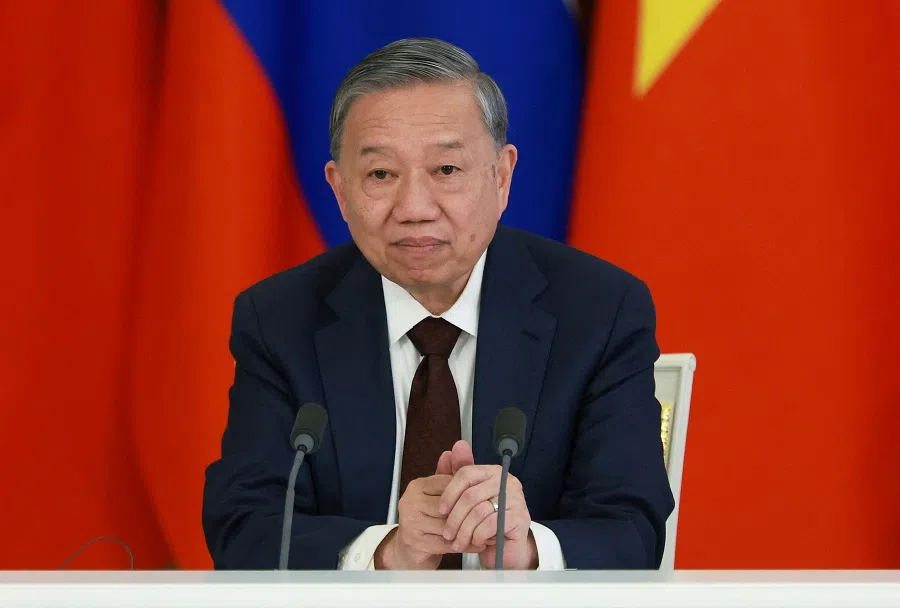

To Lam’s rise and Vietnam’s move into the former Soviet sphere

Vietnamese leader To Lam’s recent tour of Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan was aimed at diversifying Hanoi’s strategic partnerships and securing Moscow’s backing for its military needs and South China Sea claims.

In May, To Lam, general secretary of the Communist Party of Vietnam (CPV), concluded an extensive eight-day tour across Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Russia and Belarus — his longest overseas trip since taking office last August. Notably, this was the first visit by a CPV chief to Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan since the Cold War, and marked the first participation by a top Vietnamese leader in Russia’s Victory Day celebrations.

At first glance, the timing seemed peculiar. At home, the National Assembly was in session, deliberating To Lam’s ambitious domestic reform agenda. Abroad, the image of Vietnam’s leader sharing the same stage with Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and Chinese President Xi Jinping on Moscow’s Red Square inevitably raised eyebrows in the West. Economic ties with the four countries he visited remain modest — combined bilateral trade in 2024 amounted to less than US$6 billion, roughly 1% of Vietnam’s total trade — hardly justifying such diplomatic risks. What, then, explains this diplomatic detour into the former Soviet sphere?

The answer lies in Vietnam’s sophisticated hedging strategy. As great powers redraw the global geopolitical landscape, Hanoi seeks to fortify its strategic position through diversification with as many partners as possible.

Balancing China: Vietnam’s Russian strategy

Central to To Lam’s tour was his Moscow visit. As Russia and China deepen their “no-limits” partnership, Hanoi needs assurances from Moscow that it will not side with Beijing in the South China Sea disputes. The joint statement released at the end of To Lam’s visit deftly addressed this concern, reaffirming Vietnam’s long-standing position on upholding the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and the Declaration on Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea, while signalling strengthened defence cooperation and expanded Russian energy operations on Vietnam’s continental shelf. For Hanoi, these are crucial guarantees: its maritime claims depend heavily on Russian arms supplies and energy cooperation.

Vietnam’s military remains overwhelmingly reliant on Russian hardware, accounting for about 80% of its arsenal, and Russian logistics and training.

Despite Western sanctions stemming from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Vietnam’s military remains overwhelmingly reliant on Russian hardware, accounting for about 80% of its arsenal, and Russian logistics and training. Although Hanoi has begun exploring arms deals with other partners such as South Korea, Israel and Europe, an abrupt pivot away from Russia would severely undermine Vietnam’s military capabilities precisely as China’s assertiveness intensifies.

Energy cooperation is equally critical. Over the past decade, while Western energy giants like Repsol withdrew from projects in Vietnam’s continental shelf under Chinese pressure, Russian state-owned firms such as Zarubezhneft have stayed put, supporting Vietnam’s energy security and implicitly backing its territorial claims.

Perhaps most telling was Rosatom’s agreement to develop nuclear technologies in Vietnam through 2030 — effectively reviving nuclear energy ambitions shelved in 2016 due to cost concerns. With electricity demand projected to surge at least 10% annually amid Vietnam’s economic boom and a pledged net-zero target by 2050, the collaboration with Russia, previously responsible for training most Vietnamese nuclear engineers, offers a pragmatic pathway for an increasingly energy-hungry nation.

Its leadership clearly recognises the risks of dependence on any single global power, particularly since US President Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs, which threaten Vietnam’s export-driven economy.

Diversification and multiple partnerships

Equally strategic were To Lam’s unprecedented visits to resource-rich Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan. High on the agenda were discussions to enhance oil and gas cooperation — crucial for Vietnam’s energy security. Kazakhstan, the world’s largest uranium producer, could support Vietnam’s renewed interest in nuclear energy, whether by supplying uranium directly or aiding in developing capacity to extract its domestic reserves.

Geo-economically, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan are pivotal nodes along the trans-Caspian corridor, potentially providing Vietnam an alternative route to its major European markets once Vietnam’s railway connection with China is completed in the near future.

Such diversification demonstrates Vietnam’s strategic foresight. By cultivating multiple partnerships, Hanoi seeks to maximise autonomy and reduce geopolitical vulnerability. Its leadership clearly recognises the risks of dependence on any single global power, particularly since US President Donald Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs, which threaten Vietnam’s export-driven economy.

The need for diversification explains why strengthening trade ties featured prominently throughout To Lam’s tour, resulting in over 60 cooperation agreements. Vietnam already enjoys free trade arrangements with three of the four countries visited — Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus — through the Vietnam-Eurasian Economic Union Free Trade Agreement, which will provide a ready-made framework for expanding economic cooperation.

To Lam: architect of Vietnam’s foreign policy

Diplomatic neutrality remains integral to Vietnam’s diversification strategy. In his meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, To Lam carefully reaffirmed Vietnam’s commitment to international law and peaceful conflict resolution when calling for an end to the war in Ukraine. Notably, he is among the few world leaders who have met both Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy in person since Russia’s 2022 invasion.

Since assuming leadership, To Lam has conducted 13 state visits compared to President Luong Cuong’s three, adding to speculation that Vietnam’s traditionally ceremonial presidency might be merged with party leadership at next year’s congress.

However, this balancing act is not without risks. Western governments have signalled increasingly stricter enforcement of sanctions against Russia and its alleged supporters. On 14 May, the European Union’s latest sanctions targeting Russia’s “shadow” oil fleet ensnared some Vietnamese companies, illustrating how deeper ties with Moscow could jeopardise Vietnam’s critical economic relationships with the West. Nevertheless, Hanoi obviously calculates that strategic autonomy is worth the gamble, benefiting both national interests and To Lam’s domestic agenda.

This tour, upgrading ties with Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan and Belarus to strategic partnerships, further consolidates his role as Vietnam’s de facto head of state. Since assuming leadership, To Lam has conducted 13 state visits compared to President Luong Cuong’s three, adding to speculation that Vietnam’s traditionally ceremonial presidency might be merged with party leadership at next year’s congress. If this happens, To Lam will be the clear favourite to take the unified position.

Ultimately, To Lam’s Eurasian diplomacy underscores Vietnam’s persistent drive towards a multi-directional foreign policy amid increasing pressure from rival superpowers to pick sides. Hanoi’s diplomatic playbook suggests true strategic autonomy comes from diversified relationships, which create both leverage and resilience. In today’s fractured geopolitical landscape, this might well be the wisest strategy for middle powers caught in the crossfire of great power competition.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.