America’s energy pivot and the ripple effects on East Asia and the Middle East

The US’s reversal of its climate change policies and shift towards increasing energy production and exports is making some countries and regions nervous. Academic Hao Nan looks at the impact of Trump’s decisions, especially for East Asian economies and the Middle East region.

Suggesting a potential restructuring of its energy imports, Taiwan’s economy ministry announced on 10 February that it is assessing the feasibility of purchasing natural gas from Alaska. This follows Japan’s recent commitment at the Trump-Ishiba summit on 7 February, where the two leaders pledged to enhance energy security by increasing US liquefied natural gas (LNG) exports to Japan. South Korea, too, has signalled interest in diversifying its energy sources with more oil and gas purchases from the US, with Industry Minister Ahn Duk-geun in January emphasising the need for stable supplies amid escalating tensions in the Middle East. This shift aligns with Trump’s ambitions to position the US as a dominant fossil fuel exporter, but it could also exacerbate instability in the Middle East.

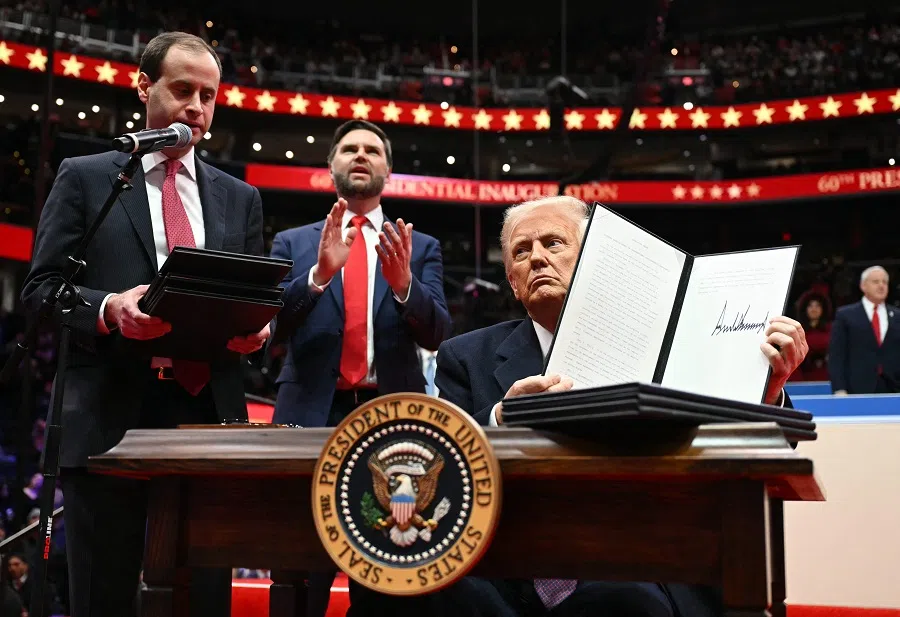

After President Trump’s inauguration, the US is once again prioritising fossil fuel expansion as a cornerstone of its economic and geopolitical strategy. The administration has wasted no time in reversing climate policies, rolling back emissions regulations and lifting restrictions on oil and gas exports. In fact, under Trump’s first presidency, the US has been a net total energy exporter since 2019. More recently, in 2024, the US retained its position as the world’s largest LNG exporter, with its LNG exports hitting 88.3 MT, up from 84.5 MT in 2023. In 2023, US crude oil imports and exports both increased in 2023, and the US remained a net crude oil importer. Trump’s administrative push, removal of restrictions and tariffs on foreign energy products, are anticipated to increase the US’s energy production and exports, though whether the effect would be immediate is subject to the energy market’s situation.

Apart from China and Vietnam’s US$279 billion and US$105 billion trade surplus, South Korea and Japan both have over US$50 billion trade surplus with the US.

East Asian players reassessing dependence on Middle East energy

This shift is already having profound implications for East Asia, where regional actors like Japan, South Korea and Taiwan are reassessing their reliance on Middle Eastern energy supplies. At the same time, the move threatens to destabilise Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) economies, potentially reshaping alliances and security commitments in the Middle East.

For decades, East Asian economies have been overwhelmingly dependent on the Middle East for their energy needs. In 2023, GCC nations supplied a staggering 95% of Japan’s crude oil imports in 2023, 72% of South Korea’s, and 69% of Taiwan’s. The numbers for natural gas tell a similar story, with Qatar alone providing 28% of Taiwan’s supply and 21% of South Korea’s. The US, by contrast, played a relatively minor role, accounting for only 2% of Japan’s oil imports, 14% of South Korea’s and 27% of Taiwan’s, and 12% of South Korea’s gas imports and 10% of Taiwan’s.

Beyond energy security, economic considerations are also driving this realignment. East Asian countries have long run significant trade surpluses with the US. In 2023, almost all East Asian countries, except Singapore, maintained a trade imbalance in their favour. Apart from China and Vietnam’s US$279 billion and US$105 billion trade surplus, South Korea and Japan both have over US$50 billion trade surplus with the US. These imbalances have been a persistent source of tension, and Trump has repeatedly criticised trade deficits as evidence of unfair economic practices.

While Riyadh benefits from its strategic relationship with Washington — receiving military protection and maintaining economic ties — it also understands that an increasingly self-sufficient US could reduce its commitment to Middle East stability.

Energy trade presents a potential solution. By increasing their imports of US fossil fuels, East Asian economies could narrow their trade surpluses and reduce political friction with Washington. However, this shift comes at a cost — specifically, the economic security of the Middle East, which has long depended on stable demand from Asia to sustain its fossil fuel-reliant economic diversification efforts.

GCC countries may need to find alternative markets

As East Asia pivots toward US energy supplies, GCC nations face a dilemma. If their primary customers begin sourcing fuel elsewhere, they will be forced to find alternative markets or risk slower pace and lower market confidence in funding their ambitious economic diversification projects. This vulnerability is particularly pronounced for Saudi Arabia, which has been hesitant to fully embrace BRICS, the economic bloc seen as a counterweight to Western financial dominance, since the country was invited in 2023. While Riyadh benefits from its strategic relationship with Washington — receiving military protection and maintaining economic ties — it also understands that an increasingly self-sufficient US could reduce its commitment to Middle East stability.

This could explain recent US actions in the region. The Trump administration’s decision to expedite US$8.4 billion in weapons sales to Israel — bypassing congressional oversight — suggests a prioritisation of strategic influence over diplomatic caution. Additionally, Trump’s proposal to “take over” Gaza and transform it into a “Riviera of the Middle East” and his threat to cancel the ceasefire deal raise questions about Washington’s long-term intentions. If the US is moving toward energy self-sufficiency and competing directly with Middle Eastern oil producers, its commitment to stabilising the region could wane.

Saudi Arabia’s reluctance to fully commit to BRICS membership stems in part from its longstanding economic relationship with the US, particularly through the petrodollar system, which has historically linked oil sales to the American currency. If Washington successfully positions itself as a global energy supplier, Saudi Arabia may hesitate to use its already undercut oil leverage against the US for fear of accelerating an American disengagement from the region.

His [Trump’s] decision to withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement — again — signals to the world that the US is doubling down on fossil fuels, even as global climate experts warn of the catastrophic consequences of continued oil and gas extraction.

However, Saudi Arabia also faces pressure to diversify its economic alliances. China, now its largest trading partner, is keen to pay for oil in RMB, which could undermine the petrodollar system. If Riyadh shifts toward greater economic engagement with China, it could trigger a financial realignment that further weakens US economic dominance. In this scenario, the US might respond with more aggressive foreign policy moves in the Middle East, further withdrawing its military presence in the region and unilaterally favouring an Israel-dominated regional scenario.

Another paradox brought by East Asia’s energy realignment with the US is their climate commitments. While the Biden administration oversaw record US fossil fuel production despite its climate commitments, Trump has made it clear that environmental concerns will take a backseat to energy expansion. His decision to withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement — again — signals to the world that the US is doubling down on fossil fuels, even as global climate experts warn of the catastrophic consequences of continued oil and gas extraction.

This creates a paradox for East Asian players. While they are eager to secure stable energy supplies, they are also facing domestic and international pressure to meet climate targets. Japan, South Korea and Taiwan have all pledged to transition toward renewable energy in the coming decades. Yet by deepening their reliance on US fossil fuels, they risk delaying this transition and facing diplomatic consequences from climate-conscious allies in the European Union and beyond.

In the end, America’s energy pivot is more than just an economic policy — it is a strategic play with profound implications for international relations.

The geopolitical landscape is shifting in unpredictable ways. East Asia’s move toward US energy imports may ease trade tensions but risks straining relationships with longstanding energy suppliers in the Middle East. Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia must navigate its competing interests — maintaining ties with Washington while preparing for a potential economic realignment with China. And as the US aggressively expands its fossil fuel exports, the climate crisis looms larger, adding another layer of complexity to an already volatile global energy market.

In the end, America’s energy pivot is more than just an economic policy — it is a strategic play with profound implications for international relations. Whether this shift stabilises or disrupts global power dynamics remains to be seen, but one thing is certain: the consequences will extend far beyond oil and gas.