China’s image moves from old-fashioned Moutai to trendy Labubu

The global rise of Labubu alongside the fall of Moutai presents an interesting perspective of Chinese society, innovating how the “China story” is told, says Lianhe Zaobao correspondent Sim Tze Wei.

Last week, members of the media in Beijing visited a soon-to-open shopping mall affiliated with a major e-commerce platform. Surprised that the journalists lingered around a display of baijiu (Chinese liquor), a staff member remarked, “The reporters seem more interested in baijiu than home appliances.”

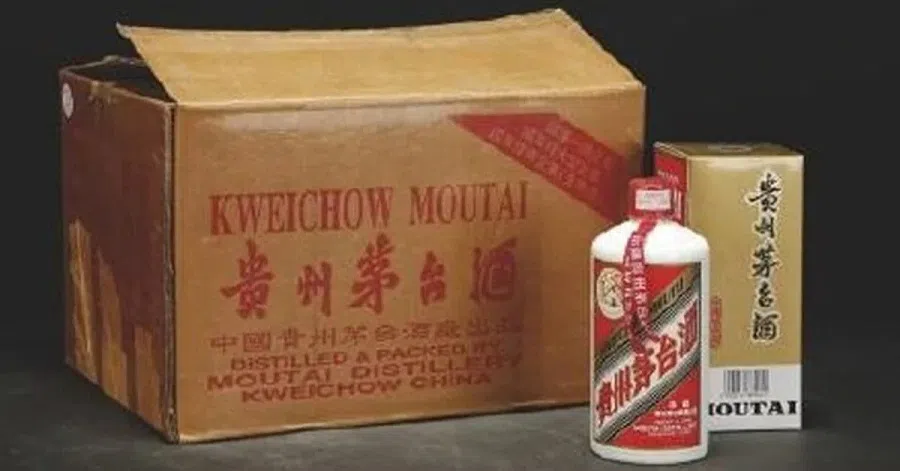

The journalists’ interest was due to the recent brouhaha over baijiu — more precisely, the intensified official anti-corruption efforts that are affecting the price of Moutai liquor.

... any gathering of three or more civil servants for a meal involving alcohol is now considered improper group dining and a sign of building cliques.

No gourmet dishes, alcohol or cigarettes

In March this year, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) Central Committee carried out a party-wide education campaign that lasted from the conclusion of the “Two Sessions” through to July, to implement the Central Committee’s eight-point decision on improving work conduct. Following that, in May, the Central Committee and the State Council revised its regulations on thrift and waste, explicitly stating that official meals cannot include gourmet dishes, cigarettes or alcohol.

Various local governments reportedly followed up. Yunnan implemented a new province-wide alcohol ban for public officials; Chongqing’s Shapingba district introduced five alcohol prohibition orders; Beijing’s Yanqing district issued a red-letter official document to enforce an alcohol ban on public employees; and Henan announced an “immediate crack down” on violations involving official dining and drinking.

There are even reports that local authorities are tightening enforcement: any gathering of three or more civil servants for a meal involving alcohol is now considered improper group dining and a sign of building cliques.

... the wholesale price for a crate of Feitian Moutai (2025 edition) dropped below 2,000 RMB (US$278) last week and is now nearing the 1,900 RMB mark.

An article titled “Is it Against the Rules for Public Officials to Dine with Colleagues After Work?” (公职人员下班后和同事聚餐,算违规违纪吗?) explained that casual meals involving up to three people are generally not an issue, but it is best to go Dutch at affordable, ordinary restaurants. The article added that one should not dine at high-end eateries, frequently meet with the same people, or form cliques.

A cadre at a state-owned enterprise (SOE) told me that during the Dragon Boat Festival, the party committee had called to ask if they had dined out and who they were with.

All this has sparked discontent. Some complained, “Might as well just order takeaway from now on,” while others sarcastically remarked, “Banning improper dining has turned into dining being deemed improper.”

Evidently, this has impacted the baijiu market. At the welcome banquet for Moutai shareholders ahead of the annual general meeting, guests were served blueberry juice instead of the iconic Feitian Moutai, signalling a bumpy road ahead for the liquor industry.

According to reference prices from the “Today’s Liquor Prices” (今日酒价) WeChat public account, the wholesale price for a crate of Feitian Moutai (2025 edition) dropped below 2,000 RMB (US$278) last week and is now nearing the 1,900 RMB mark. Dahe Daily reported that falling prices have caused massive losses for liquor resellers, prompting many to suspend purchasing. One dealer in Wuhan bluntly said, “I’ve nearly lost the equivalent of a Mercedes-Benz.”

Crackdown on alcohol-related misbehaviour

It has been over ten years since the eight-point decision was introduced in 2012. While the government’s efforts to curb the drinking culture among officials are a necessary part of its anti-corruption and clean governance drive, the stricter enforcement by local authorities may negatively impact ordinary public servants, while not affecting senior leaders and minor department heads who refuse to rein in their behaviour.

Last month, the Hainan Provincial Commission for Discipline Inspection and Supervision reported six typical cases of improper dining and acceptance of gifts and cash. Four out of the six individuals were found to have accepted or consumed Moutai, including vintage Moutai.

Zhao Hongshun, former deputy director of the State Tobacco Monopoly Administration, was reportedly found to have accepted nearly 3,000 bottles of Moutai. Wang Yong, former chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference in Yinchuan, accepted more than 30 cases of Moutai, too much even for his storage at home.

Meanwhile, at the other end of the consumer market wholly unsullied by the alcohol culture associated with officialdom, a plush toy has taken the world by storm.

A new way to tell the ‘China story’

Labubu, with its adorably ugly appearance, has sparked a global craze buoyed by celebrity endorsements. In South Korea, queues led to arguments, and the police were dispatched to maintain order, eventually forcing a halt to offline sales. In London, a fight broke out at a shopping centre over Labubu, while the tariff war could do nothing to stop the draw of Labubu in the US, where it reportedly sold out. Russians and people in the Middle East were also captivated by it. The only mint-coloured Labubu in the world fetched an astonishing 1.08 million RMB at an auction in Beijing.

Labubu is one of the core commercialised characters of Chinese trendy toy company Pop Mart. Its 38-year-old founder Wang Ning was thrust into the spotlight recently after becoming the richest person in Henan.

Labubu’s image does not have much of a Chinese flavour; it does not even have a proper Chinese name. For the uninitiated, it is hard to draw a connection to China.

However, Labubu’s image does not have much of a Chinese flavour; it does not even have a proper Chinese name. For the uninitiated, it is hard to draw a connection to China. It is in fact the creation of 53-year-old Hong Kong designer Kasing Lung, who moved to the Netherlands with his family at a young age. The mystique of Norse mythology was a major influence in his work.

Labubu’s “impure lineage” has no bearing on Chinese state media, which lavished praise on the toy — it is after all a Chinese private company that transformed Labubu into a trendy icon with global appeal.

An article from Xinhua stated that Labubu’s booming popularity can be attributed to the use of a language that the world is able to comprehend to demonstrate Chinese creativity, quality and culture. It said, “There is reason to believe that ‘Chinese creations’, which Labubu is representative of, are innovating how the ‘China story’ is told, sharing innovative opportunities with the world and allowing people from all over the globe to experience a China that is getting ‘cooler’.”

The global rise of Labubu alongside the fall of Moutai presents an interesting perspective of Chinese society.

From an economic perspective, the Labubu vogue might not be able to make up for the hit the liquor sector has taken, but it definitely has an edge when it comes to promoting China’s soft power on the global stage.

Moutai is representative of tradition and old-fashionedness. It is a luxury item symbolic of power, delineating the class differences between superiors and subordinates...

Less Chinese, more global

To some extent, Moutai is representative of tradition and old-fashionedness. It is a luxury item symbolic of power, delineating the class differences between superiors and subordinates at the table during a business meal, carrying along with it an array of implicit rules.

Meanwhile, Labubu is the opposite. It is a light-hearted stress reliever that is personalised and does not conform to aesthetic norms. It does not come with any historical baggage, and more importantly, is devoid of any groupthink. In truth, the toy is less Chinese and more global in nature.

Labubu’s meteoric rise makes one feel as if China is deviating from its past image. Meanwhile, the cold treatment for Moutai due to the alcohol ban and the restrictions on public officials dining in groups of three or more is once more a reflection of the heightened enforcement of central policy directives at the various levels, which is a chronic issue in China’s state and social governance.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “禁酒令下茅台遇冷与Labubu爆火”.