Marcos's visit to Vietnam: When Manila's pivot meets Hanoi's pragmatism

Vietnam and the Philippines have agreed to strengthen maritime cooperation in the South China Sea. Digging deeper, however, the two countries are taking distinct approaches in countering the Chinese coercion in the maritime area.

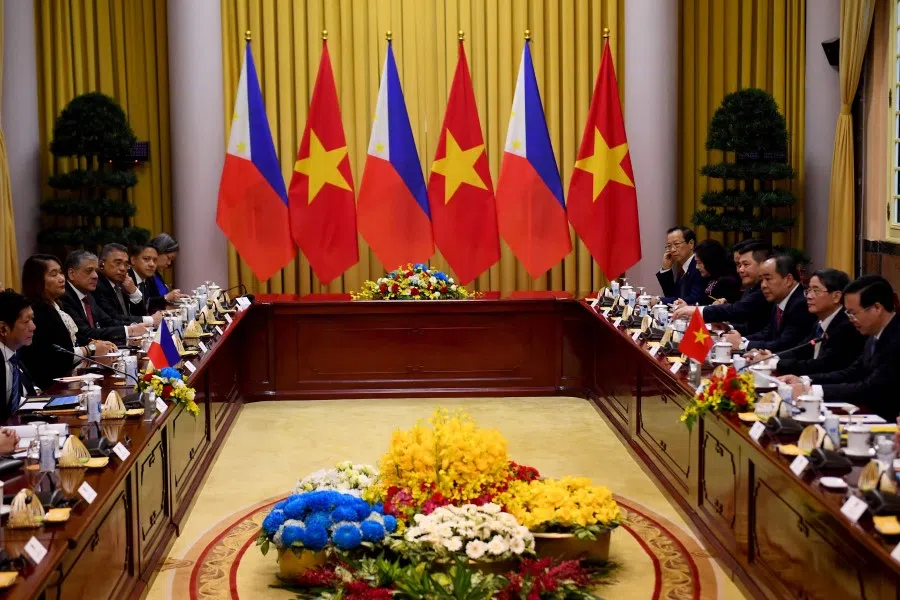

Philippine President Marcos Jr's recent state visit to Hanoi marks his first official trip in 2024. While the agenda covered a broad spectrum of bilateral cooperation, including agriculture, culture, investment and trade, the geopolitical dynamics underlying his visit are equally significant.

As the Philippines is now the frontline state in countering Chinese coercion in the South China Sea (SCS), strengthening maritime cooperation with Hanoi was Manila's key priority during Marcos's visit, as emphasised by the president himself.

An important outcome of the visit was the signing of two memorandums of understanding (MOUs) on incident prevention in the SCS and on coast guard cooperation. Both sides agreed to resume their joint commission on maritime and ocean cooperation at the vice-ministerial level.

Of particular significance was Manila's expressed willingness to explore developing a joint submission with Vietnam on the extended continental shelf before the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS).

Vietnam had previously submitted a joint submission with Malaysia. Another joint submission with the Philippines would be a concrete step by Southeast Asian claimant states in upholding the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), thereby rejecting China's nine-dash line as unlawful.

... they should not be overinterpreted as signifying a unified Manila-Hanoi stance in pushing back against China's actions in the SCS.

Rebuilding trust between Vietnam and the Philippines

These agreements serve to rebuild trust and mitigate potential incidents between Vietnam and the Philippines, particularly in light of recent tensions over their maritime disputes.

Last year, Vietnam publicly criticised Manila for "violating its sovereign rights" in the Spratlys. There was also an outcry in some Philippine news outlets against Vietnamese militarisation in the SCS, which exposed the vulnerability of the Manila-Hanoi nexus to a third party's wedge strategy (read: by China), including a disinformation campaign in social media aimed at diverting attention away from China's harassment of Philippine vessels.

While the outcomes from Marcos's visit are instrumental in solidifying mutual trust and maritime cooperation between Vietnam and the Philippines, they should not be overinterpreted as signifying a unified Manila-Hanoi stance in pushing back against China's actions in the SCS.

Since coming to office, Marcos has made an about-turn from his predecessor in foreign policy, particularly on the SCS. Manila has pivoted back towards strengthening its security alliance with the US, pushing back against Chinese encroachments in the maritime area, and even contemplating a more proactive stance on potential contingencies over the Taiwan Strait.

Notably, Manila has also sought to bolster defence-security cooperation with key US allies, including Japan, Australia and Canada, reflecting a trend of forging minilateral coalitions within the US alliance network to counter China in the SCS.

While Washington may not always be at the forefront, it has been playing a subtle yet influential role in pushing for these coalitions. Marcos's visit to Vietnam appears to align with this strategy, which seeks to forge a more tightened Manila-Hanoi nexus on the SCS issue in the face of a silent and divided ASEAN.

Hanoi has been careful to avoid provoking Beijing, with which it agreed to build a "community of shared future" during President Xi Jinping's visit in December last year.

Vietnam maintaining a more cautious stance

Yet Manila's enthusiastic overtures are not met with equal fervour by Hanoi. In contrast to Manila's emphasis on the SCS issue during Marcos's visit, Hanoi appears far more reserved.

The Malacañang Palace's press releases regarding the visit prominently featured Marcos's remarks on the SCS and his criticism of China's aggressive actions against Philippine vessels. In contrast, Vietnamese media coverage of the event provided a broader representation of the bilateral ties; references to the SCS and maritime cooperation with the Philippines were made in passing rather than being the central focus. This indicates Hanoi's reluctance to amplify these aspects during Marcos's visit.

Unlike Vietnam, the Philippines is shifting away from the ASEAN-led approach to the SCS, which primarily revolves around negotiations with China on a code of conduct (COC). Instead, Manila is leaning towards a deterrence-based strategy, relying on its alliance with the US and enhancing minilateral security cooperation within a network of like-minded states. The Philippines is even advocating for a minilateral approach within ASEAN by proposing a separate COC among Southeast Asian claimant states.

In contrast, Vietnam still maintains a cautious stance, emphasising the need to properly implement the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) and develop an "effective and substantive COC", despite the fact that both processes have proven ineffective in curbing China's coercion in the SCS. Hanoi has been careful to avoid provoking Beijing, with which it agreed to build a "community of shared future" during President Xi Jinping's visit in December last year.

Inherent volatility in the Philippines' foreign policy

Unlike the assertive stance taken in the early 2010s, Vietnam's handling of the SCS issue has become more subtle and low-key in recent years as it has chosen to prioritise stable and friendly ties with China and focus on other productive aspects of the relationship.

The divergence between the Philippines and Vietnam's approaches to the SCS underscores the different pathways of their foreign policy in navigating the US-China rivalry. Hanoi has been more pragmatic in its "bamboo diplomacy" to cultivate positive relations with both Washington and Beijing, whereas Manila has chosen a more overt alignment with the US.

The Manila-Hanoi nexus in the SCS therefore remains tenuous given the need to reconcile the former's adventurism and the latter's pragmatism.

Hanoi may also quietly question the sustainability of Manila's pivot, given the latter's historical pattern of changing foreign policy directions with each new presidential administration. This concern becomes particularly relevant in light of the current political upheaval in Manila with the impending collapse of the Duterte-Marcos alliance.

Vice President Sara Duterte, the daughter of former President Rodrigo Duterte, was leading as the 2028 presidential election frontrunner in a recent poll. During his tenure, the former president downplayed the SCS dispute and fostered closer ties with China.

The inherent volatility of the Philippines' foreign policy, and thus its fluctuating and sometimes adventurous approach to the SCS, stands in stark contrast with Vietnam's risk-averse approach, which is meticulously calibrated and highly sensitive to China's reaction.

The Manila-Hanoi nexus in the SCS therefore remains tenuous given the need to reconcile the former's adventurism and the latter's pragmatism.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute's blogsite.