Trump, the Panama Canal and US-China rivalry

As China’s economic presence has grown, it is not surprising that Trump’s interest in reclaiming the Panama Canal is a mere smokescreen for the larger geopolitical contest between the US and China in the western hemisphere, says US academic Chen Xiangming.

From the list of things on his sweeping and disruptive new agenda, ticked off by the returned US President Donald Trump in his inauguration speech, this line stood out: “And above all, China is operating the Panama Canal. And we didn’t give it to China; we gave it to Panama, and we’re taking it back.”

This single indirect mention of China may be somewhat surprising. Conventional wisdom would lead many to expect more direct references to China given the central focus on competition with China for US foreign policy. How to read Trump’s real intent behind his expansionist idea of taking back the Panama Canal? It is a bit puzzling considering that Trump had commented on a positive phone call with President Xi Jinping just before his inauguration, which was attended by Chinese Vice-President Han Zheng, a friendly political gesture by China.

Past is prologue

There is both a geoeconomic and geopolitical dimension to a potential US-China tussle over the Panama Canal-related interests. It should be seen via a long historical lens on the origin and evolution of the Panama-US tension over the canal. The US completed the construction of the Panama Canal in 1914 at a cost that may amount to multiple billions in today’s US dollar while losing thousands of American workers to mosquito bites and other tropical diseases during the construction.

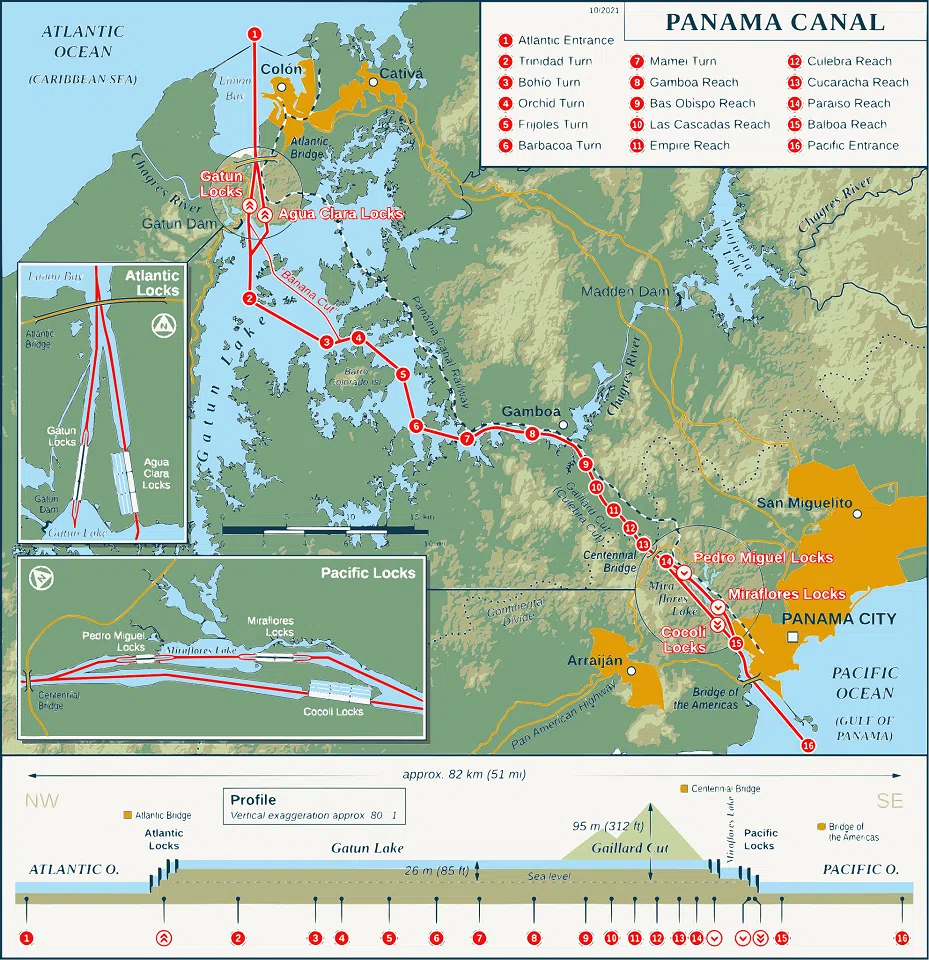

The US has been the largest user and beneficiary of the Panama Canal as over 70% of its through-cargoes flow to and from the US east and west coasts. The canal, however, is also a crucial passage for global maritime logistics flows. In moving around 6% of global trade, the canal shortens the shipping distance between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans by thousands of nautical miles while reducing considerable shipping costs relative to sailing around Cape Horn or the Strait of Magellan in southern Chile.

Hardly legitimate or realistic, Trump’s vow to take back the Panama Canal rests on his ill-informed gripe about the history of twists and turns in the Panama Canal’s development, ownership and operation.

Hardly legitimate or realistic, Trump’s vow to take back the Panama Canal rests on his ill-informed gripe about the history of twists and turns in the Panama Canal’s development, ownership and operation. A brief recount of this not widely known history reveals the protracted presence of geopolitical and geoeconomic competitions between old strong and new great powers regarding the canal and its related interests in the Caribbean region and beyond.

In 1902, the US bought the right to develop the Panama Canal from a failing French company partly to thwart France’s already waning influence in the region. In November 1903, the US helped Panama become independent from Columbia using its military muscle. Two weeks later, the US and the new Panamanian government signed the Hay-Bunau-Varilla Treaty, establishing permanent US rights to a Panama Canal Zone.

Jimmy Carter and Omar Torrijos at the signing of the Panama Canal Treaty. (Wikimedia)

Fast forward to 1977, President Jimmy Carter signed The Treaty Concerning the Permanent Neutrality and Operation of the Panama Canal, or the Neutrality Treaty, and The Panama Canal Treaty, which stated that the Panama Canal Zone would cease to exist on 1 October 1979, and the canal itself would be turned over to Panama on 31 December 1999. Both were ratified by the US Senate in 1978.

Trump saw this as a give-away, symbolised by the one-US-dollar transfer payment, of an extremely valuable US asset to Panama. He complained that Panama not only was ungrateful for becoming independent under US military assistance back in 1902 but also has been unfair in charging US commercial and naval ships passing through the canal over the past quarter of a century. In reality, the Panama Canal operator charges all passing ships based on size and other specifications according to the “just, reasonable, and equitable” clause in the signed treaty. Trump would be drooling over the huge revenue and profit from the canal that could be imagined as under US control.

While China certainly does not operate the Panama Canal as Trump said it does, its footprint in Panama has grown since 2017...

The real bone of contention

As Trump appears to focus on the US business interest in the Panama Canal, he may be equally, if not more, concerned about China’s strong involvement in Panama and the canal, as another theatre of great-power rivalry, this time in the US backyard.

While China certainly does not operate the Panama Canal as Trump said it does, its footprint in Panama has grown since 2017 when Panama turned away from Taiwan to China as the official diplomatic partner and joined the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2018, the first Latin American country to do so. This resulted in the promised projects of a high-speed rail, a metro line in Panama City, a container port and a US$1.4 billion fourth bridge over the Panama Canal, all agreed under the former Panamanian President Juan Carlos Varela who met Xi Jinping in 2018.

... Chinese presence has already taken root through the 25-year operational control of the ports at both the Atlantic and Pacific entrances to the Panama Canal...

Subsequent Panamanian presidents have suspended or delayed these projects partly due to the US pressure and partly under suspected corruption involving a Chinese builder. In 2023, momentum picked again for the bridge over the canal after both sides signed a contract addendum to get the project restarted. If built and completed, the 1,120-m-long two-tower cable-stay bridge will be located north of the Bridge of the Americas at the Pacific entrance to the Panama Canal.

In the meantime, Chinese presence has already taken root through the 25-year operational control of the ports at both the Atlantic and Pacific entrances to the Panama Canal by CK Hutchison owned by Hong Kong billionaire Li Ka-shing. The Chinese conglomerate Landbridge Group has taken equity control of the Port of Panama, Panama’s largest port located on the Atlantic side. This scale of Chinese investment looks to the US as potential control of the canal at the likely expense of US interests.

As China’s economic presence has grown, it is not surprising that Trump’s interest in reclaiming the Panama Canal is a mere smokescreen for the larger geopolitical contest between the US and China in the western hemisphere. This is nicely captured by the front page of New York Post on 8 January with the headline “The Donroe Doctrine”. In a similar spirit, former US Congressman Matt Gaetz, a Trump loyalist, posted on X about taking Panama Canal back from China rather than from Panama itself. Trump’s stance toward the Panama Canal has also prompted a China-based WeChat platform to refer to it as an American version of the “Taiwan question” in terms of claiming sovereignty.

... US-China competition for geopolitical and geoeconomic interests in Latin America including the Caribbean will remain heated as China widens its footprint in the region...

Finally, Trump’s rhetoric about taking back the Panama Canal has been met by a mixture of disbelief, despisal and most importantly, defiance from the Panamanian government, although it has just opened a financial and compliance review of the Hong Kong company operating the ports at either end of the Panama Canal amid Trump’s threat including a reserved use of military force to retake the canal. While it is unclear if this one-sided claim will go anywhere, it is certain that the US-China competition for geopolitical and geoeconomic interests in Latin America including the Caribbean will remain heated as China widens its footprint in the region evidenced by the recent opening of China-built Port of Chancay in Peru in December 2024, against some complaint from the US. The Panama Canal game will unfold with the US and China as main players.