Chinese language: The 'one language, two systems' road ahead

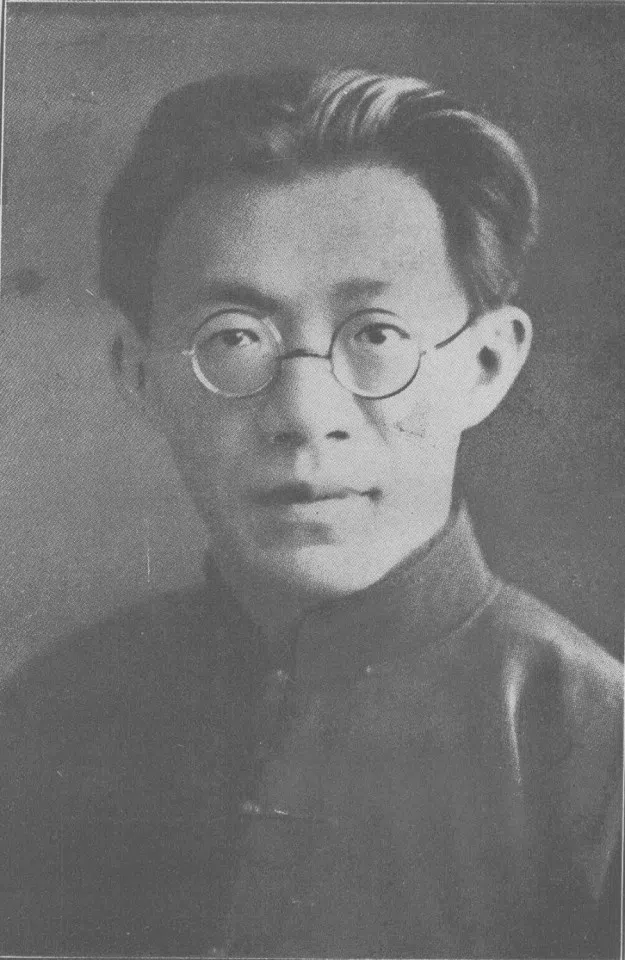

Given its pluralistic nature, the Chinese language has taken many shapes over the course of history, with its written form and the associated dialects dictated by time and place. Meanwhile, the rise of China and its growing national power have led to the emergence of Chinese as an international language that transcends national borders. Eddie Kuo, Emeritus Professor at NTU, delves into the evolution of the language in the different Chinese-speaking regions.

This year marks the 30th anniversary of the Wang-Koo talks. The media has reported extensively on this and recalled the signing of four transactional agreements on 29 April 1993 by two widely respected men - Wang Daohan, president of the Association for Relations Across the Taiwan Straits (ARATS) representing mainland China, and Koo Chen-fu, chairman of the Straits Exchange Foundation (SEF) representing Taiwan - after three days of intensive consultation in Singapore.

Politics of language

The signing of these documents - the Agreement on the Use and Verification of Certificates of Authentication Across the Taiwan Straits, the Agreement on Matters Concerning Inquiry and Compensation for [Lost] Registered Mail Across the Taiwan Strait, the Agreement on the System for Contacts and Meetings between SEF and ARATS, and the Joint Agreement of the Wang-Koo Talks - marked the thawing and development of cross-strait relations.

Among the four documents, the Joint Agreement of the Wang-Koo Talks is the most concise, but also the most important. In particular, I noticed the following clause therein: "This joint agreement enters into force thirty days from the date of its signing by both parties. Four copies of this joint agreement were signed on the twenty-ninth day of April, and the two parties will each hold two copies."

The phrase "Four copies of this joint agreement were signed... and the two parties will each hold two copies (一式四份,双方各执两份)" caught my attention. The text of the agreement was written separately in simplified Chinese characters and traditional Chinese characters (known in Taiwan as 正体字 zhengtizi, literally "standard-form characters"), with the former laid out horizontally and the latter vertically.

Both parties had apparently taken great pains over the format and content of the text, just to claim the status of the "orthodox" for their own side.

The original text only specified the date as 29 April without the year, and the two parties each held a simplified character version and a traditional character version of the agreement. After carefully signing and exchanging the documents, they each added the year separately: "1993" for mainland China's simplified character version, and "The 82nd Year of the Republican Period" for Taiwan's standard-form version.

Both parties had apparently taken great pains over the format and content of the text, just to claim the status of the "orthodox" for their own side. This was the Chinese traditional dictum of "the one thing needed is the correction of terms (必也正名乎)" being put into practice, which they thought was necessary to pursue. Furthermore, the position of "mutual non-denial" at the time was also evident. What was at play was not only the language of politics, but also the politics of language.

Binary structure of writing

Historically, due to the differing political systems and views across the Taiwan Strait, a binary structure was formed in written and spoken Chinese in the ethnic Chinese world since 1949. This article is based on observations on written and spoken Chinese commonly used in mainland China, Taiwan and Hong Kong, as well as Singapore and Malaysia, and will elaborate on the form of its binary structure through three main points.

According to analyses by historians, the fact that Chinese culture has managed to sustain itself for over 2,000 years since Qin Shi Huang's unified empire, is predominantly due to Chief Minister Li Si's unification of the Chinese writing system in the 3rd century BCE. Li's efforts served to maintain the unity of Chinese orthography despite the divergence of pronunciations across different geographical parts.

While it may be an overestimation, the half-century-long dispute between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait over the simplified/traditional divide (there being two writing systems for the same Chinese language) may be considered one of the few disagreements (or even the only disagreement) over a writing system of a political nature in all of the 2,000-year history up to now. It is worthwhile to observe whether the long-divided will come back together again someday.

Since ancient times, pundits have always taken the grand unity of Chinese people for granted. But, as a matter of fact, different degrees of divergence continue to exist within the framework of this grand unity.

Take the common language of the Chinese communities for instance. It is known as Putonghua in mainland China, Guoyu ("national language") in Taiwan, officially Huayu (Mandarin) in Singapore and Malaysia, and Hanyu to international academics. Nonetheless, despite the differences in the nomenclature, commonalities are present.

In fact, the writing system of Chinese characters has evolved through many years without causing major political disputes.

In terms of modern Chinese, it should be noted that the traditional form of writing had long been in general use before 1949, with no distinction of "traditional" or "standard-form" characters. Hence, proposals to simplify Chinese characters were only put forth after the May Fourth Movement.

In fact, in the early years after 1949, Taiwan did not reject the simplification of characters.

As early as 1936, the Nationalist government in Nanjing published the First List of Simplified Characters, the first official attempt at a Chinese character simplification campaign. In fact, in the early years after 1949, Taiwan did not reject the simplification of characters. In March 1954, Luo Jialun, vice-president of the Examination Yuan and a May Fourth Movement veteran, published a long article in Taiwan's Central Daily News entitled "The Promotion of Simplified Chinese Characters is Necessary", which was later reprinted as a standalone publication entitled The Simplified Chinese Characters Campaign.

In June 1969, the Taiwanese authorities even put forth a proposal for organising simplified characters (《整理简笔字案》). However, by the 1960s, mainland China was already officially launching its own simplified Chinese characters programme. Taiwan began to insist on upholding the position of traditional Chinese culture, claiming "orthodoxy" for itself and promoting "standard-form characters".

Simplified Chinese characters were then seen as a heresy on that side of the Taiwan Strait. Thus began the contention informed by the pan-politicalisation of the Chinese language.

Apart from mainland China, this writing system was eventually adopted by Singapore, Malaysia and the United Nations (UN).

Coexisting and mutually compatible

After 1949, the mainland set up the Committee for Language Reform of China (CLRC) to promote the use of simplified characters. In 1956, the Resolution Regarding the Promulgation of the "Chinese Character Simplification Scheme" was passed by the State Council. With the publication of the General Tables of Simplified Characters by the CLRC in May 1964, the system of simplified Chinese characters became the national standard for written Chinese. Apart from mainland China, this writing system was eventually adopted by Singapore, Malaysia and the United Nations (UN).

Traditional Chinese characters remained in common use in Hong Kong and Macau till today. In addition, some overseas Chinese schools continue to use teaching materials of Taiwanese origin written in standard-form characters. As habitual usages, cultural identities and ideologies differ among mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, there are still ongoing disputes between the supporters of simplified characters and the traditional character camp. Even within the general disagreement, there are varying opinions on each of the vying sides.

On the Taiwanese side, there has been some advocacy of a dual approach, whereby one should be able to both read standard-form characters and write in simplified characters. Coincidentally, there were also attempts in mainland China to put forward the idea of "reading traditional and using simplified", as its proponents believed that the two sets of Chinese characters could coexist and be mutually compatible.

Over the years, in the meetings of the National People's Congress (NPC) and the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), some NPC deputies and CPPCC committee members have, from time to time, put forth proposals to review the simplified Chinese characters or even to reinstate the traditional ones. Such proposals attract attention and have been openly debated, but there have not been any apparent prospects for material results so far.

In any case, in praxis, both sides of the divide are known to have taken appropriate measures out of pragmatic considerations. When mainland China and Taiwan engaged in propaganda (e.g., air-dropping of leaflets) in the 1950s and 1960s, they each made use of the script (simplified or traditional) familiar to the other side for the sake of effectiveness.

Evidently, the disagreement over the writing systems was temporarily put aside; and in accepting "one language, two scripts", there was mutual recognition.

After the establishment of the "three direct links" across the Taiwan Strait in the 1990s, it was natural for each side to maintain this approach to receive tourists from the other side. Another obvious example of such accommodation was, as mentioned above, how four copies of the document of the Wang-Koo talks were prepared, two for each party. Evidently, the disagreement over the writing systems was temporarily put aside; and in accepting "one language, two scripts", there was mutual recognition.

Binary structure of phonetic notation

There is more to the divergence of contemporary Chinese scripts than just the dispute over simplified and traditional characters. There is also the dichotomy between hanyu pinyin, which is used throughout the mainland, and zhuyin fuhao, which has a long history and is commonly used in Taiwan.

As early as 1928, the Nationalist government in Nanjing announced the use of phonetic symbols based on the Chinese character strokes. This was implemented for a long time in primary and middle schools nationwide, as well as in overseas schools. After the Nationalist government's move to Taiwan in 1949, zhuyin fuhao continued to be used alongside the national language.

In the mainland, after the founding of the People's Republic of China (PRC), the Hanyu Pinyin Scheme - using a system of romanisation for standard Mandarin - was promulgated in 1958 and implemented uniformly on that side of the Taiwan Strait. After the PRC joined the UN, this system, just like the simplified characters, became the standard for use in the UN where the Chinese language is concerned. Singapore, Malaysia and some other parts of the world also came to replace the zhuyin system with hanyu pinyin as the standard phonetic notational system for Chinese language education.

The contrast between the two systems is clear. Hanyu pinyin uses the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet to indicate pronunciation. It is thus in line with the internationally common mode of phonetic transliteration. On the other hand, zhuyin fuhao, which Taiwan sticks to, has its origin in the Chinese characters system. It is thus at odds with the internationally common mode of transliteration, which is based on Latin letters. Hence, hanyu pinyin has been far better accepted internationally than zhuyin fuhao.

Between the 1950s and 1970s, mainland China was relatively closed off from the outside world as it went through a series of political movements, including the Anti-Rightist Campaign and the Cultural Revolution. During this period, Taiwan was promoting Chinese language education abroad, with textbooks that made use of standard-form characters and zhuyin fuhao. At the same time, Taiwan offered international students opportunities to study in Chinese, using the same systems of orthography and phonetic notation. Taiwan was thus an important international centre for Chinese language learning.

Notably, due to special historical reasons, the simplified characters and hanyu pinyin used throughout mainland China were adopted for a time for Chinese classes when the Nanyang University of Singapore admitted students from the Soviet Union.

The general trend of the growing importance of simplified Chinese characters and hanyu pinyin would seem irreversible.

Moving away from coexistence

In the US and Canada, Chinese schools founded by early Taiwanese students and overseas Chinese communal organisations had also been relying on textbooks put together by Taiwan's Overseas Community Affairs Council. They taught zhuyin fuhao and standard-form characters.

However, since the opening up of mainland China, the number of students and new immigrants going overseas from the PRC has increased dramatically over the last three decades or so. Naturally, simplified characters and hanyu pinyin came into use in the newly established Chinese schools in the US and Canada.

The dual state of affairs, in which both the simplified and the traditional characters (as well as hanyu pinyin and zhuyin fuhao) are functioning side by side, has extended far abroad. Now, given the lower number of students and immigrants from Taiwan, the scale is tipping the other way.

The longstanding trends say it all - the influence of mainland China is growing by the day while Chinese is recognised by the UN as an official language for international use. It is bound to be difficult for the coexistence or binary situation to go on for much longer. The general trend of the growing importance of simplified Chinese characters and hanyu pinyin would seem irreversible.

Divergence of dialects

The linguistic plurality associated with Chinese is most evident in the divergence of dialects. This is especially true in the southern parts of China, where a variety of dialects have long existed because of geographical barriers, so much so that "pronunciations vary over the physical distance of just a hundred li (百里不同音)".

Even so, it is generally believed that no matter how different the dialects of China are, the fact that they are all written in the same script means that diversity poses no hindrance to China's unity and the national identity of its people.

There is a longstanding disagreement among Chinese linguists over the division of Chinese dialects. There are said to be seven, eight or even ten major dialects, with no final word on the matter. In fact, regardless of which scheme of division is adopted, even fellow speakers of any major dialect sometimes sound unintelligible to one another. The Chinese dialects can be divided into many sub-dialects, which in turn, can be further divided into several dialect points.

In linguistic taxonomy, the Hokkien commonly spoken in Singapore is Minnan as spoken in Zhangzhou, Quanzhou and Xiamen.

The seven major Chinese dialects as commonly designated are: the northern dialect (北方方言), Wu (吴方言), Gan (赣方言), Xiang (湘方言), Min (闽方言), Yue (Cantonese, 粤方言) and Hakka (客家方言). Among these, the Min dialect is the most divided as it encompasses five linguistically independent sub-dialects - namely, Minbei, Minnan, Mindong (Fuzhou or Foochow), Minzhong and Puxian.

In linguistic taxonomy, the Hokkien commonly spoken in Singapore is Minnan as spoken in Zhangzhou, Quanzhou and Xiamen. Among what are commonly known in Singapore as the "six major dialects" (Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, Hainanese and Foochow), apart from Hokkien itself, Teochew and Hainanese also fall under the rubric of Minnan in linguistic classification.

In spite of this, Singapore's dialect communities have developed their own distinctive cultures and identities over a long period of time, and so, in view of the sociological significance, Teochew, Hainanese and Hokkien cannot be lumped together.

Lingua franca among different Chinese clans in Singapore

For more than 200 years, Singapore has been a migrant society with multiple ethnic groups and dialect communities living together. Linguistic diversity is particularly pronounced here. According to records from 1990, there are as many as 36 English-spelt versions (usually based on dialect pronunciations) of the Chinese surname 郭 in Singapore - and this is not even counting "Guo", the romanised form officially used by China!

In Singapore, the coexistence of multiple dialects had led to the separation and even antagonism between the dialect groups. It also had an impact on the effectiveness of education, especially the national policy of bilingual education structured around English and Mandarin. In 1979, the Speak Mandarin Campaign was launched under the direction of Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew. It encouraged people to "speak more Mandarin and less dialect". Since then, the campaign has gone on tirelessly for 44 years, promoting Mandarin on one hand, and effectively diminishing the status and functions of dialects on the other.

According to the Singapore Census of Population, 76.2% of the local Chinese households spoke a dialect as their primary household language in 1980. This figure had gone down to 11.8% by 2020. On the flip side, the percentage of households where Mandarin was the primary language increased from 13.1% in 1980 to 40.2% in 2020. Over the 40 years, the figure for English grew the fastest, rising from 10.2% to 47.6%.

During the launch of the Speak Mandarin Campaign in 1979, Lee Kuan Yew had warned, "If we continue to use dialects, then English will tend to become the common language between Chinese of different dialect groups." Regrettably, even though the campaign is successful in achieving the goal of "speaking less dialect", English still looks set to become the lingua franca of the Chinese community in Singapore.

The symposium merely reflected an interest in dialect cultures, and I fear that the dialects themselves are at the end of their tether in Singapore.

Over the years, the decline of dialects has caused concern among many people. Some pertinent organisations in Singapore (especially clan associations) frequently organise events for the preservation of the dialects and their cultures, such as the spectacular Hokkien and Teochew Cultural Festivals. Notably, the Singapore Amoy Association formed a Hokkien Toastmasters Club at the end of 2020 to promote the learning of Hokkien. Equally well-received are the Cantonese and Teochew Toastmasters Clubs also organised by their respective clan associations.

In conjunction with its 85th anniversary, the Amoy Association held an international symposium on "Hokkien Culture in Singapore" in June this year. More than 500 people turned up for the academic discussions, whereby ten speakers discussed Minnan (Hokkien) culture in Singapore from the different angles of folklore, education, language, music, traditional opera, gastronomy and so on.

Evidently, the dialect cultures centred on the various clan associations still have considerable vitality of their own. However, it is striking that not a single speaker delivered their speech in Hokkien. The symposium merely reflected an interest in dialect cultures, and I fear that the dialects themselves are at the end of their tether in Singapore.

The phenomenon of the deprivation of dialects is now occurring in some of China's major cities.

Biliteracy and trilingualism

What's happening on a small scale here offers a glimpse into what's happening on the larger scale. The twofold trend of the prevalence of Putonghua and the decline of dialects is also unfolding in mainland China.

After the founding of the PRC, linguistic unification was the focus of language reform in China. It was hoped that linguistic unification could help to promote national education, reduce illiteracy, bring about cultural unity, coalesce national identity, and raise the people's level of knowledge and culture.

But dialects serve an irreplaceable function as the roots of local cultures and traditions. The phenomenon of the deprivation of dialects is now occurring in some of China's major cities. Young people speak Putonghua in school, but they are unable to fluently speak the vernacular languages of their respective places of origin (dialects) once they are back home. This trend is raising concerns.

In different regions, there are struggles between the drive to promote Putonghua and efforts to preserve dialects. For example, people are called to "defend Cantonese" (捍卫粤语) and "protect Shanghainese" (保护上海话). Ideally, to ameliorate the crisis of the disappearance of dialects, Putonghua and the dialects would coexist, rather than play a zero-sum game where the two stand as bitter rivals that can spare no place for each other.

As the future unfolds, will it be possible to preserve dialects while still promoting Putonghua? That is an issue worth paying attention to.

Such language policy of multilingualism can be seen as an embodiment of the principle of "one country, two systems".

Hong Kong today represents a rather special case. As a special administrative region (SAR), Hong Kong has set Chinese and English as its official languages, with both equal in status. At the same time, the SAR follows a language policy of "biliteracy and trilingualism".

Biliteracy means Chinese and English are used in writing, while trilingualism means there are three spoken languages: Cantonese, English and Putonghua. In Hong Kong, traditional Chinese characters are traditionally used (albeit not legally required), while English and Cantonese are used in tandem in schools. Such language policy of multilingualism can be seen as an embodiment of the principle of "one country, two systems".

On-site translation in all three spoken languages is currently provided at Legislative Council meetings and government press conferences. For government documents and webpages, simplified character versions of texts are often provided in addition to the customary traditional character versions.

With the close interaction between Hong Kong and the mainland, official correspondence is becoming more and more frequent, as are contacts between newly arrived migrants and local Hongkongers, making it necessary to maintain multilingualism.

In the long run, will the future trend be towards integration or continued pluralism? Will there be adjustments to some forms of language use despite the promise of "no change for 50 years"? For example, will traditional characters be replaced by the simplified ones and will the schools begin to teach in Putonghua? How will Hong Kong's language policy be transformed and how will the changes be executed? What will the effects be and how will the people respond? These are all matters that warrant long-term attention and studies.

Renaming Minnan as Taiwanese

The situation in Taiwan is even more peculiar. Originally, Minnan (Hoklo) and Hakka were the main languages spoken in Taiwan. In the early days, the Nationalist government made every effort to suppress them and to promote the national language (Guoyu) as the common language, resulting in the crisis of the decline of the local dialects.

However, in the past 20 years, Taiwan has politically pivoted towards localisation and begun to work hard at "saving the Taiwanese language urgently". Minnan was renamed "Taiwanese" in emphasis of its "Taiwan-ness".

The underlying aim is possibly to rid Taiwan of the Chinese language. That would be the politicisation of language taken to the extreme, making Taiwanese and English weapons for de-sinicisation.

A "Blueprint for Developing Taiwan into a Bilingual Nation by 2030" has even been put forth in recent years. The idea is to go all out to implement English language teaching and set English as the second language. The purpose of doing so is to "cultivate the people's competence in the English language substantially", so as to enhance international competitiveness.

The proposal itself is extremely controversial as it is lacking in legitimacy and feasibility, but the ruling party is committed towards it. The underlying aim is possibly to rid Taiwan of the Chinese language. That would be the politicisation of language taken to the extreme, making Taiwanese and English weapons for de-sinicisation.

For more than 70 years, due to the political separation between mainland China and Taiwan, there has been a duality of binary structures in written Chinese. Not only do traditional and simplified Chinese characters coexist, but both hanyu pinyin and zhuyin fuhao are in use. The language schism is deepened by the prolonged split between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait. And yet, amid all the commonalities and differences, each side has developed distinctive vocabularies and linguistic characteristics of its own, greatly enriching the diversity of the Chinese language.

The internet fostering pluralistic interactions

Meanwhile, due to the wave of globalisation, China is no stranger to massive population movements, including both internal and international migrations. In the international movements of people, the flux of emigrants as well as sojourners for education has reached an unprecedented scale.

Over the past 30 years, the rise of China and its growing national power have led to the emergence of Chinese as an international language that transcends national borders. Within the Greater Chinese cultural sphere, apart from mainland China, Hong Kong, Macau and Taiwan, there are numerous ethnic Chinese as well as non-Chinese users of this language in Singapore, Malaysia and across different continents.

Another important factor for us to note is the ubiquity of the internet, which facilitates exchanges and mutual influences on various fronts. The variations in Chinese pronunciation and vocabulary across different parts of the world do not affect communication. Pluralistic interactions are already the order of the day as an inevitable result of the zeitgeist.

With Chinese as an international language, varieties of its contents and usage exist, develop and change concurrently in China and elsewhere. The contents have already taken on such diversity in the linguistic sense that Chinese is veritably a lively language active in its user community.

The 21st century trend towards pluralism in the Chinese language has profound implications for politics, culture and identities. They warrant in-depth study and discussion. Will the binary (or even a more pluralistic) situation of coexistence continue to be the case for the Chinese language in the future? Or will there be convergence towards unity? This is not only a linguistic issue, but also a political and cultural one.

This article was first published in Yazhou Zhoukan as "中文一字兩制繁簡並存注音拼音互通".

Related: Prof Eddie Kuo: Singapore's ethnic Chinese have never been a unified collective | Is Chinese language alive or dying in Indonesia? | Does Singapore still want to play an active role in the Chinese-speaking world? | Taiwan's language programme imparting 'Taiwanese national identity' to US students