China's 'hegemony with Chinese characteristics' in the South China Sea

Though in word it professes to never seek hegemony or bully smaller countries, in deed, China behaves unilaterally and flexes its economic and political muscles for dominance in the South China Sea, says Indian academic Amrita Jash.

On 22 November 2021, at the ASEAN-China Special Summit to Commemorate the 30th Anniversary of ASEAN-China Dialogue Relations, Chinese President Xi Jinping in his speech titled "For a Shared Future and our Common Home" categorically stated: "China will never seek hegemony, still less bully smaller countries." In Chinese politics, "never seek hegemony" has been a standard phrase reiterated by Mao Zedong, Deng Xiaoping and now Xi Jinping.

What is important to note is that theoretically, China has maintained its position, but its actions have failed to match the words. Especially, in the context of Southeast Asia, where China's actions in the South China Sea tells a different story - not of a "shared destiny" but certainly of "hegemony".

What defines a "hegemon"? John J. Mearsheimer in his book The Tragedy of Great Power Politics describes a hegemon as a "state that is so powerful that it dominates all the other states in the system" and "no other state has the military wherewithal to put up a serious fight against it". Here, the keyword is "power" which entails supreme economic and military capabilities.

In view of this, China's economic prowess and its growing military capabilities - as evinced by its defence budget of US$209 billion - pressure other powers (who lack the capabilities) to submit to China and invariably makes China a hegemon. A testament to this is China's growing aggressive and assertive posture, or rather "bullying" in the South China Sea.

Acting like a hegemon

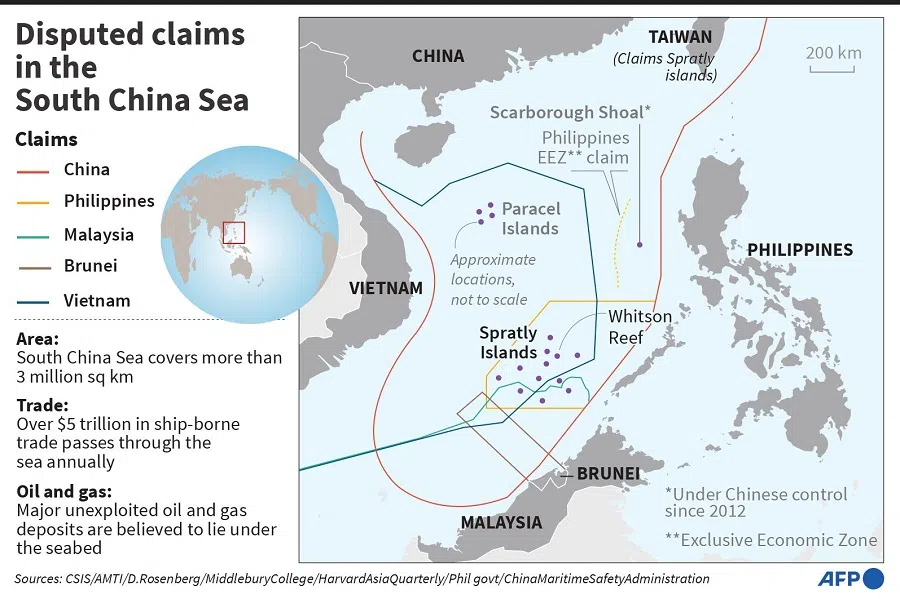

In this case, Chinese hegemony can be understood in terms of Beijing's words and actions to concretise its sovereignty claims under the imaginary "nine-dash line"- as Beijing has failed to clarify its use of the nine-dash line since its inception in 1947 to demarcate its claims over the South China Sea.

To explain, China's narrative on the South China Sea is built on the following claims. In 2009, Dai Bingguo, then state councilor, referred for the first time to the South China Sea as a "core interest"- a term often used for Taiwan, Tibet and Xinjiang. In 2015, Chinese Vice-Admiral Yuan Yubai emphatically stated: "The South China Sea, as the name indicates, is a sea area that belongs to China." Furthermore, President Xi Jinping in his lecture in Singapore in 2015 posited: "South China Sea islands in disputes between China, other claimants have been Chinese territory since ancient times."

Owing to such "historical logic" and being a signatory to the UNCLOS, the Chinese state rationalises its actions under the mandate of "inescapable responsibility to safeguard territorial sovereignty and legitimate maritime rights", as manifested by China's unilateral and defensive actions.

Actions against international law?

In so doing, China has contradicted international laws in five ways:

First, by building artificial islands in the South China Sea and further fortifications in the form of military installations to aid China's anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) strategy.

Second, China has strengthened its fishery enforcement laws, such as in 2013, when the local Hainan Provincial People's Congress approved revised "measures" for fishing in the South China Sea such that foreigners and foreign vessels entering Hainan's claimed jurisdiction need to seek prior approval from the Chinese government.

Third, in 2020, Chinese government announced the establishment of two new administrative structures in the South China Sea: Xisha district, covering the Paracel Islands and Macclesfield Bank, and Nansha district, covering the Spratly Islands - both under the authority of the local government in Sansha, Hainan province.

Fourth, in 2021, China passed the new Chinese Coast Guard Law that authorises its maritime law enforcement fleets to use lethal force on foreign ships operating in China's waters which includes the disputed waters claimed by China, such as the South China Sea.

And fifth, China conducts deep sea surveys in the South China Sea as witnessed in the presence of survey vessels off the coasts of Malaysia, Indonesia, Philippines, and Vietnam - a pressure tactic to monitor submarine traffic in the disputed waters and assert its claims.

By such measures, China is practicing a denial strategy which has greater impact than that of inflicting direct punishment on other claimant states. What adds to it is the Chinese strategy of "salami-slicing"- territorial expansion in a "bit-by-bit" manner.

With its unilateral actions, China has changed the status quo in the South China Sea to an extent that the territorial and maritime dispute is no more a regional issue but a global concern.

What further adds to the "hegemony" aspect is China's defiance of the 2016 South China Sea arbitration that decided in favour of Philippines by rejecting China's claims to the South China Sea based on the "nine-dash line" map and specified that there was "no legal basis for any Chinese historic rights". China said in response that the award is "null and void and has no binding force" and that "China neither accepts nor recognises it", in a further defiance of international laws.

With its unilateral actions, China has changed the status quo in the South China Sea to an extent that the territorial and maritime dispute is no more a regional issue but a global concern.

By creating its own territorial supremacy against America's offshore balancing, China's military disposition in the South China Sea is equivalent to coercive diplomacy wherein any defiance (from the other claimants) can levy severe costs and compliance can result in benefits (under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and others).

Countries like Vietnam, Philippines and Indonesia have raised their concerns over China's growing military activism in the South China Sea. For instance, in 2017, Indonesia renamed the northern reaches of its exclusive economic zone in the South China Sea the North Natuna Sea while Vietnam in 2019 issued warnings to initiate international arbitration against China - a pushback against China's maritime and territorial ambitions.

In addition, the US too has stepped up its freedom of navigation operations and aerial patrols over the South China Sea to challenge and contain China's unilateral actions.

This only proves that while China would want to believe its actions in South China Sea as part of "shared destiny", its actions can be best defined as that of practicing hegemony with what Beijing likes to call "Chinese characteristics". Therefore, if China and ASEAN succeed in finalising the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea, it will likely be a one-way street - undoubtedly the "Beijing way".

Related: Should China station fighter jets in the South China Sea? | SEA states have few options to mitigate escalating South China Sea tensions | Apart from ASEAN and China, international community and law are part of South China Sea discourse | Second Thomas ShoaI: Is China bullying its smaller neighbours in the South China Sea? | Indonesia crosses swords with China over South China Sea: 'Bombshell to stop China's expansionism'? | What has changed in China's South China Sea policy under Xi Jinping?

![[Big read] China’s 10 trillion RMB debt clean-up falls short](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/d08cfc72b13782693c25f2fcbf886fa7673723efca260881e7086211b082e66c)