Erdoğan’s balancing act: The shifting dynamics of Turkey-China ties

Academic John Calabrese reviews the evolving nature of Turkey-China relations, noting its ups and downs under Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The relationship remains asymmetrically interdependent, but both nations are eager to inject new energy into their partnership.

Turkey’s engagement with China has intensified over the past decade, fuelled by Turkey’s participation in the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and increased economic collaboration. Forged during a time of economic and political strain in Turkey, this partnership reflects an asymmetrical interdependence and has been marked by both significant gains and notable challenges. This article explores the key phases of their complex partnership, including periods of growth, stagnation and renewed efforts at collaboration.

Influenced by domestic political and geopolitical shifts

The past decade has seen Turkey-China relations grow stronger, with the 2010 elevation of the relationship to “strategic cooperation”, paving the way for Turkey’s 2015 membership in China’s BRI.

Ankara’s BRI involvement aligned with Turkey’s pivot toward Eurasia after its EU membership bid was rejected, partly due to concerns over President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s authoritarianism, leading Turkey to seek other partners.

Not to mention that Turkey’s fragile economy — characterised by currency crises, slowing growth, rising inflation and unemployment (2018-2020), and worsened by the Covid-19 pandemic — pushed Ankara to explore alternative financing, boosting ties with China.

Under Erdoğan, the pendulum swung away from the Western democratic capitalist towards Eastern authoritarian state capitalist models, facilitating closer Sino-Turkish ties.

In many ways, the warming trend in Turkey-China relations was deeply influenced by domestic political and geopolitical shifts within Turkey. Under Erdoğan, the pendulum swung away from the Western democratic capitalist towards Eastern authoritarian state capitalist models, facilitating closer Sino-Turkish ties.

Seeking greater autonomy in foreign policy, as well as alternative avenues of financing, Ankara tempered its rhetoric on sensitive issues like the Uighurs, despite public sensitivity and a sizeable Uighur diaspora. While Erdoğan once condemned China’s actions against Uighurs as almost a genocide, Turkish authorities later confined their concerns to private discussions and even took steps to align more closely with China’s stance, such as detaining hundreds of Uighurs and designating the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM) as a terrorist organisation in 2017.

Strong economic ties with Western nations

The economic relationship between Turkey and China flourished in the years following Turkey’s inclusion in the BRI. Trade and investment from Beijing to Ankara surged, with China taking advantage of its “non-interference” policy in domestic affairs, which was particularly appealing to Turkey during its period of democratic regression following the July 2016 attempted coup. The coup had a profound impact on Turkey, leading to a consolidation of power by Erdoğan and a subsequent pivot toward stronger ties with non-Western powers, including China.

Although Turkey’s economic ties with China expanded rapidly from 2010 to 2020, it is important to consider the broader context. Turkey’s trade and investment ties with EU member states and the US were far more significant.

In July 2018, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) extended a US$3.6 billion loan package to the Turkish energy and transportation sector. The same year marked the first of a series of loans approved by the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) for energy, transportation and industrial development projects in Turkey.

The next year, China’s Central Bank transferred US$1 billion to Turkey as part of a currency swap agreement that dated back to 2012 to help support the latter’s faltering economy. Additional economic aid included multiple Chinese bailouts for Turkey’s struggling banks.

Although Turkey’s economic ties with China expanded rapidly from 2010 to 2020, it is important to consider the broader context. Turkey’s trade and investment ties with EU member states and the US were far more significant.

During that period, China did not rank among Turkey’s top export partners — Germany, the US, Iraq, the UK and Italy. Meanwhile, the most significant contributors to Turkey’s foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows were consistently the Netherlands, the US, Austria, Germany and the UK. By contrast, it is noteworthy that Chinese investments in Turkey as part of the BRI accounted for a mere 1.3% of the total, while Turkey was only the 23rd highest recipient among 80 other participants.

Turkey’s growing interest in deeper cooperation with China was also reflected in its engagement with other Eurasian entities such as BRICS+ and the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), both of which are heavily influenced by China. Turkey sought to leverage Chinese investment to bolster its economy and infrastructure, with a vision of transforming itself into a transcontinental transportation hub connecting Beijing to London.

Trade imbalance and Xinjiang issue

Yet despite the initial momentum, Turkey-China relations lagged, particularly in trade reciprocity. Although China rose to become Turkey’s third-largest trade partner, trade with China was highly imbalanced — and remains so, with 2023 imports at US$44.9 billion and exports at just US$3.3 billion.

... this imbalance is not due to energy dependence but rather to Turkey’s import of higher value-added goods from China, such as electrical machinery and high-tech products, which dominate its imports.

Unlike its trade with Russia, this imbalance is not due to energy dependence but rather to Turkey’s import of higher value-added goods from China, such as electrical machinery and high-tech products, which dominate its imports.

China’s mistreatment of the Uighur Muslim population in Xinjiang became a stumbling block to closer cooperation. This issue resurfaced in 2021 when Turkish opposition politicians openly condemned China’s actions. Beijing’s response was swift, with the Chinese ambassador responding via Twitter (X) and later being summoned by the Turkish authorities.

After Turkey criticised China’s Uighur policies, China countered by drawing attention to Kurdish regions and accusing Turkey of human rights abuses. Erdoğan subsequently attempted to repair the damage by reaffirming Turkey’s respect for China’s sovereignty while advocating for the rights of Uighur Muslims. In December 2022, during his end-of-year press conference, then Foreign Minister Mevlüt Cavuşoğlu openly criticised Beijing for restricting the Turkish ambassador’s access to Xinjiang.

The resignation of Treasury and Finance Minister Berat Albayrak, the president’s son-in-law, in 2020, a key supporter of closer ties with China, added to the challenges of maintaining a positive bilateral relationship. The next year, a deal involving a China Merchants Group-led consortium, which had agreed to buy a majority stake in the Northern Marmara Motorway-Third Bosphorus Bridge project, stalled after a failure to agree on the terms of refinancing — a prior condition for the transaction.

Turkey’s inability to fund its own railway modernisation was mirrored by China’s reluctance to invest, citing debt repayment and financial return concerns. In renewable energy, Ankara’s shift to support domestic solar and wind projects was undermined by Erdoğan’s administration, which funnelled opportunities to pro-AKP elites, sidelining Chinese firms among others.

Renewed momentum

However, by 2023, signs of a reset in Sino-Turkish relations had emerged. China’s newly reappointed foreign minister, Wang Yi, visited Ankara in July of that year, where he met with Turkish Foreign Minister Hakan Fidan and President Erdoğan. This visit marked a renewed effort to enhance mutual strategic trust and deepen cooperation. Fidan’s subsequent visit to China, which included stops in Xinjiang, further underscored Turkey’s interest in improving diplomatic ties and upgrading bilateral trade and investment relations.

Since then, there has been a flurry of diplomatic interactions. In May, as part of Turkish Energy Minister Alparslan Bayraktar’s visit to China, Turkey and China signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) for cooperation on energy transition, specifically boosting cooperation on mining, especially in critical minerals and rare earths, and building conventional and modular nuclear power plant reactors in Turkey.

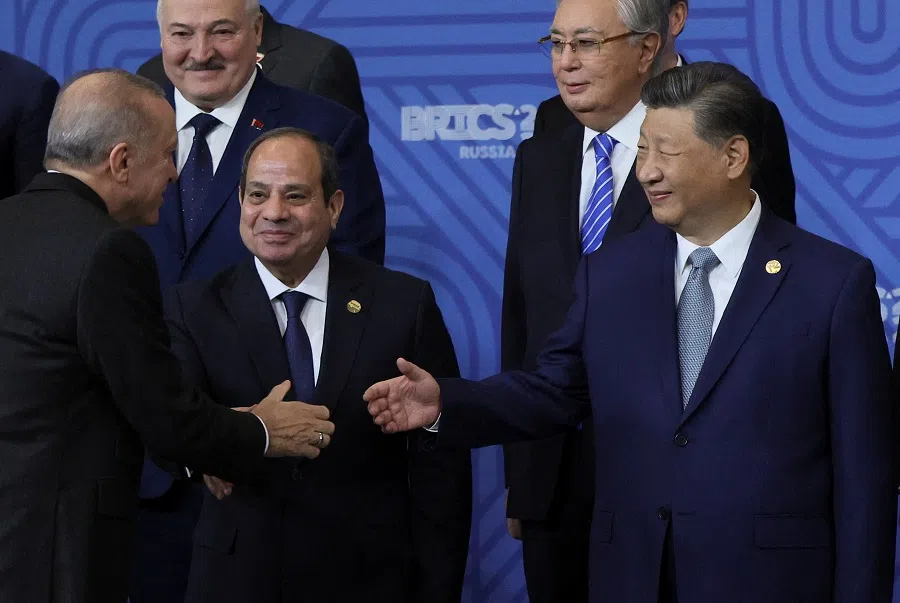

The next month, a delegation from Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) visited China and met with officials from the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), including Minister of the International Department of the CCP Liu Jianchao. In July, Presidents Erdoğan and Xi held talks on the margins of the SCO summit in Astana, Kazakhstan.

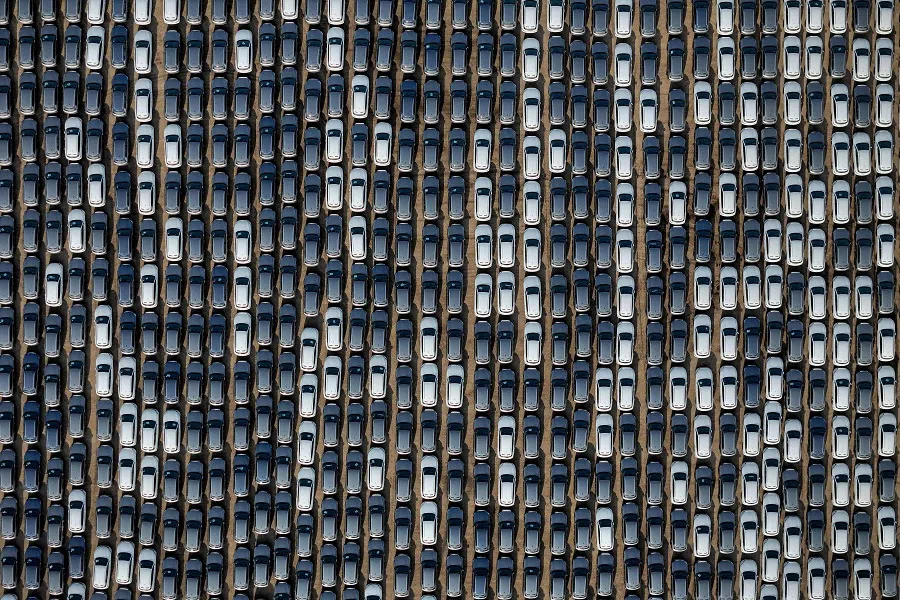

... China’s leading electric vehicle (EV) manufacturer, BYD, announcing a US$1 billion investment in Turkey to produce 150,000 electric vehicles (EVs) and hybrid vehicles annually — likely a calculated move to bypass EU tariffs and access European markets via Turkey.

During these high-level meetings, both sides expressed a commitment to enhancing economic cooperation. China pledged to encourage more Chinese companies to invest in Turkey, particularly as part of the BRI.

This was demonstrated by China’s leading electric vehicle (EV) manufacturer, BYD, announcing a US$1 billion investment in Turkey to produce 150,000 electric vehicles (EVs) and hybrid vehicles annually — likely a calculated move to bypass EU tariffs and access European markets via Turkey.

Most recently, Turkey announced its official application to join BRICS, and President Erdoğan attended the BRICS summit in Kazan in October.

Compatible visions for multipolar world

The foreign policy outlooks of Erdoğan and Xi align in their support for a multipolar world. Turkey’s “360-degree foreign policy”, which emphasises strategic independence is broadly compatible with China’s approach, particularly in Turkey’s neutral stance on the Ukraine war and the Israel-Hamas conflict.

Both leaders challenge the current global order, with Erdoğan’s critique of the UN Security Council’s structure echoing China’s positions. In addition, Erdoğan’s transactional foreign policy, which is open to engaging with various global powers, complements China’s diplomatic strategies.

However, the relationship between Turkey and China is not without its challenges. The trade imbalance remains a significant issue, with Turkish exports to China lagging far behind imports. The measures aimed at easing the imbalance were one of the top issues discussed in the Fidan-Wang meeting, the Turkish foreign minister said during the joint press conference.

Challenges creating investments of value

Though developed separately, China’s BRI and Turkey’s Middle Corridor (MC) both aim to enhance transcontinental integration. For Ankara, the MC represents the most attractive trade route between Europe and China, offering a way to lessen the Turkic states’ dependence on Russia and Iran, and improving Turkey’s connectivity with Central Asia.

Significant joint projects, such as the Ankara–Istanbul High-Speed Railway, have materialised. However, other anticipated collaborations, such as the Edirne-Kars railway have not. Despite renewed discussions in 2022, sparked by the Ukraine war, practical steps to harmonise the BRI and MC have yet to be taken. Indeed, the compatibility of the two initiatives remains unclear.

So, too, the expectation that Turkey would be a key player in the Maritime Silk Road (MSR) has fallen short, with the Greek port of Piraeus remaining central to China’s maritime strategy. Following the Chinese consortium’s 65% acquisition of the Kumport container terminal, traffic growth has been disappointing, and the integration of Turkish ports like Çandarli and Mersin have yet to be integrated into the BRI.

Chinese investments in Turkey remain dominated by low-value manufacturing and raw material extraction, despite the increasing presence of tech firms.

Amid soaring inflation and facing economic headwinds reflected in the devaluation of the Turkish currency, the lira, which hit a historic low of 33 to the dollar on 25 June, Ankara needs investment partners. In 2022 Chinese FDI in Turkey stood at US$1.7 billion, a significant rise from past FDI but still much lower than European investment in Turkey.

In 2023, China was not even listed among the ten countries with the largest investments in Turkey, surpassed by smaller countries like the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and Switzerland. A recent study has shown that Chinese investments in Turkey remain dominated by low-value manufacturing and raw material extraction, despite the increasing presence of tech firms.

Managing Western allies and overlapping interests with China

Turkey’s business sector has embraced Huawei, betting on its technology transfers and skilling initiatives to stay competitive. Huawei’s Istanbul R&D centre is its largest abroad, and over 20 Chinese digital firms are active in Turkey. Moreover, five Chinese automakers are considering setting up plants, and Turkey’s Automobile Joint Venture Group (TOGG) has partnered with China’s Farasis to manufacture EV batteries.

Yet despite the establishment of Chinese EV firms in Turkey, the EU’s foreign subsidy rules could prevent Turkey from becoming a major conduit to European markets. The EU recently slapped additional provisional tariffs of up to 38% on Chinese EVs following an investigation that concluded state subsidies meant they were unfairly undermining European rivals.

Partnerships with Chinese technology firms and a prospective Chinese investment in Turkey’s nuclear power project are two other issues likely to spark scrutiny regarding Turkey’s commitment to its Western allies. But revealingly, Turkey levied a 40% additional tariff of its own on Chinese vehicle imports from 7 July 2024, in response to concerns over market flooding and to protect its automotive industry from perceived dumping. This prompted China to file a complaint against Turkey with the World Trade Organization (WTO). Just a few days later, Turkey imposed anti-dumping duties on some steel imports from China, as well as from Russia, India and Japan.

Chinese investments in the Black Sea Region’s (BSR) infrastructure remain minimal, with sea routes and the Northern Corridor through Russia still dominating China-Europe trade. But Beijing’s recent contracts to build a major deep-sea port in Anaklia, Georgia and to expedite work on the China-Uzbekistan-Kyrgyzstan railway indicate a possible shift in strategy. Turkey’s involvement in these projects remains uncertain. Moreover, if they are implemented, they could potentially divert trade flows away from Turkey.

China-Turkey relations also have a competitive edge. Turkey strives to present itself as a supportive alternative to China and the US, particularly for Muslim-majority nations. Turkey’s 99-year lease of Sudan’s Suakin port and China’s military base in Djibouti reflect overlapping interests and rivalries, with Turkey viewing China’s growing influence in Africa as encroaching on its traditional sphere of influence. Similarly, China’s discomfort with Turkey’s engagement in Somalia highlights the geopolitical competition in the Horn of Africa.

Complex and evolving relationship

Turkey’s strategic engagement with China is also complicated by the broader geopolitical landscape. As Ankara navigates its relationships with both China and the West, it must balance its economic ambitions with the need to maintain its strategic independence and avoid becoming overly dependent on any single partner. But China and the US might tighten their trade policies against third countries to counter each other.

... Western officials are likely concerned that Turkey’s possible BRICS membership clashes with its NATO and EU ties.

Foreign Minister Fidan’s visit to China and President Erdoğan’s attendance at the 16th BRICS summit allowed Ankara to reaffirm its interest in joining the BRICS economic bloc. Turkish officials are assessing the potential benefits of membership, with improved relations with Beijing — one of BRICS’ founding members — potentially facilitating this inclusion. However, Western officials are likely concerned that Turkey’s possible BRICS membership clashes with its NATO and EU ties.

The relationship between Turkey and China is a complex and evolving one, shaped by a mix of economic interests, geopolitical considerations and historical ties. While there have been periods of significant progress, the partnership has also faced considerable challenges. The relationship remains asymmetrically interdependent, but recent developments indicate both nations are eager to inject new energy into their partnership.

As Turkey continues to pursue a multipolar foreign policy, its relationship with China will likely remain a key factor in its broader strategic calculus, with both opportunities and obstacles shaping the path ahead. Given its economic vulnerabilities and strategic position amid various conflicts — including Ukraine, the South Caucasus, the Eastern Mediterranean, Gaza and the Balkans — a balanced Turkish foreign policy that includes a robust relationship with China is more a necessity than a choice.