Reflections by George Yeo: Celebrating 30 years of diplomatic relations between Singapore and China

In 2018, China celebrated the 40th anniversary of Deng Xiaoping's new policy of reform and opening up. In those 40 years, China's economy grew roughly 50 times in US dollars, 200 times in RMB and about 90 times in terms of purchasing power parity (PPP). Although the bulk of the effort was made by the Chinese people themselves, China was also helped by foreign assistance. Ten foreigners were awarded the China Reform Friendship Medal in 2018 for making a signal contribution to China's astonishing transformation during this period. One of the recipients was Singapore's Lee Kuan Yew. The process of selecting the ten individuals for the medal must have been elaborate and controversial. A large pool of candidates would have been carefully considered. The selection having been made and announced to the world, the list is forever recorded in Chinese history.

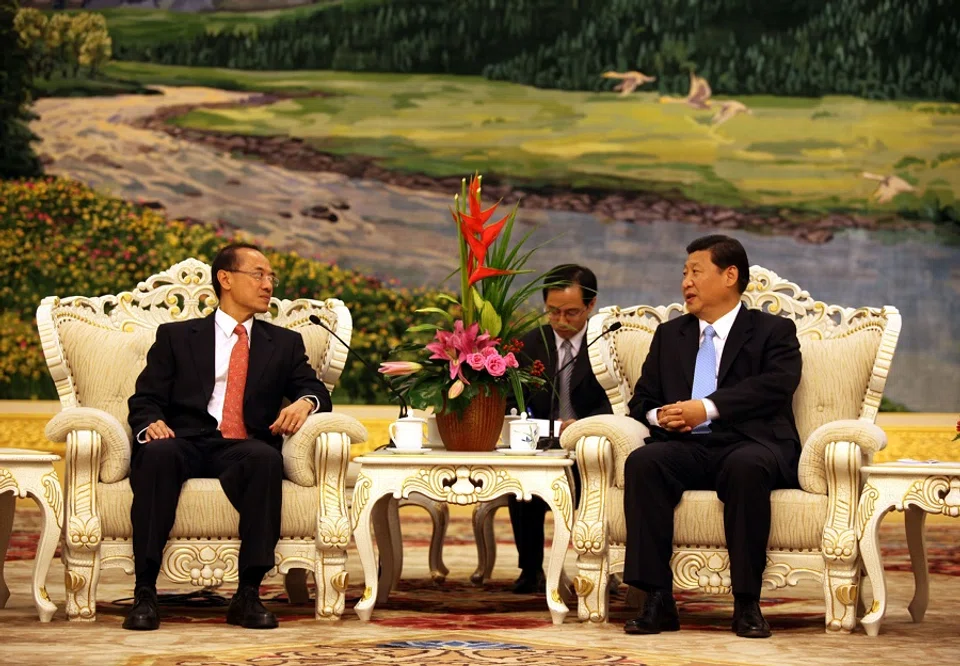

This year, we celebrate the 30th anniversary of diplomatic relations between Singapore and China. Diplomatic relations were a necessary formality. Lee Kuan Yew had told Taiwan President Chiang Ching-kuo much earlier that when that day came, Singapore's one-China policy required the state symbols of the Republic of China in Singapore to be taken down. Significantly, Beijing noted without objection the use of training facilities in Taiwan by the Singapore Armed Forces. Indeed, Singapore's unofficial relationship with Taiwan made possible the talks between Wang Daohan and Koo Chen-fu in 1993 and those between Xi Jinping and Ma Ying-jeou in 2015, both of which were critical milestones in cross-strait relations.

Singapore's role in the last 40 years

Singapore's unusual role in the drama of China's great revival has its roots in the history of China's interaction with Southeast Asia over the centuries. It is Singapore's "Chinese-ness" as an independent sovereign country (and not only as a trading post like Penang) which makes Singapore of especial interest to China. Singapore's success as a young country caught the eye of Deng Xiaoping when he steered China in a new direction in 1978. During his visit to Singapore in November that year, Lee Kuan Yew remarked that if Singapore with a population three-quarters Chinese, many of whom were descendants of coolies, could achieve a certain level of development, how much more could China with its long history and vast talent.

In 1985, China's State Council appointed Goh Keng Swee as an economic adviser on coastal development and tourism. Singapore was an inspiration to Deng. On his famous Southern Tour of 1992, Deng remarked that in social management, China should try to learn from and do better than Singapore. Like Dazhai for agriculture and Daqing for industry, Singapore quickly became a pilgrimage destination for reform and opening up. That year, scores of Chinese delegations visited Singapore. It was an honour for Singapore but many agencies were overburdened. Lee Kuan Yew then made a proposal to Chinese leaders for the two countries to work together on a joint project. Chinese officials could abstract from Singapore's positive and negative experiences while Singapore officials would benefit from understanding China's conditions more deeply. That was the spark which ignited Suzhou Industrial Park, Tianjin Eco-City, the China-Singapore (Chongqing) Connectivity Initiative and a number of other joint undertakings.

During the 90s, Singapore was an essential case study in China for economic development, social management and urban planning. Lee Kuan Yew directed that special courses be organised for Chinese officials in Singapore universities. Their alumni now number in the thousands, some among whom currently hold high positions. Not long after Deng's famous remarks, Vice Minister of Propaganda Xu Weicheng led a delegation on a ten-day study visit to Singapore, following which he wrote a short primer on this curious predominantly Chinese city-state. It became a classic of how China viewed Singapore at that time.

Internally, there must have been furious debate about loss of control to external influence and manipulation. The study of little Singapore gave some assurance.

In 1995, Ding Guangen, Politburo member responsible for all aspects of public communication and an old intimate of Deng Xiaoping, spent over a week in Singapore with a high-level ministerial delegation. As the minister for information and the arts, I was their host. They worked mornings, afternoons and evenings, taking no time off for shopping or sightseeing. Every aspect of public communications in Singapore was studied with care - bookshops, cinema halls, public libraries, museums, newspapers, radio, television, and the internet which was then in its infancy. They called on Lee Kuan Yew, Goh Chok Tong and others. They quizzed me on the use of the internet and its effects on society. I replied that the internet could always be regulated, explaining how, as a matter of principle, we blocked a hundred sites (principally porn and hate sites) through internet providers. It was only some months later that I understood the purpose and the reason for the seriousness of Ding Guangen's visit. It was to make final checks before China announced its national policy on the internet.

Imagine if, instead of opening up a parallel cyber-universe, China had out of fear of new media blocked its development. Where would China be today without Alibaba, Baidu, Tencent, Huawei, ByteDance and other infocomm technology companies which even the US is wary of today? It was a remarkably farsighted approach although not one without risk. Internally, there must have been furious debate about loss of control to external influence and manipulation. The study of little Singapore gave some assurance. Thus, at a critical juncture in China's modern history, Singapore made a small contribution. Some months later, on an official visit to China, I received an unexpected invitation from Ding Guangen to a private dinner at Zhongnanhai. It was his way of thanking Singapore.

Across a broad front, Singapore supported China's reform and opening up which the Tiananmen incident almost derailed. During the crackdown in June 1989, the Singapore government issued a statement expressing not only sorrow but also hope for the future. I had just joined the Cabinet and saw senior ministers leaving early after lunch for a meeting with Lee Kuan Yew to discuss Singapore's response. In 1990, formal diplomatic relations were established. Understanding Deng Xiaoping's determination to put China firmly back on track, Singapore supported China's early joining of APEC.

I remember vividly the first meeting that China participated in Bangkok. At an informal lunch, China's Li Lanqing, Taiwan's Vincent Siew, Hong Kong's Brian Chau and myself spontaneously decided after collecting our food from the buffet line to sit together at the same table. I felt like a relative joining a family lunch. China's membership of APEC (which necessitated careful agreement on the terms of Taiwan and Hong Kong's inclusion) could not have come about without the leadership of US President George H. W. Bush (Bush Senior). At his meeting with Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore in January 1992, Bush asked Lee to convey to China's President Yang Shangkun who was visiting Singapore a few days later his wish for improved relations with China. At his meeting with Yang, Lee also encouraged China to join GATT (later WTO) as quickly as possible. It was my privilege to have been Lee's notetaker for both meetings.

The return of Hong Kong to China on 1 July 1997 was celebrated with joy in Singapore. I was in Hong Kong with Lee Kuan Yew at a historic moment which was deeply emotional for many ethnic Chinese around the world. Singapore's English-language Straits Times carried the headline "China ends 155 years of shame". Unfortunately, the Asian financial crisis followed soon after. While Asian economies were toppling one after another, China pump-primed its economy and kept the renminbi steady. At the turn of the millennium, China's economy streaked ahead of ASEAN's. When Premier Zhu Rongji offered an FTA with ASEAN at the Leaders' Summit in November 2000, ASEAN leaders did not know how to respond because China was increasingly seen as an economic competitor. Singapore played a leading role in securing ASEAN's positive response to Zhu by insisting on an early harvest package for the other nine ASEAN countries. We saw a historic opportunity for regional stability in China's gesture of friendship and seized it. When the Framework Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Co-Operation between ASEAN and China was signed in Phnom Penh in 2002, Zhu made two remarks: one, that if the FTA resulted in an unfavorable balance to ASEAN after ten years, it should be renegotiated; second, that China would never seek for itself an exclusive position in ASEAN.

Within our diplomatic capabilities, Singapore lobbied for China's early accession to the WTO which finally took place in Doha in November 2001. The negotiations were difficult for China with the US, EU and Japan coordinating their demands. Feeling the pressure, China's trade negotiators requested Singapore not to add to their burden. Since Singapore's needs were more than adequately covered by the major powers, we agreed immediately. A few years later, Singapore, together with New Zealand, Chile and Brunei launched the Trans-Pacific Partnership. I encouraged China to become a member too. China Commerce Minister Shi Guangshen demurred, explaining that China had already paid too heavy a price for entry to the WTO and could not afford more concessions. Indeed no other developing country joined the WTO on tougher terms.

Singapore's Chinese-ness is part of our DNA, entangling Singapore with China in a way which causes complexities both domestically and in our foreign policy.

In 2008, Singapore and China concluded an FTA which went beyond the ASEAN-China FTA. Around 2011, China indicated it would not stand in the way of a free trade agreement we were negotiating with Taiwan while objecting to other countries doing the same. In 2013, Singapore and Taiwan signed an agreement with Taiwan carefully named ASTEP (Agreement between Singapore and the Separate Customs Territory of Taiwan, Penghu, Kinmen and Matsu on Economic Partnership). This was extraordinary and attested to the deep trust by China that Singapore's relationship with Taiwan would help and not hinder eventual reunification. That trust enabled Singapore to provide the venue for Xi Jinping's unprecedented meeting with Ma Ying-jeou as an equal. That equality extended to the equal sharing of the bill for dinner at Shangri-La Hotel. Xi brought Guizhou Moutai while Ma brought Kinmen Kaoliang, both equally powerful spirits.

Singapore could only play this unique role because of its Chinese-ness. Just before he became foreign minister (and without our foreknowledge of his coming promotion), I hosted Yang Jiechi as an MFA Distinguished Visitor to dinner in February 2007 where he spoke of the "mutual affection between our two peoples". I was touched. It was a sentiment I shared but could not have expressed. Singapore's Chinese-ness is part of our DNA, entangling Singapore with China in a way which causes complexities both domestically and in our foreign policy.

Singapore can never afford to have other countries in ASEAN see us as a Chinese state in Southeast Asia.

Singapore's 'Chinese-ness'

Singapore's Chinese-ness was a key reason for our separation from Malaysia. But affirming our multiracialism was fundamental to the establishment of Singapore as an independent sovereign country. The challenge of race, language and religion is never fully overcome. That is why we have to make the pledge every day. From time to time, there are heated debates over culture, education, immigration and other related issues. The key in all cases is balance. We must never take our eye off this ball. If we do, the consequences can be serious. With the growing importance of China to Singapore, we have to trim our position all the time. One foreign ambassador asked me why it was necessary for Singapore to have both a China Cultural Centre and a Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre. I replied that it was absolutely necessary to separate the two to avoid confusion. I think he was testing me.

Singapore can never afford to have other countries in ASEAN see us as a Chinese state in Southeast Asia. Lee Kuan Yew made it a matter of principle that Singapore would establish diplomatic relations with China only after our neighbours had done so. For many years, Singapore together with other non-Communist ASEAN countries worked with China to counter Vietnam's expansion into Cambodia. After Vietnam withdrew its forces from Cambodia, it sought ASEAN membership and invited Lee Kuan Yew to be an adviser. However, there was lingering suspicion of Singapore's relationship with China which took some years to dissipate. I knew the concern had largely evaporated when, one day in 2002, while reporting to Vietnam Premier Phan Van Khai on the work of our bilateral economic commission, he started giving me homework.

Yet, it is not possible for others not to see us as majority cultural Chinese in our make-up. This is not a matter of presentation but of fact which we should wear naturally. When Francis became Pope in March 2013, he established a commission of eight Catholics to recommend reform of the Vatican's administrative and financial system. For two years I did not know why I was asked to be a member. The appointment came as a surprise to me because I had not been active in my diocese. Only later did I find out that the Holy Father had asked for a Chinese Catholic to be included (all the others being European) and I was that Chinese. Someone told a Cardinal who was putting the commission together that I had left government and become available.

Had ASEAN been asked for its support by the Philippines before it took China to compulsory arbitration, I doubt we would have agreed.

However, it is paramount for Singapore's Chinese-ness to be distinguished from our status as an independent, sovereign, multiracial country. In 2013, the Philippines took China to an arbitration tribunal under UNCLOS over South China Sea claims. The Philippines invoked compulsory arbitration. As China had opted out of compulsory arbitration when it acceded to the treaty (like many big countries), it refused to participate. The tribunal (which included a judge appointed on China's behalf since China refused to appoint any) decided that China could not exclude itself and went on to construct China's case, again on China's behalf, without its participation. Not unexpectedly, the tribunal ruled against China.

Had ASEAN been asked for its support by the Philippines before it took China to compulsory arbitration, I doubt we would have agreed. But the Philippines did not need ASEAN's permission and had every sovereign right to act on its own. Singapore was put in a difficult position because many years before, Singapore had played a leading role in establishing UNCLOS and felt a certain obligation to defend its judicial process when the tribunal made its finding against China. As a small country, Singapore is very reliant on multilateral institutions for its political and economic well-being. Singapore's relationship with China was affected for a couple of years but has since recovered. At that time, many mainland Chinese were unhappy that "Chinese Singapore" did not take China's side.

Singapore's Chinese-ness is only one facet of what makes Singapore Singapore. There is an Indianness in us too. In 2010, Indian Home Minister P. Chidambaram invited me and my wife to his hometown in Chettinad for a vacation. As old friends, he wanted to acquaint me with his Chettiar heritage. During one conversation about the role Singapore played in India's development, he casually remarked that many Indians considered Singapore to be a part of India. He meant it affectionately and I appreciated the sentiment. Today, such a remark would be readily misunderstood. Notwithstanding, Singapore's relations with India are of strategic importance to our long-term well-being. Yet another facet of Singapore is our reflection of Malaysia. In the speech I gave in Kuala Lumpur at the launch of my book in 2016, I described Malaysians and Singaporeans as "one people, two countries". Tan Sri Dr Rais Yatim and Tan Sri Rafidah Aziz, both old friends and colleagues who honoured me by their presence, smiled. It is often difficult in a crowd of Malaysians and Singaporeans to distinguish between the two. This affinity naturally complicates bilateral relations, as it does too in our relations with China and India.

Although China does seek greater influence in the world, I do not believe that it wants to displace the US as top dog. It is not how China sees itself.

China's dual circulation strategy in response to US antagonism

In ten years, China's nominal GDP may overtake that of the US. Short of nuclear war between the US and China, there is little doubt that China's importance to Singapore and ASEAN will continue to grow. But we have to be watchful of the worsening relations between China and the US which is affecting the entire world. US antagonism towards China's rise will not abate for years to come. It stems from frustration with its own internal contradictions and heightened concern that China will displace it as the pre-eminent power in the world. Although China does seek greater influence in the world, I do not believe that it wants to displace the US as top dog. It is not how China sees itself. Except for a short period during the Cultural Revolution, China has never been a missionary power. It sees its civilisation and culture as unique to itself. Unlike the West, it does not proclaim its values to be universal. What China desires is a multipolar world with itself as one of the major poles. China knows that it may be years, even decades. before the US accepts a multipolar reality. China's response to the US is predictable: be firm on matters of principle, retaliate if necessary but avoid escalation where possible.

China's dual circulation economy plan elaborates this strategy. The internal circulation economy is to ensure that the Chinese economy will continue to thrive regardless of external disruption. China fully expects the US to put pressure on it from every direction over an extended period of time with the help of allies. Psychologically, Beijing is preparing the Chinese people for "protracted warfare". China already has the world's most vertically integrated economy. It is working furiously to overcome critical deficiencies like nano-chip technology. There is quiet confidence that its internal market is big enough to sustain continued growth. China already has a bigger retail market than the US.

Although the external circulation economy will still be given high emphasis, and remains a critical stimulus for domestic progress, China knows that different parts of it will be disrupted at different times by the US. Among the Five Eyes countries, there is tighter and more public coordination. The US is stepping up pressure on Europe, India and Japan to support its moves. They will go along sometimes, but not every time, and certainly not on all issues. With a secure internal circulation economy, China's domestic policy will be less of a hostage to US interference and its foreign policy will have more room for manoeuvre.

The dual circulation economy is not novel. Dynastic China always depended more on internal circulation than on external circulation. When Lord Macartney presented gifts from King George III to Emperor Qianlong in 1793, the latter gave the curt response that there was nothing China was not capable of producing for itself. This arrogance became China's undoing and the country could not withstand the Western onslaught in the subsequent decades. Internalising this lesson, China takes care to underline that it will continue to open up to the world under the dual circulation strategy. The Belt and Road Initiative is integral to the external circulation economy and, despite opposition from the US and a few other countries, remains vital for the development of critical infrastructure in Asia and Africa.

The details of this dual circulation strategy - increasingly presented as an imperative - are currently being elaborated in the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-2025) which is being drawn up. The key idea is strategic robustness which enables China to continue opening up without thereby becoming more vulnerable. A strong international circulation will help China overcome the US's stranglehold on critical technology and its weaponisation of the international financial system.

Recently, Henry Kissinger warned that US and China leaders "have to discuss the limits beyond which they will not push threats". Otherwise, "we will slide into a situation similar to World War I". Further, the US should "think of an economic world in which no other country should be able to blackmail us, but where that objective is not designed in such a way that all potential technological capabilities in other countries have to be confronted and reduced". China's dual circulation strategy is intended to help conduce to this outcome. The stark reality is that US-China relations in the coming years will have fateful consequences for all of humanity in the 21st century.

Much will depend on the US recovering its strength and self-confidence. American society has never seen such division since the Civil War. Under President Trump, US foreign policy has put America first in a forceful way including restricting foreign student access to universities which are the best in the world. The US can only be "a benign superpower", a term frequently used by Lee Kuan Yew, if it is internally united, hopeful and vital. The Covid-19 pandemic has been a testing period. The IMF estimates that the US economy will contract 4.3% while China's will expand by 1.9%.

The only issue which can undermine ASEAN-China relations is the South China Sea.

Criticality of ASEAN

The future of Singapore and ASEAN is bound up with the titanic contest between the US and China. Peace and development in ASEAN require us to balance the big forces at play, and in a dynamic not static way. Sometimes, we may have to lean further in one direction to maintain our poise. Our objective is always to be the peacemaker. Singapore's relations with China can only continue blossoming if ASEAN, as a whole, is stable and neutral. China is already ASEAN's most important trading partner and will become more so in the future. It is in ASEAN's interest to welcome the presence of other partners as well, especially the US. We welcome everyone's friendship provided no one insists on an exclusive friendship, which was Premier Zhu's wise insight into the psychology of Southeast Asia. A friendly, unthreatening ASEAN open to all the major powers is good for China.

The only issue which can undermine ASEAN-China relations is the South China Sea. Once the Code of Conduct is signed, minds can turn to win-win cooperation and joint development of mineral and maritime resources. For example, Hainan Island, which is already a special economic zone and a separate customs region, can be brought into closer relationship with ASEAN. By so doing, the South China Sea becomes (again) a peaceful waterway connecting China and Southeast Asia and one open to all countries in the world. For much of maritime Asian history, China and Southeast Asia enjoyed close relations without significant conflicts, with the trade winds bringing people, goods and ideas both ways.

ASEAN will play a modest but significant role in China's internal circulation economy and a major role in China's external circulation economy. Singapore, which is a creation of 19th century China trade, will play an essential role in China's external circulation economy. Singapore has been an enthusiastic supporter of the Belt and Road Initiative. As the renminbi becomes a major currency for international trade, Singapore's role in China's external financial circulation will assume greater significance. Hong Kong's role has been somewhat diminished by Beijing's new national security law while London's role has also been affected by increasing pressure from Washington to act against China.

Without ASEAN, Singapore's manoeuvring space is severely circumscribed. ASEAN must always be the first circle of Singapore's foreign policy. We are a small country and can never hope to treat major powers as anything but. Other ASEAN countries more or less feel the same way. It is this common fear which binds us together. Although we are not united like members of the EU, we do share common instincts which have grown stronger. The diversity within ASEAN forces us to adopt flexible internal structures and systems. This variable geometry gives ASEAN its resilience. Singapore's good relations with China are contingent on ASEAN's good relations with China. When I was trade minister, we often negotiated bilateral FTAs with major economies first before encouraging the rest of ASEAN to come along. In the case of China, we took a conscious decision that ASEAN should have its FTA with China signed up first before we negotiated with China bilaterally.

Although Singapore's relationship with China has a long history, it is right that we mark the establishment of diplomatic relations 30 years ago as a milestone. It marks two important features: one, that we are politically separate from China and, two, that we share a natural affinity borne of history and culture. Clarity of these two features will ensure that the relationship between Singapore and China will continue to flourish amidst geopolitical and geo-economic shifts, for our mutual benefit and that of the region.

Related: Singapore's ambassador to China Lui Tuck Yew: Singapore must stay relevant to China | Chinese ambassador to Singapore Hong Xiaoyong: China-Singapore ties tested and strengthened through the pandemic | Yang Jiechi's Singapore visit: Seeking strategic space | Beyond 30 years: History, places and images of Singapore-China relations | China's Five-Year Plan: A bottom-up model of policy making?