[Big read] The rise and fall of China’s independent bookstores

Built by idealists and sustained by belief, independent bookstores became places to gather and breathe in China. As the tide turns, their owners face the hardest question: how long to keep the lights on. Lianhe Zaobao journalist Zhang Guanghui speaks to academics and those in the industry to find out more.

Chinese book critic Fang Xuxiao is often teased by friends as being mad about bookstores. In a move somewhat out of step with an era dominated by e-commerce and livestream book sales, he has released a new title, Bookstore Calendar 2026 (《书店日历2026》), sold exclusively at physical bookstores. Through illustrations, conversations and other forms, the book documents independent bookstores of widely differing styles across various parts of China.

Fang has worked as a bookstore clerk and a publishing executive, and he has spent years travelling around China visiting bookstores. He told Lianhe Zaobao that he hopes this book will be something “unique to bookstores”, because independent bookstores are facing unprecedented difficulties. “If the publishing industry can offer more products like this to bookstores, then I think bookstores may find new ways to survive.”

According to official data, China’s book retail market is worth 112.9 billion RMB (US$16.2 billion), yet physical bookstores now account for only 14% of the market. The state-owned Xinhua Bookstore chain, which makes up just 1.5% of the total number of bookstores, takes more than 30% of all physical bookstore sales, while privately run independent bookstores can only struggle to survive in the narrow gaps that remain.

... the number of independent bookstores in many parts of China has continued to grow against the trend in recent years, accompanied by a wave of “owner-curated” bookstores.

The difficulty of making money from selling books has long been a shared predicament of the bookstore industry worldwide. Even so, the number of independent bookstores in many parts of China has continued to grow against the trend in recent years, accompanied by a wave of “owner-curated” bookstores.

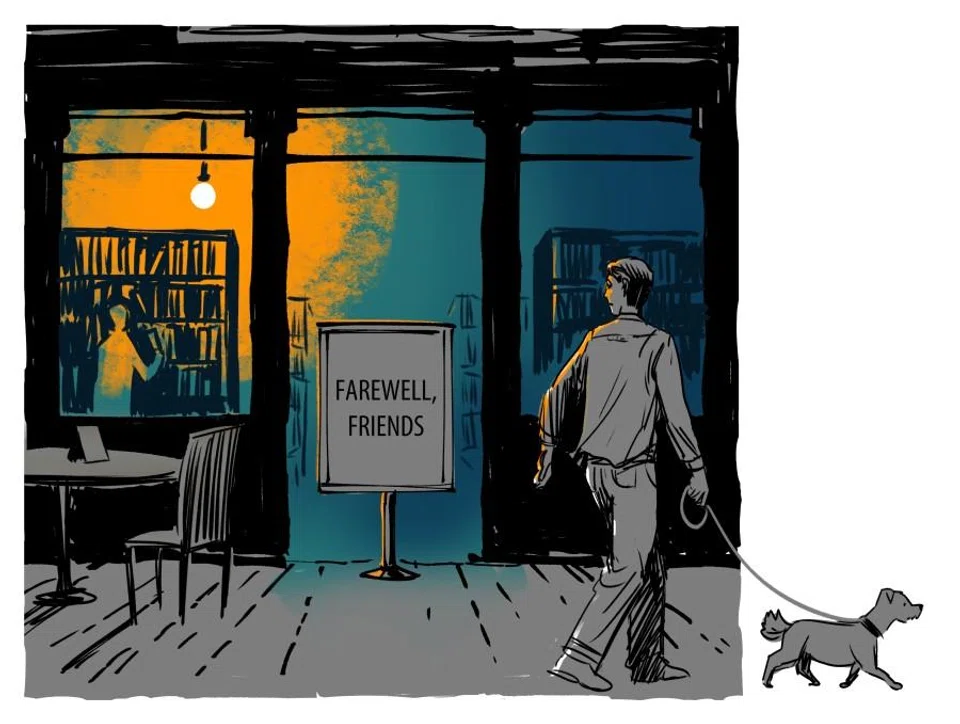

These independent bookstores, often founded around the personal interests of their owners, go beyond selling books, coffee, and cultural merchandise. Some place a greater emphasis on creating spaces for public life, organising activities and discussions on social issues. During the pandemic lockdowns in particular, they offered venues for Chinese citizens eager for face-to-face interaction, becoming spiritual landmarks of their cities. Over the past year, however, many such bookstores have once again ended up closing their doors.

Fang believes that many independent bookstore owners are typical idealists or arts-minded youths who open a shop on a whim. But rising rents, an economic slowdown, and consumer downshifting, among other factors, have all taken a toll on bookstore operations.

Distinctive personalities: independent bookstores in the ‘3.0 era’

Zhu Yan, the owner of Wild Pear Tree Bookstore in Chengdu, which closed in June last year, said in an interview that besides the worsening business environment caused by broader economic conditions, bookstore activities were also constrained by regulatory restrictions. The overall industry atmosphere had changed dramatically, leaving him with “a strong sense of disillusionment”.

In 2022, as China gradually emerged from pandemic lockdowns, Wild Pear Tree and many other independent bookstores opened in quick succession in Chengdu, the capital of Sichuan province. At the time, Zhang Feng, a current affairs commentator who lives in Chengdu, wrote on his personal WeChat public account that China’s bookstore industry was undergoing a profound transformation. “Built around small communities driven by the owner’s personal style, bookstores have entered the 3.0 era.”

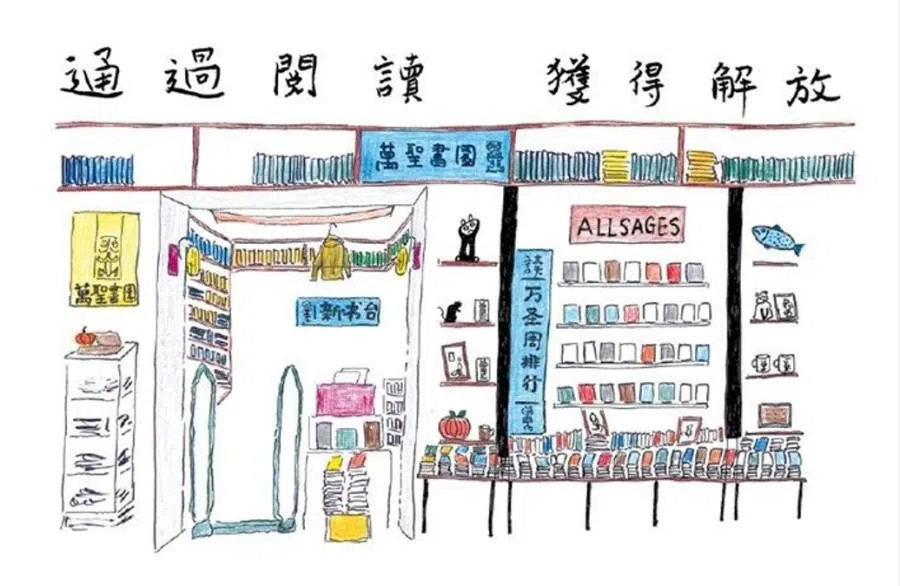

China’s privately run independent bookstores have gone through over 30 years of development. Beijing’s All Sages Bookstore and Shanghai’s JF Books, which opened in the 1990s, are considered the first generation of independent bookstores. Fang Xuxiao recalled: “Back then, there wasn’t even a concept of ‘independent bookstores’ — there were only books in the shop, nothing else.”

Chain bookstore One-Way Street, founded in the early 2000s by Chinese cultural figures such as Xu Zhiyuan, is regarded by Fang as a second-generation independent bookstore. “The term ‘independent bookstore’ really began to be used roughly starting with literary bookstores represented by One-Way Street.”

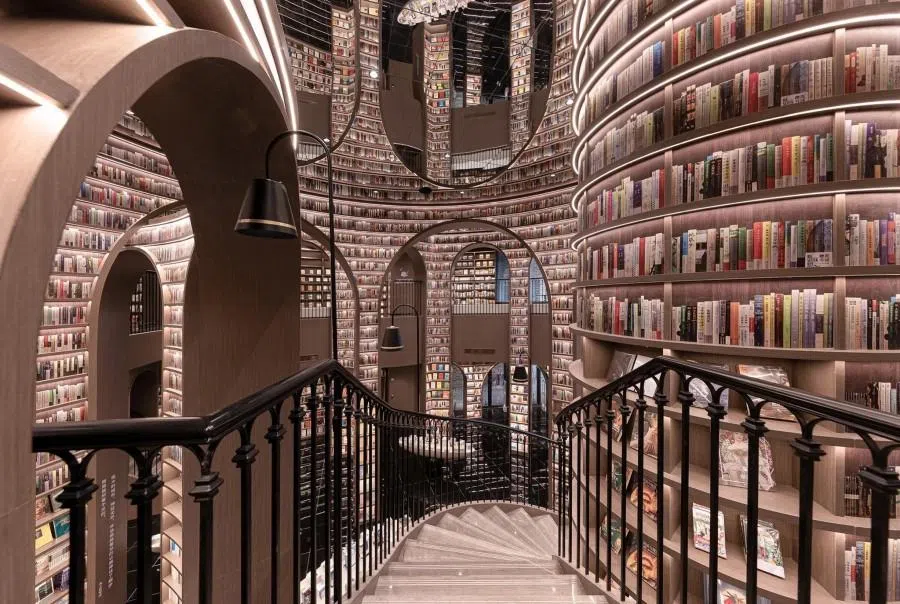

After that, chain bookstore brands such as Yanjiyou and Zhongshuge — often creating “the most beautiful bookstores” within shopping malls and becoming popular social-media check-in spots — rose with the backing of capital. Yanjiyou, which at one point had more than 50 outlets across China, suffered a cash-flow collapse during the pandemic and has now almost entirely shut down.

Around the same time as Yanjiyou’s decline, third-generation independent bookstores began to emerge prominently. Fang Xuxiao said: “Bookstores have increasingly come to be anchored in personal tastes or interests. Bookstores with a strong owner-curator or proprietor-driven character have become ever more common.”

“... independent bookstore owners are highly individualistic. They do not shy away from their aesthetic preferences, and will refuse certain books, authors, or readers entry into their space.” — Zhang Feng, a current affairs commentator who lives in Chengdu

A renaissance of sorts in second-tier cities

Wang Jun, the owner of Yi Wei Bookstore in Chengdu, told Lianhe Zaobao that bookstores today are no longer simply places to sell books, but “cultural spaces that produce and disseminate content”. “In Chengdu, there are bookstores themed around science fiction, some that lean toward literature, feminist bookstores, second-hand bookstores as well — and of course, the most common type of independent bookstore is probably in the humanities and social sciences.”

Zhang Feng once drew a contrast: “The store manager at a Yanji You bookstore is an indistinct employee-for-hire, while independent bookstore owners are highly individualistic. They do not shy away from their aesthetic preferences, and will refuse certain books, authors or readers entry into their space.”

He cited Wang as an example: “I know several bookstore owners who would feel offended if you asked them for self-help or ‘success studies’ books — they can say no, which is precisely the soul of independent bookstores.”

Since October 2019, Wang has been running Yi Wei Bookstore in Chengdu’s Yulin neighbourhood, an area full of everyday street life. This independent bookstore, themed around the humanities and social sciences, frequently hosts salons and reading groups, with discussions ranging across philosophy, history, art and anthropology, while also engaging with social issues.

Shortly after Yi Wei Bookstore opened, it ran straight into the pandemic — yet this unexpectedly became an opportunity for organising events. Wang said that from the summer of 2020 to the winter of 2022, Yi Wei Bookstore held around 100 in-person events each year, sometimes as many as two to three events a week.

Wang recalled that during the pandemic, bookstores were not categorised as regulated industries in the way restaurants and bars were, “so there was a kind of loophole”. He did not think that customers who came in at the time were especially enthusiastic about cultural activities. “During that period, people were probably more urgently hoping that there would be a physical, face-to-face space for interaction.”

In the wake of the pandemic, the vision of public life fostered by Chengdu’s independent bookstores such as Yi Wei Bookstore and Wild Pear Tree became a cultural phenomenon that attracted nationwide attention.

Zhu Yan’s Wild Pear Tree Bookstore opened in June 2022 and went on to host more than a thousand events over the next three years, before announcing its “glorious closure” last June.

In his closure notice, Zhu wrote that when the bookstore first opened, Chengdu was still under lockdown. “I still remember how people in the bookstore’s group helped one another — sharing ibuprofen and fever medicine with strangers, helping to procure food, feeding pets at people’s homes, taking in strangers stranded on the streets and unable to return home. In the midst of despair, people encouraged and supported one another.”

In the wake of the pandemic, the vision of public life fostered by Chengdu’s independent bookstores such as Yi Wei Bookstore and Wild Pear Tree became a cultural phenomenon that attracted nationwide attention. Related reports frequently appeared in Chinese media outlets whose primary readership is the middle class. In recent years, Chengdu’s authorities have also repeatedly promoted the fact that the city has more than 3,500 physical bookstores, the most in China.

“They chat every evening, talking about all kinds of topics… Chengdu, up to now, hasn’t been managed very strictly. After all, you people are just chatting, so the authorities’ degree of openness in this regard is even greater than in Beijing or Shanghai.” — Professor Xu Jilin, History Department, East China Normal University in Shanghai

Xu Jilin, a professor in the history department at East China Normal University in Shanghai, analysed this phenomenon at a public event in 2024. He noted that Chengdu has long had a teahouse culture and places great emphasis on public life, but that today young people go to bookstores instead of teahouses. “They chat every evening, talking about all kinds of topics… Chengdu, up to now, hasn’t been managed very strictly. After all, you people are just chatting, so the authorities’ degree of openness in this regard is even greater than in Beijing or Shanghai.”

Post-pandemic economic downturn makes bookstore operations more difficult

Fang Xuxiao observed that not only Chengdu, but also second-tier cities such as Chongqing and Hangzhou have in recent years developed rich independent bookstore ecosystems, ushering in a “renaissance of small bookstores”. This was because “after being trapped for three years by the pandemic, people really wanted to go out and do something”. Smaller cities have likewise seen a growing number of independent bookstores emerge, driven in part by “young people returning to their hometowns from big cities and bringing back relatively mature ideas, leading local cultural trends”.

However, this wave of independent bookstores centred on Chengdu soon encountered challenges after the pandemic. Wang Jun revealed that while Yi Wei Bookstore had more or less broken even during the pandemic, conditions worsened in 2023. “The overall economy is in decline, and the group that spends money at bookstores tends to be relatively young. Young people’s employment situation is very poor, so they cut back on this kind of non-essential consumption.”

In the second half of last year, a planning company run by Wang’s friends transformed Yi Wei Bookstore into an exhibition space and cafe. “They still hold some activities, but the proportion of books will be reduced,” he said. He noted that every bookstore has its own difficulties. “Everyone is just barely hanging on — it’s a matter of who can hold out longer.” He admitted that he has already run the bookstore into debt: “Under the original model, I’ve been making serious losses for two years. I really couldn’t hold on anymore.”

Zhu Yan likewise cited China’s macroeconomic conditions and the realities of operating costs, while also pointing to regulatory restrictions on the industry — “there’s less and less that you’re allowed to do” — as key reasons behind his decision to close the bookstore.

Industry insiders: a good era has probably come to an end

For example, an annual independent bookstore market held in Chengdu last May was abruptly cancelled on the day of the event after organisers were given last-minute notice, even though Wild Pear Tree Bookstore had already spent days preparing for it. Zhu said: “So much preparation went down the drain — it was really demoralising.”

Zhang Feng, who entered the independent bookstore scene in 2023 and became the owner of You Xing Bookstore in Chengdu, wrote a post last September detailing the successive closures of several independent bookstores in the city, including Wild Pear Tree, Changye Bookstore (长野书局), Yiniao Bookstore (弋鸟书店), and KPee.Art. He concluded that “Chengdu’s literary scene is dead” and that “a good era for Chengdu’s independent bookstores has probably come to an end”.

In a case of words turning prophetic, Zhang suddenly announced in late October last year that You Xing Bookstore would be closing due to “force majeure”. The immediate trigger was the series of lectures and talks on public issues that the bookstore had long been organising, which had drawn outside attention. At one point, there were reports locally that media coverage of the bookstore’s closure had caught the attention of the authorities. A few days later, Zhang published another post titled “Thank You, Everyone,” saying that the bookstore would be able to continue operating after all, as “everyone’s love ultimately produced some kind of miraculous effect”.

Those who open bookstores tend to be idealists to some extent, but keeping a bookstore alive is the real challenge. Many small independent bookstores in China go through repeated cycles of opening and closing, which he sees as “a very natural ecology”. — Fang Xuxiao, a Chinese book critic

Fang Xuxiao believes that the brief boom of independent bookstores in Chengdu was a normal phenomenon. Those who open bookstores tend to be idealists to some extent, but keeping a bookstore alive is the real challenge. Many small independent bookstores in China go through repeated cycles of opening and closing, which he sees as “a very natural ecology”.

He said: “No matter how many people try to dissuade others from opening bookstores — even when bookstore owners themselves come forward to say ‘don’t open a bookstore’ — there will always be people who flock to do it anyway.”

Bookstores fighting the homogenisation of cities

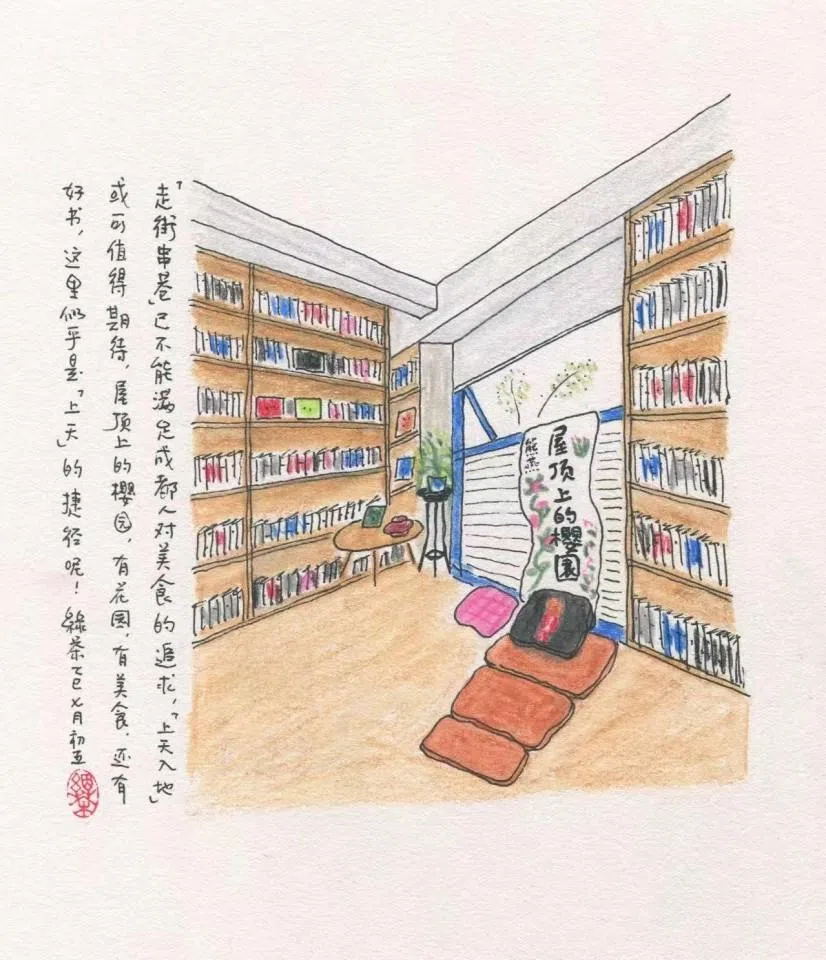

From Guangzhou’s 1200bookshop, which provides accommodation for backpackers, to Roof Cherry Garden in Chengdu, where a restaurant and bookstore are integrated into one space, Fang has spent recent years visiting bookstores across China. In a new book published at the end of last year, he documents 73 independent bookstores of different styles across the country through illustrations.

Fang said that Chinese cities are becoming increasingly dull and “more and more alike”, but highly localised bookstores of many different kinds can reveal each city’s unique character. “I have always been an idealist, hoping that every city will have a dazzling array of bookstores.”

On the other hand, Yi Wei Bookstore’s Wang Jun hopes that people will not place too much value or meaning on bookstores, nor put them on a pedestal. “The threshold for opening a bookstore today is already about the same as opening a cafe,” he said. “There are many possible carriers of public space — it does not have to be a bookstore; it could also be a gallery, museum, teahouse or bar.”

He added: “For young people today, a city that offers them a decent job and a livable environment is far more important than giving them a few good cultural spaces — it’s simply more practical.”

Chinese-run bookstores overseas aim to promote exchange and immigrant integration

One-Way Street Bookstore set up shop in Tokyo’s bustling Ginza district in early 2023. That same year, four Chinese-language bookstores opened in Tokyo.

On 28 December 2025, Tokyo’s One-Way Street Bookstore wrapped up its final event of the year, featuring a talk by Oxford University professor of social anthropology Xiang Biao on “Thinking in Chinese and International Exchange”, which drew many local Chinese residents.

Xu Zhiyuan, founder of One-Way Street Bookstore, said in a 2024 interview with Lianhe Zaobao that after the pandemic, a suitable location happened to become available in Tokyo’s Ginza district. Acting on a spur of the moment, he and his partners opened the bookstore in what he described as a somewhat blind and impulsive decision.

Xu said that at a time when global attitudes toward China have become highly abnormal, he wanted to demonstrate that many Chinese people in fact embrace globalisation, pursue pluralistic values, and wish to understand different places and societies, and that a bookstore can serve precisely as a space for intellectual exchange.

The Tokyo One-Way Street Bookstore’s curator, Xiang Leilei, also said in an interview last December that the bookstore should not become an exclusively Chinese enclave. “That’s why we organise many activities in Japanese. Chinese people living in Japan also need to integrate into Japanese society, and we want more Japanese people to understand how to interact with Chinese people. This kind of mutual understanding is extremely, extremely necessary.”

“But when you have a visible, physical space that appears here, immigrants feel more at ease — it’s like a pier emerging in a vast ocean.” — Zhang Jieping, Founder, Nowhere bookstore

Last year, another independent bookstore called Nowhere opened in Tokyo. Founded in Taipei in 2022, Nowhere was established by Zhang Jieping, who is originally from mainland China. Over the past three years, the bookstore has expanded its presence to Chiang Mai in Thailand and The Hague in the Netherlands.

Last year, Nowhere received Taiwan’s Shumei Independent Bookstore Award, a prize given by a civil organisation to encourage independent bookstores. In her award nomination video, Zhang said: “Exploring the relationship between people from elsewhere and the local community is something Enclave very much wants to do.”

She explained that in any country, when immigrants place too much emphasis on their original culture, it becomes harder for them to be accepted by locals. “But when you have a visible, physical space that appears here, immigrants feel more at ease — it’s like a pier emerging in a vast ocean. Its appeal lies in being two-way: it’s not only a place that outsiders can return to, but also a place from which locals can set off.”

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “独立书店潮来潮退 文艺复兴到此为止”.