daughter, Zhu Xiaofeng, who wrote a letter to the editorial office of Old Photographs.

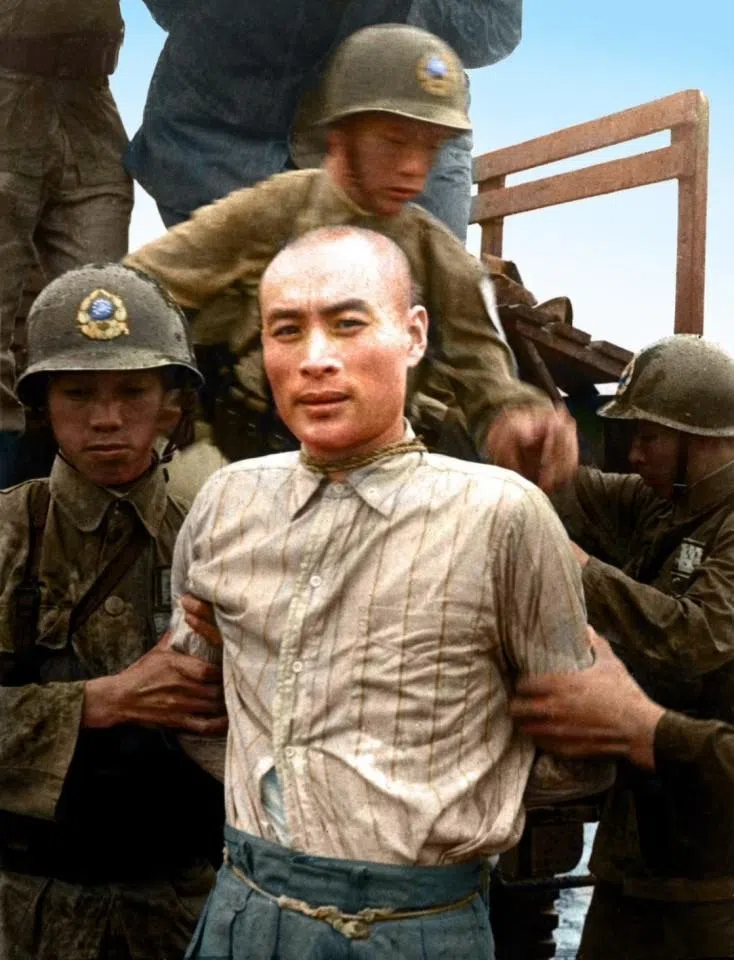

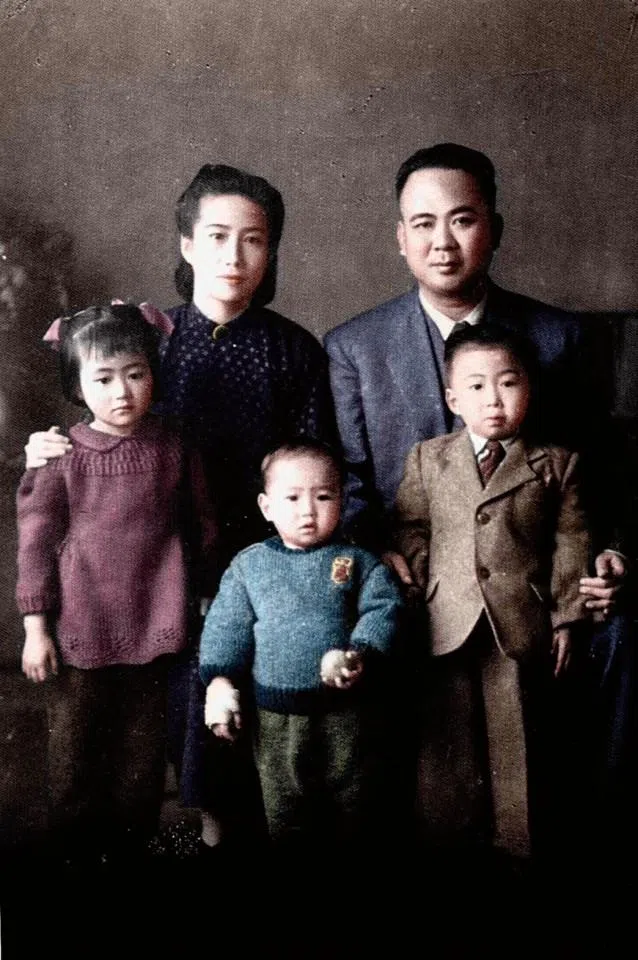

“A year ago, I saw a photograph in Issue No. 16 of Old Photographs, published by Shandong Pictorial Press. The photo faithfully recorded the scene of my mother Zhu Feng being tried in Taiwan before her execution in 1950. This was the first time in 50 years that I had seen the situation as it truly was (no such materials had ever existed before), and I was overwhelmed with emotion. No words could express how I felt at that moment.

“In the photograph, my mother is wearing a small floral qipao that she often liked to wear at home in Shanghai, with a woollen vest over it. Her face is still as gaunt as ever, her figure still so familiar — it felt as though I had returned to 50 years ago.” — Zhu Xiaofeng, Zhu Feng’s daughter

“In the photograph, my mother is wearing a small floral qipao that she often liked to wear at home in Shanghai, with a woollen vest over it. Her face is still as gaunt as ever, her figure still so familiar — it felt as though I had returned to 50 years ago. In the photograph, although she was facing death, surrounded by judges and military police as ferocious as tigers and leopards, she remained remarkably calm and composed, showing no fear, just as she had when confronting the hardships of life.

“… She had long been engaged in underground work that constantly put her life in danger. She was arrested twice and subjected to brutal torture, which left her thumb permanently injured, yet her faith never wavered. In the end, she was unfortunately captured while carrying out her mission. Before being executed, she shouted ‘Long live the Communist Party!’ expressing her unwavering conviction and her great moral courage.

A martyr who sacrificed everything for the greater good

“My mother was also a human being with flesh and blood, and deep emotions. In her work, she understood the larger picture, put collective interests first, struggled tirelessly, treated comrades as ‘elder sisters’, and was always willing to help others. She was also profoundly affectionate towards her family and children. When the nationwide liberation of the mainland was imminent and she was about to leave for Taiwan on assignment, she wrote in her letters of her longing to reunite with her family, lamenting that ‘people are not made of grass or wood.’

“In the three letters she wrote to me, the first asked me to send her photographs of myself (because of her work, she had not seen me for several years); the second urged me to come to Guangzhou soon and wait for her to arrive from Hong Kong so that we could meet (but Shanghai had just been liberated and I was still in school — how could that have been easy?); in the third letter, she was already preparing to depart for Taiwan and wrote that personal matters would have to be set aside for the time being. In the end, none of these wishes were fulfilled.

“My mother was deeply emotional, yet she was able to sacrifice everything personal for the cause. Her calm composure in the photograph shows that she had already accepted death without fear, firmly believing that the cause of national liberation and reunification for which she struggled and ultimately sacrificed would surely succeed, and that her family and children would understand her choice.

“My mother was martyred in 1950, when the mainland had already been liberated. Fifty-two years have now passed. She never enjoyed even a single day of the freedom and happiness of post-liberation life, nor did she live to see a reunion with her family.”

The journey to recover Zhu Feng’s remains

One year after the article in Old Photographs, in 2002 I published a more detailed account of the historical facts in Phoenix Weekly, framing it as an opportunity for Chinese people to reflect on their own history. The response from readers was strong. Not long afterward, Zhu Xiaofeng sent me a letter via Phoenix Weekly, thanking me for providing detailed reporting and rare photographs concerning her mother, Zhu Feng, during her time in Taiwan. She also asked whether I could help trace the whereabouts of her mother’s remains. After a family discussion, the Zhu family hoped to bring her remains back to the mainland.

Through Old Photographs and Phoenix Weekly, Zhu Xiaofeng was able to get in touch with me. We also spoke briefly by phone. I sensed that this long-dormant case might become an emotionally overwhelming task for me to bear.

During the Spring Festival of 2003, I took my entire family to the mainland. At the time, my daughter Danyu was ten years old and Danhan was five. We stayed at the Peace Hotel on the Bund in Shanghai. While my children were still young, I made a point of taking them to the mainland whenever possible, not only for family bonding, but also to leave them with warm and lasting memories, which would help them develop an emotional connection with China from an early age. As a result, they travelled to the mainland many times with us during their childhood.

Because this was such a painful chapter of her life, Zhu Xiaofeng’s expression was grave. She conveyed her earnest hope that I could help locate her mother’s remains.

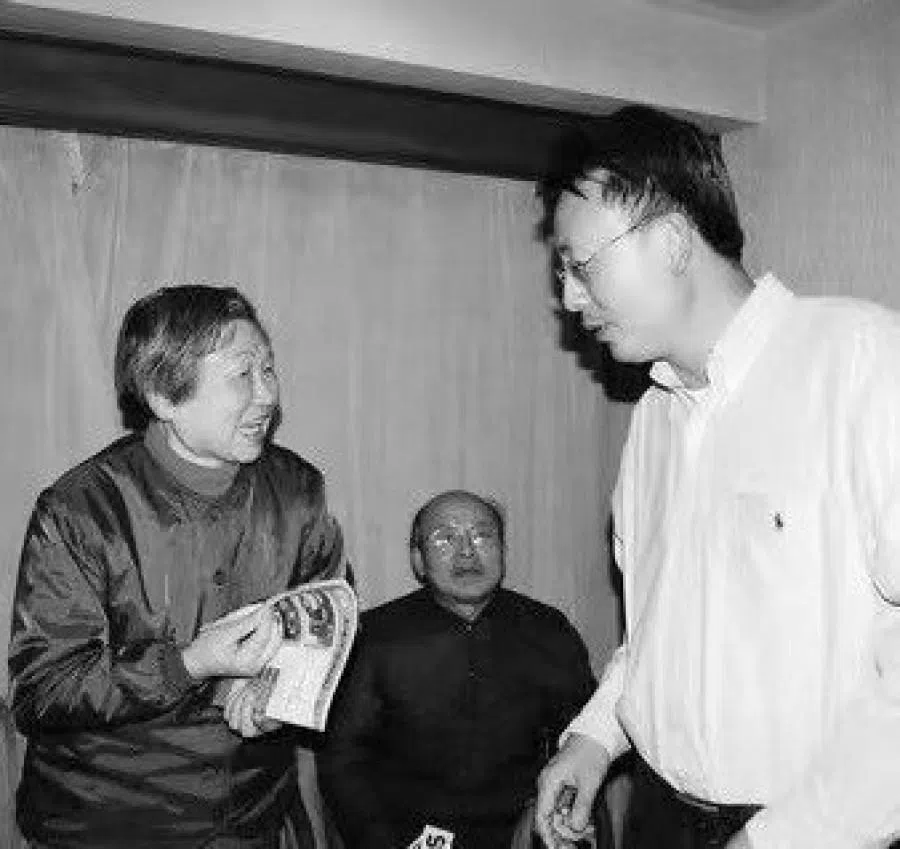

While we were in Shanghai, Zhu Xiaofeng, her husband Mr Xu, and the writer Feng Yitong, made a special trip from Nanjing to see me. Although it was our first meeting, our conversation flowed easily — perhaps because I had long been immersed in historical materials. We talked for quite some time at the hotel, focusing on her mother’s story, especially the period when mother and daughter spent time together before Zhu Feng left for Taiwan, and the letters her mother had written to the family.

Because this was such a painful chapter of her life, Zhu Xiaofeng’s expression was grave. She conveyed her earnest hope that I could help locate her mother’s remains. For Zhu Xiaofeng, her mother had completely vanished with no trace in Taiwan all those years ago. Apart from a few names, everything that occurred after her mother’s execution was a total blank. How her body was handled, where she was buried — there was no information at all.

Drawing on my instincts as an experienced journalist, and having already left the newsroom and thus gained greater freedom in my work (though it came with the burden of making a living, the inevitable price of freedom, which I could handle myself) — I accepted the commission from the 74-year-old Zhu Xiaofeng. From that moment on, I had effectively become a party to the case. I did not know what the outcome would be, but I resolved to give it my all.

The next day, like old friends, we took our children to wander around the science museum, chatting as we walked. At that time, I had no idea that I was about to embark on an important journey of historical investigation.

Uncovering new historical sources

Over the following two years, I devoted myself fully to the investigation, exhausting every possible means. This included publishing reports in newspapers to openly solicit information, as well as privately interviewing individuals involved at the time. In the end, I was still unable to locate Zhu Feng’s remains.

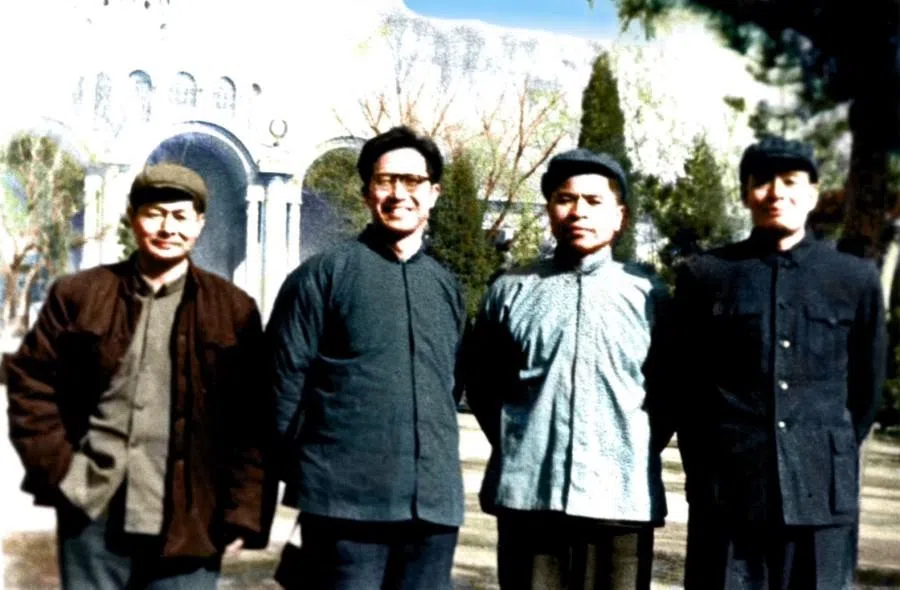

However, I did identify several key figures, and uncovered new historical materials, including information on Chen Lianfang, the stepdaughter with whom Zhu Feng had stayed; Feng Shou’e, who was imprisoned in the same jail as Zhu Feng; Yan Xiufeng, an underground party member whom Zhu Feng had contacted when she came to Taiwan to liaise with Wu Shi; as well as Cai Xiaoqian and Zhang Zhizhong, leaders of the CCP Taiwan Provincial Working Committee at the time; and Wu Ketai (born Zhan Shiping), secretary of the CCP Taipei Municipal Working Committee, who was familiar with senior CCP leaders.

All of the individuals mentioned above have since passed away. I was fortunate to have conducted substantial oral history interviews with them while they were still alive. These accounts not only provided a more emotional understanding of events, but also allowed me, through their narratives, to return more vividly to the circumstances of that time.

“You are from Taiwan — why would you do this?” — A journalist from mainland China asked Hsu

Zhu Feng returns home

In 2010, the family of another CCP agent who had perished passed along new information from the mainland, having discovered an important clue. Five years after I had almost ceased my investigation — and after Zhu Xiaofeng herself had given up hope — a new spark of possibility was reignited. I entrusted Professor Chu Hong-yuan of Academia Sinica with the task of carrying out the on-site search. He was extremely meticulous, entering an ash-storage building that had been left unused for over fifty years and was thick with dust. Among more than three hundred bags of ashes, he located Zhu Feng’s funerary urn. Truly, perseverance is rewarded.

When the news reached Zhu Xiaofeng’s family in Nanjing, they were overjoyed. The task of transporting the remains was then taken over by Zhu Xiaofeng’s son-in-law, Li Yang. Highly capable, he travelled back and forth across the Taiwan Strait, resolving a series of extremely thorny technical issues. Finally, in December 2011, Zhu Feng’s remains were brought back to the mainland. They were first temporarily placed at the Babaoshan Revolutionary Cemetery in Beijing, and later, under arrangements by the Ministry of State Security, transported by special aircraft back to her native place in Zhejiang for burial.

This event naturally caused a major stir on the mainland, with extensive coverage across television and newspapers. It ultimately led to the erection of the Martyrs’ Memorial and four statues at Beijing’s Western Hills in 2013.

Prioritising cross-strait reconciliation over historical grievances

CCTV journalist Chai Jing sought me out and conducted an exclusive interview with me at the café on the first floor of the Overseas Chinese Hotel where I was staying. In fact, the most crucial question she asked was: “You are from Taiwan — why would you do this?” By this she meant: why would I devote myself fully to helping locate the remains of CCP martyrs and assist in returning them to their hometowns for burial?

My answer was very clear. “In Taiwan, I am also asked: if KMT agents had fallen into the hands of the Communist Party, would the Communists have treated them kindly? And if Zhu Feng and her comrades had succeeded, would Taiwan — after experiencing campaigns of political purges and the calamities of the Cultural Revolution — have gone on to achieve its later economic success?”

My response was: “I cannot say that this line of reasoning is wrong. But the long river of history is full of twists and turns, and it is very difficult to extract a single segment and use it to make an all-encompassing judgement. What matters is that while we live with the past, we live even more in the present and the future. If we remain trapped in the mutual vendettas and killings between the KMT and the CCP, we will never achieve genuine peace, nor will we be able to create a shared future. We should decide that past grievances end here, stop the endless cycle of revenge, while still respecting each other’s roles in their respective struggles. From this point forward, we should move toward reconciliation and cooperation — only then can we have a bright future. These are not empty words, but a matter of opening our hearts, bidding farewell to one chapter of history, and beginning another.”

I knew that this portion of my remarks would never be aired in a CCTV interview, but I still felt compelled to say them. I said the same things to Zhu Xiaofeng, Feng Yitong, Li Yang and others. In fact, while we were engaged in this work, cross-strait relations reached a new high point: business and tourism exchanges flourished, and eventually the Ma-Xi meeting was realised. I am not claiming that our efforts had any major political impact, but they did lay an important spiritual foundation for reconciliation across the Taiwan Strait and between the KMT and the CCP.

From suppression to commemoration

There is also another important issue. In the past, matters concerning CCP agents in Taiwan were suppressed by the mainland authorities. Why, then, are they now being made public — indeed, even vigorously promoted? The reasons are quite simple. First, the activities of CCP agents in Taiwan were essentially still considered “party secrets”, and therefore could not be casually disclosed. Second, while many agents sacrificed their lives, there were also not a few who betrayed the party. In the end, their operations were failures, which was difficult to align with the narrative of a “glorious victory”.

... they are portrayed as heroic sons and daughters, and in such narratives, there can be no major flaws in their character. What I encountered through my interviews, however, were flesh-and-blood individuals with complex lived realities.

Finally, many underground party members who were killed were later officially labelled as traitors. After the Cultural Revolution ended, some were rehabilitated, but many more, due to bureaucratic obstacles, still have documents branding them as traitors locked away in the archives of specific agencies. For their families today, this remains a profound source of pain, and they have collectively demanded redress.

Thus, whether viewed from the broader historical context, the reconciliation between the KMT and the CCP, or the political need for rehabilitation, all these factors have pushed mainland authorities to open up reporting on this chapter of history, and to further promote the stories of fallen agents as narratives of honorable sacrifice. This is the situation we see today.

The human realities beneath heroic narratives

Of course, at a time when pro-independence forces hold power in Taiwan and are pushing a separatist agenda, the promotion of the sacrifices of CCP agents does not necessarily signify a history of reconciliation; it may instead symbolise a completely different political signal.

At the same time, on another level, publicity reports and dramatic productions inevitably mythologise and dramatise the characters. After all, they are portrayed as heroic sons and daughters, and in such narratives, there can be no major flaws in their character. What I encountered through my interviews, however, were flesh-and-blood individuals with complex lived realities.

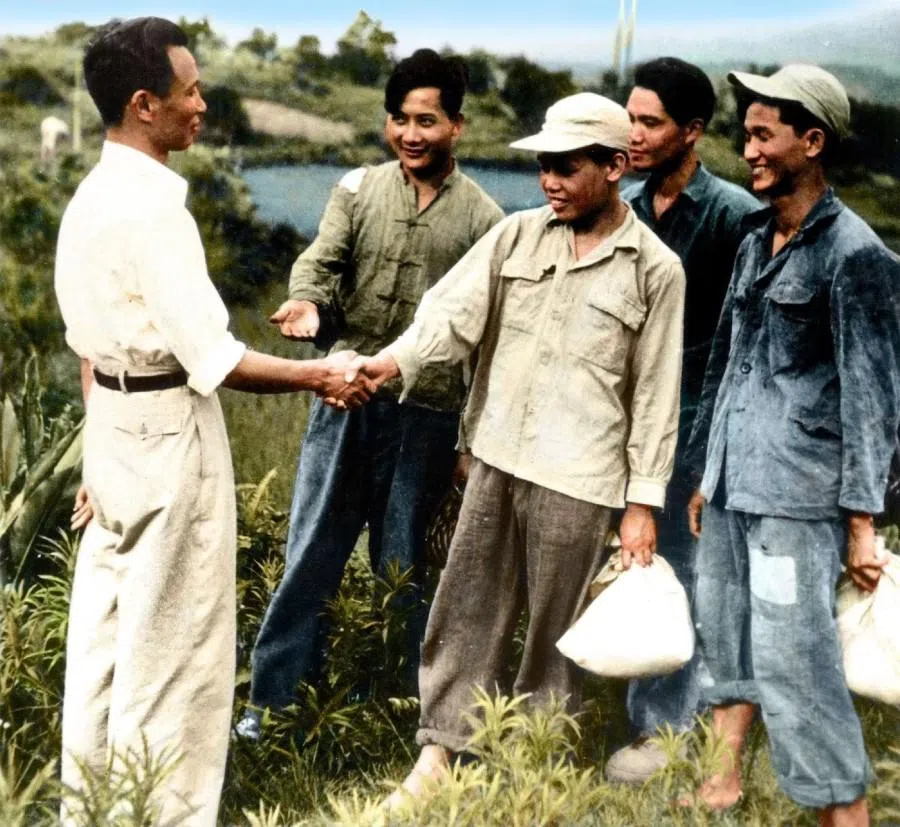

Take, for example, General Li Youbang, who founded the Taiwan Volunteer Corps in Jinhua, Zhejiang. He received strong support at the time from Zhou Enlai, then deputy director of the Military Commission’s Political Department, which meant that from the very beginning the Taiwan Volunteer Corps bore a clear Communist imprint. Li Youbang’s wife, Yan Xiufeng, was a native of Hangzhou, Zhejiang. She had joined the CCP early on and was an old acquaintance of Zhu Feng. Zhu Xiaofeng herself had spent part of her childhood in the Taiwan Youth League. Therefore, when Zhu Feng came to Taiwan to carry out her mission, she also met with Yan Xiufeng.

Yan Xiufeng was later arrested and spent fifteen years in prison. However, she was not exposed by Zhu Feng. Rather, it was Ji Yun, the wife of Zhang Zhizhong — then deputy secretary of the CCP Taiwan Provincial Working Committee — who informed on her. This is mentioned in the case file of Zhang Zhizhong’s arrest. Yan Xiufeng said to me in a grave tone, “I will never forgive Ji Yun.”

Later, when I told Wu Ketai — who had served as secretary of the CCP Taipei Municipal Working Committee — about Yan Xiufeng’s words, Wu smiled and said, “I know. But Ji Yun herself was later executed, so there’s really nothing more to say.” Wu Ketai then added, “All of us at the level of secretary and above were executed.” He said this with remarkable composure, which gave me a sense that the generation of Chinese revolutionaries who had walked that path lived in an environment where life and death seemed scarcely worth mentioning, which is almost unimaginable to us today.

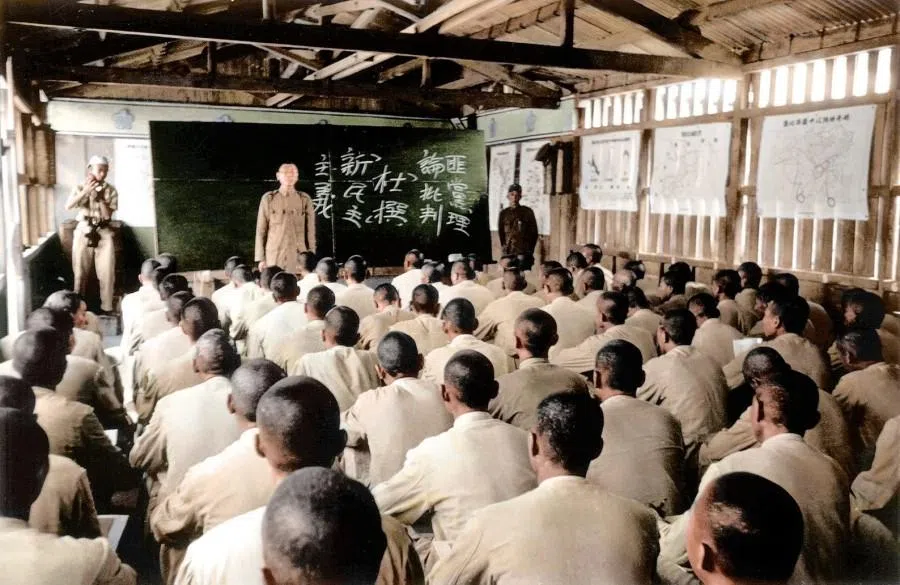

The coexistence of revolutionary idealism and brutality

By 1949, the overall outcome of the Chinese Civil War had been decided. The People’s Republic of China was founded, and the complete victory of the Communist forces in crossing the sea seemed only a matter of time. The CCP Taiwan Provincial Working Committee accelerated its recruitment of party members and began preparing to organise efforts to welcome the PLA’s arrival in Taiwan. As a result, the composition of new members became more complicated, and vetting standards were relaxed. Some underground party members even went so far as to flaunt and hint at their identities, suggesting that they would soon become officials taking over authority and smugly inflating their own importance.

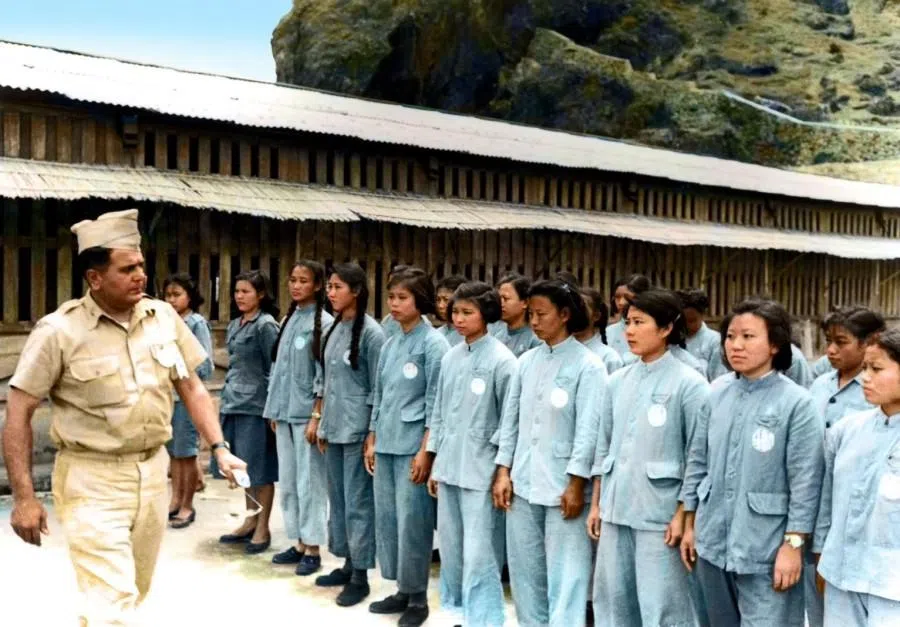

This situation quickly led to the collapse of the underground party network. Members lacked steadfastness and, under pressure, revealed everyone at once. Yan Xiufeng complained bluntly, “At that time, recruitment into the party was not about quality at all. Any Tom, Dick, or Harry could join.”

In addition, the KMT, facing existential peril, resorted to ruthless measures. Even some CCP underground members who had already defected were not spared; they were executed all the same. Based on experience from the mainland, the KMT believed that once such people were released, a change in circumstances could cause them to switch sides again, returning to the CCP camp and attacking the KMT with even greater intensity. This time, they decided to abandon any pretense of leniency and carried out mass executions.

This reveals the duality of revolutionary violence, where the purest ideals and the greatest cruelty coexist as one.

In fact, I have seen claims on mainland platforms that Cai Xiaoqian was subjected to brutal torture and only then forced to betray all his comrades. This is not true. Cai Xiaoqian surrendered very quickly. The Taiwan-born CCP cadre, who had participated in the Long March, had in fact long-harboured deep dissatisfaction with the party. In his own published statement, he said: “For the past 20 years in the Chinese Communist Party, I lived in fear every single day.”

This reveals the duality of revolutionary violence, where the purest ideals and the greatest cruelty coexist as one. I actually believe that what he said was heartfelt.

All of these were the historical realities I came to understand through direct encounters with those involved. They are not records that can be preserved through written documents alone today, yet they vividly restore history to life.

Unlike the sorrowful expression she had worn more than a decade earlier when she entrusted me with this task in Shanghai, this time she was radiant and full of contentment. I knew that her mother’s soul had returned to her native land, and that the greatest wish of her life had finally been fulfilled.

A spiritual denouement

In the end, this work had several profound psychological effects on me. A few years ago, I once mentioned this matter to Venerable Miaoxi, a senior female disciple of prominent Buddhist monk Master Hsing Yun. I told her that I had helped the family of an important CCP agent locate the mother’s remains in Taiwan and return them to her hometown for burial. Venerable Miaoxi said, “This is a great karmic blessing.”

Later, on another occasion, I visited Zhu Xiaofeng at her home in Nanjing. She received me warmly. Unlike the sorrowful expression she had worn more than a decade earlier when she entrusted me with this task in Shanghai, this time she was radiant and full of contentment. I knew that her mother’s soul had returned to her native land, and that the greatest wish of her life had finally been fulfilled.

Several years after that, I received a text message from Li Yang, telling me that his mother-in-law, Zhu Xiaofeng, had passed away. This episode from long ago had now settled like dust in the Zhu family’s history, reaching a complete and peaceful conclusion.

There was, however, a sequel to this story for me. Zhu Xiaofeng’s daughter — Zhu Feng’s granddaughter — Xu Yunchu, together with her husband Li Yang, invited me to dinner in Beijing. Perhaps it was a matter of generational inheritance, but Xu Yunchu bore a striking resemblance to Zhu Feng. As she sat beside me, smiling and speaking, I felt for a moment as if it were Zhu Feng herself talking to me. It was an encounter that seemed to transcend lifetimes, as though bound by a destiny carried across generations.

I am not a superstitious person. I do not go to temples to seek divine guidance, nor do I practice fortune-telling or divination; I have never believed in such things. Yet over the past few years, whenever I encountered major challenges — especially those that posed a threat to my inner world — I repeatedly sensed, in some intangible way, that Zhu Feng’s spirit was watching over me, giving me a kind of spiritual strength that helped me withstand various blows.

I know that most people would say I am talking nonsense, or that I have lost my mind. Perhaps so. Even so, from the moment I committed myself to this work, I have always listened to the voice within my heart. That unseen force, whatever it may be, can only remain there quietly, forever.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)