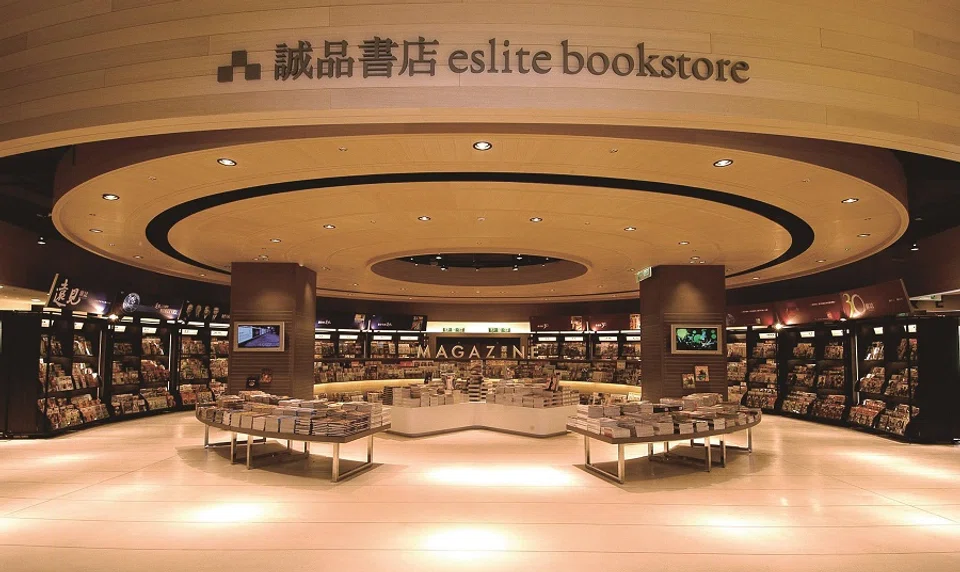

Chinese Singaporeans’ longing for Eslite bookstore and Taiwanese culture

Eslite Spectrum president Wu Min-Chieh shares her thoughts on the popularity of Eslite bookstore among Singaporeans, even though Eslite has yet to open a branch on the island.

After stopping over in Kuala Lumpur at the end of May to discuss plans to remodel our Eslite bookstore in the city, I headed to Singapore on 1 June for the annual City Reading@SG 2024 sharing session, organised by SPH Media and promoted by Lianhe Zaobao.

While 2024 marked the second iteration of City Reading@SG, its predecessor, the Singapore Book Fair, has a long history of 37 years. The ten-day event actively promotes reading and outstanding literary works, with more than 20 sessions of sharings by local and overseas authors, workshops, guided tours, book exhibitions and more.

When will Eslite come to Singapore?

Taking off from Eslite’s 35th anniversary theme and the main event, “BookStory” (《BookStory 一段由书展开的故事》), I shared how my mentality has changed in the two decades of being part of Eslite, as well as the key events that influenced my management of the bookstore.

I tackled these in chronological order, including “Turning to pride: the sudden death of my elder brother in 2009”; “Deepening belief: the passing of my father and my boss in 2017”; and “Sharpening character: the 2020 pandemic and the second curve”.

I also talked about how Eslite and myself have changed internally, before going on to how Eslite faces the external world.

The sharing was held at a large space, with the audience surrounding me on three sides. With more than a hundred faces right in front of me, I could clearly see everyone’s expressions. Among the audience were middle school classmates who I have not met in 30 years along with their families, as well as many passionate operators of bookstores of varying scales.

This was also the first time I met the editor-in-chief of the Chinese Media Group, the editor of Lianhe Zaobao, Deputy Prime Minister Heng Swee Keat and his wife Chang Hwee Nee, who is also the CEO of the National Heritage Board — all seated in the front row during the session.

... one attendee asked how bookstores can turn loss into profit (Eslite had just turned to profit in Q1 2024!). — Wu Min-Chieh, President, Eslite Spectrum

During the question and answer session, I felt for the first time the force of pressing questions from Singaporean readers.

“When will Eslite set up shop in Singapore?” A reader was quick to fire off the first question.

I replied with a smile that we were also looking forward to it, when the conditions are ripe and a suitable business partner appears.

Another reader picked up the baton: “I know you’ve already answered this, but I would still like to know when Eslite will actually come over to Singapore. What conditions should be met before Eslite comes over?”

I could not help but reply with a wide grin, which only made this reader, an elderly lady, hastily add, “What I mean is, how much funding is needed? Would X amount of Singapore dollars be sufficient? What kind of partner do you need?”

I replied that her questions made me break out in sweat, that it is not just an issue of a one-off funding, and that there are many other factors that need to be considered. She did not look at all deterred.

An array of other questions ensued: one attendee asked how bookstores can turn loss into profit (Eslite had just turned to profit in Q1 2024!). Another asked if a bookstore should continue to organise an event if the turnout is low. Others expressed how emotional they feel reading in Eslite, while some recommended going to the Songshan Cultural and Creative Park to catch a movie and browse the bookstore for a joyous outing. One person revealed that they used to work for Eslite, and had moved on to work in Singapore’s cultural industry.

As soon as the host announced that the allocated time for the sharing session would be extended, a bespectacled, middle-aged man donning a hiking vest, seated in the first row towards the left side of the stage, raised his hand and stood up to ask: “So why is it that Eslite did not set up shop in Singapore? Why did it do so in Kuala Lumpur? When did Eslite decide to go to Kuala Lumpur? Can you elaborate on the conditions that Kuala Lumpur has? Also, if Singapore had the same conditions, would Eslite come to Singapore?”

One thing is very clear: if Eslite were to come to Singapore’s shores, we must not only consider Singapore on the surface...

Everyone burst into laughter.

What should Eslite bring into Singapore?

The volley of questions made me reflect on the question of “if Eslite were to set up shop in Singapore” — this deviated entirely from the relatively simple cultural exchange I had in mind before the session.

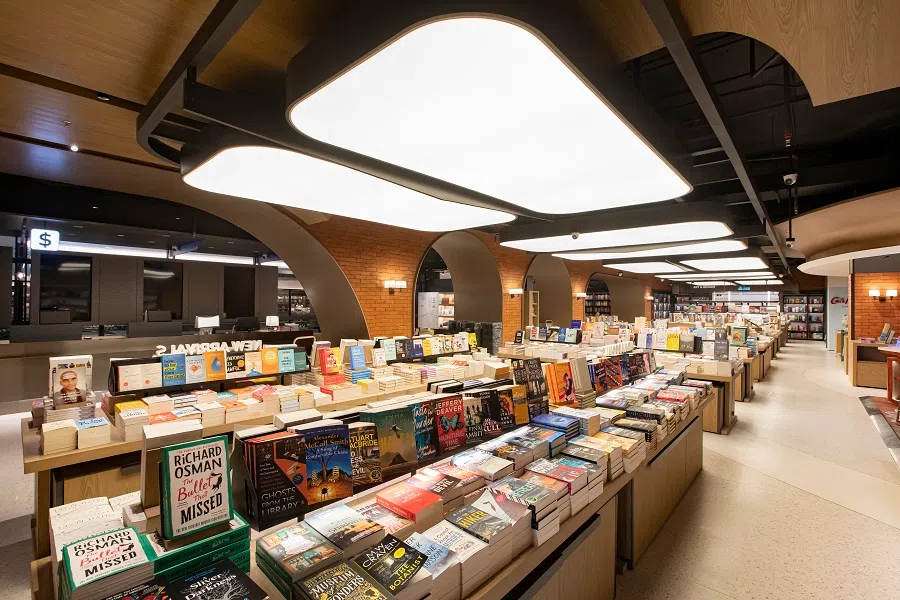

The day after the sharing, I took a stroll along the bustling Orchard Road, and with what limited time I had, I soaked in the sights and sounds of the lively commercial area and the famous bookstore I had not visited in years.

At the same time, I thought about Eslite Spectrum in Nihonbashi and Kuala Lumpur, which opened before and after the pandemic respectively. These two stores face entirely different local customs, reading habits and consumer types, be it when it comes to race, language, lifestyles and cultures or economic development stage. The way the two operate is also vastly different from how we handle our stores in Taiwan, Hong Kong and Suzhou.

One thing is very clear: if Eslite were to come to Singapore’s shores, we must not only consider Singapore on the surface; we cannot solely rely on the experience of our existing stores and bring over the products we currently offer, we must not be limited by our past operating model, and should not use that as a starting point.

Perhaps what they desire is the general cultural atmosphere of Taiwan that is behind Eslite?

What Singaporeans want from Eslite

As I looked around on my walk, I realised that in Singapore, a shopping mall is just that, a place to shop, filled with retail boutiques and restaurants to fulfil every shopper’s material needs.

When Singaporeans talk about Eslite, I feel that what they are referring to is a place flushed with content and warmth, and where their weary bodies can take a breather. What they expect is a non-utilitarian, richly spiritual, healing space, where different individuals would be well-received and accepted. They have equated such desires with Eslite.

What else should it entail then?

Inside a big bookstore in a shopping mall, I came across an interesting sign much like a “no smoking” sign — “please do not sit on the floor”. The sign depicted a person seated on the floor reading a book with a red circle surrounding it and a red, slanted strikethrough across the image — clearly showing that this was unacceptable behaviour.

I had an epiphany. To say that Singaporean readers long for Eslite does not quite hit the nail on the head. Perhaps what they desire is the general cultural atmosphere of Taiwan that is behind Eslite?

We all know that Singaporeans are well looked after by their government. As I was chatting with my taxi driver, he pointed at the roads and said that one would usually not be able to see the police — but whenever they are needed, they would appear at any moment!

Such a small, materially abundant, multiracial and multilingual country, with widespread civic awareness and enough food, shelter and clothing for all, and the sun ever present all year round coupled with the occasional rain fall and little chance of typhoons, earthquakes or tornadoes — what more do the people need?

Taiwan’s publishing industry produces 30,000 to 40,000 new titles every year, and promotional activities are happening all the time.

So how can Eslite bring “Taiwan’s Eslite” — or should I say “the social fabric of Taiwan society upon which Eslite is founded” — to Singapore? Taiwanese youths love to read and continue to frequent bookstores, a fact that never fails to impress our partners from various Japanese companies each time they visit Taiwan.

The Taiwan government gives out “culture points” to youths aged between 13 and 22. Taiwan readers would gather for a month with numbers reaching 1 million to mourn the closure of a major bookstore. Taiwan’s publishing industry produces 30,000 to 40,000 new titles every year, and promotional activities are happening all the time.

Furthermore, Taiwan is able to keep a bookstore with 100,000 titles running 24 hours at a prime location. The operators of Taiwan’s bookstores lament that they have limited space, that they are unable to accommodate enough seats, and that they can only humbly thank readers for being willing to sit on the floor to read.

Tens of thousands of people — the kind who know not to leave litter behind after a performance — would voluntarily gather at the Cloud Gate Dance Theatre, established in Taiwan in 1973, to watch dance performances. The Taiwanese know how to eat and dress, are multi-religious, are frequent travellers, advocate equal rights for LGBTIQ, and participate in democratic elections.

Taiwan has many hidden champion enterprises, and is also the centre of the world’s cutting-edge technology supply chain. However, could this be the manifestation of a certain outcome? If you want to talk about the cause, I would think the most important one is Taiwan’s folk heroes (侠 xia, an ancient Chinese warrior folk hero much like a wandering vigilante.).

It is these folk heroes who nourished the land and its people, allowing the island to maintain human warmth, chivalry (the other meaning of 侠 xia) and a sense of responsibility even as it advances towards affluence.

All thanks to Taiwan’s folk heroes

Taiwan’s “folk heroes” have yet to be dominated by politics or drowned by businesses. Many of Taiwan’s collective creations and public works do not come from the government but from the masses, arising from the volunteerism, vision and aspirations of many wonderful individuals. It is these folk heroes who nourished the land and its people, allowing the island to maintain human warmth, chivalry (the other meaning of 侠 xia) and a sense of responsibility even as it advances towards affluence.

In other words, the human warmth, chivalry, a sense of responsibility and common interest that individuals with volunteerism, vision and aspirations care about have guided society to maintain a certain extent of warmth and sense of mission. Could these be what Singaporeans are actually looking for in a shrinking Chinese reading market?

No one explains “chivalry” better than Chinese literary titan Jin Yong (the pen name of Louis Cha), with this year being the 100th anniversary of his birth. I recently finished reading two of Yang Zhao’s books on Jin Yong (《曾经江湖——金庸,为武侠小说而生的人》and《流转江湖——金庸奇侠的异想世界》; one more (《再会江湖——金庸小说的众生相》) awaits me.

I remembered the time when I read Jin Yong’s Condor Trilogy and Demi-Gods and Semi-Devils. The younger me would hide under the blankets, unable to stop flipping the pages even though I was already aware of what comes next in each page. Comparing that with the jianghu (江湖, the world at large) I have witnessed after entering the workforce, as well as the jianghu reported in the media on wars between countries or struggles between people, I more so cherish the fact that “chivalry for the country and the people” is not just a mere legend.

When recommending Yang’s three aforementioned books on Jin Yong, Comedians workshop (相声瓦舍) founder Feng Yi-kang wrote that xia is the distinction between the collective and the self — those who cheat, fight, rob and seize for the sake of their own martial arts, status, reputation and wealth are not xia.

In the chapter on “Xia and Freedom”, Yang wrote that the warrior folk heroes under Jin Yong’s pen do not see the pursuit of freedom as their life’s purpose; conversely, the most prominent aspect of these folk heroes is not the pursuit of freedom, but rather how they choose to forsake freedom.

I think that there are many folk heroes in Taiwanese society, fighting hard in various fields. They are the ones who have contributed to Taiwan’s overall cultural and social fabric.

I think that there are many folk heroes in Taiwanese society, fighting hard in various fields. They are the ones who have contributed to Taiwan’s overall cultural and social fabric. Folk heroes are less likely to exist in environments dominated by politics or overpowering business interests, making it more difficult to accommodate the disregarded or overlooked public nature of civil society.

While the emergence of folk heroes is highly idealistic, it represents an ambiguity that challenges authority and jeopardises existing institutions or vested interests at the same time. At this point, being deliberately smeared or plotted against, alongside suffering injustice and attacks, could become commonplace for folk heroes. (Today, they still have to face the online jianghu. I wonder if the online jianghu will openly and fairly conduct “Huashan sword debates” among various professions? But I am sure there will be internet armies or subordinate wings that create hidden weapons and seize the opportunity to stir up trouble.)

How did I end up here? I guess I must have felt something from my trip to Singapore, the subsequent collection of news reports on Taiwan’s energy and tech sector, as well as the books I am currently reading.

Difficult as it may be to embody the ideals of chivalry, the heart yearns for it. If one wants to practise it well, they must also strengthen their martial skills to avoid laying down one’s life.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “是诚品书店还是它依存的台湾社会?”.