Hun Manet leads Cambodia out of Vietnam’s shadow

Cambodia’s withdrawal from the 25-year-old Cambodia-Laos-Vietnam Development Triangle Area (CLV-DTA) framework signals a more assertive Cambodian foreign policy and portends a sharp decline in relations with Vietnam.

In an astounding turn of events, Cambodia has withdrawn from the Cambodia-Laos-Vietnam Development Triangle Area (CLV-DTA). The 25-year-old sub-regional framework had been in place to strengthen socioeconomic, migration and defence ties between the three neighbours through interprovincial cooperation. The CLV-DTA, encompassing 13 provinces (four in Cambodia, four in Laos and five in Vietnam), was motivated by a shared desire to enable economic exchanges across the three countries’ borders.

While acknowledging that the CLV-DTA “has been immensely beneficial” for countries involved, the Cambodian Ministry of Foreign Affairs officially informed Vietnam in a letter that “the cooperation mandate has reached its objectives”.

In August, Vietnamese spokesperson Pham Thu Hang underlined the strategic importance of the economic pact, highlighting that it helped “promote economic, trade and people-to-people exchanges between the three countries”. Pham also pledged to work closely with Cambodia and Laos to ensure the smooth organisation of the CLV-DTA Summit, which was scheduled to be held in Cambodia later this year.

A wedge between Cambodia and Vietnam

Cambodia’s bewildering retreat not only shocked Vietnamese leaders but also heightened the intricacy of the bilateral relationship. The gloomy future of the trilateral deal comes at a worrying time since opponents and extremists have stepped up their efforts to drive a wedge between the Cambodian ruling party and the Vietnamese government by blaming the pact with Vietnam for causing the loss of Cambodian sovereignty.

The two-decade-old agreement has been a flashpoint for the long-simmering flame of nationalism and anti-Vietnam sentiment in Cambodia. Opponents claimed that the CLV-DTA caused “deforestation, land conflicts and [is] a threat to Cambodia’s sovereignty”, and accused the ruling government of ceding four northeastern provinces to its bigger eastern neighbour. The Hun administration has faced calls to back out of the deal because Phnom Penh could lose natural resources and territory to Vietnam.

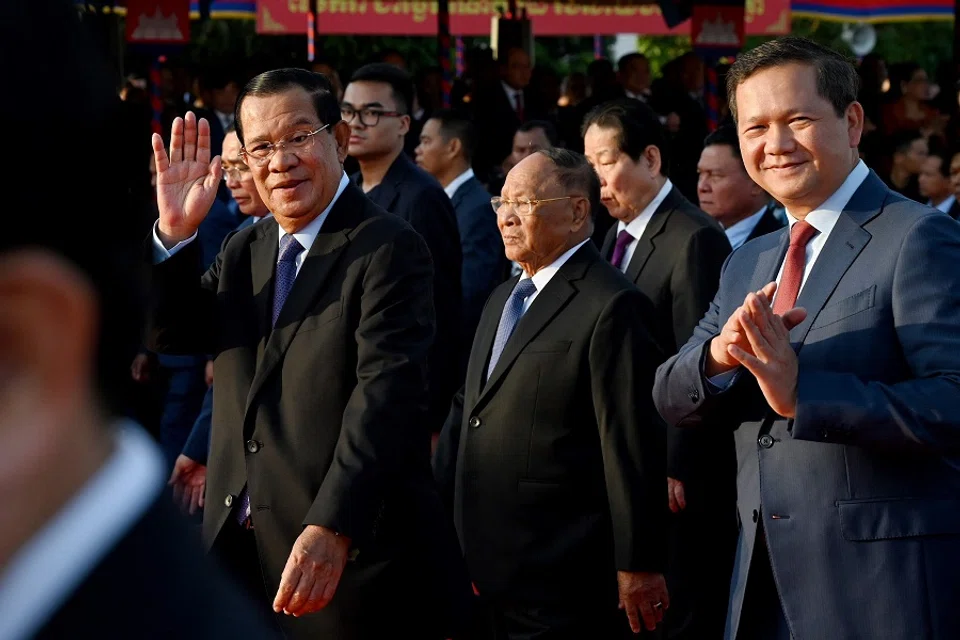

In his Facebook post, Hun Sen, president of the Senate and the ruling Cambodian People’s Party, said this decision was aimed at “withdrawing weapons out of the hands of extremists”, who exploited the agreement to “slander the government and confuse the public”. Before the CLV-DTA withdrawal, the Cambodian government warded off dissent by arresting political opponents and activists.

Here, the departure could help the government quell nationalist criticism of the ruling party and bolster its legitimacy, indicating the Hun administration’s priority of internal political factors, particularly domestic stability, above regional economic engagement.

Hun administration prioritising domestic stablity

Phnom Penh has been intent on charting its own course out of Vietnam’s shadow.

Hun Sen asserted that the deal pullout could deter extremists from targeting the Cambodian government. Yet his reasoning seemed more like a populist gambit than a prudent and balanced attempt to address dissidents’ concerns. While Cambodia’s daring move may bring together diverse factions within society and silence critics for the time being, it is unclear whether this nationalism-driven approach can shelter the Hun regime from malign attempts to discredit its reputation.

Cambodia’s decision also leaves unanswered the question of how the Hun administration could fulfil its commitments with neighbouring countries. Ironically, Hun Sen’s 1999 pitch for a regional mechanism to cultivate multidimensional ties with Vietnam and Laos inspired what would later become the CLV-DTA.

Now Hun Manet, Hun Sen’s son and the Cambodian prime minister, who in August underscored that the deal “did not contain any provision for land swaps”, has terminated the framework recognised by Cambodian academics as “a bedrock” for enhancing trilateral ties on trade, connectivity and infrastructure development.

The effectiveness of the CLV-DTA, which is relatively weak, could be the reason why Cambodia is not so enamoured with this mechanism. Here, the departure could help the government quell nationalist criticism of the ruling party and bolster its legitimacy, indicating the Hun administration’s priority of internal political factors, particularly domestic stability, above regional economic engagement.

While superpower rivalry influences the international disposition of smaller states like Cambodia, there is significant room to manoeuvre and forge ties with like-minded partners thanks to minilateral institutions that inspire regional collaboration. By focusing on the practical benefits of the CLV-DTA — such as allowing citizens to freely travel through border provinces specified in the agreement and boosting Cambodia’s economic growth and trade value with Vietnam — the two neighbouring countries could still harmonise their interests despite the CLV-DTA’s effective dissolution and curb attempts to sow distrust among them.

Since Hun Manet does not share his father’s personal ties with Vietnamese leaders, he has greater leeway to shape Cambodia’s foreign policy and enhance his political standing.

Bolstering its strategic autonomy vis-à-vis Vietnam

Yet this contentious move undermines Cambodian leaders’ vow to expand economic, defence and security ties to foster “peace, stability and development in the Cambodia-Vietnam border provinces”. Cambodia’s withdrawal from CLV-DTA — and its unlikely re-entry — constrain the support it could get from Vietnam to secure its borders from illegal activities such as drug, small arms and human trafficking. Vietnam’s cooperation is important, considering the Cambodian government’s notoriously “lax approach to immigration” and the “limited resources” available to Phnom Penh for monitoring overland crossings.

Cambodia’s withdrawal is contentious for another reason: ties with Vietnam have been on the rocks recently due to its resolve to build the China-funded Funan Techo Canal while refusing to negotiate with Hanoi over ecological and security concerns. As a Vietnamese proverb goes, “taking advantage of the wind to pick bamboo shoots”, this calculated move is perhaps an indication of Cambodia’s efforts to bolster its strategic autonomy vis-à-vis Vietnam. Since Hun Manet does not share his father’s personal ties with Vietnamese leaders, he has greater leeway to shape Cambodia’s foreign policy and enhance his political standing.

In a nutshell, Phnom Penh has been intent on charting its own course out of Vietnam’s shadow. The government’s letter conveyed to Vietnam makes it clear: “At this point, we believe that each country is fully capable of continuing and ensuring the independent development of its respective nation.” The undercurrents of discontent of this “brotherly friendship” now come to the fore with a more confident and assertive Cambodia.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.