[Big read] The first shot Taiwan hopes never to fire

Under mounting military pressure, Taiwan may be pushed to fire a warning shot it hopes never to take — an act that could give Beijing its pretext for war and test America’s commitment. Lianhe Zaobao journalist Miao Zong-Han finds out more.

On 29 December 2025, as people in Taiwan were still immersed in the festive mood following Christmas and preparing to welcome the New Year, the Eastern Theater Command of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) abruptly announced military exercise Justice Mission 2025. The drills involved forces from the ground, naval, air, and rocket forces, and were conducted in the Taiwan Strait as well as in the northern, southwestern, southeastern, and eastern sea and airspace surrounding Taiwan, instantly ratcheting up tensions across the Taiwan Strait.

A closing military ring

During the exercise, the PLA designated restricted navigation zones in five sea and air areas around Taiwan’s main island, and on the second day of the drills carried out long-range joint live-fire exercises. Taiwan’s military assessed that the scope of all five exercise zones encompassed Taiwan’s 12-nautical-mile territorial waters and airspace.

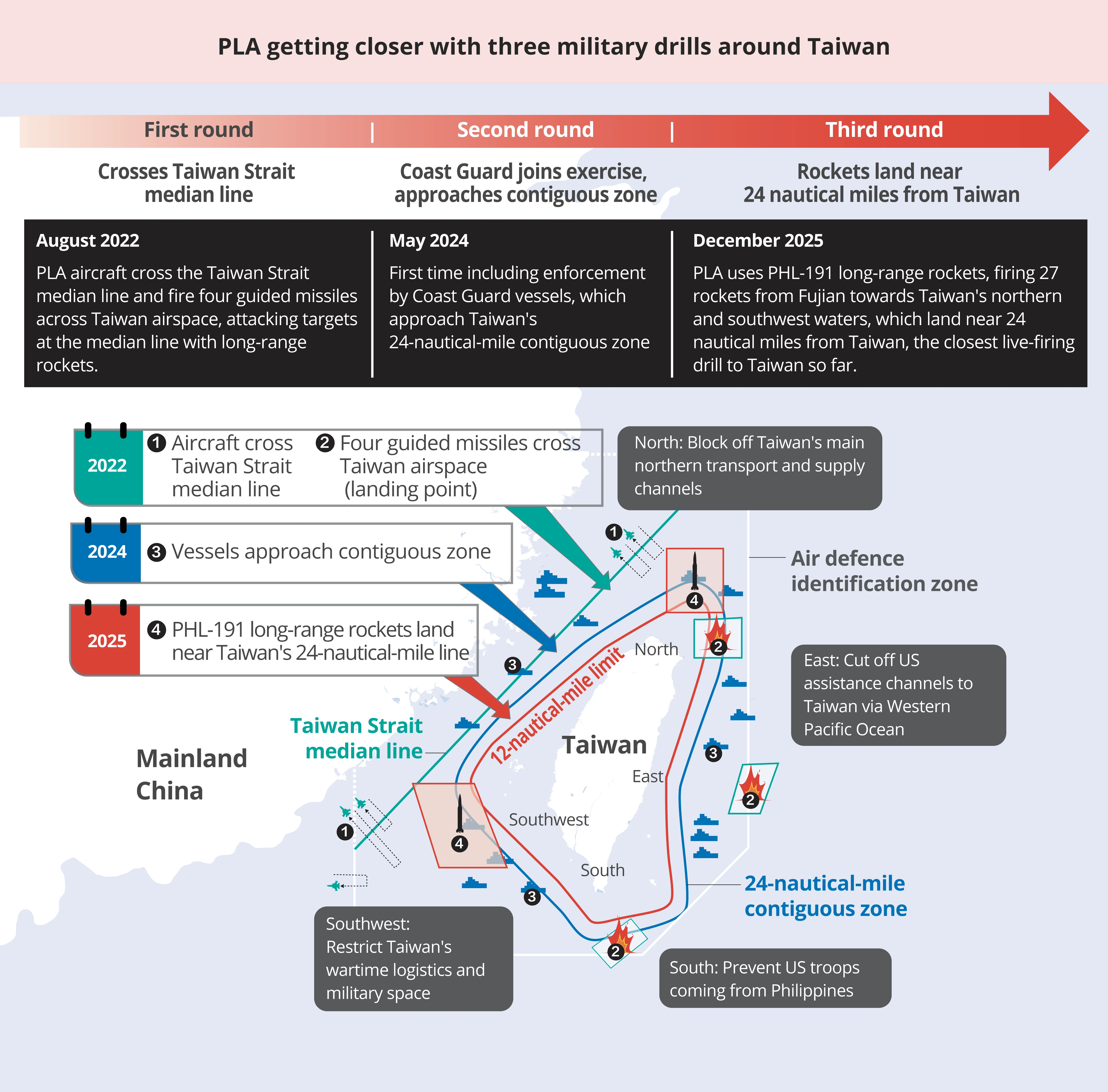

This is the closest that the PLA has come to Taiwan since August 2022, when it conducted its first large-scale encirclement drills in response to then US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan.

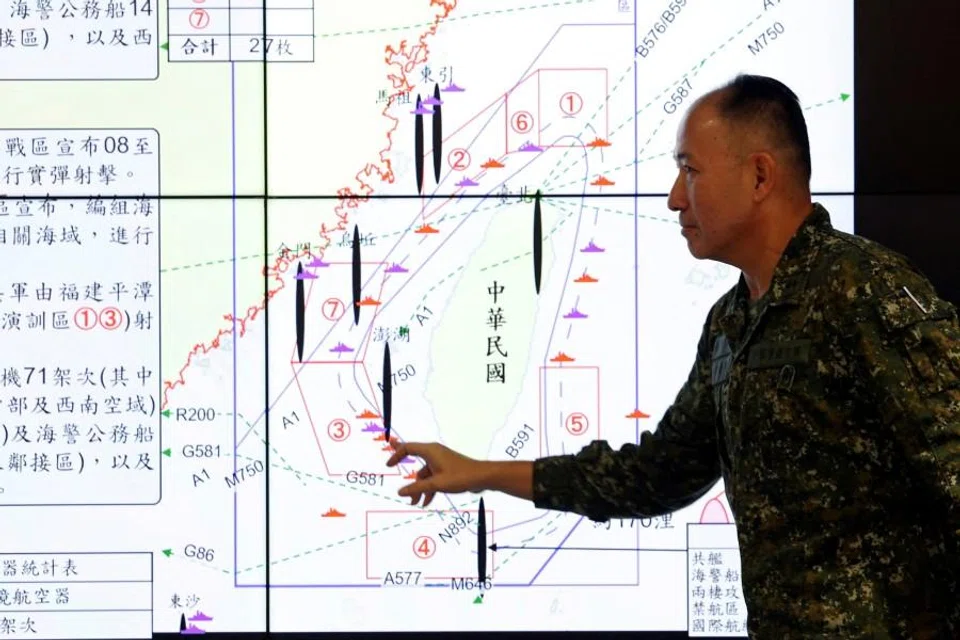

Following the drills, Lieutenant General Hsieh Jih-sheng, the MND’s deputy chief of general staff for intelligence, confirmed that the PLA had used PHL-191 long-range modular rocket artillery to launch a total of 27 rockets in two waves from Fujian toward waters north of Taiwan and off its southwest coast, with the impact points close to Taiwan’s 24-nautical-mile contiguous zone. He said, “That was the closest that PLA rockets have ever come to Taiwan”, adding that Beijing was signalling its intention to “treat the Taiwan Strait as its domestic waters” while testing Taiwan’s military red line.

... when the PLA enters the above-mentioned zones under the guise of exercises, Taiwan faces a dilemma: an overly forceful response risks being portrayed as “provocative”, while an overly restrained response risks the erosion of effective jurisdiction.

A look at the PLA encirclement drills around Taiwan over the past three years shows a steady escalation in Beijing’s power projection. In August 2022, the PLA broke through the median line of the Taiwan Strait; in May 2024, for the first time incorporated China Coast Guard vessels into the exercises and pushed operations close to Taiwan’s 24-nautical-mile contiguous zone; by the end of 2025, live-fire exercises had again pressed up against the 24-nautical-mile line.

There are different layers of legal and military implications when it comes to the waters and airspace surrounding Taiwan.

Median Line not a boundary under international law

First, the median line of the Taiwan Strait is not an international legal boundary. Rather, it is a tacit military understanding formed during the Cold War, long used to prevent direct contact between military forces from both sides in the middle of the strait. However, since then US House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s visit to Taiwan in 2022, the PLA has crossed this line in almost every subsequent exercise, widely seen as a sign that the tacit understanding has broken down and that the risk of conflict has risen.

An air defence identification zone (ADIZ), meanwhile, is a unilaterally designated early-warning airspace established by individual states. It does not constitute sovereign airspace, and entry into it is not in itself illegal, but it can impose operational and psychological pressure by triggering heightened alertness. Under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), a state may also claim a contiguous zone — extending up to 24 nautical miles beyond its territorial sea baseline — within which it may enforce laws to prevent and punish violations related to immigration, public health, customs, and similar matters.

(Bottom left) Military equipment of the ground forces takes part in long-range live-fire drills targeting waters south of Taiwan, from an undisclosed location in this screenshot from a video released by the Eastern Theater Command of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) on 30 December 2025. (Eastern Theater Command/Handout via Reuters)

(Right) Helicopters on an amphibious assault ship take part in military drills in waters southeast of Taiwan, in this screenshot from a video released by the Eastern Theater Command of China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA), on 29 December 2025. (Eastern Theatre Command/Handout via Reuters) (Graphic: Chen Ruiqin)

Therefore, when military aircraft, vessels, or even firepower projection enter this zone, such actions carry a strong implication of asserting jurisdiction.

As for the 12-nautical-mile territorial sea, it is generally regarded as part of a state’s sovereign territory, equivalent to an extension of land territory. If foreign military aircraft or warships enter this area, or if live munitions land within it, such acts would be seen as an infringement of sovereignty and could trigger the right of self-defence.

However, given the complexity of cross-strait relations, when the PLA enters the above-mentioned zones under the guise of exercises, Taiwan faces a dilemma: an overly forceful response risks being portrayed as “provocative”, while an overly restrained response risks the erosion of effective jurisdiction.

... because the details of the military’s rules of engagement are typically not made public, it remains difficult for outsiders to determine under what circumstances Taiwan would judge that the threshold for “opening fire” has been reached.

In June 2025, Taiwan’s Defence Minister Wellington Koo said that if the PLA were to attack Taiwanese aircraft, vessels, or facilities; strike Taiwan’s main island or its outlying islands; or enter Taiwan’s 12-nautical-mile airspace or territorial waters without authorisation, he could order the military to exercise the right of self-defence and carry out proportionate defensive countermeasures.

As a result, during the PLA’s encirclement drills around Taiwan late last month, Taiwan’s military confirmed that it would authorise frontline combat units — including the Navy’s 62nd Task Force, the Air Force Operations Command and theatre commands — to respond in accordance with the level of threat posed by enemy activity, following established rules of engagement and an authorisation matrix.

However, because the details of the military’s rules of engagement are typically not made public, it remains difficult for outsiders to determine under what circumstances Taiwan would judge that the threshold for “opening fire” has been reached.

How Taiwan might activate self-defence

As for how Taiwan’s military would respond if PLA warships were to continue closing in on its territorial waters, Chieh Chung, an adjunct associate research fellow with Taiwan’s Institute for National Defense and Security, told Lianhe Zaobao that the Taiwanese military would not make “opening fire” its first option. Instead, it would initially adopt controlled, gradually escalating interception measures. “If PLA warships cross the contiguous zone and continue advancing toward territorial waters, our military will act before they reach territorial waters.”

“If they enter within 12 nautical miles and keep advancing, then we would consider the question of opening fire.” — Chieh Chung, Adjunct Associate Research Fellow, Institute for National Defense and Security, Taiwan

Chieh explained that the more likely initial steps would include issuing warnings, broadcasting messages, and deploying naval vessels to shadow the PLA ships, blocking them off and forcing them to turn back. If the opposing vessels fail to comply and persist in advancing, subsequent measures would be progressively escalated. Only when they actually enter the 12-nautical-mile territorial sea and continue moving forward would the situation enter the critical threshold of deciding whether to open fire. “If they enter within 12 nautical miles and keep advancing, then we would consider the question of opening fire.”

He emphasised that even if shots were fired, the Taiwanese military would likely not immediately attack the opposing aircraft or vessels themselves, but would instead fire warning shots toward nearby sea or airspace. However, Chieh acknowledged that while ship movements and sea space are relatively easier to control due to slower speeds, similar situations in the air would be far more volatile. Aircraft manoeuvre rapidly, making it difficult to distinguish between warning shots and actual attacks, and the risk of a mishap would be significantly higher.

Based on past observations, Chieh Chung believes that PLA warships do show a trend of continuing to press closer. “These actions in themselves are a form of declaration,” he said, signalling that “Taiwan has no right to exercise jurisdiction over the Taiwan Strait.” At present, however, such manoeuvres are still mainly confined to closing in on the 24-nautical-mile line. As for military aircraft, while they may deliberately cross Taiwan’s restricted airspace, after crossing they generally fly along routes roughly parallel to the median line of the Taiwan Strait, heading north or south, and rarely make a deliberate move into the contiguous zone.

On this basis, Chieh infers that the PLA is still deliberately seeking to avoid accidents or collisions, and therefore is unlikely in the short term to go so far as to enter the 12-nautical-mile zone, “because that would be tantamount to initiating combat”. He cautioned, however, that Beijing’s pressure along the edge of the contiguous zone will continue to be used as a tool of political coercion and lawfare, or legal warfare.

Taiwan must seek high ground as grey zone pressures mount

Responding to the widespread instinctive assessment that the “exercise zones moving closer” should be read directly as a trend of “actual forces moving closer”, Drew Thompson, former US Department of Defense official and now a senior fellow at Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS), told Lianhe Zaobao in an email interview that propaganda certainly paints PLA operations as compressing and squeezing Taiwan, but declared exercise zones and propaganda graphics are not the same as actual deployments of aircraft and vessels.

He added that while the PLA continues to sustain increasing political pressure, there is no clear evidence that “operational patterns have changed significantly”. However, grey zone dangers remain because the space for interpretation is very much compressed, forcing Taiwan to make snap judgements. “Grey zone” refers to the blurring of the line between peace and armed conflict, causing uncertainty.

Yet if Taiwan were to carry out warning shots or forcibly expel the other side “before the opponent fires first”, would Beijing seize the opportunity to construct a narrative that “Taiwan fired first”?

Thompson added that Taiwan has sophisticated surveillance and air defence systems, so the likelihood of a surprise attack is small. Relative to the speed that modern weapon systems travel, the distances between China and Taiwan are short, so Taipei has little time to make decisions how to respond to air and sea incursions.

Yet if Taiwan were to carry out warning shots or forcibly expel the other side “before the opponent fires first”, would Beijing seize the opportunity to construct a narrative that “Taiwan fired first”? Such questions have been discussed with increasing frequency in Taiwan’s military and strategic circles in recent years. Faced with an increasingly severe grey-zone dilemma, activating self-defence mechanisms at the very first instance without being seen as initiating provocation has already become an unavoidable issue for Taiwan.

Clarifying rules of engagement to justify firing first

Dr Sung Wen-Ti, non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub, told Lianhe Zaobao when interviewed that Taiwan should, where possible, “let law enforcement units such as the Coast Guard Administration take the lead in responding to incidents to avoid being accused of firing the first shot”.

However, Dr Sung cautioned that this approach depends on Taiwan making its rules of engagement and external communication much clearer. He said: “Taiwan must clarify its rules of engagement for effective communication, so that there is clarity within the global community when attributing the responsibility for an outbreak of hostilities.”

Dr Lin Ting-Hui, former Deputy Secretary-General of the Taiwan Society of International Law, told Lianhe Zaobao that international law and rules are often treated as tools and weapons in real-world politics. Taiwan, he argued, should all the more use international legal arguments to “guard against China (the mainland) encircling and attacking Taiwan through international legal narratives”, and seek the high ground in opinion warfare and legal warfare, thereby encouraging greater willingness from the international community to intervene and offer support.

Dr Lin believes that before war or armed conflict breaks out, legal warfare and opinion warfare are often crucial preludes for securing international backing and raising the costs for the other side.

Therefore, from Taiwan’s perspective, the narrative surrounding the “first strike” in international public opinion and legal battles should not be narrowly reduced to “who fired the first shot”. Instead, it should return to the question of “who first committed an act that constitutes a violation or improper conduct under international law”. If the other party’s actions already meet such criteria, then Taiwan’s proportionate countermeasures or self-defence actions are, in nature, an exercise of the right of self-defence, rather than a case of “being in the wrong simply because it fired first”.

Would the US worry that Taiwan had “fired first” and thereby undermined crisis management? Would it recognise the legitimacy of Taiwan’s self-defence? These are unavoidable questions Taiwan must confront when making defence decisions.

US opinions if Taiwan fires first

Beyond Beijing’s military coercion, the increasingly restrained posture of US foreign policy in recent years has arguably become Taiwan’s most difficult external variable.

In particular, with the Trump administration’s revival of the “Monroe Doctrine” (restoring US preeminence in the western hemisphere) and cross-border capture of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro signalling a national security strategy more heavily focused on the western hemisphere, questions arise over how Washington would view Taiwan’s actions if it were to conduct defensive fire or take tougher measures in response to PLA forces closing in. Would the US worry that Taiwan had “fired first” and thereby undermined crisis management? Would it recognise the legitimacy of Taiwan’s self-defence? These are unavoidable questions Taiwan must confront when making defence decisions.

In an email reply, Drew Thompson, who was former director for China, Taiwan and Mongolia in the US Office of the Secretary of Defense, emphasised that Taiwan has made clear that it will not fire first and will not antagonise or threaten China, and that Beijing is the only party using military coercion and threatening violence, so there is no doubt in Washington that Beijing is the aggressor.

US emphasis on strategic control

Drawing on the logic of strategic ambiguity, Dr Sung added that the US is concerned not only about legal principles but also about maintaining its strategic control of the situation. He said: “As long as Taiwan’s decisions can be reasonably explained as self-defence and do not undermine US strategic control, whether Taiwan fires the first or second shot is a technical detail and not the most critical issue.”

This suggests that, from Washington’s standpoint, whether Taiwan can frame its actions as necessary, proportionate, and controllable self-defensive responses — and whether those actions align with US crisis-management objectives — may be more important than literal debates over “first strike versus second strike”.

Looking at the Justice Mission 2025 drills at the end of 2025, Beijing’s approach has gone beyond firepower and force deployment to encompass narratives and rule-setting as well. On the one hand, it has combined the designation of exercise zones, long-range live-fire launches, and coast guard law-enforcement operations to send a political signal that it treats the Taiwan Strait as “internal waters”. On the other hand, through grey-zone pressure, it has gradually pushed Taiwan toward a critical point at which it feels compelled to respond, turning the abstract notion of a “first strike” into a concrete, real-world dilemma.

If, in the future, the PLA continues to edge closer to the 12-nautical-mile limit under the guise of exercises, the true challenge of the “first strike” may not lie in the slogan of “whether to fire the first shot”, but rather in whether Taiwan can integrate military responses, legal legitimacy, and international communication into a coherent crisis-management framework — one that is executable, persuasive, and controllable.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “台军临近关键时刻 或被迫按下防卫“第一击””.