In pursuit of ideals and love: The William Shakespeare of Chinese drama, Tang Xianzu

Ming dynasty playwright Tang Xianzu (汤显祖, 1550-1616) is quite the celebrity these days. Often adapted into stage plays, his seminal work The Peony Pavilion (《牡丹亭》) is helping to spur the revival of Kunqu (昆曲, Kun opera). The Peony Pavilion (Young Lovers' Edition) for instance, produced by Pai Hsien-yung and performed by young actors of the Suzhou Kunqu Opera Theatre, not only created a sensation on both sides of the Taiwan Strait but also piqued the younger generation's interest in Kunqu and of Tang Xianzu.

A young friend of mine made this observation: Tang Xianzu was a great playwright who lived in the same era and even died in the same year as William Shakespeare. In fact, the two can be called lighthouses illuminating Eastern and Western literature and drama.

However, the entry on Tang Xianzu in the History of Ming (《明史》) is short and simple. How could the write-up not mention that Tang was also a master dramatist? How could it leave out his masterpiece, Four Dreams in the Camellia Hall, which is a collection of four operas including The Peony Pavilion?

Tang is listed in the book under "Literati", which clearly denotes that he was a writer. Yet why is there an extensive discussion of his criticisms against government corruption in "On Grand Secretaries and Censors" (Lun fuchen kechen shu 论辅臣科臣疏), which is a political essay? It is not even a literary work of his. Why is this so?

To the ancient ruling elites, the literary arts that we hold in high regard today were but insignificant skills unworthy of mention. This stance was not unique to China - Britain was the same too.

I replied that it was not until modern times that literature became regarded as a great undertaking. This is a by-product of social democratisation and diversification. Although Cao Pi (187-226) said in his Essay on Literature (《典论论文》, written during the Wei Jin period), that "literature relates to the great mission of governance and is an everlasting grand cause", the type of "literature" that Cao referred to included all types of writing including political commentaries. It is not what we would refer to today as the literary arts.

When the ancient people recorded history, especially official history, they focused on national affairs or politics. To the ancient ruling elites, the literary arts that we hold in high regard today were but insignificant skills unworthy of mention. This stance was not unique to China - Britain was the same too. Shakespeare is absent from the annals of 17th century British history, and is completely without historical status. In a sense, he is even worse off than Tang, who at least has a biographical chapter in the History of Ming.

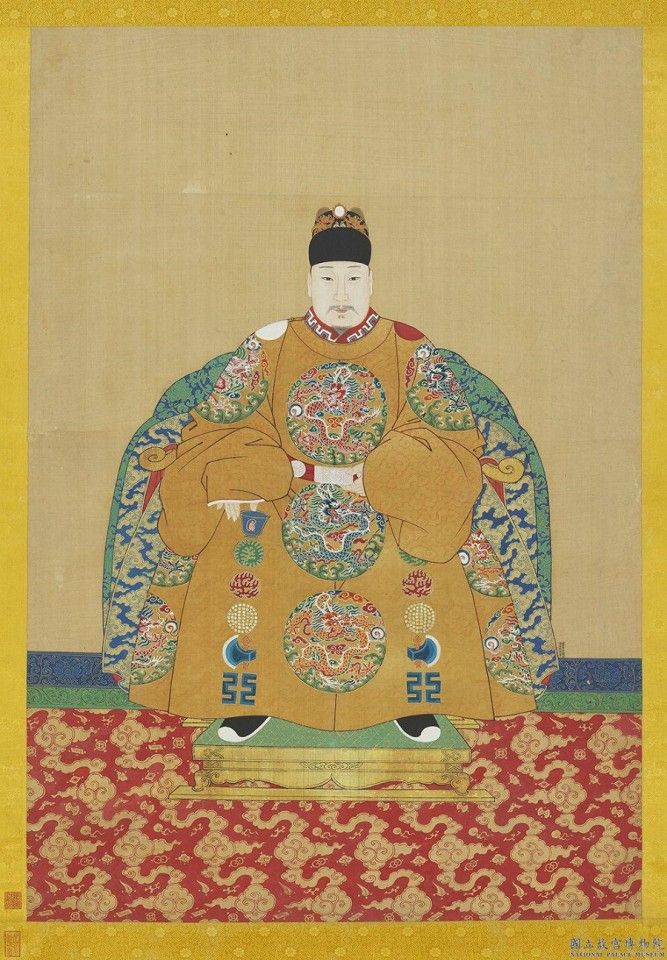

Tang Xianzu the man

However, there is indeed a story to be told regarding Tang's aforementioned political essay against corruption (Lun fuchen kechen shu). The essay not only illustrated the political climate during the Wanli Emperor's reign, but also shed light on Tang's character: he was forthright and liked to do things his way. But people back then thought that he was a difficult and egoistic person just because he was so talented. He was different and stuck out like a sore thumb. His words and actions were often controversial, and his career as an official was also ruined because of what he said.

Actually, plenty of difficult and egoistic characters lived during the Ming dynasty and throughout the ancient times. So why did Tang attract so much attention? To answer this question, we have to go back to his youth.

Tang was smart, talented and outstanding. He successfully participated in the provincial examinations in his early 20s and became highly sought after by rulers. One of them was the chief grand secretary Zhang Juzheng who served under the Wanli Emperor. However, Tang wasn't the least bit impressed. Putting aside the fact that he refused to call on Zhang, he deliberately fobbed off Zhang's invitations and visits multiple times, which was very disrespectful. Perhaps this was the reason why Tang failed the imperial examinations thrice over the next decade that Zhang was in power. It was not until Zhang passed away that Tang finally passed the examinations in 1583 at the age of 34.

He (Tang Xianzu) continued to insist on doing things his way and even distanced himself from the centre of power to prove his righteousness and integrity.

Although Tang passed the imperial examinations and became an official, his attitude and behaviour remained unchanged. He continued to insist on doing things his way and even distanced himself from the centre of power to prove his righteousness and integrity. He rejected positions that could lead him on the fast track to promotions, choosing instead to become an official in Nanjing and focusing his energy on poetry and drama.

In the 14th year of the Wanli Emperor's reign (1586), he wrote the poem "Thirty Seven" on his 37th birthday, recounting his experiences thus far. Loosely translated, it reads: "In my youth, I was particularly bright and outstanding among my scholar peers. When I was around 20, I was in my prime. I made my mark in a beautiful city and loved to interact with the righteous, the upright, and the philanthropic. I am a man of righteous character and believe I can use my talents in governance. While China's situation is serious, it can be solved with a few strategies. However, I do not want to stay a bureaucrat forever, as there are many other meaningful pursuits in life. It's a pity I realised this too late, and youth has passed in the blink of an eye. I am a mid-level official in an insignificant region. When can I be the chief of a prefecture? I am already 37. My ambitions have eroded with time and it's the depressing season of autumn now. I should be doing great things. On the spur of the moment, I might criticise the government. I may not be on par with ancient sages, but I want to at least match my peers."

During his three to four years in politics, he sat on the sidelines and saw his ambitions erode with time.

Yearning for something more

This poem is very interesting. It not only recounts Tang's dazzling youthful days, but shows what reflections he had on his life choices when he was nearing middle age. As a believer of Confucianism, one must bring good to people and the world. One must pass the imperial examinations, build a career and serve the people. With his intelligence and wisdom, and his ambition and dream to govern the country, Tang believed that "while China's situation is serious, it can be solved with a few strategies".

However, while this was what Tang wanted to achieve guided by his Confucian beliefs, it was not his ultimate goal. He was convinced that there were "many other meaningful pursuits in life" - that is, discovering and pursuing the beauty and meaning of life through literary works, and using his intelligence and wisdom to make a statement. During his three to four years in politics, he sat on the sidelines and saw his ambitions erode with time, wanting to resign even when he was still in his prime. He thought of writing to the court to criticise the state of affairs, knowing that it would stir trouble for himself and the rulers.

His birthday reflections, especially on criticising the government on the spur of the moment, was a self-fulfilling prophecy. In the following years, as Tang could no longer suppress his yearnings and impulses and firmly insisted on staying true to himself and to the choices that he made, a head-on confrontation finally erupted between him and the dog-eat-dog world of officialdom.

When Tang was 38 years old, he headed to Beijing for his assessment and evaluation as an official (京察考核). While he was there, officials spread rumours about Tang criticising the government. He was also allegedly writing a satirical play to mock the court and the illustrious officials.

The quest to stay true to oneself

When he was back at his office in Nanjing, Tang wrote a poem about his experience (《京察后小述》Jingcha hou xiaoshu) and lamented about man's sinister intentions and the malicious slander thrown at him. The poem goes something like this: "First it was the young who were criticising me like barking dogs. Then the old chimed in. They spread rumours about me and attacked me. But I can't be bothered. I will stay true to myself. I will not change who I am according to others' opinions."

He went on to make a vow to himself along these lines: "I will write groundbreaking essays, and achieve great things that will shock the world. I will indulge in poetry, wine, and dance. I will yawn at the inconsequential and turn my back at banquets to humble and humiliate the powerful."

"Such is the true state of our society: the genuine and upright rarely live good lives, while the hypocritical and deceitful live prosperous ones." - Tang Xianzu

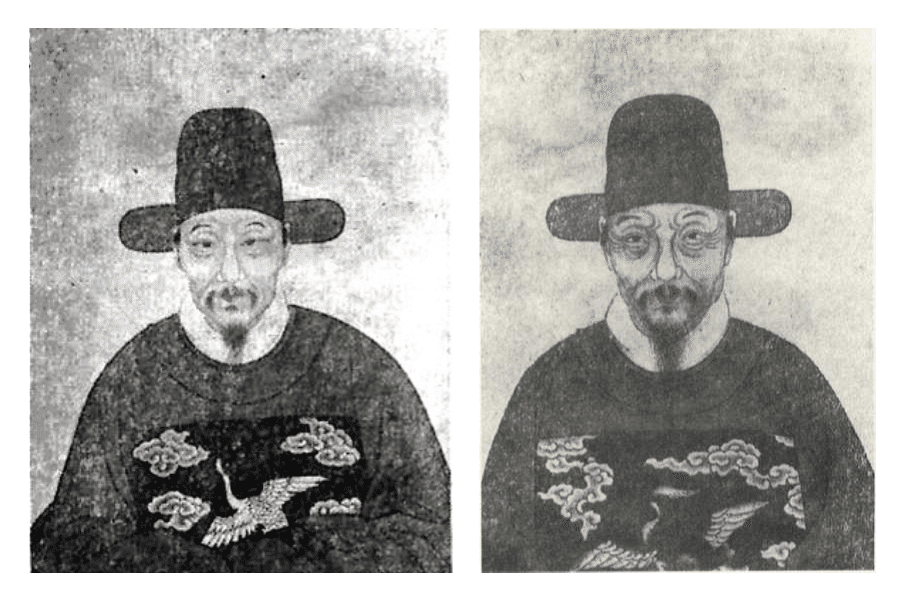

Strong words, but Tang once wrote a letter to his friend Wang Kentang (王肯堂, a government official and physician). He said some hypocrites had distorted and circulated political views that he had shared in private. He protested: "I dare not say I'm a saint, but I am a genuine and upright person. There are two illustrious persons from a city in the South who are hypocrites. I was objectively discussing state affairs with them, but they took things out of context and spread rumours about me, almost getting me into big trouble. Such hypocrites are plentiful. While they are fully able to discuss state affairs, truth and falsehoods are no longer discernible under the current way of governance. Such is the true state of our society: the genuine and upright rarely live good lives, while the hypocritical and deceitful live prosperous ones."

Tang could only cry out in exasperation about the fact that there were such "hypocrites" who blatantly deceived the masses and still kept their place in this world. While Tang did not mention names, taking reference from what he had gone through, it is highly likely that the "two illustrious but hypocritical persons" he talked about referred to the Wang brothers - Wang Shizhen and Wang Shimao - Nanjing's literary and political leaders back then.

Tang's travels deep into the regions right by the South China Sea allowed him to experience Lingnan's wonders, and showed him the things that he had never seen before. His experience in Lingnan also provided him with the background knowledge for his masterpiece, The Peony Pavilion.

Leaving behind a message of hope

A few years later in the 19th year of Wanli Emperor's reign (1591), the 42-year-old Tang finally had enough of corrupt officialdom and penned his famous essay on corruption, Lun fuchen kechen shu. This essay got him into big trouble and he was given the empty title of dianshi (典史) and was banished to Xuwen in Guangdong's Leizhou peninsula.

While Tang's trip to Leizhou peninsula lasted under a year; it brought him out of the Mei Pass ( 梅关, a strategic site situated in the Meiling Mountains of Guangdong which forms the boundary between the provinces of Jiangxi and Guangdong) and into the border regions of Lingnan. In fact, his travels to Leizhou and Hainan were just like the trips that Su Shi (苏轼, Song dynasty politician and poet) had taken. Tang's travels deep into the regions right by the South China Sea allowed him to experience Lingnan's wonders, and showed him the things that he had never seen before. His experience in Lingnan also provided him with the background knowledge for his masterpiece, The Peony Pavilion.

Tang's biographical chapter in the History of Ming recorded his essay to the emperor and his criticisms of the court, which landed him in big trouble. While his biography was related to the setbacks and frustrations he faced, and while they were not entirely cynical about the world, they still portrayed his immense displeasure with a world where "the hypocritical and deceitful lived prosperous lives". Following his banishment, he created the passionate world of The Peony Pavilion. In the story of the pursuit of ideals and love, Tang left behind something beautiful for people to aspire to.