Old Singapore: Of wells and life

Hua Language Centre director Chew Wee Kai reminisces about the wells that he used to know as a child, and the stories and memories evoked of Singapore in the 1960s, in the days of water rationing and floods, when water did not come from turning on a tap, but tapping into the ground.

One evening about two years ago, I went alone to a small food court outside the Botanic Gardens for some me-time. With my tea in hand and my mask off my face, the air smelled free. It wasn't long before someone approached and said hello - it was the sculptor Sun Yu-li, whom I hadn't met in ages. After chatting for a moment, I asked about his zinc-roofed holiday home on Pulau Ubin. "Sold it long ago," came the placid reply.

I miss the well in front of that house, near Chek Jawa. Over 20 years ago, some friends and I went there. When we arrived, it was nearly night. To our surprise, we found the well - we looked in and saw that there was plenty of water, so we hauled up a pail. The water was clear and cool, and we happily dropped our things in our haste to enjoy getting splashed.

Everyone stood beside the well and took turns pouring the water over our heads; our voices quickly rose in pitch as the icy coldness of the water hit us, and the utter joy of the moment brought us back to our youth. I had left village life over ten years earlier, and it was a rare thing to relive the raw pleasure of drawing water and bathing in it.

When the well of village fun never runs dry

There were no streams in my village, and in over 20 years of rural life, wells were a constant feature. In the days before villages had tap water, nearly every household had a well and a waist-high earthen jar - when it was empty, you could put your head in the jar and have fun with your own echoes; when it was full, it held clean potable water hauled back from the public taps. Water for other daily use such as ablutions, household animals and planting were up to the good graces of those wells. But if there was a drought and the wells dried up (which was rare), there was nothing to be done.

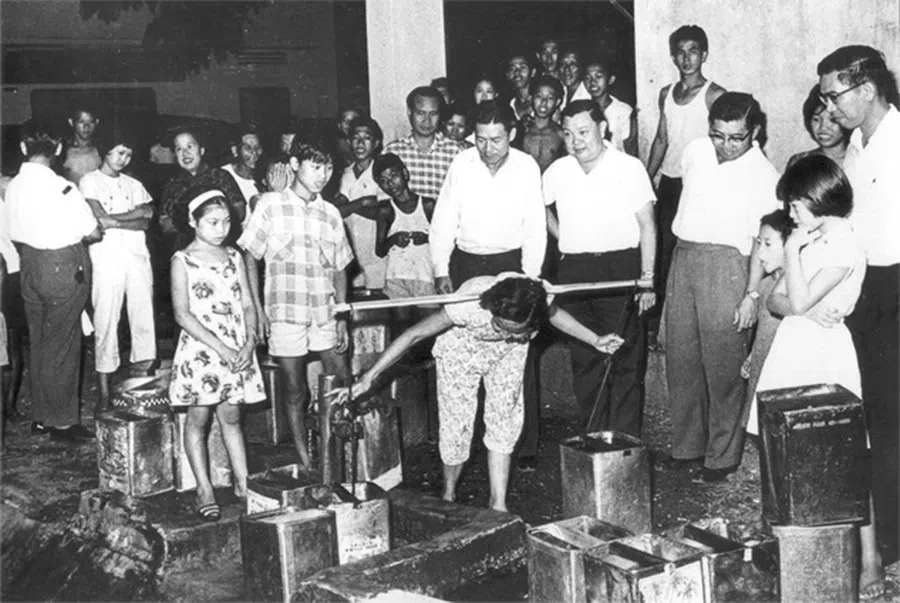

Whenever there was water rationing, there would be a queue of sleepy-eyed people at the public taps from about 4am, quietly waiting for the water to come on. During those times, large households could take turns queuing, while others could only turn up alone. In the major water rationing exercise of 1963 amid a long ten months of drought, people truly felt that water is life.

I found that my school bag, which I had thrown on the floor, was all wet. I hurriedly opened it - and a fish jumped out.

The well at my old home was located right beside the kitchen, following some late-night survey efforts by my dad and our neighbour Uncle Jiang to locate its source. I don't know how the adults found water sources; in any case, once they found a spot, each dig brought its surprises.

Dad went all out, stacking red bricks from the bottom of the well all the way up, while the well opening was wider than most, which was in character for Dad. That well was the most intricate structure in our household, rimmed by a three-foot concrete area and a little drain running around it for good drainage. The day after the well was finished, my father put in some pieces of alum - aluminium sulphate - and the water became clearer.

One day, it poured and the house was badly flooded. I found that my school bag, which I had thrown on the floor, was all wet. I hurriedly opened it - and a fish jumped out. I held it and sprinted to drop it in the well, and after that, the well had something new in it.

The following year, there was a drought and the skies and clouds were no longer reflected as the water quickly ran dry and our worries ran deeper. Each day, I couldn't help but put my head in and check the bottom of the well, but there was no sign of the fish.

Digging deep, building foundations

Years later, tap water was laid on in the village and the shoulder poles and pails were retired; but that earthen jar stayed in the bathroom. I loved the coolness of the well water - whenever I had time, I would get some and fill the jar, and enjoy the natural chill of the water in the summer heat, right up until we moved away.

I asked him why he didn't quit drinking since he drank all his money away. His only response was a silly grin.

There were actually two wells at my old home. The other well was an ugly looking one, dug later by an elder I called "Grandpa" as a term of respect. He was mild-natured, hard of hearing and a hard drinker. He was about ten years older than my father, doing odd jobs and living hand to mouth. During festive occasions, my father would invite him to our home for a drink; I got the feeling that getting him to dig the second well was my father's way of helping out a fellow villager.

This well was much smaller, just next to the pig sty. I was in lower secondary school when it was dug. The work began during the summer holidays - I worked with Grandpa Wu, with him digging as I shifted the soil. The work was not tough, because there was no set date to finish.

During one of our breaks, Grandpa Wu used himself as a negative example. He reiterated two motifs: one, study well and not be an illiterate ne'er-do-well like him; and two, don't drink because alcohol turns people bad. I asked him why he didn't quit drinking since he drank all his money away. His only response was a silly grin.

Lost but not forgotten

The well was completed a little sloppily. It was much shallower than expected, and there were two concrete well rings left over. Years later, Grandpa Wu expressed a wish to go back to his hometown. My father organised his trip and prepared two large wooden cases of items for his triumphant return. A single man away from home for sixty years - he was fortunate to return to where he came from. Before he left, we bumped into each other at the village coffeeshop, and he repeated his admonishment at the well: study hard and don't drink.

Many memoirs begin at a well; many daily vignettes revolve around the well beside the house.

The Chinese say lixiang beijing (lit. leaving home with back to the well, 离乡背井). Leaving home is a cultural phenomenon that has been around for millennia. The May Fourth Movement poet Liu Yanling, who lived in Singapore for sixty years, also wrote wistfully of the well: "He recalled the well where the pomegranate flowers bloomed so brightly. Beside it, she was hanging out her green top on the bamboo frame." This slice of life beside the well defines the memory of home for someone far away.

Many memoirs begin at a well; many daily vignettes revolve around the well beside the house. Amid rapid social change, the once-full circle of the well has long since shrunk to an insignificant little full stop at the end of a sentence.

Related: The stories behind the woodcuts | [Photo story] When tropical Singapore was 'too potent to be conquered' | [Photo story] Taiwanese historical photo collector: My ties to Singapore | What old Chinese textbooks say about life and times in Singapore | Memories of South China: The enchanting garden that Whampoa built in Singapore

![[Big read] Love is hard to find for millions of rural Chinese men](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/16fb62fbcf055b710e38d7679f82264ad682ce8b45542008afeb14d369a94399)

![[Big read] China’s 10 trillion RMB debt clean-up falls short](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/d08cfc72b13782693c25f2fcbf886fa7673723efca260881e7086211b082e66c)