China’s overtures to Southeast Asia: Xi takes the lead

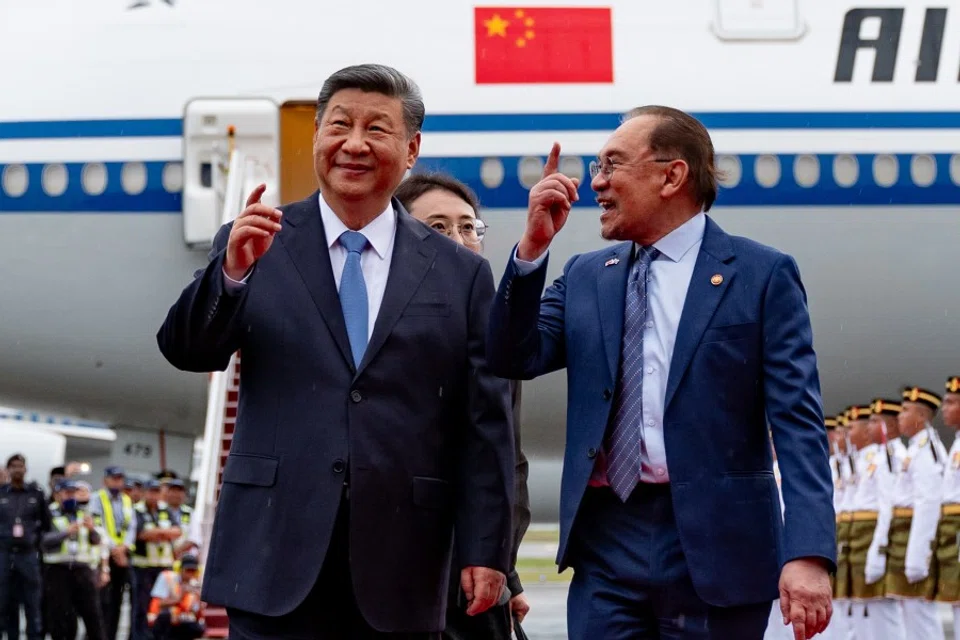

Chinese leader Xi Jinping has taken a personal interest in driving high-level visits to Southeast Asia. This reflects the region’s growing importance and Beijing’s bid to manage global uncertainty.

Several Southeast Asian leaders are likely to attend China’s 80th Second World War victory anniversary parade in Beijing on 3 September. The higher seniority of spectators in 2025 compared to the 70th anniversary parade in 2015 is a testament to the region’s growing ties with China. This article contributes some hard data on bilateral interactions to examine the politics behind Beijing’s uneven yet developed attention to the region.

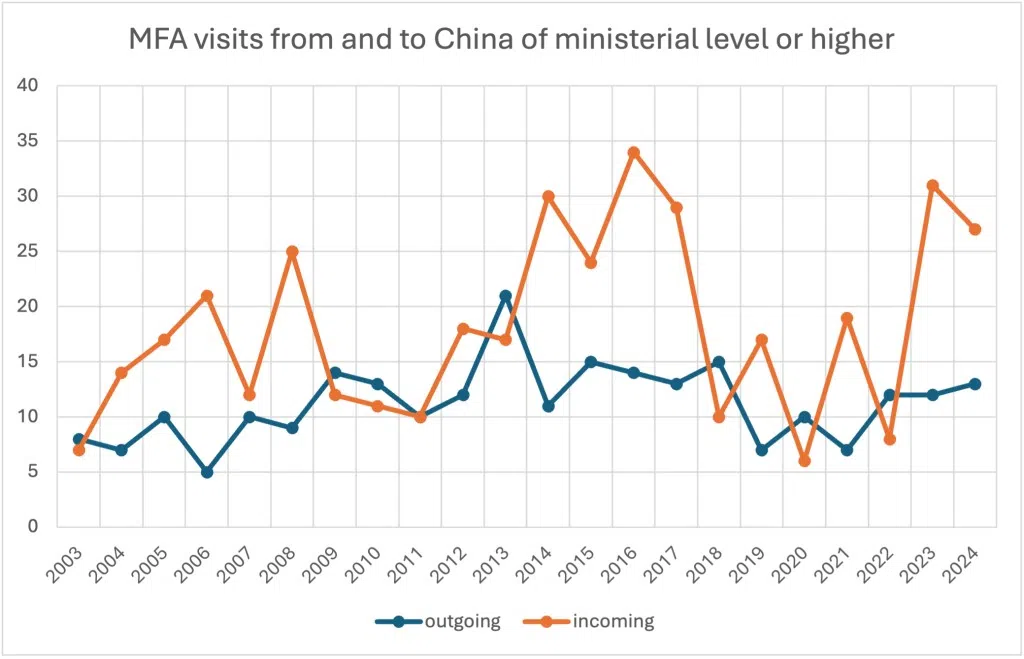

Using announcements on the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) official website, I built a database covering the presidencies of Hu Jintao (2003–2013) and Xi Jinping (2013–present). An analysis of ministerial-level or higher visits to Southeast Asia shows that Xi Jinping is playing a bigger diplomatic role.

After becoming president in 2013, Xi himself initially became the most frequent visitor to Southeast Asia...

This development can be explained by the New Era of Xi, in which China’s paramount leader shapes foreign policy more directly. Xi Jinping’s Thought on Diplomacy provides a personal role for the general secretary presiding over “the top-level design and strategic planning of China’s diplomatic work”. In 2013, Xi signalled a stronger focus on China’s neighbourhood with the first Central Peripheral Diplomacy Work Conferences ever.

Higher diplomatic traffic

After becoming president in 2013, Xi himself initially became the most frequent visitor to Southeast Asia behind his foreign ministers and before Prime Minister Li Keqiang. Following his first two terms, the aged leader could take more of a backseat, having placed his own people in key functions. In his third term so far, Xi has let new Prime Minister Li Qiang take second place as he delegates more tasks to his more trusted subordinates. This returns to the division of labour of the Hu period.

We can observe Xi’s ideas about “peripheral diplomacy” already in his early attention to Southeast Asia. As vice president (2008–13), his six visits to the region ranked him above President Hu’s three. Figure 1 shows the increase in diplomatic traffic from Southeast Asia to China after Xi took office, as well as an initial burst of outgoing traffic from China.

Xi’s peripheral diplomacy towards Southeast Asia does not mean all neighbours get equal attention.

Under Xi, leader trips to Southeast Asia and South Asia have doubled compared to Hu. Presidential attention for Central Asia has remained constant at a high level. The decline in Chinese high-profile visits to Northeast Asia is likely related to the complicated relations with that region. The fact that Xi has still visited the European Union more often than Southeast Asia seems less telling about Beijing’s focus when considering that there are more EU member states (27) than countries in ASEAN (10).

Xi beats Hu on visit stakes

Regional ‘nodes’ get more attention

Xi’s peripheral diplomacy towards Southeast Asia does not mean all neighbours get equal attention. All Southeast Asian countries except Brunei have received more visits from China in Xi’s 2.5 terms compared to Hu’s 2. Four countries stand out, however, for their substantial increases: Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, and Vietnam.

Indonesia’s continuing position as the top destination for Chinese visits reflects its centrality within ASEAN. Singapore is a regional hub that presents itself as a neutral bridge between the East and West. Malaysia has become more important to court as domestic political shifts and the changing geopolitical circumstances have made it a more active player. This also applies to Vietnam.

Beijing’s realist diplomatic and economic logic explains this selective increase in outgoing attention. Xi Jinping’s Thought on Diplomacy looks to bigger countries and effective powers for the capability and responsibility to manage the regional order. The countries mentioned have meanwhile become more economically important for Beijing as China turns to Southeast Asia for natural resources, affordable labour, and continued access to Western markets.

Incoming visits do not burden Chinese senior officials with travel. Hosting incoming visitors also gives face to visitors, making them suitable political rewards.

Looking at incoming visits by Southeast Asian leaders, a more political pattern emerges. Trips to Beijing by officials from Cambodia, Laos, and Indonesia have increased substantially, with a second tier made up of Vietnam, Malaysia, and Myanmar. It shows Beijing’s special consideration for “friends” or countries more politically aligned with China.

There is a practical component here. Incoming visits do not burden Chinese senior officials with travel. Hosting incoming visitors also gives face to visitors, making them suitable political rewards. However, the above-mentioned countries stand out due to greater support for Chinese attempts at shaping the international order through initiatives like BRI or BRICS and calling out Western hegemonism and hypocrisy.

Political factors also play a role in the other direction. The Philippines’ weak showing likely reflects the ups and downs in the relationship. After a warmer period under President Rodrigo Duterte and under less China-friendly President Marcos Jr, it is the only Southeast Asian country to not have had a visit to China yet in Xi’s third term.

... China has an interest in stable political and economic ties with its direct periphery. Southeast Asia’s strategic geographical position and developmental potential make it especially important.

Xi’s introduction of peripheral diplomacy has given Southeast Asia greater attention. As Beijing sees the “changes unseen in a century” speed up, better ties with its neighbourhood have become more important. To offset growing global uncertainty, China has an interest in stable political and economic ties with its direct periphery. Southeast Asia’s strategic geographical position and developmental potential make it especially important.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)