Post-Assad Syria: A test for China’s Middle East ambitions

With the fall of the Assad regime, Syria’s alliances have been disrupted and its internal rivalries are laid bare. In this situation, says US academic John Calabrese, China might collaborate with Gulf Arab countries to shape Syria’s reconstruction and maintain its continued influence. However, this could be a long and challenging process.

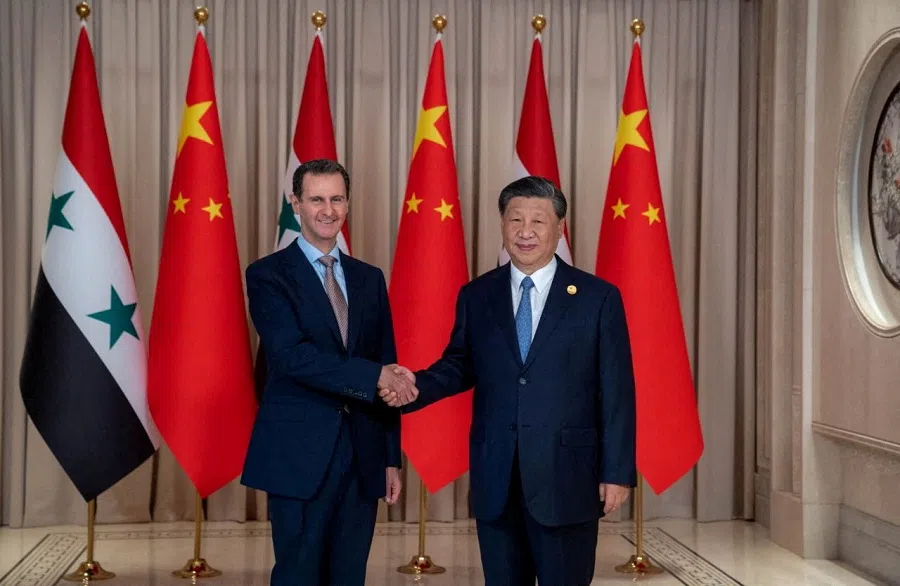

In a stunning turn of events, Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s regime, sustained for over five decades with the backing of powerful allies like Russia, Iran and Hezbollah, crumbled in under two weeks. What are the immediate repercussions in the Middle East, and what might this mean for China’s role in Syria and the broader region?

Fluid situation, new alignments

The regime’s downfall came swiftly when an Islamist rebel coalition led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) took control of key cities like Aleppo, Hama and Homs, and began advancing towards Damascus. With a weakened, underpaid and demoralised military, Assad’s forces — a hollow shell after 14 years of conflict — barely resisted. The regime’s international backers, Russia and Iran, also withdrew support, further exposing the regime’s vulnerabilities. The rebels’ quick success was influenced by external factors, including Israeli airstrikes against Hezbollah and the unraveling of Assad’s alliances with Iran and Russia.

This development opens the door for a realignment of relationships, notably between Iran, Russia, Turkey and Israel.

The collapse of Assad’s regime represents a significant shift in the Middle East’s geopolitical balance. The region’s longstanding power structures, particularly the alliances formed under Assad’s leadership, have fractured. This development opens the door for a realignment of relationships, notably between Iran, Russia, Turkey and Israel. The withdrawal of Russian and Iranian support has left a vacuum, with Moscow facing a loss of its only major ally in the region, while Tehran’s logistical and military operations through Syria are now under significant strain.

The HTS-led rebellion marks the culmination of the Syrian civil war, leading to a major shift in the region’s power structure. While Syrians celebrated the regime’s collapse, the country’s future remains uncertain, with competing factions and the remnants of ISIS still posing significant challenges. The international community, including Western and Gulf states, faces the task of helping Syria transition to stable governance and rebuild its war-torn infrastructure.

Reports from Kremlin sources indicate that Assad fled to Moscow with his family and was granted asylum on humanitarian grounds. Meanwhile, Syria’s situation remains fluid. Rebel and Kurdish-led forces now control most of the country, and a transition is underway involving members of Assad’s government. However, the future leadership of Syria remains unclear, and questions persist about the role of foreign forces, including those from Russia and Iran.

Preventing chaos in post-Assad Syria

The ongoing conflict highlights the complex web of alliances and rivalries in Syria. Over the weekend, Turkey’s military clashed with US-backed Kurdish forces in northern Syria, reportedly killing over 20 members of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Turkey considers the People’s Protection Units (YPG), the Kurdish militia leading the SDF, a terrorist group, which complicates relations between NATO allies. The clashes led to a phone call between US Defence Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III and Turkish Defence Minister Yasar Guler, during which both reportedly agreed on the need for coordination to prevent further escalation and minimise risks to US forces and allies.

In response to the instability, US President Joe Biden called Assad’s fall a “fundamental act of justice” after years of brutal repression but acknowledged the risks and uncertainty it created. Biden confirmed that US troops would remain in eastern Syria to maintain stability and ensure the fight against ISIS continues. Approximately 900 US troops have been deployed there as part of an anti-ISIS coalition, and the US military struck ISIS targets in Syria’s desert region, a move facilitated by the partial withdrawal of Russian forces.

... regional and Western stakeholders — caught off guard by the rapid developments — are unified in their apprehension that the HTS-led rebel coalition might establish a hardline Islamist government or fail to curb extremist forces.

Additionally, Israel has taken steps to secure its borders, sending forces into the buffer zone beyond the Golan Heights to prevent Islamist groups from seizing the region, after reports indicated that Syrian troops had abandoned their positions, leaving weapons behind. This marks Israel’s first overt military action in Syrian territory since the 1974 ceasefire agreement with Syria.

The collapse of the Assad regime has struck a critical blow to Iran’s “axis of resistance”. Syria, once a pivotal transit hub for arms and fighters moving between Iran, Syria and Lebanon, now poses significant logistical challenges for Tehran. According to the Mehr News Agency, Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi acknowledged on state television that the resistance front has faced over a year of challenges — though his remarks fail to fully convey the extent of the setbacks. Assad’s ouster comes on the heels of Hezbollah’s devastating losses and the elimination of key leaders of Hamas and Hezbollah by Israel.

Araghchi also reported holding discussions with representatives from eight regional countries, all emphasising the need to prevent Syria’s disintegration and block the resurgence of ISIS. Indeed, at this nascent stage of post-Assad Syria, regional and Western stakeholders — caught off guard by the rapid developments — are unified in their apprehension that the HTS-led rebel coalition might establish a hardline Islamist government or fail to curb extremist forces. Statements from Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey and the UAE emphasise the importance of preserving Syria’s unity and preventing non-state actors from exploiting the political vacuum.

Filling the power vacuum with an inclusive and swift political transition will be a daunting task. In his first address after seizing Damascus, Ahmad al-Sharaa, also known as al-Jolani, leader of HTS, declared the dawn of a new era for the region, calling Syria “a beacon for the Islamic nation” — eerily reminiscent of the Taliban’s 1990s ascent to power in Afghanistan. Meanwhile, Hadi al-Bahra, president of the Syrian National Coalition, has proposed an 18-month transition plan, but the coalition wields little influence on the ground, where armed factions hold sway. Most recently, Mohammed al-Bashir, erstwhile head of the HTS-led Syrian Salvation Government (SSG) in the northwest area of Idlib, has been named the transitional prime minister until March 2025.

China’s approach and potential involvement

The sudden ouster of Bashar al-Assad has prompted a measured and cautious response from China, reflecting its emphasis on stability, sovereignty and non-intervention in international affairs. China’s approach to this development underscores its dual priorities of safeguarding its interests in Syria and maintaining its broader foreign policy principles.

Beijing has expressed deep concern over the situation, emphasising the need for a swift political resolution that respects Syria’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. The Chinese foreign ministry has called on all parties to prioritise the fundamental interests of the Syrian people and to work towards a long-term political settlement.

China’s involvement in Syria could align with broader regional efforts to stabilise the Middle East and counterbalance the influence of Iran and Russia.

In this volatile context, China’s strategic interests in Syria are twofold: securing its investments in the region and preserving its influence over key initiatives, such as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). While Syria’s participation in the BRI was meant to enhance infrastructure connectivity and economic ties, the political instability and fragmentation that followed Assad’s fall have put these projects on hold. China now faces the challenge of balancing its desire to maintain economic ties with the country while adapting to a rapidly shifting political landscape.

China’s immediate focus has been on ensuring the safety of its citizens and organisations in Syria. The Chinese embassy in Damascus remains operational, assisting Chinese nationals with departure arrangements and issuing safety guidelines. Furthermore, Beijing has called on all relevant parties within Syria to guarantee the security of Chinese personnel and infrastructure, signalling its concern for maintaining its presence and protecting its investments in the country.

Moreover, China’s growing partnerships with Gulf Arab states, including its investments in energy, trade and infrastructure, could influence its position in Syria’s post-Assad reconstruction. If China can work alongside these Gulf states, whose interests align with stability and reconstruction, it could gain access to new markets and support for rebuilding efforts. In this respect, China’s involvement in Syria could align with broader regional efforts to stabilise the Middle East and counterbalance the influence of Iran and Russia.

If a pragmatic Syrian leadership emerges, willing to overlook Beijing’s past support for the Assad regime and lift sanctions, China could eventually engage in Syria’s reconstruction and access a significant export market. However, China’s own economic slowdown may temper its commitments. With the diminished influence of Iran and Russia, China lacks a strong economic partner to stabilise the Syrian economy or facilitate rebuilding. In response, Beijing may seek to collaborate with Gulf Arab countries to shape Syria’s reconstruction, ensuring continued engagement.

Beijing’s future role in Syria will depend largely on how the political landscape unfolds and whether a new leadership emerges with pragmatic policies conducive to Chinese investment.

Critical turning point for Middle East

The toppling of Assad’s regime marks a critical turning point not only for Syria but for the entire Middle East. The rapid collapse of the regime has created a power vacuum that threatens to destabilise the region even further, with competing factions vying for control and the risk of extremist groups regaining influence. This shift challenges existing alliances, particularly the role of Russia and Iran, whose influence in Syria is now diminished. For China, the developments in Syria present both challenges and opportunities. While Beijing’s commitment to non-intervention and sovereignty remains unwavering, the growing instability puts its economic interests in the region at risk.

China’s strategic foothold in Syria — once poised to expand through its Belt and Road Initiative — faces significant setbacks because of Assad’s fall. Beijing’s future role in Syria will depend largely on how the political landscape unfolds and whether a new leadership emerges with pragmatic policies conducive to Chinese investment. However, the political fragmentation and the presence of competing international and regional powers complicate China’s ability to secure its interests in the short term.

Moreover, Syria’s disintegration could have far-reaching implications for China’s broader Middle East strategy. As Beijing deepens its ties with Gulf states and seeks to play a more prominent role in regional reconstruction, it will have to navigate a complex web of interests and align itself with stakeholders that prioritise stability and reconstruction.

China’s involvement in Syria is now intricately linked to the success of broader regional stabilisation efforts, and its ability to adapt to the evolving geopolitical dynamics will define its future role in the Middle East. Ultimately, while the fall of Assad has upended Syria’s political order, it has also set the stage for a new chapter in the Middle East’s evolving power structures — one in which China’s influence will be tested as it balances its long-term economic interests with the realities of a fragmented and volatile region.

![[Big read] Paying for pleasure: Chinese women indulge in handsome male hosts](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/c2cf352c4d2ed7e9531e3525a2bd965a52dc4e85ccc026bc16515baab02389ab)

![[Big read] How UOB’s Wee Ee Cheong masters the long game](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/1da0b19a41e4358790304b9f3e83f9596de84096a490ca05b36f58134ae9e8f1)