Damascus falls: China’s Middle East dilemma deepens

With the fall of Damascus and greater instability in the Middle East, China is likely to tread carefully and be even more cautious about overcommitment in the region, says academic Alessandro Arduino.

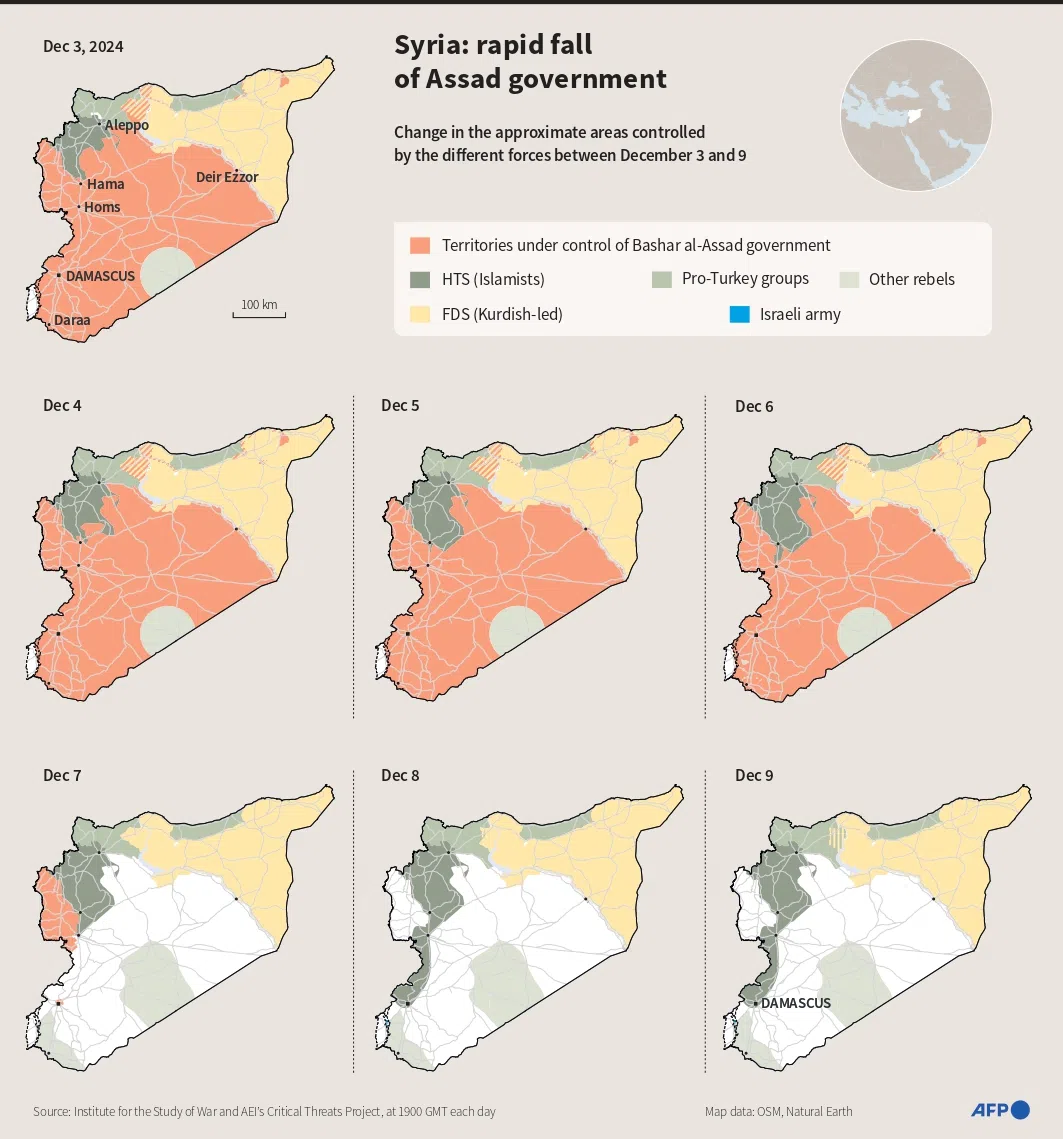

The fall of Damascus has thrown China and the global community into a state of surprise and uncertainty. The speed of events caught everyone off guard. However, it was not the lightning-fast rebels’ offensive alone, seizing the capital in ten days, that exposed the hollow nature of Assad’s security apparatus. Instead, it was 13 years of brutality and corruption that ultimately led to this moment.

Power dynamics shifting in the Middle East

While celebrations of Bashar al-Assad’s ousting — amid reports from Russian state television that he arrived in Moscow on Sunday — are erupting worldwide, the real challenge lies in managing the aftermath. The power vacuum left behind raises critical questions: will Syria devolve into a terrorist haven, a failed state like post-Gaddafi Libya, or even a narco-state fuelled by the production and trafficking of the banned substance Captagon?

These setbacks may push Tehran’s leadership toward doubling down on its nuclear ambitions.

Already on 7 Oct 2023, an attack on Israel unleashed a wave of violent retaliation that changed the region’s power dynamics. The fall of Damascus is set to ignite a new profound reshuffle of power balance in the region and beyond. The Middle East has shifted once again.

Iran’s proxy strategy of the “Shia crescent”, with Syria as the funnel for the Iranian arms used by militant groups to attack Israel is now in disarray. These setbacks may push Tehran’s leadership toward doubling down on its nuclear ambitions. At the same time, Russia’s naval and air presence in the region is severely undermined.

The collapse tarnishes the perception of Russian mercenaries and military forces as steadfast protectors of their allies, while also severing vital logistical links to Libya and undermining its broader regional ambitions. For Russia, Syria served as a strategic launchpad for projecting power and a crucial asset in its global power ambitions.

Israel did not waste time, announcing that it had entered the demilitarised buffer zone in the Golan Heights, bordering Syrian-controlled territory to prevent violent spillovers, and probably deploying troops into Syrian territory. To prevent ISIS from exploiting the situation to reestablish itself, the US launched numerous airstrikes, including some with the use of B52 bombers, and pledged continuity in the support of the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces in northeastern Syria.

Turkey now emerges as the new kingmaker in the region, wielding significant influence over the unfolding dynamics thanks to the support of the leading rebel forces and a military presence inside Syrian territory along the shared border.

Iraq also remains a key concern for Beijing as negative ripple effects from Damascus may reach Baghdad and Erbil.

Fears of terrorist organisations and spillover effects on Iraq

China’s steps however remain uncertain, and it will probably keep treading cautiously in a volatile Middle East.

While Syria holds peripheral interest for China compared to other areas in the Middle East, the uncertainty stemming from Damascus’s collapse will keep Zhongnanhai on high alert. The deepening chaos in the region raises the spectre of terrorist organisations exploiting the situation, potentially leading to a resurgence of terrorism in the Middle East. More so given that the leading rebel group, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), is a former al-Qaeda affiliate and designated as a terrorist organisation by both the US and the UN.

The fallout from the Assad regime’s downfall poses a particular challenge for China, whose primary foreign policy tools are economic and financial rather than security-focused. These developments may force China to deepen its relationship with Turkey.

At the same time, China appears to have learned its lesson from the fall of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya, which underscored the risks of over-investing in unstable regions. Despite Damascus’s early call for massive investments, Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) kept a low profile.

Iraq also remains a key concern for Beijing as negative ripple effects from Damascus may reach Baghdad and Erbil. Geng Shuang, China’s deputy permanent representative to the United Nations (UN), recently highlighted Beijing’s worries about the potential spillover effects of Syria’s instability on Iraq.

Speaking at a UN Security Council briefing on 6 December, he emphasised China’s support for Iraq’s central government and the Kurdistan Regional Government in resolving outstanding issues through dialogue and sustainable solutions. More than Syria, Iraq is central to China’s energy security strategy, with Chinese investments in southern Iraq, particularly in Basra, playing a vital role in securing oil and gas supplies.

Another significant anxiety for Beijing is the potential for Uighur extremists to join jihadist groups in Syria, with the risk of future militant training spilling over into Central Asia.

China will tread carefully amid security concerns

Another significant anxiety for Beijing is the potential for Uighur extremists to join jihadist groups in Syria, with the risk of future militant training spilling over into Central Asia. This worst-case scenario continues to shape China’s cautious approach to the region.

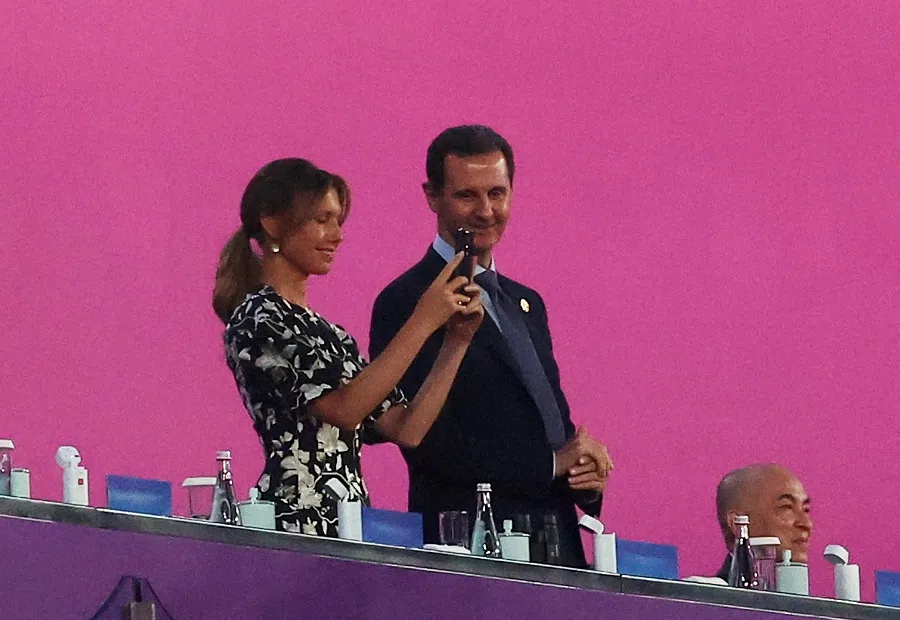

China has long been wary of over-commitment. Despite hopeful expectations from figures like Hassan Nasrallah in Lebanon and Bashar al-Assad in Syria, Beijing has consistently taken a wait-and-see approach. Even in September 2023, when Assad was welcomed back into the Arab League and met President Xi Jinping in Hangzhou during the 19th Asian Games, Xi’s pledge to back Syria’s reconstruction, counterterrorism efforts and political settlement under the principle of “Syrian-led, Syrian-owned” reinforced Beijing’s longstanding non-interference policy.

Since the 2018 reconstruction and trade summits, Damascus’s hopes for large-scale Chinese investments have been high. At the time, Chinese SOEs pledged US$2 billion in investments, and bilateral trade reached US$1.3 billion in 2019, according to the Chinese Ministry of Commerce. However, despite China’s provision of medical equipment during the Covid-19 pandemic, its economic engagement has not been as expected by its Syrian counterparts.

China’s broader Middle East diplomacy, such as brokering a detente between Saudi Arabia and Iran and engaging in reconstruction efforts, reflects its strategy of linking economic development with security stabilisation. This positions China as an alternative to Western powers in the global south. Yet the eruption of violence in the region following 7 October 2023, including the conflict in Gaza and the collapse of Damascus, has disrupted Beijing’s plans. It underscores the challenges of broadening its traditional trade and investment-focused role in the region while compelling China to tread cautiously in the Middle East quagmire.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)