After Vietnam, after Trump: Can the US still anchor Asia?

From Cold War shifts to Trump’s unpredictability, Asia’s balance hinges on a stronger China, wary allies and an uncertain US role. Can America still anchor regional security?

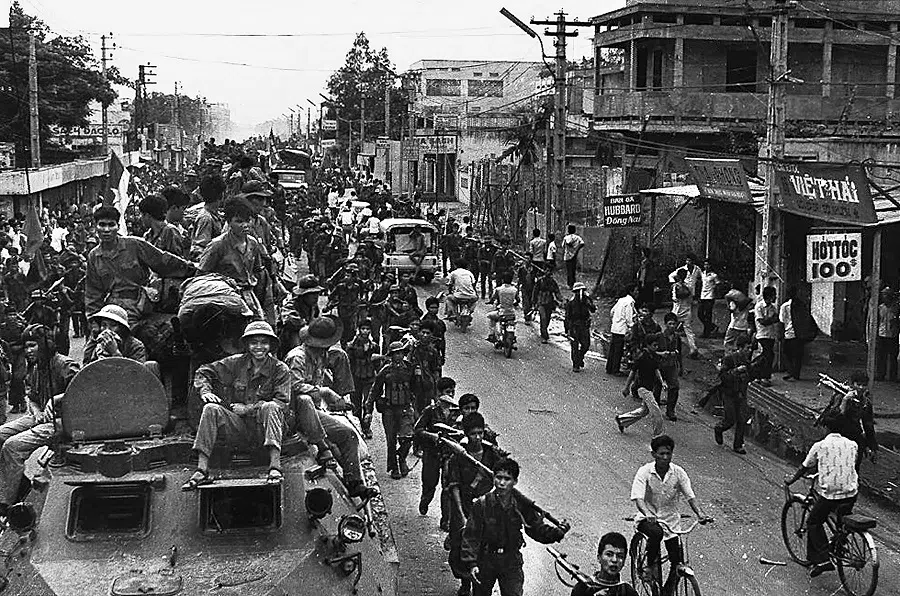

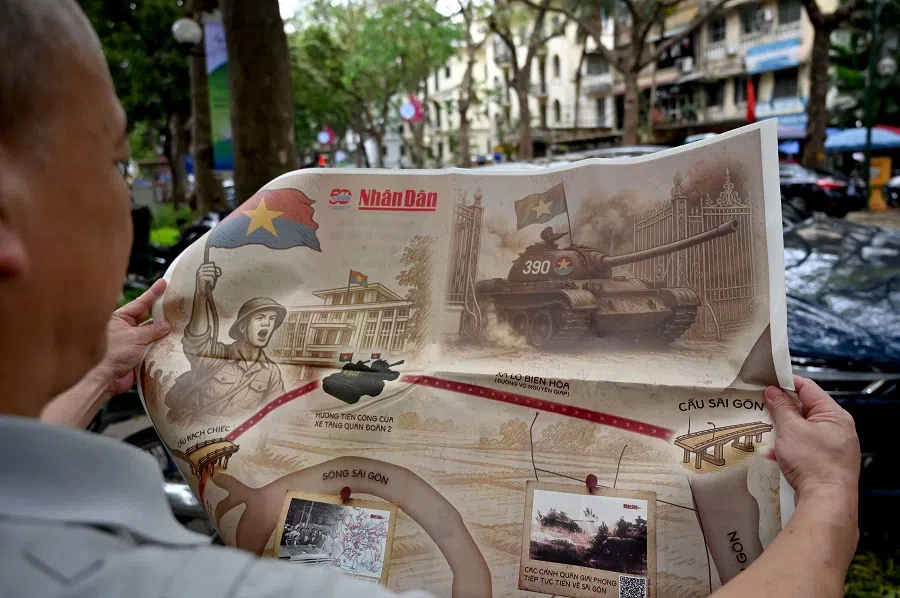

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the end of “America’s war” in Vietnam from 1965 to 1975. The US entered the war in the closing years of an era when it was prepared to fight communist expansion wherever it occurred. This policy was initially signalled by the Truman Doctrine.

The Vietnam War was a catastrophe in terms of its huge human toll and economic cost, and many Americans viewed it as a tragic folly. However, it proved to be a protective shield against the spread of communism in Southeast Asia. Without direct US military intervention in Vietnam in 1965, the Southeast Asia that we know today may not have existed.

Despite the US’s setbacks in Vietnam, it has remained a vital component of the Asia- Pacific power balance. However, now the policies of the Trump administration — to reshape the global trade order and US security posture — have generated uncertainties about the adjustments to come, including the roles of its allies and partners.

The threat of communism and uncertainties about the outcome of the Vietnam war were among the factors that led to ASEAN’s formation in 1967.

Importance of the US

The domino theory, fashionable in US policy circles in the 1950s and early 1960s in its extreme form, assumed that if Vietnam fell to the communists, the rest of Southeast Asia would follow suit. In the US, the theory had its leftist and progressive critics and establishment figures, who thought it was too simplistic. Non-communist Southeast Asian governments were also deeply concerned about the potential spread of communism from Vietnam.

The American military intervention in March 1965 removed the danger of an imminent communist victory in South Vietnam. It also strengthened the confidence of the army generals in Indonesia who, after an abortive pro-communist coup of September 1965, set up an anti-communist government in Jakarta and moved to destroy the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI). The threat of communism and uncertainties about the outcome of the Vietnam war were among the factors that led to ASEAN’s formation in 1967.

In 1975, when South Vietnam fell to the communists, there was again alarm that the domino theory might materialise because, after the US’s withdrawal, there was no countervailing power to balance China and Vietnam’s million-strong battle-hardened army. Laos and Cambodia fell quickly, but other countries did not, because the US’s involvement in the war bought time for changes to take place in the region’s international relations, to non-communist Southeast Asia’s benefit.

Without the US, no combination of Asian countries could balance China.

Sino-Soviet relations had deteriorated sharply, while failures in Vietnam influenced then US President Nixon’s opening to China, leading to US-China detente. Within a few years, Sino-Soviet rivalry spread to Southeast Asia, with Vietnam as a Soviet partner. To thwart the perceived Soviet threat to its interests in the region, China started cultivating Southeast Asian governments and abandoning support for communist insurgencies. Thus, remarkably, China became a balancer against Soviet-Vietnam ambitions in the region, in political partnership with the US.

Despite some initial scepticism after its ignominious withdrawal from Vietnam, the US remained an indispensable player in the Asia-Pacific security arena, maintaining its key alliances and deterrent power, except for its withdrawal from the Philippines bases in 1991-92, at Manila’s request. Most non-communist countries in this region came to recognise the US’s importance, as regional dynamics changed after the collapse of the Soviet Union and China ceased to be strategically aligned with the US. Without the US, no combination of Asian countries could balance China.

How committed is the US?

The Vietnam experience produced the Nixon Doctrine, according to which the US would not again fight a land war with ground troops in the Asia-Pacific. It would instead pursue a largely maritime strategy based on naval and air power — reflecting a more judicious use of power and avoiding involvement in foreign wars which did not serve vital US interests.

This came to be dubbed as “conservative realism”, which has remained the basic template for the US’s policy vis-à-vis the Asia-Pacific. While the US has been committed to South Korea’s defence, for instance, much of the burden of fighting a land war will be South Korea’s responsibility.

Anxiety among the US’s Asian allies and friends about the durability of its security presence is not new. There has always been an undercurrent of it because the US is a distant power and has had a long history of isolationism.

In recent years, the challenge from a China that is now far more powerful has led to the rise of quadrilateral and trilateral arrangements to strengthen extended deterrence.

Anxiety among the US’s Asian allies and friends about the durability of its security presence is not new. There has always been an undercurrent of it because the US is a distant power and has had a long history of isolationism. The anxiety becomes more acute at certain times, such as after the US’s withdrawal from Vietnam and after the Cold War, when unease surfaced about whether the US would continue to deploy significant forces in the Western Pacific.

Rising China and unpredictable Trump

Changes in the strategic balance in the Western Pacific, including the China-Russia and the North Korea-Russia alignments, and in domestic US politics, have been propelling new adjustments to the US’s strategic posture in this region. The growth of China’s military power is making it even more challenging for Washington to maintain deterrence without much stronger allied support. Hence, the US is increasing pressure on Asian allies to spend much more on defence.

A landmark policy statement akin to the Truman or Nixon Doctrine is needed. Can there be a credible Trump Doctrine, given the internal contradictions in his Administration and Trump’s inconsistencies and unpredictability?

Though the US might not withdraw substantially from the Asia-Pacific, uncertainties have arisen about what adjustments are required from its allies and partners. This uncertainty is compounded by Trump’s tariff war.

Trump has a world view and a vision of what America’s role in the world should be, which is often obscured by his capriciousness and grandstanding. A landmark policy statement akin to the Truman or Nixon Doctrine is needed. Can there be a credible Trump Doctrine, given the internal contradictions in his Administration and Trump’s inconsistencies and unpredictability?

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.