Politics on a plate: How Taiwan’s presidential banquets mirror a shifting identity

How does Yangzhou fried rice, shrimp rice and pearl milk tea showcase Taiwan’s local consciousness? Lianhe Zaobao correspondent Sim Tze Wei delves into the evolution of the choice of fare at Taiwan’s presidential banquets and how it reflects the island’s identity.

After nearly 20 years, I revisited southern Taiwan’s tourist hotspots such as Kaohsiung’s Liuhe Night Market and Tainan Confucius Temple, and noticed that mainland Chinese tourists have become a rare sight. Instead, visitors from Japan, South Korea, Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia have taken over.

As I stood at the dismounting stele outside the Tainan Confucius Temple, this familiar spot presented two starkly different scenes that spanned a yawning 16-year gap.

Sixteen years ago, after Kuomintang (KMT) President Ma Ying-jeou came to power, mainland Chinese tourists were allowed to visit Taiwan. Back then, it would not have taken much time or effort to spot mainland tour groups. Sixteen years on, a group of three or four mainland Chinese youths travelling together, chatting in their distinct mainland accents, have become a rare sighting. A local woman working at a cultural and creative shop in Tainan noted that, since restrictions on mainland Chinese tourists visiting Taiwan have not been lifted, these young visitors likely entered Taiwan via a third country or region.

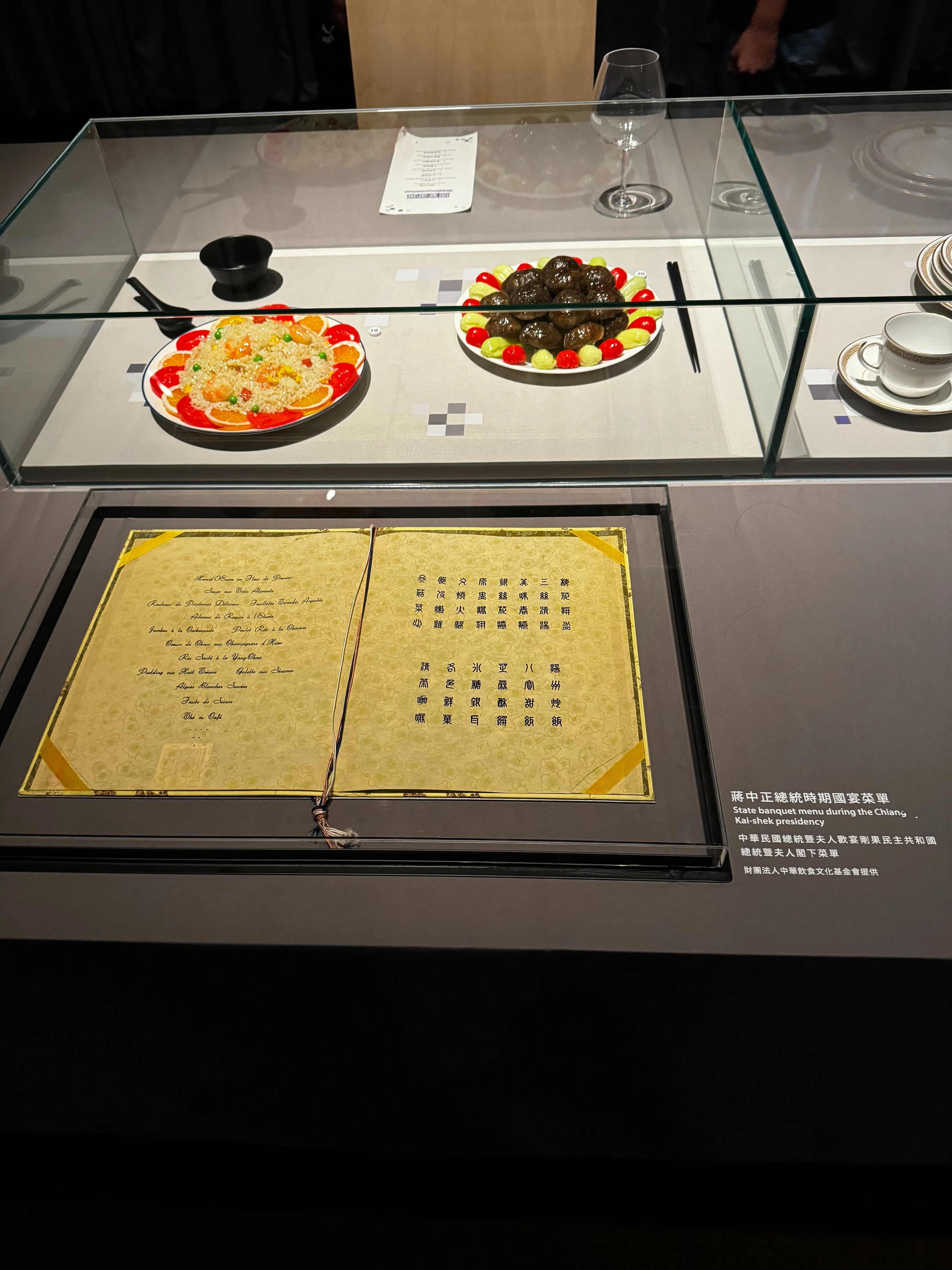

During the era of the two Chiangs — Chiang Kai-shek and his son Chiang Ching-kuo — presidential banquet dishes highlighted traditional Chinese culinary culture, mainly featuring Huaiyang cuisine; the humble Yangzhou fried rice even found its spot on the menu.

From humble fried rice to pearl milk teas

The 76-year separation between the two sides of the Taiwan Strait has seen many shifts, marked by significant phases such as Chiang Kai-shek’s policy that “gentlemen and bandits cannot coexist”, the alternation of power between the KMT and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), Ma Ying-jeou’s opening up to mainland students and tourists, and the growing rise of Taiwanese local consciousness. These historical currents are artfully reflected in a new exhibition on Taiwan’s culinary culture.

The Bytes to Remember: Taiwan’s Culinary Memories exhibition at the National Museum of Taiwan History in the suburbs of Tainan highlights the evolution of the fare served at Taiwan’s presidential banquets, reflecting the shift in Taiwan’s internal political landscape and diplomatic image as it transitioned from authoritarianism to democracy.

During the era of the two Chiangs — Chiang Kai-shek and his son Chiang Ching-kuo — presidential banquet dishes highlighted traditional Chinese culinary culture, mainly featuring Huaiyang cuisine; the humble Yangzhou fried rice even found its spot on the menu. The exhibition guide explained that the inclusion of the fried rice — with the mainland city Yangzhou in its namesake — was closely linked to Chiang Kai-shek’s ancestral roots in Fenghua, Zhejiang.

In the Lee Teng-hui era, Taiwanese local consciousness had not yet intensified, and mainland-influenced dishes such as General Tso’s chicken stayed on the menu. This dish was created by Peng Chang-kuei, a master of Hunan cuisine who retreated to Taiwan with the KMT, and Peng named it after the Hunanese military leader Zuo Zongtang.

Ma Ying-jeou continued the localisation trend by incorporating ingredients from various Taiwanese agricultural and fishery specialties, while Tsai Ing-wen took it a step further by including the ingredients’ production and retail information.

Following the first change in the ruling party, Chen Shui-bian placed an emphasis on localisation, introducing Taiwanese snacks such as Tainan rice cake and milkfish ball soup to the presidential banquet table. Ma Ying-jeou continued the localisation trend by incorporating ingredients from various Taiwanese agricultural and fishery specialties, while Tsai Ing-wen took it a step further by including the ingredients’ production and retail information.

The fare for banquets hosted by Lai Ching-te was not part of the exhibition, but according to public information, he specifically chose shrimp rice and pearl milk tea — featuring stir-fried shrimp with Taiwanese rice paired with a hand-crafted beverage from a Tainan brand.

From Chiang Kai-shek’s Yangzhou fried rice to Lai’s shrimp rice, the evolution of dish names and their significance mirrors the changing selections at presidential banquets — revealing the KMT’s early desire to present itself as the legitimate representative of China and the DPP’s later focus on asserting a distinct Taiwanese local identity.

China’s soft influence

This evolution is also evident across various facets of Taiwanese society, including the “de-sinicisation” of school curricula. History is increasingly taught from the perspective of “Taiwan’s place in the world”, rather than as a continuation of the KMT, the Qing dynasty, or earlier regimes. This shift emphasises Taiwan’s global connections dating back to the Age of Exploration, while downplaying traditional narratives such as Zheng Chenggong’s defeat of Dutch colonists and his subsequent rule over Taiwan.

Since Taiwan’s first direct presidential election in 1996, the DPP has held power for a total of 17 years under Chen Shui-bian, Tsai Ing-wen and Lai Ching-te — surpassing the KMT’s combined 12 years under Lee Teng-hui and Ma Ying-jeou. However, despite the Green camp’s longstanding efforts to promote “de-sinicisation” through policy and messaging, it has failed to block the mainland’s “soft influence” on Taiwanese life and entertainment.

Mainland dishes such as sauerkraut fish and luosifen (螺蛳粉, lit. river snail rice noodles) have also made their way onto Taipei streets.

After spending a week in Taiwan, it is clear that the island, like any other Chinese-speaking societies, has been quietly influenced by the mainland in everyday life — from food and vocabulary to TV, films and mobile applications.

In a Kaohsiung department store, I was surprised to find a popular mainland snack, Konjac Shuang (魔芋爽), which has reportedly become a hit in Taiwanese schools — especially among elementary school students. Mainland dishes such as sauerkraut fish and luosifen (螺蛳粉, lit. river snail rice noodles) have also made their way onto Taipei streets. A Taiwanese friend noted that when dining at a restaurant known for Zhejiang cuisine, customers in their 20s were actually hankering for sauerkraut fish.

My friend believes that Taiwanese youths below the age of 40 are very receptive to mainland China’s soft power, and compared with the older generation, are less wary of Beijing’s united front tactics. They frequently use platforms such as TikTok and RedNote, and under the influence of mainland influencers and short videos, they have largely embraced mainland food and slang. Some even shop across the Taiwan Strait for white goods on Taobao, because “their stuff is just really cheap”. A recent viral mainland earworm, Blueprint Supreme (《大展鸿图》), even sparked debate in Taiwan over whether it should be removed from children’s TV channels.

Taiwan seeks to strengthen local identity through policy (de-sinicisation), while the mainland projects its national strength and soft power through its sheer size (mainlandisation).

Whether this “soft influence” is a deliberate cognitive warfare tactic packaged in a non-political way by Beijing, or simply the result of market forces, its core driver remains the rapid rise of mainland China’s comprehensive national power over the past decade. This has created a protracted cognitive tug-of-war between both sides of the Taiwan Strait: Taiwan seeks to strengthen local identity through policy (de-sinicisation), while the mainland projects its national strength and soft power through its sheer size (mainlandisation).

Politics the final, insurmountable divide

Massive recall campaign billboards hanging over Taipei’s streets highlight how politics continues to deepen divisions in Taiwanese society. Yet, regardless of whether Saturday’s recall vote and the subsequent by-election will shift the Legislative Yuan’s balance of power, in the broader sweep of history, these events are but ripples — not crashing waves.

Instead, an intangible, non-political shared living sphere across the Taiwan Strait may gradually take shape in an incremental, almost imperceptible way. Due to policy constraints, it may not resemble the visible flow of people between Hong Kong and Shenzhen, but rather unfold as mainland China steadily draws young Taiwanese into its lifestyle ecosystem through the invisible projection of its soft power. Meanwhile, politics will remain the final, insurmountable divide.

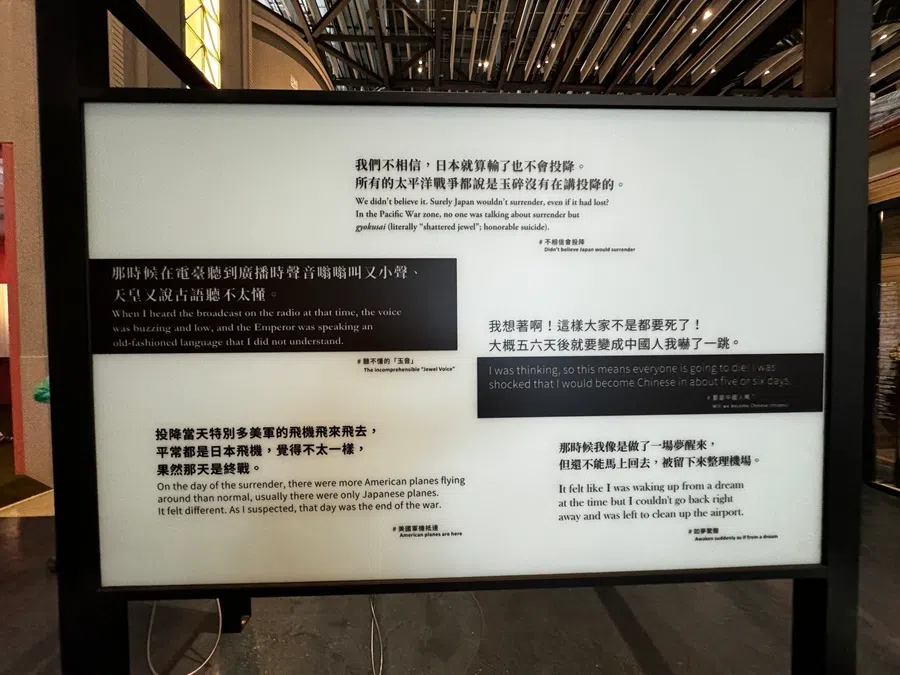

I am reminded of an account from the oral history archives of the National Museum of Taiwan History: in the final days before Japan’s surrender in World War II, rumours of the coming handover spread among Taiwanese under colonial rule. Grappling with their complex identity, a Taiwanese recounted, “I was thinking, so this means everyone is going to die! I was shocked that I would become Chinese in about five or six days.”

I wonder how long this shock lasted.

History has a way of repeating itself. Any change of the status quo in the future brought about by non-peaceful means would certainly be even more frightening. Only by allowing integration to unfold naturally and gently, like water quietly seeping into the soil, nourishing the land — an embodiment of a leader’s wisdom — can cross-strait shocks and public sentiment be assuaged.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “从蒋介石的扬州炒饭到赖清德的虾仁饭”.