US pivot to Asia: Managing relationship with China crucial

While the Americans have made noticeable progress in their "pivot" to Asia, the crux of successful regional engagement rests on Washington's ability to work with and around China's indisputable links and influence in this part of the world, while managing its own relationship with Beijing.

In November 2011, the Obama administration declared a historic "pivot" to Asia, a strategic rebalancing of the US's resources and priorities to the region. Eleven years on and two presidential administrations later, the pivot has gained some legs.

Two years into the presidency of US President Joe Biden, Washington has gone back to basics, harnessing the power of alliances and partnerships in pursuing American goals. Former Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi summed this up beautifully as Washington's "5-4-3-2-1" approach, focused on the Five Eyes intelligence network, the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue or Quad (involving the US, Australia, Japan and India), the AUKUS trilateral arrangement (the US, UK and Australia), Washington's bilateral relationships in the region and last, the US's position in the Indo-Pacific.

Long pilloried for its withdrawal from the 12-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership, Washington has advocated the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework (IPEF), centred on pillars such as digital trade, resilient supply chains, and tackling climate change. Last year, Washington upgraded its relationship with ASEAN to a comprehensive strategic partnership.

On the flip side, Washington is sticking to its guns on a range of policies in four areas that have evoked some concerns. This does not augur well for its regional engagement going forward.

Washington's curbs on technological exports to China - primarily in semiconductors - have not been warmly received in Asia.

Released in October 2022, a central theme of the US National Security Strategy (NSS 2022) is the defining battle between democracies and autocracies. While this would go down well with voters at home and the US's European allies, it will be a hard sell in Asia, given the region's variegated political systems.

Second, Washington's curbs on technological exports to China - primarily in semiconductors - have not been warmly received in Asia. The logic is simple: decoupling is unwelcome, given the deep economic linkages that all regional countries have with Beijing.

Third, without market access, the IPEF is a poor substitute for ambitious free trade agreements (FTAs) such as the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP).

Last, the US and its allies might not appreciate the concerns of small and medium nation-states in Southeast Asia as they witness the growing Sino-US rivalry. While regional states do understand that US-led initiatives such as the Quad and AUKUS seek to manage China's growing power, they are concerned about the implications, especially a Sino-US armed conflict or skirmish, be it over Taiwan or in the South China Sea.

Perhaps a mid-course correction is in order.

US-China decoupling not welcome in the region

Of the four areas, little can be done to reorient the US's emphasis on democracy promotion, particularly for Democratic administrations like Biden's, which are traditionally more bound to promote such values.

On decoupling, the US should at least recognise that its actions smack of protectionism. It does not look good for a superpower which claims to support the rules-based international order.

On decoupling, the US should at least recognise that its actions smack of protectionism. It does not look good for a superpower which claims to support the rules-based international order. What is more, decoupling is paired with a subsidies-driven industrial policy which seeks to compel companies to base their manufacturing operations in the US. As Zack Cooper notes, decoupling and industrial policies could strengthen global economic rules if they were coordinated with allies and partners; if conducted by the US unilaterally, these two tools could lead to worse tensions.

There are limits to decoupling. Despite US efforts to get regional countries to reduce their dependence on China, China-ASEAN trade has grown 71% since July 2018, when the US slapped tariffs on a range of Chinese goods. This reflects the bonds between smaller ASEAN economies and China's dominant role in regional and global supply chains.

That seven out of ten ASEAN countries signed up to IPEF talks (despite there being no promise of market access) underscores the region's desire for Washington to be economically engaged with it.

Despite the difficult domestic politics in the US associated with signing new FTAs, Washington can gain leverage by at least acknowledging that it aspires to rejoin the CPTPP. After the US withdrew from the TPP, its regional partners forged ahead with the CPTPP (which China asked to join) and the RCEP. That seven out of ten ASEAN countries signed up to IPEF talks (despite there being no promise of market access) underscores the region's desire for Washington to be economically engaged with it.

The IPEF is not enough, however. The Asia Society Policy Institute recently suggested a path forward: modifying the CPTPP to cater to US interests and facilitate Washington's re-entry. This would involve 12 areas, such as improving rules of origin for cars and trucks, and strengthening labour provisions, and conditions to protect the environment.

Given that US-led initiatives to manage Chinese power have led to regional concerns about inadvertent escalation into conflict, the US needs to further engage China to keep temperatures down.

Deeper engagement from the US needed

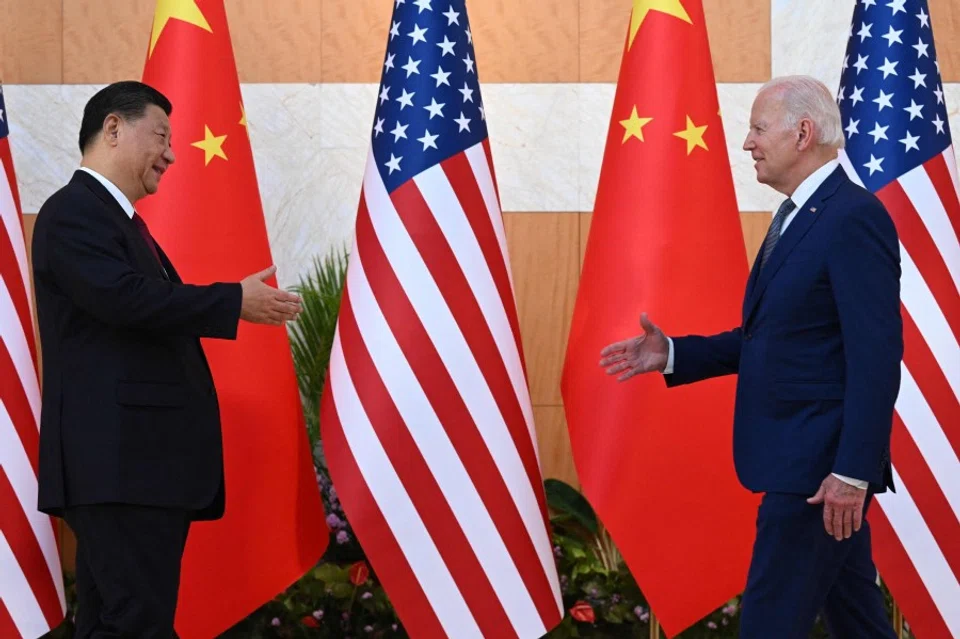

There has been some progress here. In November 2022, President Biden met his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping in Bali on the sidelines of the G20 summit and discussed several topics, from Taiwan to the war in Ukraine. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken's visit to Beijing will take place on 5 February 2023, fulfilling Biden's promise to Xi to keep "lines of communication open".

... Washington needs to continue to engage the region strategically and economically, while avoiding inadvertent escalation amid ongoing tensions with China.

New Chinese Foreign Minister Qin Gang, formerly China's ambassador to Washington DC, has pledged to improve the bilateral relationship. He takes a softer tone compared to China's dwindling number of "wolf warriors", but there is no certainty that Chinese policy towards the US will change. Qin does not call the shots and his appointment might not result in any discernible shift in China's foreign policy. Nevertheless, it behoves the US and China to resume dialogue and leverage their crisis management measures for regional stability.

The US has come some way in upping its regional engagement since the Obama years. To avoid making divots in the pivot, however, Washington needs to continue to engage the region strategically and economically, while avoiding inadvertent escalation amid ongoing tensions with China.

This article was first published by ISEAS - Yusof Ishak Institute as a Fulcrum commentary.

Related: Why China has no choice but to challenge the US's grand strategy | Can the US keep its promises in Southeast Asia? | Strategic Competition Act: The US targeting China through Cold War politics? | China gearing up for intense competition in the Pacific | America turning to state intervention to win US-China tech war

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)