Southeast Asian perceptions of China: Beijing’s growing power is recognised, but feared

Data from a multi-year trend analysis of Southeast Asian perceptions of China suggest that the region remains apprehensive about China’s growing power and influence. Yet in the face of greater uncertainty over the future of the US’s leadership role in the region, the preference has been to try to keep the peace with China.

The ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute has been publishing its State of Southeast Asia (SSEA) survey report every year since 2019. The survey seeks to capture perceptions of experts and opinion makers across Southeast Asia on strategic matters.

It employs a random purposive sampling of over 100 respondents in each of the ten ASEAN member states — constituting a sample size of around 1,000 respondents ASEAN-wide. A 10% weighting average is then applied to each country’s responses to calculate the regional average to ensure that each country is equally represented, similar to ASEAN’s consensus decision-making process.

This article focuses on the data trends pertaining to regional attitudes towards China. Serving as an update on a similar report published last year on the region’s attitudes towards the US, this analysis crystallises some key takeaways on the region’s perceptions of China’s power and influence vis-à-vis the US, and the messages the region is telegraphing to China regarding concerns over the future trajectory of intensifying US-China strategic rivalry.

Across Southeast Asia, there is a heightened sense of uncertainty over the future trajectory of US leadership amidst deepening polarisation in its domestic politics and the US presidential elections in November this year.

If forced to choose

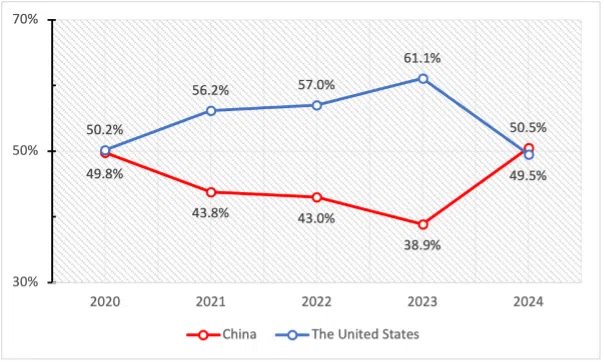

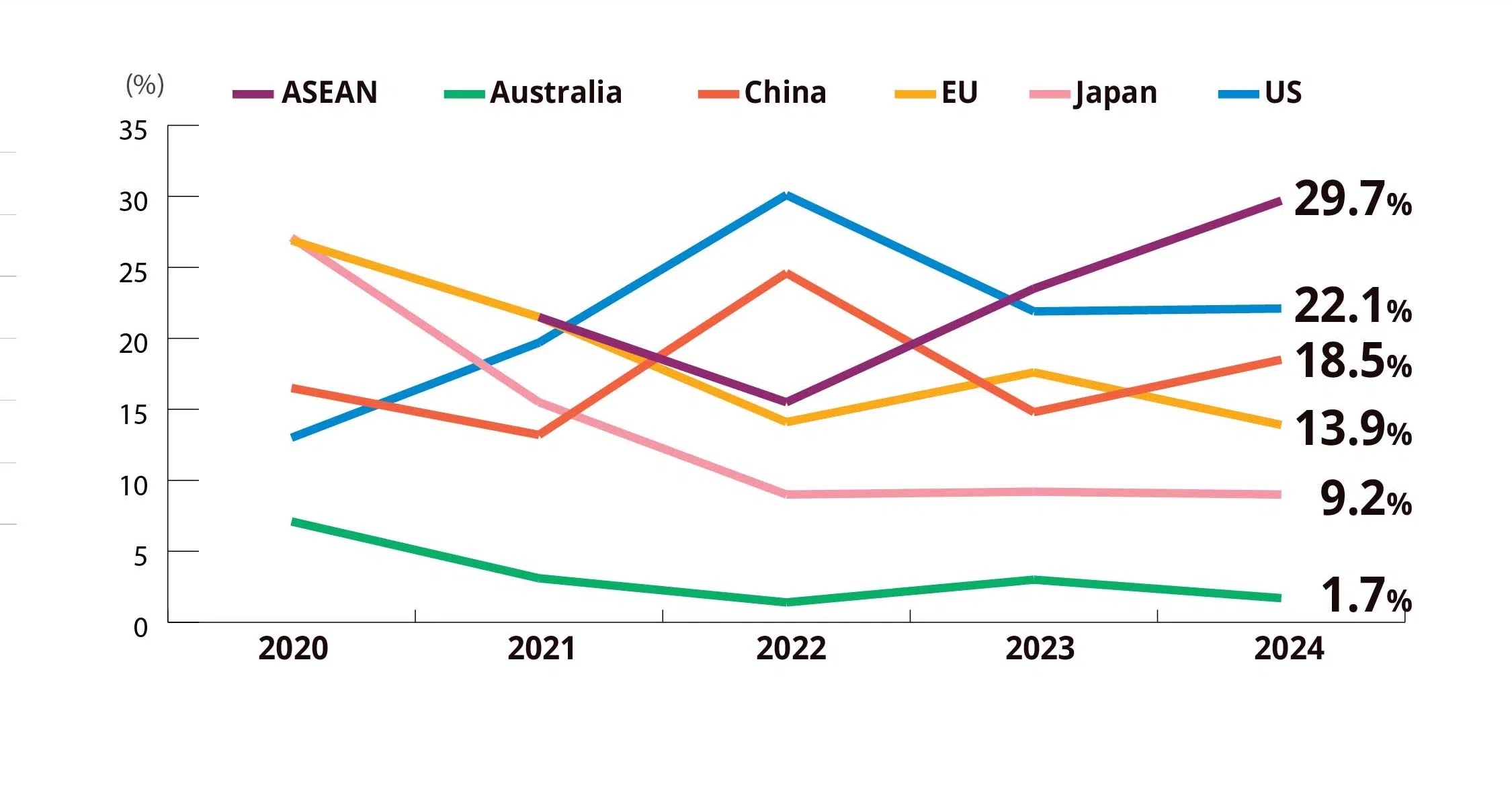

Much has been made of this year’s SSEA findings that if forced to choose, a very slim majority of the Southeast Asian respondents would prefer that ASEAN aligns with China rather than the US. This signifies a significant reversal of previous years’ trends.

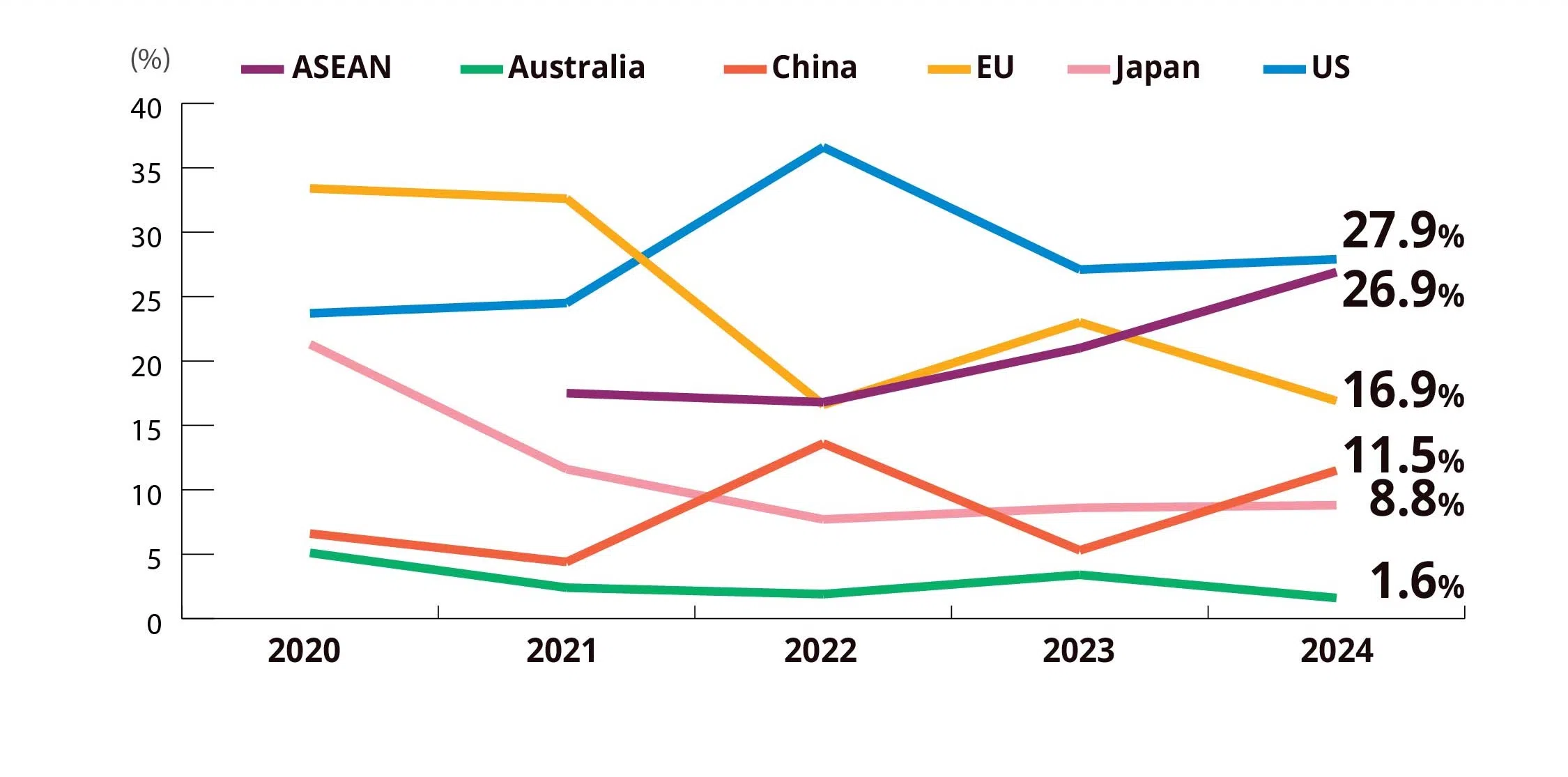

Since the question was first posed in 2020, there had been a strengthening trend towards preferring alignment with the US over China. The fact that this trend reversed in 2024 to the point where China has pipped the US for the first time is likely an indicator of deeper undercurrents concerning US leadership in the region.

Across Southeast Asia, there is a heightened sense of uncertainty over the future trajectory of US leadership amidst deepening polarisation in its domestic politics and the US presidential elections in November this year. In November 2023, the US failed to deliver on the digital trade pillar of the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF) due to opposition in Congress, accentuating concerns that Washington remains hamstrung in its economic engagement with Southeast Asia and the wider Indo-Pacific.

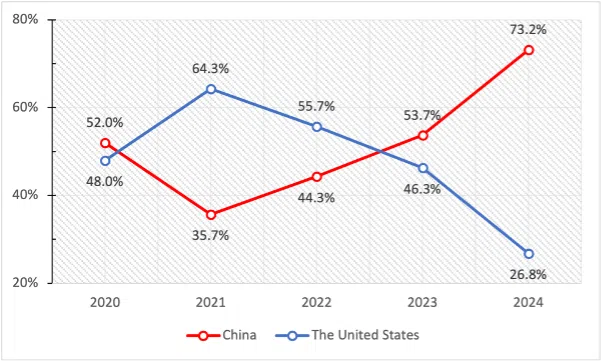

Significantly, the levels of support for China among the three Muslim-majority states in ASEAN — Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei — have strengthened significantly, with all three countries registering 15-20 percentage point increases in their level of support for aligning with China.

In all three countries, a whopping 70% or more of respondents said that they would prefer ASEAN to align with China rather than the US. This suggests the entrenchment of various relevant factors. Apart from the deepening economic ties with China in all three countries, the global spotlight on the Israel-Hamas conflict and the disproportionate number of casualties on the Palestinian side probably increased antipathy towards the US. The Palestinian cause and America’s traditional support for Israel have long been hot-button issues that shape perceptions of the US as being biased against the Muslim world and practising double-standards in global affairs.

The respondents were polled in January-February 2024 when sympathy for Israel was falling, and concerns about the humanitarian situation in Gaza were increasing. For Southeast Asian Muslims, the Palestine issue has become a visceral identity issue, not just a religious issue, that would predispose them to lean away from countries overtly supporting Israel.

Power perceptions

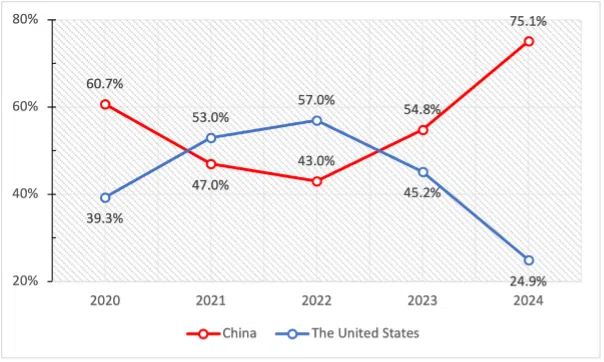

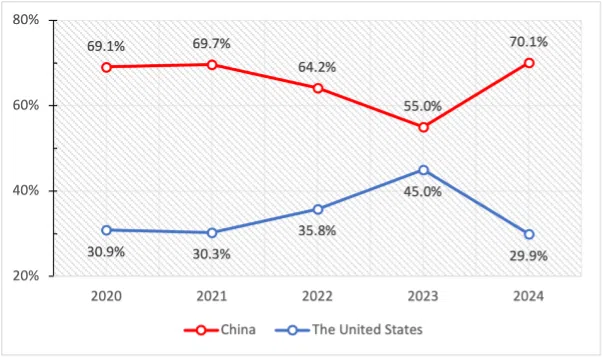

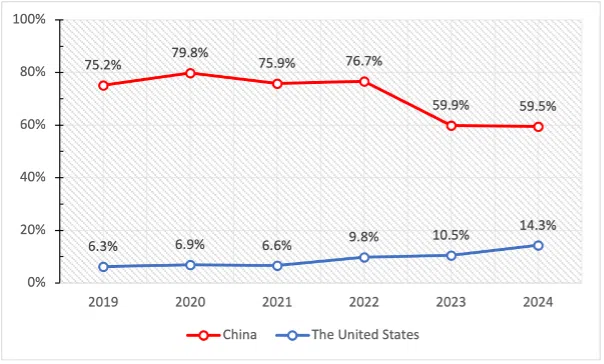

Multi-year data trends from the annual survey unequivocally show that China is perceived as the region’s most influential economic, political and strategic power. A clear majority of survey respondents consistently identify China as the region’s most influential economic power, although in the past two years, the percentage of respondents who think so has dropped quite significantly from around 75% to around 60%.

This perhaps reflects the ripple effects of China’s tough Covid-19 lockdown and its ongoing economic slowdown. Nevertheless, the region’s perceptions of America’s economic heft have always been significantly lower, usually in the single digits, though this has been creeping up slightly over the past two years. These perceptions belie the fact that the US remains a vital trading partner for the region and is still the largest source of foreign direct investment (FDI).

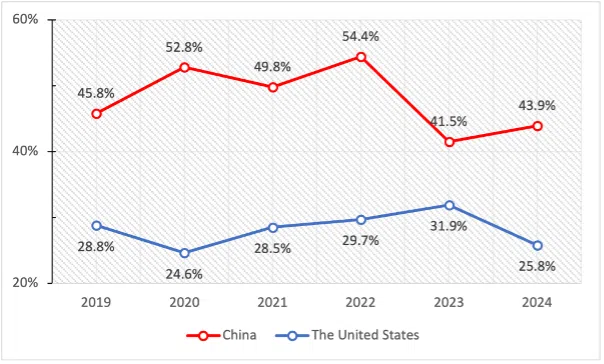

As for the region’s perceptions of who the pre-eminent political and strategic power is, it is somewhat of a surprise that survey respondents region-wide have consistently put China above the US despite the significant edge the US continues to enjoy over China in terms of military power and defence diplomacy activities (for example, China conducted 128 combined-military exercises in 2003-22, a mere 10% of America’s 1,113 exercises done in the same time period).

Perceptions of US influence trended fairly significantly downward in 2024, likely a reaction to concerns over Washington being distracted, by other geopolitical priorities such as the war in Ukraine and the Israel-Hamas conflict, and by domestic challenges.

Despite China being the region’s top trading partner, it is significant that survey respondents ASEAN-wide did not express high confidence that China could be counted on to champion the global free trade agenda.

Gap between power perceptions and regard for leadership

Yet preferences for China’s leadership in various aspects such as championing free trade, maintaining a rules-based order and upholding international law are consistently low. Despite China being the region’s top trading partner, it is significant that survey respondents ASEAN-wide did not express high confidence that China could be counted on to champion the global free trade agenda. Significantly, in light of the greater protectionist turn in the US, the region appears to increasingly pin hopes on ASEAN to pick up the mantle, signifying a desire for greater regional resilience and self-reliance.

For all of China’s peace-loving rhetoric on its non-hegemonic intentions and its vision of building “a community with a shared future for mankind” through various initiatives such as the Global Security Initiative, Global Development Initiative and Global Civilisation Initiative, the region consistently reflects a relatively dim view of China’s leadership in upholding the rules-based order. Generally, China comes in a distant fourth place compared to other countries and organisations such as the US, EU, Japan and ASEAN. Instead, there is still a strong preference for US leadership on this front.

A fundamental reason for this is that there remains a high degree of scepticism about China’s commitment to matching words with deeds. As demonstrated in the reactions to the Chinese defence minister’s remarks at the 2024 Shangri-La Dialogue, several participants called out the inconsistencies between China’s peaceable words and its aggressive deeds in the South China Sea.

At the discursive level, there is also a disconnect between China’s pledges to uphold international law and its advocacy of strengthening the authority of the United Nations, exemplified by its refusal to participate in and accept the judgement of a United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) dispute resolution process which ruled in 2016 that China’s nine-dash line claims in the South China Sea were incompatible with UNCLOS and therefore invalid.

From the Chinese perspective, the region’s continued preference for US leadership over China in upholding the rules-based order may also seem inconsistent and odd in light of the various examples of America’s own practice of exceptionalism in multilateral settings, notably America’s failure to ratify UNCLOS. But this inconsistency can be explained in terms of differences in regional threat perceptions of the US and China.

Unlike China, the US is not party to any of the region’s territorial disputes. Its presence in the region is therefore generally seen as more benign and a force for stability. Rather than feeling as “victims” of the US Navy’s Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOPs) in the region (as Chinese Defence Minister Admiral Dong Jun had put it at the recent Shangri-La Dialogue), US FONOPs have served to preserve a much-appreciated balance of power in the region.

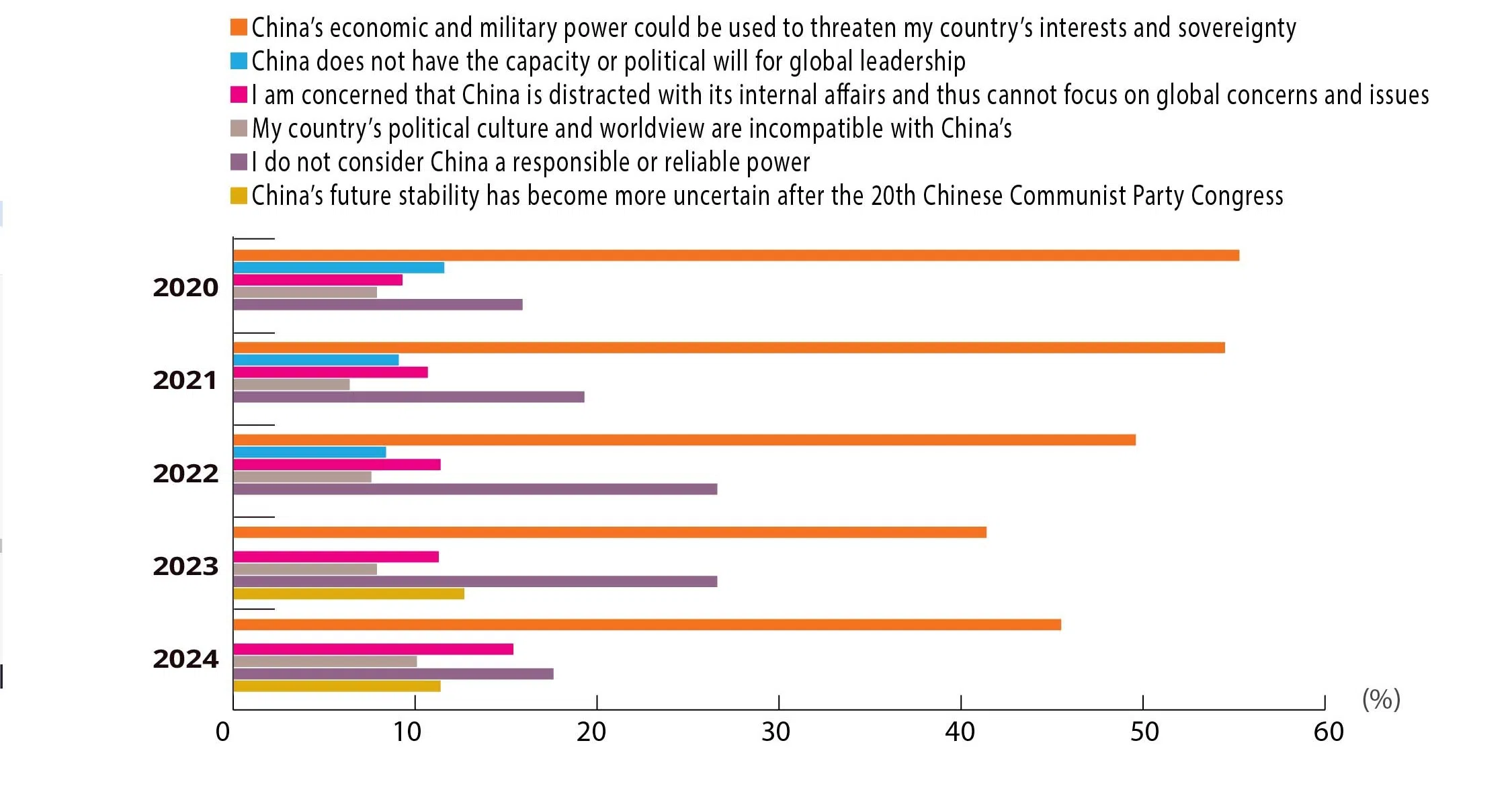

When asked why China was distrusted, the overwhelming answer region-wide was that China’s economic and military power could be used to threaten the respective ASEAN country’s interests and sovereignty.

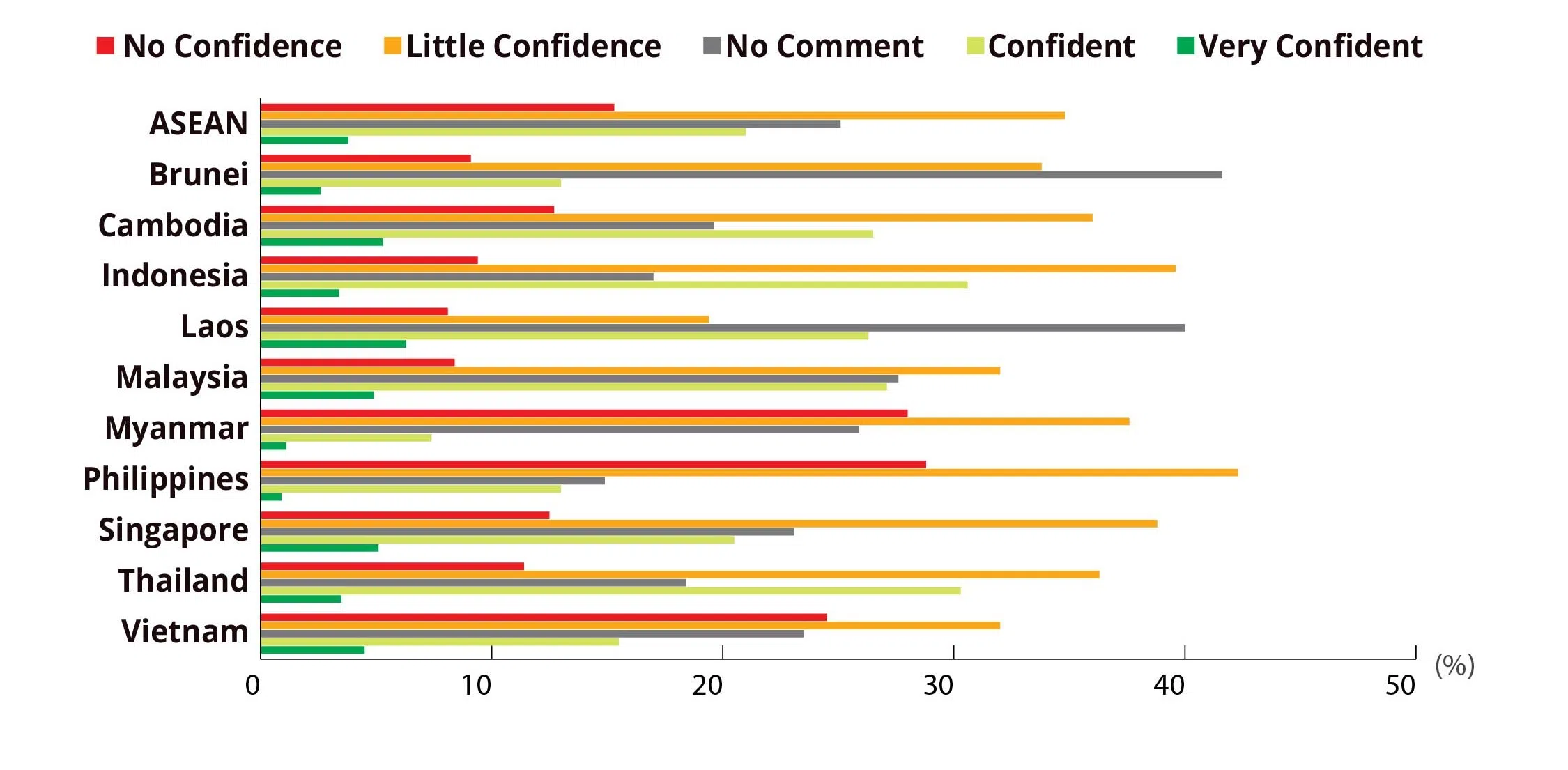

The region’s “fear factor” regarding China is reflected in the responses to the question about whether respondents believed China would “do the right thing” in contributing to global peace, security, prosperity and governance. It is significant that the majority of respondents in each country except Laos had no confidence that China would “do the right thing”. When asked why China was distrusted, the overwhelming answer region-wide was that China’s economic and military power could be used to threaten the respective ASEAN country’s interests and sovereignty.

Desire to keep the peace

But notwithstanding the doubts about China’s ability to play a positive leadership role, there is also a palpable desire among ASEAN member states to keep the peace with China. When asked about the outlook for bilateral relations with China over the next few years, the majority of respondents in seven out of ten ASEAN countries said they expected relations to improve. Only respondents from the Philippines said they expected relations to worsen, while respondents from Singapore and Myanmar expected relations to stay the same.

When asked for the top two measures China could take to improve its relations with regional states, the consensus was clear and consistent: China should seek to resolve outstanding maritime territorial disputes peacefully and in accordance with international law; and China should respect smaller countries’ sovereignty and agency.

... as the region finds itself increasingly forced to make binary choices between the US and China — especially in the areas of technology and critical supply chains — Beijing can likewise score strategic points if it can exercise temperance and restraint.

Implications: what should China do?

In his book The Prince, Niccolo Machiavelli famously said that it is safer to be feared than loved because love is preserved by the link of obligation which, owing to the baseness of men, is broken at every opportunity for partisan advantage, while fear preserves through dread of punishment, and that never fails. However, he went on to advise that a prince should inspire fear in such a way that, if he does not win love, he avoids hatred. These sayings hold some wisdom for Beijing.

The external environment has turned more hostile and challenging for Beijing in light of the hardening attitudes in US and Europe towards China, the intensifying competition in critical and emerging technologies, and, probably most concerning for Beijing, the recent election outcome in Taiwan which may have emboldened the island’s pro-independence movement.

Under these circumstances, it is tempting for Beijing to lash out and play a strong defence by going on the offence, and to demonstrate its ability to “punish” those who seek to cross its “red lines”. But this could be counter-productive in the long term, and risks touching off a regional security dilemma in which one country’s defensive preparations are seen as threatening to the other.

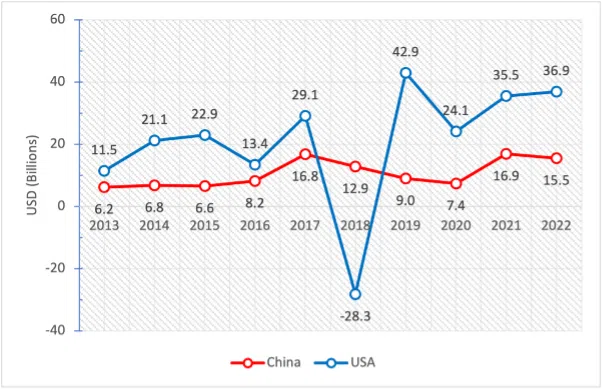

Instead, it may serve Beijing better to remember that during the 1997-98 Asian Financial Crisis, and similarly at the height of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008, China accrued a significant amount of goodwill by not devaluing its currency, the Yuan.

Between late 2008 and June 2010, China’s central bank effectively held the US dollar-yuan rate at 6.83. This reflected Beijing’s desire to maintain currency stability amid economic and financial uncertainties, even in the face of domestic pressures to depreciate the Yuan. In 1997-98, China had also provided Thailand and other Asian countries with US$4 billion via bilateral channels within International Monetary Fund frameworks. China was seen then as a “responsible” and central actor in stabilising the regional economic environment.

Today, as the region finds itself increasingly forced to make binary choices between the US and China — especially in the areas of technology and critical supply chains — Beijing can likewise score strategic points if it can exercise temperance and restraint. It could, for instance, choose to take the moral high ground and not go tit-for-tat with the US on trade tariffs — similar to what President Xi did in the wake of Trump’s withdrawal from the Trans Pacific Partnership in 2017.

It has scored points against the US and other Western powers by pointing out the many instances of their double standards and hypocrisy. However, China should not add to global cynicism by wielding its growing power and influence no differently in the region.

Back then, President Xi took a high-profile swipe at Trump at the World Economic Forum, affirming the benefits of globalisation and the need to “reaffirm unambiguously” the need for open markets and rules-based trade. After President Biden raised tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles and solar cells in May 2024, Chinese trade experts reportedly urged President Xi to exercise caution and take “the moral high ground”, lest a tit-for-tat cycle hurts the slowing global economy.

China should continue to demonstrate support for the developmental needs of the region and Global South. Already, China’s Global Development Initiative has been backed by Southeast Asian countries, which see it contributing to their development and China upping its regional economic engagement. More importantly, China could demonstrate its commitment to de-escalate tensions and the potential for conflict over disputed territories, even if a lasting conflict resolution in accordance with international law remains a distant goal.

The region has been telegraphing a consistent message to China: a large part of the reason why China is more feared than loved is because there is still little confidence among Southeast Asians that China will rise in a manner that would see it playing a stabilising role in the region in the long term.

Now that the mood in the US appears to be turning ever more insular and protectionist, a window of opportunity for China exists. It has scored points against the US and other Western powers by pointing out the many instances of their double standards and hypocrisy. However, China should not add to global cynicism by wielding its growing power and influence no differently in the region.

This article was first published in Fulcrum, ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute’s blogsite.

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)