Is the ‘China-ASEAN+’ model quietly taking shape?

Successive visits by top Chinese leaders to Southeast Asia reflect the region’s importance to China, says ISEAS researcher Lye Liang Fook, who argues that stronger ties will allow China to burnish its credentials as a reliable partner and counter US influence.

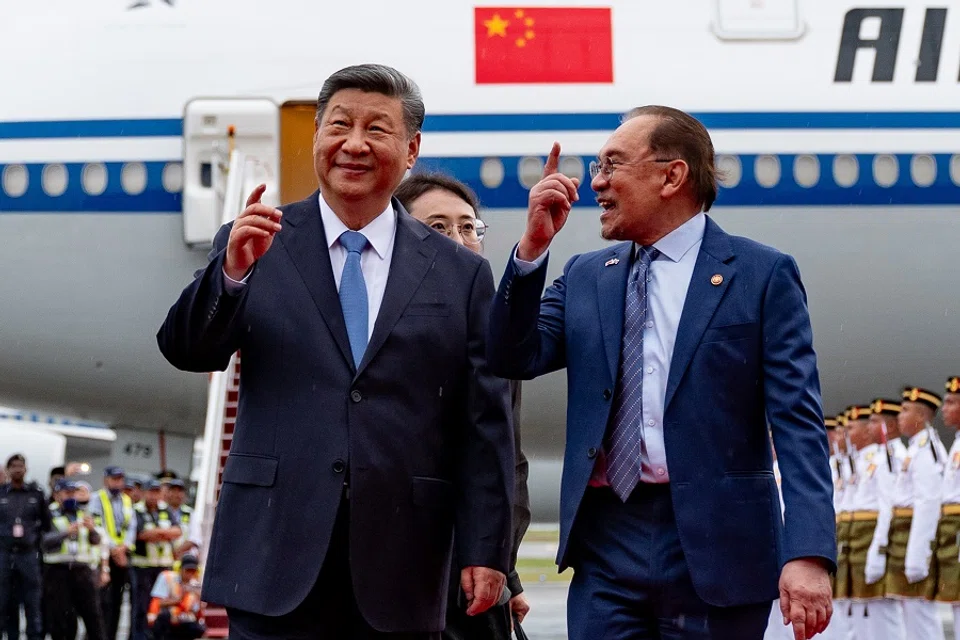

In his first foreign visit of the year, Chinese Premier Li Qiang visited Indonesia and Malaysia in May 2025 — another first that followed the trail set by Chinese President Xi Jinping when he travelled to Vietnam, Malaysia and Cambodia in April 2025. The successive visits by China’s top two leaders to the same region demonstrate Beijing’s concerted efforts to draw Southeast Asia closer and shape an international order that is more aligned with its interests.

Indonesia: China’s gateway to the global south?

Indonesia, Li Qiang’s first stop, is important to China for several reasons. Maintaining good relations with Indonesia — the largest and most influential player in Southeast Asia and ASEAN — strengthens China’s ability to engage the region and the association.

Furthermore, Indonesia has the fourth-largest population and the largest Muslim population in the world, in addition to being a major developing country. Indonesia, therefore, fits neatly in China’s strategy to strengthen its ties with countries in the global south.

Equally significant is Indonesia’s demonstrated support for China’s global initiatives, which enables Beijing to extend its overseas presence. The two countries began building the China-Indonesia Community with a Shared Future in 2024, following their agreement to the joint pact in 2022. In January 2025, Indonesia became the first ASEAN country to join BRICS — a loose configuration of emerging and developing economies with China as a dominant player.

The Jakarta-Bandung High Speed Rail (HSR) is regarded as a flagship project under Beijing’s Belt and Road initiative. During his visit to Indonesia, Li Qiang called on the two countries to build upon such notable joint projects to “further polish the golden brand” of the Jakarta-Bandung HSR.

Beijing hopes Malaysia will focus on strengthening ASEAN-China relations while downplaying differences over the South China Sea — an approach that Malaysia shares.

Malaysia: ASEAN’s bridge to China?

Likewise, Malaysia has similarly shown support for China’s global initiatives. When Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim made the first of his two visits to China in 2023, both countries reached a consensus on building a China-Malaysia Community with a Shared Future.

During his visit, Anwar praised China’s Global Development Initiative, Global Security Initiative and Global Civilisation Initiative. Their signature Belt and Road Initiative project, the East Coast Rail Line, is slated for completion by the end of 2026. Malaysia is among the few ASEAN member states that joined BRICS as a partner country, a rung below Indonesia, which is a full member.

China also values strong ties with Malaysia because the latter serves as ASEAN chair and country coordinator for ASEAN-China dialogue relations from 2024 to 2027. Through these roles, Malaysia helps drive ASEAN’s agenda and shapes how the bloc engages its dialogue partners, especially China. Beijing hopes Malaysia will focus on strengthening ASEAN-China relations while downplaying differences over the South China Sea — an approach that Malaysia shares.

When Anwar met Xi for talks in Kuala Lumpur in April 2025, he told Xi that as ASEAN chair and country coordinator for ASEAN-China dialogue relations, Malaysia would actively promote ASEAN-China cooperation for the benefit of regional peace, stability and prosperity.

Separately, when asked about how ASEAN could show solidarity with the Philippines amid China’s coercion of Manila in its own Exclusive Economic Zone during the 2025 Shangri-La Dialogue, Anwar suggested that tensions between the two countries were somewhat exaggerated, noting that he had seen Philippine President Bongbong Marcos and Li Qiang engaging with each other during the May 2025 ASEAN summit in Kuala Lumpur.

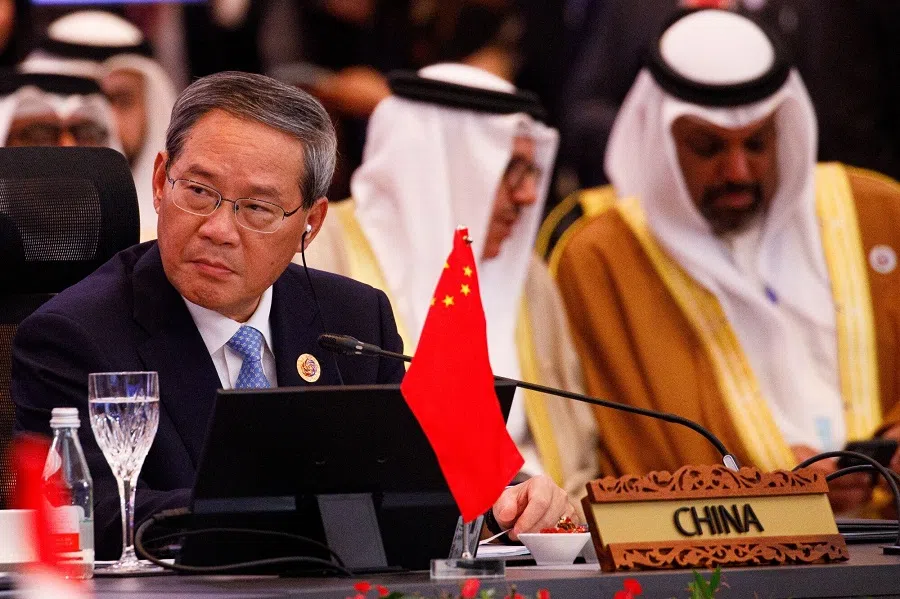

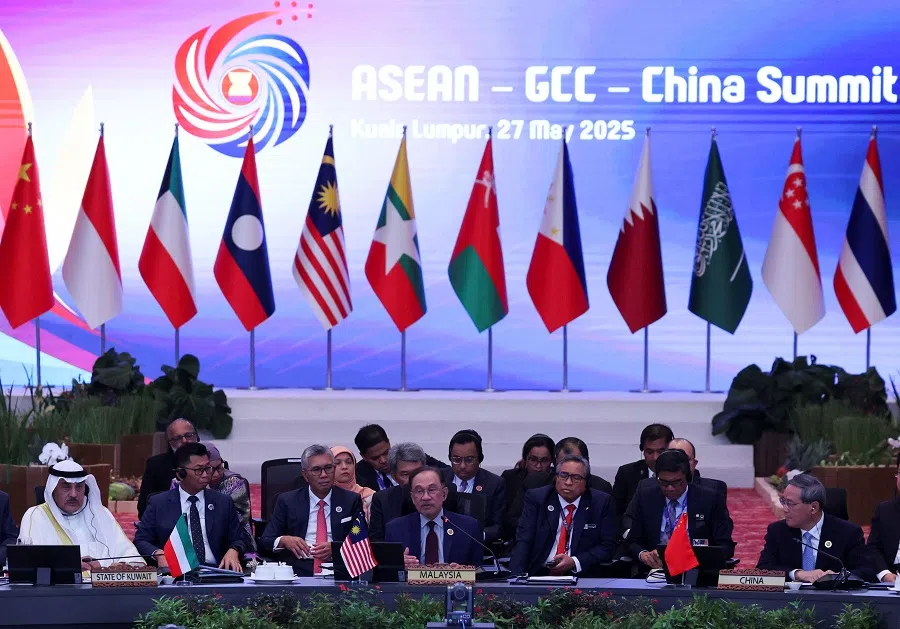

Li Qiang’s participation at the ASEAN-GCC-China Summit shows Beijing’s strong support for a new cooperation model that either excludes the US or constrains America’s global influence.

Countering the US with a new model

More significantly, Li Qiang’s participation in the inaugural ASEAN-Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)-China Summit in Kuala Lumpur indicates Beijing’s support for cooperation models that build linkages with other regions, to counter not only the negative impact of American actions but also US influence.

The primary purpose of Li Qiang’s Southeast Asia visit was to strengthen China’s bilateral ties with Malaysia and Indonesia. In Indonesia, Li brought a business delegation of around 60 people and addressed the Indonesia-China Business Reception, where he expressed optimism about expanding bilateral trade and investment ties.

A total of 12 agreements were signed, including one expanding the use of local currency settlement to capital and financial accounts to reduce reliance on the US dollar. Another agreement granted Indonesia approval to directly export frozen durians to China.

As expected, Li Qiang used his visits to Indonesia and Malaysia to criticise unilateralism, protectionism and acts of bullying by the US. In reference to the 1955 Bandung Conference — where then Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai, together with other Asian and African leaders, endorsed the Five Principles of Peaceful Co-existence, including equality and cooperation for mutual benefit, and peaceful co-existence — Li invoked the Bandung spirit in his address at the business reception. He called on China and Indonesia — both major developing countries and key global south players — to work more closely to promote true multilateralism.

Going further, Li Qiang’s participation at the ASEAN-GCC-China Summit shows Beijing’s strong support for a new cooperation model that either excludes the US or constrains America’s global influence. A widely held economic-centric view is that the summit offers vast opportunities to integrate markets, deepen innovation, and promote cross-regional investment.

There is a Chinese view that ASEAN is transitioning from “ASEAN+”, i.e., a 10+1 or 10+3 cooperation model, to a “China-ASEAN+” cooperation model, with China and ASEAN as the axis and hub.

A ‘China-ASEAN+’ cooperation model?

However, there is a Chinese view that ASEAN is transitioning from “ASEAN+”, i.e., a 10+1 or 10+3 cooperation model, to a “China-ASEAN+” cooperation model, with China and ASEAN as the axis and hub. Under this new framework, China and ASEAN could proactively link up with other countries, regions — the ASEAN-GCC China platform is one example — and international organisations in a new global cross-regional cooperation network.

According to this perspective, a “China-ASEAN+” network based on equality, inclusiveness and non-confrontational institutional cooperation would help to modernise multilateralism, improve regional connectivity, and promote natural and reasonable changes in the world order. Such a network, characterised by interconnectedness among different regions, will also greatly reduce the space for hegemonic countries like the US to behave recklessly. Furthermore, the “China-ASEAN+” network is an institutional response to the collective rise of the global south countries.

Although the above perspective has not been officially endorsed, the fact that it is carried by a publication under the purview of the Communist Party of China suggests that there could be some level of official support for such views.

These views also appear to align with China’s call for global governance to move towards a more just and reasonable direction — one that gives the global south a stronger voice and greater representation. In light of this, and amid continued global uncertainty, China is likely to push for more “China–ASEAN+” networks with BRICS (given that some ASEAN states are already full or partner members), the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), or possibly even the EU.

Within Southeast Asia, China appears to prioritise developing ties with countries that have officially endorsed its global initiatives...

The future of China-Southeast Asia relations

China will continue to focus on developing its ties with Southeast Asia as a key pillar of its neighbourhood diplomacy. Southeast Asia and ASEAN are also important to China in terms of Beijing’s overall strategy to reshape a world order that dilutes US influence.

Within Southeast Asia, China appears to prioritise developing ties with countries that have officially endorsed its global initiatives, as reflected in the rapid succession of visits by Xi Jinping and Li Qiang to Vietnam, Malaysia, Cambodia and Indonesia.