Does the 2024 US presidential election outcome matter to China?

Academic Joseph Liow says that rhetoric aside, it might not be that significant for China whether Donald Trump or Kamala Harris wins the November US elections.

While 2024 may indeed be the year of elections with almost four billion people voting worldwide, it is the US presidential election this November that will be the most widely watched. Not to put too fine a point on it: in our present age of multiple concurrent global crises, this will be a high stakes election not only for Americans, but for the rest of the world.

Historically, foreign policy issues seldom featured prominently in US presidential elections. Of course, there have been exceptions. The year 1968, during the height of the Vietnam War, was one such case. The year 2004, when the global war on terror and the invasion of Iraq took centre stage, was another. For the most part however, it has been domestic issues — principally the economy — that have dominated electoral debates and swayed voters.

This distinction between domestic and foreign however, blurs considerably in the buildup to the 2024 election. To be sure, domestic concerns remain paramount, but if campaign rhetoric is any indication, they have fused seamlessly with political narratives regarding China, specifically, how the latter has apparently stolen American jobs and intellectual property, ergo the need for tariffs and industrial policy. This is certainly not good news for Beijing. Nor is it good news for free trade and globalisation.

China policy: more continuity than change?

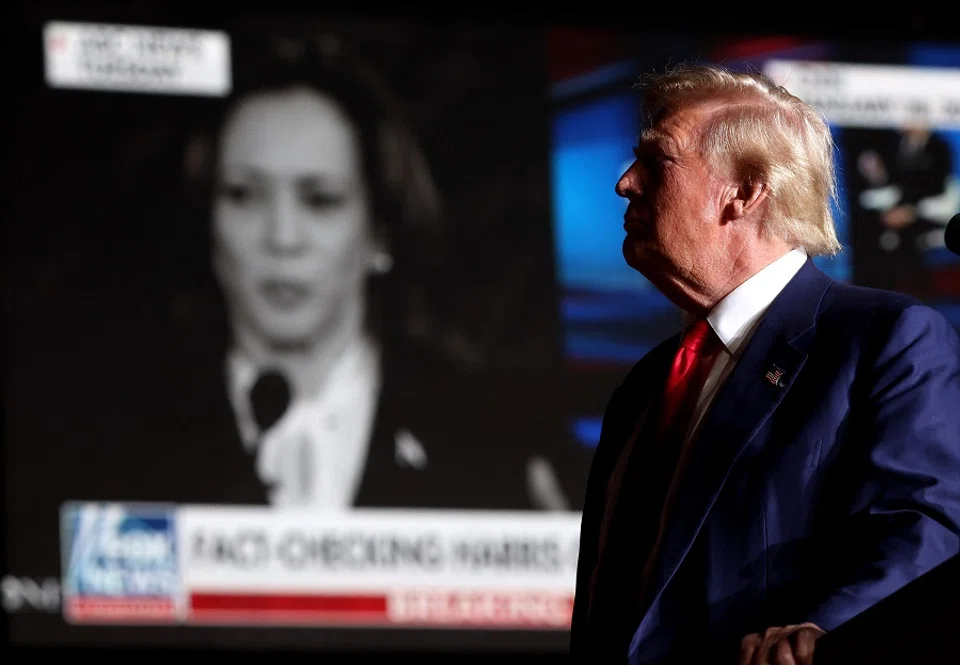

So how might Donald Trump or Kamala Harris, the two protagonists in America’s latest unfolding political drama, approach the China challenge?

Far from the isolationist that some predicted him to be, Trump actually renewed focus on the Asia-Pacific, including renaming it the Indo-Pacific...

In the case of former president Trump, his first four years in office provides some hints. During this period, the Trump administration orchestrated a sharp turn away from the prevailing wisdom of that time, which was cautious optimism about China, towards great power competition.

Trump populated his administration with China hawks who were more than happy to focus on economic interdependence as the source of fundamental frictions, resulting in, first, the trade war, and soon after, the technology war. During this time, Trump embraced a brash and assertive stance towards China, seemingly unperturbed that such an approach was sending bilateral relations spiralling.

Far from the isolationist that some predicted him to be, Trump actually renewed focus on the Asia-Pacific, including renaming it the Indo-Pacific, as an important theatre for US defence interests, and with China squarely in his sights. Regional security allies and partners welcomed a more assertive US posture, but were at the same time discomfited by Trump’s transactional approach even towards them.

Known for the mercurial quality of his presidency, there was nevertheless one thing that was consistent with Trump: his dislike of trade deficits. By this token, should Trump return to the White House, it can be safely assumed that he will once again surround himself with China hawks who are staunch advocates of tariffs. Truth be told, a number from his previous administration — who have not burnt bridges with him — are already waiting in the wings.

A primary difference between the Biden and Trump administrations, and which Harris can be expected to continue, is the former’s preference for proactive diplomacy and the building of international partnerships.

Any effort to try to divine a Harris administration’s approach to China must necessarily begin with an understanding of what she will inherit from President Joe Biden. After all, he is her current boss.

What is striking about the current Democrat administration’s approach to China is not that it had jettisoned policies inherited from the Trump administration. Rather, President Biden and his team have both accelerated but also fine-tuned them. This approach was laid out by Secretary of State Antony Blinken in the early days of the administration, when he described America’s approach to China as “competitive when it should be, collaborative when it can be and adversarial when it must be”.

A primary difference between the Biden and Trump administrations, and which Harris can be expected to continue, is the former’s preference for proactive diplomacy and the building of international partnerships. Whereas President Trump was fond of a transactional and unilateral approach to global affairs, President Biden has invested in partnerships with friends and allies by strengthening the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue (Quad) (which to be fair, was revived during the Trump administration), deepening Japan-South Korea-US trilateral cooperation, enhancing defence ties with the Philippines and initiating AUKUS comprising Australia, the UK and the US.

Meanwhile, Biden also introduced a targeted “de-risking” approach of “small yard, high fence” that focused mostly on restrictions on Chinese access to advanced semiconductor technology and equipment, but has also reinforced this with industrial policies such as the Inflation Reduction and CHIPS Acts designed to revitalise key sectors of American industry and economy.

What the candidates have said so far

It is likely that whoever wins, we will find more continuity than change in the substance of China policy. At the same time, there have been some oblique remarks from both candidates that could portend something of future policy direction, although these are best read with a degree of caution.

On the Republican side, Trump has made critical remarks about how Taiwanese manufacturing is developing to the detriment — and at the expense — of the US, and hence the need to reshore jobs for the American people. Both Trump and his vice-presidential candidate, JD Vance, have also insisted that allies bear a larger burden for their own defence. The former president has further suggested the imposition of 60% duties on China in addition to 10% on all foreign imports. However, amid the bluster, we should keep in mind the fact that the US trade deficit with China in fact widened in the Trump years.

As vice-president serving under an incumbent who has enjoyed the world of international diplomacy, Kamala Harris has had less exposure to foreign policy than one would assume. Indeed, the primary foreign policy preoccupation for her now is to distance herself from the Israel-Hamas war that has created a humanitarian crisis of alarming proportions in Gaza, and that could pose major problems for her back home. It was ironic then, that days after President Biden announced his withdrawal from the 2024 presidential race, Vice-President Harris found herself sitting down with Benjamin Netanyahu in her first major meeting with a foreign leader since the turn of events.

... the arid reality is that for China, it matters little who wins the White House in November.

China’s realities

On China, Harris has said little beyond cursory remarks about intellectual property theft on China’s part, and the need for a “de-risking” approach. Nevertheless, it should also be noted that as vice-president, she has faithfully adhered to the contours of President Biden’s China policy. A further point to consider is that her running mate, Tim Walz, is familiar with (and to) China. He was a teacher in Guangdong in 1989 and later led student delegations to the country.

Optimists would surmise that such familiarity and experience might translate to a nuance towards China that JD Vance would not be able to provide. Yet it also bears noting that such personal encounters are nothing new in politics. After all, there is little evidence that the couple of weeks Xi Jinping spent in Iowa in 1985 had any impact on how he viewed or conducted relations with the US.

Ultimately, the arid reality is that for China, it matters little who wins the White House in November. Indeed, it is just as well that Chinese leaders are under no illusion that either of the US presidential election candidates are prepared to dial down the confrontational tone towards China. The fact is that neither will. But at least the acceptance of this will hopefully mean a more realistic view of what can or cannot be achieved in the search for robust guardrails over the next four years.