How the US holds the military escalation dial in Asia

In Asia, the US holds the power to decide when — and how — to act. Treaties and laws give Washington control over escalation, letting it protect allies while ensuring no one can drag America into a war it does not choose, says academic Hao Nan.

When Japanese Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi was reported on 7 November to have linked a Taiwan contingency scenario to Japan’s “survival” threshold — and later, on 16 December, to have softened her tone without fully retracting the implication — many observers treated it as a familiar flare-up in Tokyo’s domestic security debate.

But the more important audience for her words was not just Japan’s opposition benches or Beijing’s spokespersons. It was every ally and rival asking a harder question: in a region of potential fast-moving crisis and escalating tensions, what counts as a contingency for the US and its regional allies, who is covered, and when — exactly — does a crisis cross the line from diplomacy to war?

Alliances on Washington’s terms

That question matters because the most consequential shift in US strategy today may not be “strategic retrenchment” in the simplistic sense. It may be reprioritisation: a preference for narrower definitions of vital interest, a higher aversion to open-ended intervention, and a desire to keep escalation “permission” firmly in Washington’s hands.

The Trump Corollary, a resurgence of Monroe Doctrine that dominates the recently released National Security Strategy, the recent habit of “cold handling” ally talks, refusing to let rhetorical commitments harden into tripwires, and treating nuclear and European questions with studied ambiguity all point to a single pattern. While Washington is not abandoning its alliances, it is reprogramming them — away from automaticity and toward controllability.

... the decision to fight, and how hard to fight, remains a political choice — not a mechanical legal reflex.

The irony is that East Asia’s alliance texts have always been built for controllability. They were, at the very beginning, drafted by a US that wanted deterrence without blank checks, and by a US that insisted — explicitly —on preserving domestic decision rules.

That is why Asian treaties so often sound similar: an armed attack would be “dangerous”, and each side “would act” to meet the danger, but “in accordance with… constitutional processes”. The practical meaning is not “we will do nothing”. It is: the decision to fight, and how hard to fight, remains a political choice — not a mechanical legal reflex.

No one can force the US, not Japan

Compare NATO’s famous Article 5, the rhetorical gold standard. It declares an attack “shall be considered an attack against them all”, and commits each ally to assist by taking “forthwith… such action as it deems necessary, including the use of armed force”.

Even NATO preserves discretion (“as it deems necessary”), but the political meaning is intentionally blunt. By contrast, America’s East Asian architecture is a lattice: bilateral treaties with Japan, South Korea and the Philippines, plus a domestic law for Taiwan. The differences in geography and wording are exactly where “controllability” lives.

For Japan, Article V of the 1960 Japan-US Security Treaty triggers when an armed attack occurs “in the territories under the administration of Japan,” and each party “would act to meet the common danger” according to its “constitutional provisions and processes”. That is a territorial trigger, not a Taiwan guarantee.

Yet Article VI grants US forces the use of “facilities and areas in Japan” for “the security of Japan” and peace in “the Far East”. This pairing is the whole story: Washington gets basing that makes deterrence credible, while both sides keep legal and political space to calibrate responses.

If Washington is now more risk-averse, this treaty design becomes a feature, not a bug — because it discourages anyone in Tokyo from dragging the US into a war before Washington decides it wants one, which perhaps was the motivation for Takaichi, a heavyweight long associated with Japan’s right-wing, to make that controversial Taiwan contingency remark. Nevertheless, the Trump administration’s cold handling of the case proves the point.

... it does reinforce a political truth: Seoul is covered strongly at home, yet South Korea is not automatically a plug-and-play participant in every regional contingency Washington may face...

ROK, Philippines: the US decides

The US-ROK Mutual Defence Treaty is even more explicit about administrative geography. Article III covers an armed attack “in territories now under their respective administrative control”, and again says each side “would act to meet the common danger” through “constitutional processes”. A Senate understanding, enclosed in the treaty text, further tightens expectations: aid is owed in case of “external armed attack”, and US assistance is tied to territory the US recognises as under ROK administrative control.

None of this weakens deterrence on the peninsula — especially with US forces “in and about” South Korea by agreement — but it does reinforce a political truth: Seoul is covered strongly at home, yet South Korea is not automatically a plug-and-play participant in every regional contingency Washington may face, which historically referred to South Korea’s ambition to unify the peninsula and nation, and now can be linked to a potential Taiwan contingency.

The US-Philippines Mutual Defence Treaty, drafted earlier, looks similar but contains a crucial maritime twist. Article IV repeats the familiar formula — each party “would act” in line with “constitutional processes” — but Article V defines “armed attack” to include not only metropolitan and island territory, but also attacks on “armed forces, public vessels or aircraft in the Pacific”.

This is the legal hook for South China Sea scenarios. It can strengthen deterrence if Washington chooses to interpret harassment of Philippine ships as crossing the threshold. But it also gives Washington room to manage escalation: even when the definition is met, “would act” does not specify how — sanctions, escorts, deployments, strikes, or even diplomatic statements can all be argued as “action”.

... the TRA [Taiwan Relations Act] is tailor-made for a posture of: build Taiwan’s capacity, signal seriousness, but keep the final decision — and the escalation dial — inside Washington’s political system.

Taiwan: the US holds the escalation dial

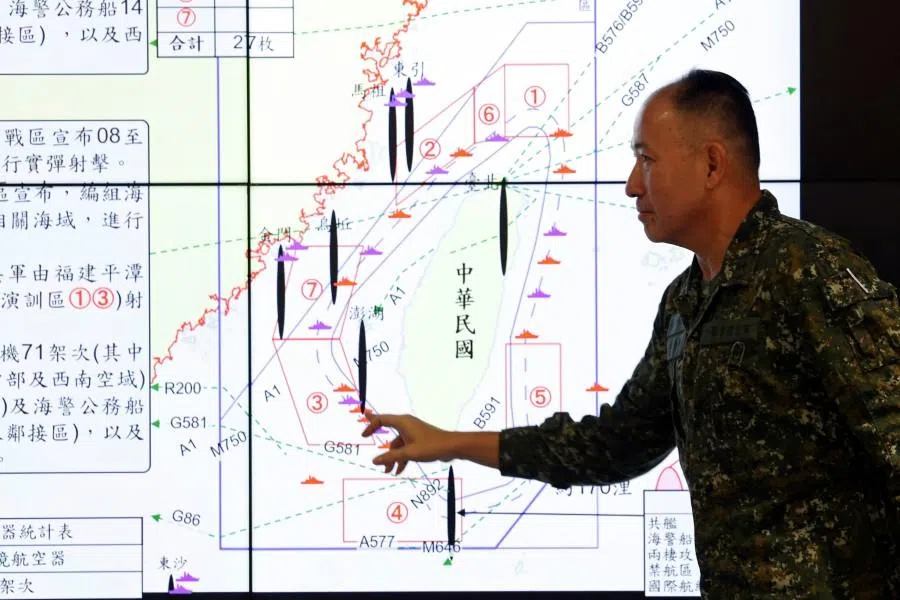

Taiwan remains the most “institutionalised ambiguity” of all because it is not protected by a mutual defence treaty. The Taiwan Relations Act (TRA), passed in 1979 following the establishment of relations between the US and the PRC, frames coercion — including “boycotts or embargoes” — as a threat to Western Pacific peace and a matter “of grave concern”, while committing the US to provide defensive arms and “maintain the capacity” to resist coercion.

But when danger arises, the Act directs that the President inform Congress, after which “the President and the Congress shall determine… appropriate action… in accordance with constitutional processes”. If the US is leaning toward strategic restraint, the TRA is tailor-made for a posture of: build Taiwan’s capacity, signal seriousness, but keep the final decision — and the escalation dial — inside Washington’s political system.

This is perhaps the new reality from 2026 onward. When Washington refuses to amplify an ally’s most forward-leaning rhetoric, it is not necessarily signalling indifference. It may be signalling discipline: don’t let partners lock in US commitments, don’t let adversaries claim the US has “pre-committed”, and don’t let crises become self-fulfilling prophecies.

The same logic appears whenever the US government avoids validating an adversary’s preferred framing — be that North Korea’s demand to be treated as a normal “nuclear state”, though President Trump and Secretary of War Pete Hegseth have orally named North Korea that way. Ambiguity, in this reading, is not the absence of strategy. It is the strategy of keeping the escalation keyhole narrow.

Why controllability matters in 2026

Looking toward 2026, three features of East Asia’s strategic environment may make a preference for “controllability” — keeping options open and escalation pathways managed — especially salient for Washington.

First, many likely contingencies involve grey-zone pressure — blockades, close-in maritime encounters, cyber operations — that sit between routine friction and a clear-cut “armed attack”. Alliance texts often offer less guidance in that space, leaving outcomes to political judgment and crisis management.

Second, the region’s expanding missile and strike capabilities shrink geography: a conflict over Taiwan could quickly involve US forces stationed in Japan, raising questions about the US-Japan treaty’s territorial trigger, while renewed fighting on the Korean peninsula could create spillover risks for both Japan and nearby US troops.

That is not betrayal; it is the predictable behaviour of a superpower trying to deter without being dragged.

Third, domestic political constraints are not unique to any one country, but they do shape credibility. Clauses referencing “constitutional processes” remind all parties that major decisions will pass through national institutions; in a crisis, that can introduce uncertainty that both allies and competitors may try to interpret — rightly or wrongly —when weighing risks.

Keeping war optional

The implication for the US’s regional allies is sobering. If Washington’s priority is risk management, then allies should expect more consultation, more burden-sharing demands and more emphasis on capabilities that prevent faits accomplis — air and missile defence, anti-ship fires, resilient basing, stockpiles, rapid repair, and coast-guard capacity.

They should also expect Washington to use treaty “wiggle room” to prevent entrapment: to say “yes” to alliance goals while reserving the right to say “not that way, not that fast”. That is not betrayal; it is the predictable behaviour of a superpower trying to deter without being dragged.

Takaichi’s episode is a miniature of the larger moment. Her hint — Taiwan contingency as Japan's “survival” logic — pushed toward clarity. The subsequent softening pushed back toward ambiguity. Between those poles sits the reality of America’s East Asian commitments: strong enough to matter, flexible enough to manage, and increasingly interpreted through a Washington that wants to keep war optional — even while keeping deterrence credible.

Treaty words like “would act”, the repeated insistence on “constitutional processes”, the Philippines’ “public vessels” clause, and the TRA’s “grave concern” framework were always designed to balance commitment with control. The question for 2026 is whether allies and adversaries read that balance as steady deterrence — or as an invitation to probe. Managing that perception, more than any single speech, is the real fight.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)