School’s out for China’s rural students as classrooms close

Chinese policies to reduce and consolidate coal production in the late 2000s gave rise to an unintended result: empty schools in mining cities.

(By Caixin journalists Huang Huizhao, Zhong Tengda and Denise Jia)

The once bustling main building of Xingshan Second Primary School in Hegang, a key coal mining city in China’s northeastern Heilongjiang province, now stands eerily quiet. Despite appearing relatively new from afar, up close it is evident that disuse over time has taken its toll, with overgrown grass lining the empty schoolyard where children once played.

Instead of students, the school’s lone inhabitants are now an elderly couple, who serve as caretakers, passing their time by raising chickens and geese on the grounds. An occasional bark from one of the couple’s dogs punctuates the silence, echoing across the empty campus.

On a recent visit, former student Liu Wei was struck by the desolation compared with how it once was. He recalled years ago when the school was bursting with youthful energy, with over 50 students in each class, predominantly the children of coal miners.

“The heating in the building still works, and windows and doors are all intact, but it has stayed idle like this for eight years,” said Liu.

The empty schools in mining cities such as Hegang is the unintended result of a policy that started in 2016, when the central government set out to reduce and consolidate its coal production to tackle overcapacity after a decade of breakneck growth. Over the subsequent four years, annual coal production capacity was cut by more than 800 million tons, resulting in nearly 2 million people losing their jobs by 2020, according to the China Coal magazine.

After the mines closed, the residents left, with the local population in Xingshan district tumbling by half to 20,000 in the last decade. The massive outflow has left the area virtually devoid of young people, with the inhabitants now mostly elderly residents, forcing all four primary schools in the area to close.

China’s population decline is “getting close to irreversible”, making its “long-term economic prospects doubtful” — Peterson Institute for International Economics report

Hegang is not alone. An outflow of people and the record low birth rate nationwide have led to a drastic reduction in school-aged children in many former industrial cities and villages across northeast and central China. This trend is replicated across the country, which experts predict could see the number of primary and middle school students tumble by almost a quarter in the next ten years.

A major part of the problem is the decline of China’s total fertility rate — total births per woman over her childbearing years — which according to a January report by US-based Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) is about 1.0. That is far below the replacement level of 2.1, a value generally considered necessary to maintain current population levels.

China’s population decline is “getting close to irreversible”, making its “long-term economic prospects doubtful”, said the PIIE report.

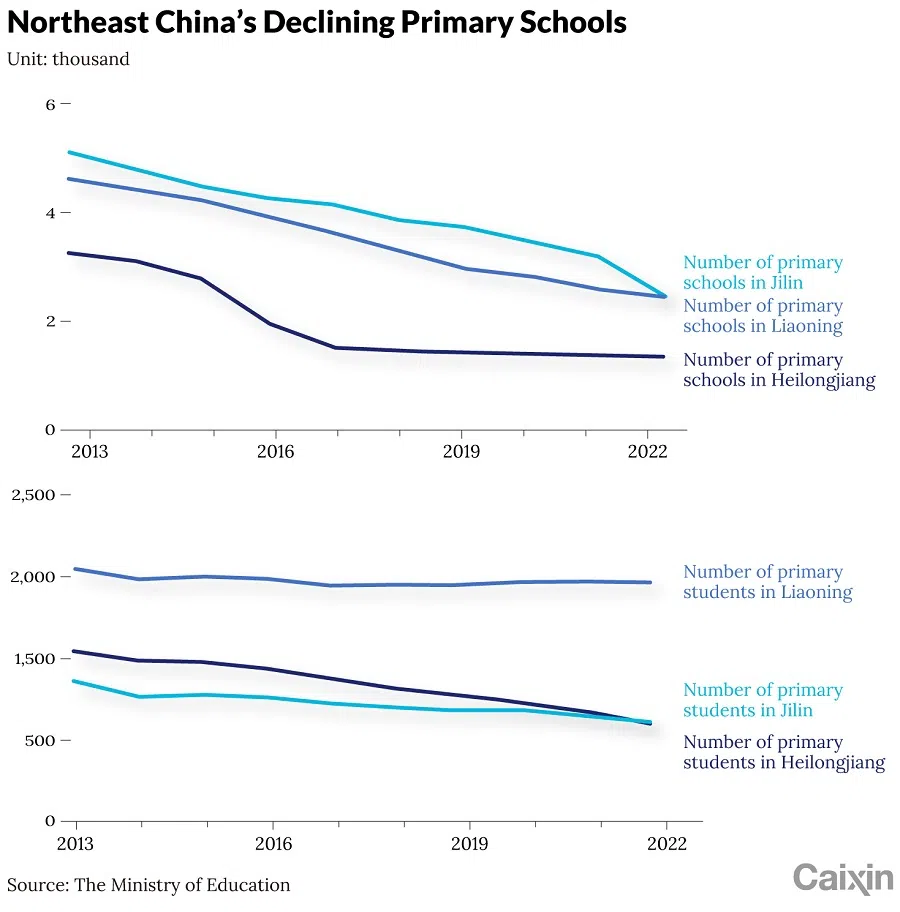

The scale of school closures over the last decade shows how the falling number of kids is affecting China’s education system. In Heilongjiang province alone, nearly 60% of primary schools — over 1,900 — were closed between 2013 and 2022. Jilin saw the closures of more than 2,600 primary schools, over half of its total, while Liaoning shut down nearly 2,200, almost half the total.

Reallocation of resources

Unsurprisingly, the rapid decline in school-aged children and subsequent school closures have prompted central and local governments to rethink the allocation of educational resources. And while many provinces are just beginning to see a decline in primary school-aged children, Heilongjiang and Jilin have been experiencing this downward trend for years.

“We visited a county-level city in northeast China and were told that only 1,200 children were born in 2022,” said Liu Shanhuai, a professor at the China Institute of Rural Education Development at Northeast Normal University.

By the time these children reach primary school age, 300 to 400 will have moved away, leaving only 800 to 900 first-graders for the entire county, enough to fill just one school, Liu predicted.

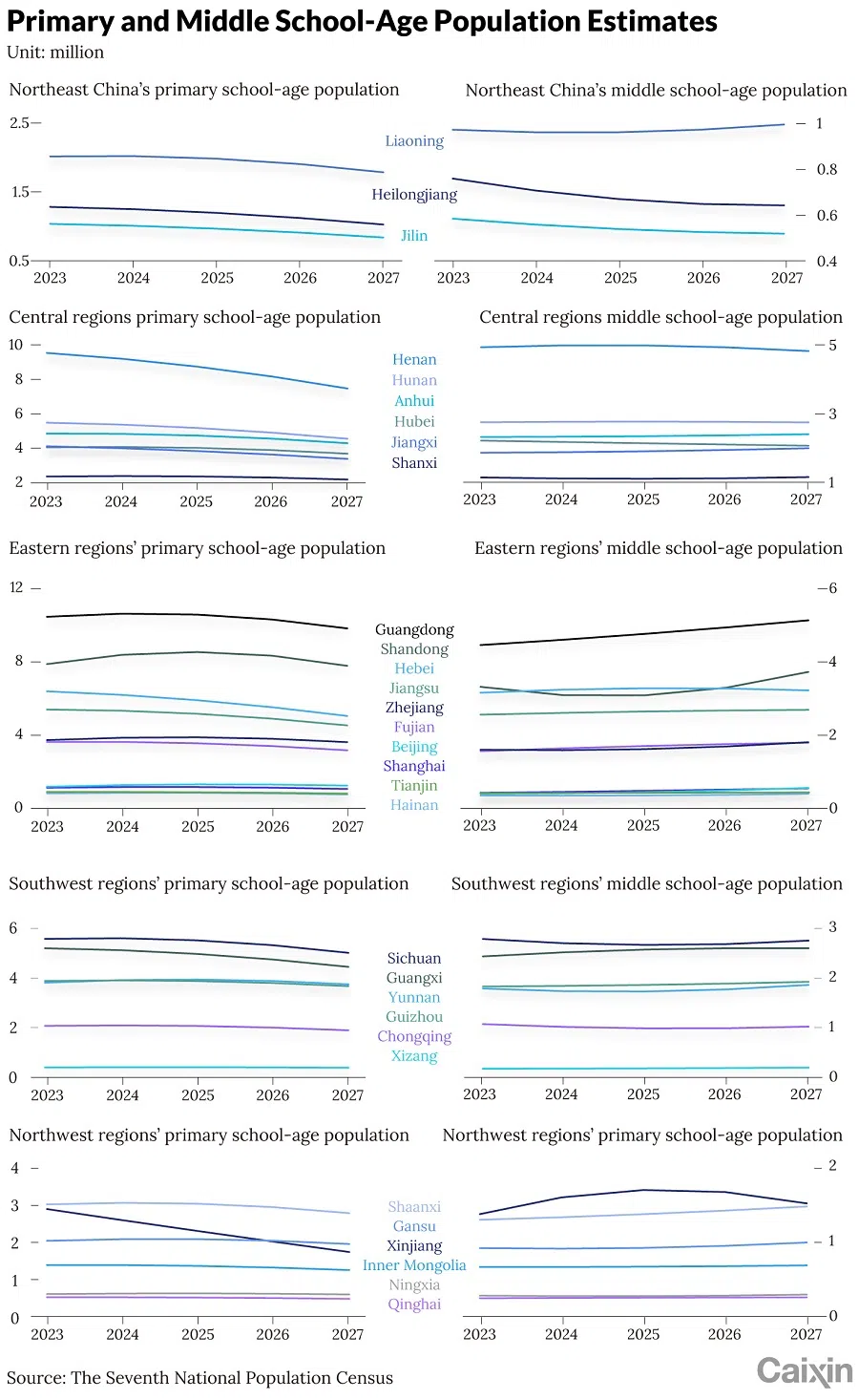

Looking ahead, the reduction in primary school student numbers in Heilongjiang and Jilin is expected to be between 18% and 20% by 2027, while Liaoning will see a decline of about 11%, equating to over 200,000 fewer students, according to estimates by a team led by Tian Zhilei, a professor at the China Institute for Educational Finance Research at Peking University.

... the first challenge for China’s education system is how to consolidate the shrinking national student body into fewer schools.

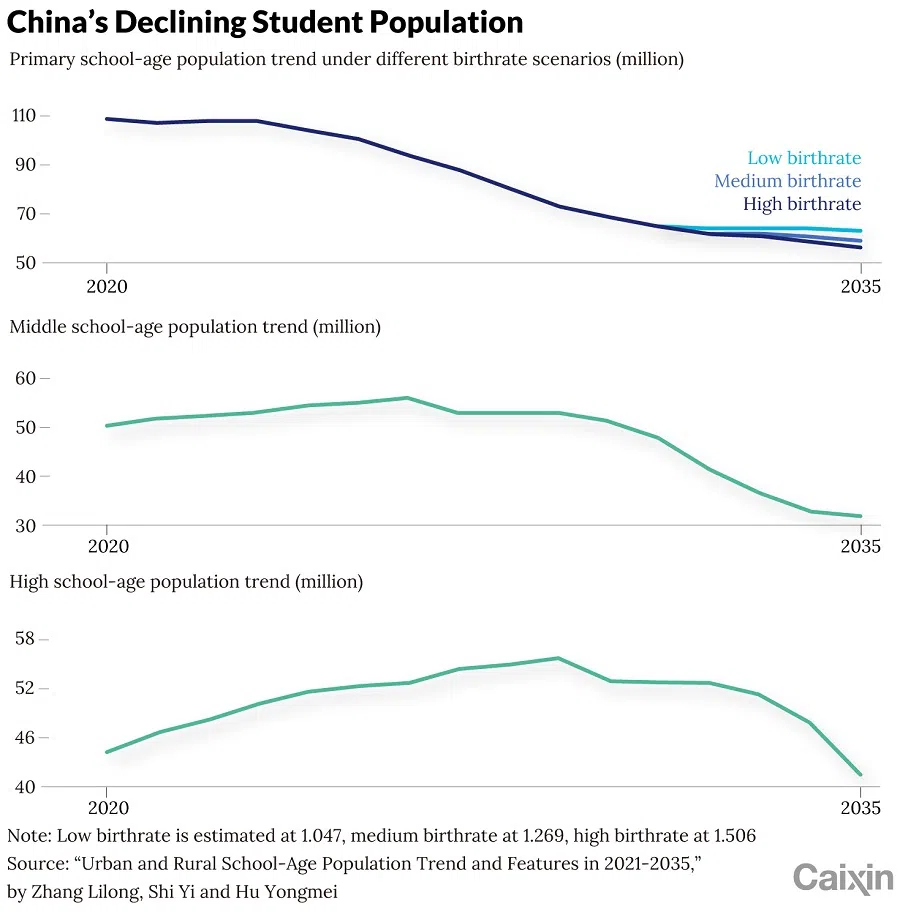

Meanwhile, across the country, the school-age population is expected decline to about 250 million by 2035 from about 328 million in 2021-2022, according to estimates by Zhang Lilong and other researchers from the Capital University of Economics and Business.

Reversing a falling birth rate — if even possible — is a long-term endeavour that began in earnest in 2021, when China announced policy changes that allow each couple to have up to three children. Local authorities have since rolled out subsidies to encourage childbearing.

But the first challenge for China’s education system is how to consolidate the shrinking national student body into fewer schools. It is starting in the vast rural areas, as nearly 90% of China’s more than 1,400 counties are forecasted to experience a decline in their primary school-age populations.

Previously, the government had invested massive resources into developing schools in rural areas. Today, the approach has shifted to concentrating educational facilities into urban centers, with significant funds directed towards building boarding schools in towns and cities. These are aimed at accommodating students from the surrounding lesser populated areas.

Teachers out of work

But this shift is not without its problems. This requires rural families to send their children far from home, likely having a psychological impact on the young students due to the separation. It also means reallocating — and relocating — teachers, which raises another problem: over a million educators without students to teach, possibly left to join the ranks of China’s unemployed.

Yu Ziyu and Hu Yaozong from East China Normal University predict that even if no new teachers are added to the compulsory education system before 2035 and factoring in the natural retirement of existing teachers, by that year there will still be a surplus of 950,000 primary school teachers and 330,000 middle school teachers.

Since 2023, some counties have implemented three-year optimisation plans, accelerating school consolidations and closures. In line with this policy, demand for boarding schools has surged, expanding from junior high schools to primary schools and from towns to counties.

In central regions like Henan, school consolidations have been particularly aggressive, with the provincial government proposing accelerating the construction of boarding schools, with primary boarding schools concentrated in village-level towns and middle schools in county-level towns. As a direct consequence of this policy, in Luoyang, Henan province, 456 smaller schools were shut down in 2023.

This trend has given rise a so-called “companion economy”, creating demand for rental housing and after-school care services.

Elsewhere, Sichuan has become one of the fastest provinces in the west to promote educational redistribution. Nearly 80% of Sichuan’s primary and middle school students live in mountainous areas, making consolidation of schools and students more difficult. In Ganzi Prefecture, a region known for snow-capped mountains and deep valleys, nearly 80% of its primary schools have been shut down or consolidated.

As schools in remote rural areas close, parents have to send children to schools in bigger towns and cities. In many cases, such as in Dancheng county, Henan province, a large number of mothers are also relocating to county cities from nearby villages and smaller towns to be near their children.

This trend has given rise a so-called “companion economy”, creating demand for rental housing and after-school care services. Notably, rural students make up 80% of the population in some private schools in county-level cities, according to Caixin calculations.

The consolidation has led to the emergence of large boarding schools, observed researchers Luo Rongqupi and Tian Zesen from Sichuan University for Nationalities during their study of Ganzi prefecture. They found that the remaining schools have student numbers ranging from 500 to 2,000, averaging about 1,200 students.

By comparison, in 2019, a prefecture-level city Qingyang in Gansu province with a similar rural population as Ganzi, had 2,334 schools with less than 100 students, of which 782 had fewer than 20 students, according to Caixin calculations.

But the burgeoning influx of students and building boom mean that many boarding schools still lack essential amenities, such as showers, sports facilities, and medical clinics and staff, with some dormitories housing over 20 students per room. By comparison, dormitories in Chinese universities usually accommodate four to eight students per room.

According to a survey conducted by the 21st Century Education Research Institute, less than half of the boarding schools surveyed said they have shower amenities, one-third lack sports facilities, and nearly 60% have no on-campus nurses.

In another example of shortfalls, an in-town boarding school in Hunan province, has been left without a boiler due to a lack of funds, leaving students without hot water, according to Lei Wanghong, a scholar at the School of Public Administration at Central South University.

Some scholars caution against continued excessive investment in new infrastructure, arguing that rather than embarking on large-scale demolition of existing schools and construction of new projects, the focus should be on strengthening teachers and educational resources at existing facilities.

Studies indicate that younger children from rural families are more susceptible to bullying at boarding schools.

Boarding school blues

Amid the rapid construction of these new schools and relocation of students, the impact on children’s growth and well-being has not been fully addressed, experts say. Studies indicate that younger children from rural families are more susceptible to bullying at boarding schools.

Lei expressed concern that rural children that have been relocated to county-level towns may not have had equal access to quality education compared with their urban peers. In her research, she found rural students are often marginalised at urban schools due to a lack of support from their parents, both financially and mentally.

Unlike in hometown village schools, where students share similar backgrounds and teachers are more familiar with their students, classes at large schools in county-level cities have classes with dozens of students, overwhelming teachers, exacerbating the sense of disparity between urban and rural families, said Lei.

This has led to behavioural issues, with Ren Lu, the principal of a private rural school in Henan province, saying there has been an increasing number of relocated students expelled from county schools.

Children have been skipping classes, staying up late at night playing video games, and sleeping through classes, ultimately getting expelled and returning home, said Ren, adding that the lack of attention and affirmation from teachers and parents is having consequences.

“In city schools with 60 to 70 students per class, how can teachers remember everyone’s names?” he said.

This article was first published by Caixin Global as “Cover Story: School’s Out for China’s Rural Students as Classrooms Close”. Caixin Global is one of the most respected sources for macroeconomic, financial and business news and information about China.