The China factor in Indonesia’s BRICS ambition

China’s influence and geopolitical clout drive Indonesia’s interest in the BRICS grouping. Yet Indonesia must balance opportunities and constraints, ensuring that BRICS membership does not imply economic alignment, says Indonesian researcher Muhammad Habib Abiyan Dzakwan.

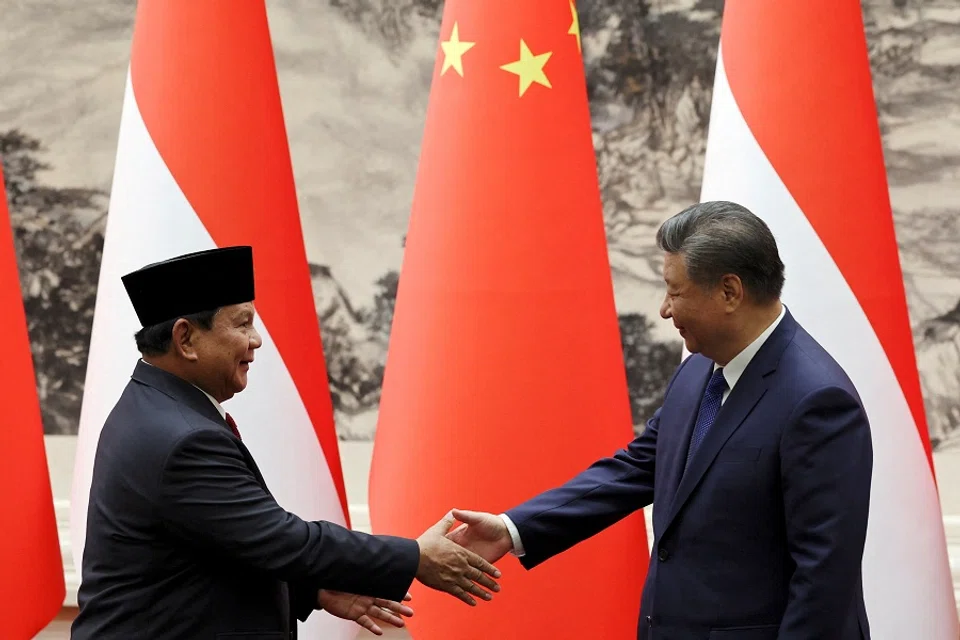

After Indonesia inaugurated President Prabowo Subianto last month, one of the new administration’s first foreign policy moves was to announce the country’s intention to pursue a full-fledged BRICS membership. BRICS is a geopolitical club that began as BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India, China) and later became BRICS with the addition of South Africa. Iran, United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt and Ethiopia joined as new additions in early 2024 and at the BRICS summit in Kazan, Indonesia was among the 13 countries made “partner countries”.

At the summit, the newly appointed Indonesian Foreign Minister Sugiono said that Indonesia’s BRICS membership is aligned with Indonesia’s free and active foreign policy doctrine, domestic priorities of Prabowo’s presidency, as well as the country’s aspiration of advocating the global south’s agenda. While such an argument is up for discussion, one question for Indonesia remains: what can and can’t the country get from joining BRICS as a member? This piece argues that the China factor offers some explanation.

China does not impose the same upfront conditions on developing countries when offering development assistance and foreign direct investment...

What can Indonesia get?

Among various rationales explaining why interest in BRICS membership continues to grow, the presence of China stands up as an influential one. It is not necessarily China’s active campaign that makes it so, but the charm comes from the geopolitical and geoeconomic weight Beijing carries.

Emerging economies like Indonesia are often tempted to rapidly advance their development while minimising political costs. Indonesia wants to become a developed country but implementing multipronged reforms is often daunting for the ruling government, which relies on political and economic concessions to maintain domestic stability. This is where China and BRICS perhaps make the difference.

China does not impose the same upfront conditions on developing countries when offering development assistance and foreign direct investment, despite having undergone significant reforms since 1978. While terms may be adjusted throughout the process, Beijing’s approach is to invest first.

This engagement style is appreciated by Indonesian politicians who need campaign ammunition such as job opportunities and growth for their re-election bids. These politicians also deprioritise domestic reforms as they are worried about the upfront cost and the inability to claim credit, as benefits often emerge long after their tenure.

This situation, along with China’s respect for local contexts, apparently grants any group where China is a member, including BRICS, greater sympathy from developing economies. However, the risk of complacency toward poor governance practices is significant and must not be discounted.

China and BRICS members also refrain from naming and shaming others for not being able to conform to specific standards. The group neither attempts to position itself on a higher moral ground nor lectures non-members about geopolitical moves as if others lack the agency to comprehend the situation.

The group offers an opportunity to establish new norms that better serve the interests of the global south. Although those norms might not be legally enforceable even among BRICS members, they tell the world that the voices of the weaker powers matter. As a post-colonial country, Indonesia is attracted to any chance to redress grievances with the international system, as the country has always done since the 1955 Asian-African Conference.

By far, China does not force BRICS members and other countries to choose between its institutions or the Bretton Woods system.

Moreover, China’s enormous economic power injects credentials into BRICS-affiliated financial institutions such as the New Development Bank (NDB) and the Contingent Reserve Arrangement (CRA). Combined with the capacity of the newly recruited wealthy nations like the UAE, these institutions emerge as attractive supplementary funding to answer the tremendous development needs of the global south.

By far, China does not force BRICS members and other countries to choose between its institutions or the Bretton Woods system. China signals understanding that its partners get the right to participate in both institutions as their development financing needs go beyond what might be available.

For Prabowo’s administration, which plans to roll out many welfare programmes and improve Indonesia’s defence posture, this is an offer it cannot afford not to be tempted by.

BRICS is not able to grant Indonesia the required credentials to capture more investment from Western companies.

What can’t Indonesia get?

As much as the China factor lures Indonesia to secure full-fledged BRICS membership, ceilings exist as to what the country can actually get from it. No matter how convenient the safe space offered by China through and beyond the group, BRICS is not able to grant Indonesia the required credentials to capture more investment from Western companies.

The BRICS membership was not intended to assess whether an economy is favourable for business; that role is typically fulfilled by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). Therefore, Indonesia’s BRICS membership should not hinder its accession process to the OECD.

The China factor in BRICS also cannot shield Indonesia’s economy from geopolitical headwinds amid great power rivalries. As the second-term presidency of Donald Trump is on the horizon, it appears more likely than not that the US will intensify its economic statecraft against China.

Former President Trump promised to impose 60% tariffs towards China’s products and 10% universal tariffs for foreign countries. He boasted another harsh tariff punishment for countries decoupling from the dollar in their international transactions, a prospect that was pitched by a certain caucus within BRICS.

Regardless of whether Washington’s tariff plan is viable, it is uncertain how effectively BRICS can coordinate a collective response to mitigate the impact. Indonesia should not underestimate President Trump’s determination to compete with China and the group.

... there is no indication that China treats BRICS members as more special than others.

Moreover, there is no guarantee that China would allocate exclusive economic privileges for BRICS members. As much as it embraces the economic liberalisation agenda, China understands the conundrum of advancing intra-BRICS trade agreements, investment treaties or cooperative visa regimes when mutual caution and suspicions linger.

By far, bilateral channels likely remain China’s preferred way to transact and mobilise capital with the other BRICS members, offering little added value to Indonesia’s full commitment to the group. Additionally, there is no indication that China treats BRICS members as more special than others.

Its unilateral free visa policy is the latest example to back the argument. Instead of extending the policy to BRICS members and outreach partners, China focuses more on attracting tourists from higher-income countries. At the end of the day, BRICS is still a group of emerging economies which would likely compete with Indonesia over the same pool of influence or resources.

Prabowo’s administration must urgently reassure partners, through both words and actions, that Indonesia’s membership in the group does not signify economic alignment or support for revisionist ambitions.

What does Indonesia want?

As the China factor offers both opportunities and constraints to Indonesia’s BRICS strategy, the crucial next step is to leverage the current momentum while avoiding geopolitical repercussions, especially if withdrawing the intention to join BRICS is no longer feasible. Prabowo’s administration must urgently reassure partners, through both words and actions, that Indonesia’s membership in the group does not signify economic alignment or support for revisionist ambitions.

To that end, Indonesia needs to explain what agenda it wants to push within and through the group, as well as the strategy for advancing it. Such clarity would hopefully answer any confusion about whether Indonesia departs from its longstanding non-aligned foreign policy.