Turning Lu Xun into a smoking icon is a cruel irony

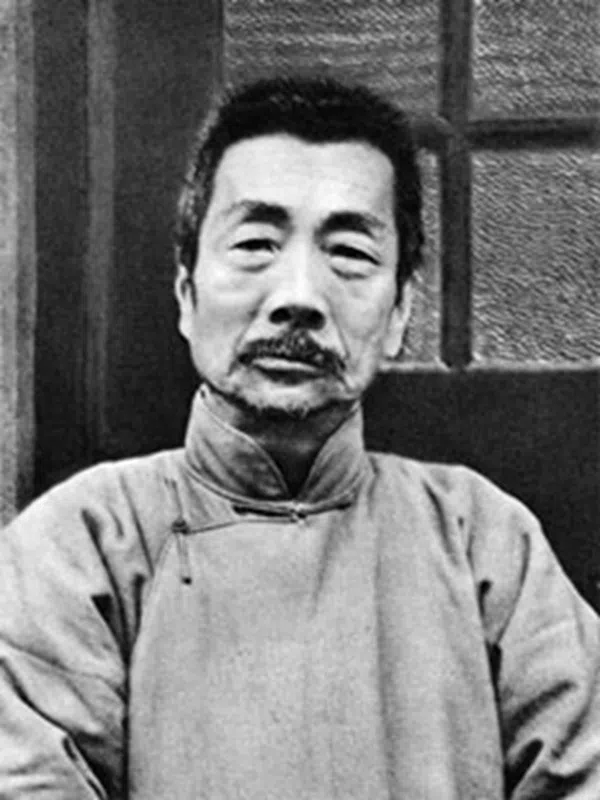

Amid the controversy surrounding a mural of Lu Xun smoking at the Shaoxing Lu Xun Memorial Hall, academic Zhang Tiankan asks: has anyone considered what Lu Xun — the leading figure of modern Chinese literature — would have wanted?

On the evening of 28 August 2025, Ms Sun, who brought attention to the mural of Lu Xun smoking at the Shaoxing Lu Xun Memorial Hall, published a lengthy Weibo response to the matter and apologised for wasting public resources. This is superfluous as it was merely a suggestion to replace the image of Lu Xun smoking instead of a complaint. Since the management of the memorial hall did not take up the suggestion, there is really no need for an apology.

Sun’s so-called “wasting public resources” behaviour isn’t just appropriate — it’s valuable. It sparks important conversations about the use of a smoking celebrity’s image in large-scale public advertising. In doing so, it invites us to think more deeply about how we relate history to the present, how celebrities shape public space and behaviour, and where we draw the line between art and real life.

Although the management of the memorial hall has decided to keep the mural of Lu Xun smoking, Lu Xun’s family should be consulted, and even better if Lu Xun’s opinion could be sought too.

... in truth, he detested and loathed smoking, and was helpless even though he wanted to quit smoking.

Smoking and Lu Xun’s death

Looking to Lu Xun for an answer means taking a retrospective approach — examining his words and actions to observe, analyse and understand his attitude toward smoking. From there, we can reasonably infer how he might feel about the public use of an image of him smoking. And the conclusion is quite clear.

Although Lu Xun enjoyed smoking, it does not mean that he loved smoking. It appeared to be a love-hate relationship, but in truth, he detested and loathed smoking, and was helpless even though he wanted to quit smoking.

Lu Xun’s dislike of smoking was rooted primarily in his scientific awareness and rational understanding of its harms. Trained in medicine, he understood that smoking causes various diseases, including cardio-cerebrovascular diseases, respiratory diseases and various cancers.

In a letter to his partner, Xu Guangping, on 3 December 1926, Lu Xun wrote, “Today I observed slight trembling of my fingers, caused by too much smoking. I have recently smoked as many as 30 cigarettes a day. I need to cut down.” Lu Xun was certainly aware of the dangers of smoking and wished to reduce smoking.

By then, smoking had already damaged Lu Xun’s health and affected his lifespan. At 5:25 am on 19 October 1936, Lu Xun died of illness in Shanghai at the age of 55. The cause of his death has long been disputed, and whether medical treatment was delayed is a historical controversy.

Lu Xun’s chest X-ray, taken at Fumin Hospital in Shanghai in mid-June 1936, still exists. In 1984, Shanghai invited 23 expert doctors to interpret Lu Xun’s chest X-ray. They concluded: chronic bronchitis, severe pulmonary emphysema, pulmonary bullae, chronic tuberculosis in both lungs, and tuberculous pleurisy on the right side. Based on the medical records of the final 26 hours before his death, the experts unanimously agreed that Lu Xun died of spontaneous pneumothorax on his left side due to the above diseases.

However, Lu Xun’s diagnosis has been a subject of debate. His trusted personal physician, the Japanese doctor Sudo Iozo, recorded the cause of death as pneumothorax. On 31 May 1936, American doctor Thomas Dunn — recommended by Soong Ching-ling, Agnes Smedley, and Feng Xuefeng — visited Lu Xun at home and confirmed the diagnosis of pneumothorax. However, Dunn also detected fluid in Lu Xun’s chest and recommended it be aspirated. The controversy lies in whether Sudo carried out this procedure, or whether he delayed treatment.

Sudo claimed he had aspirated fluid from Lu Xun’s chest as early as 28 March 1936 — but Lu Xun’s meticulously kept diary makes no mention of it. This absence has fuelled long-standing speculation: did Sudo falsify medical records to cover up a mistake? The diary does record three fluid aspirations — on 15 June, 23 June and 7 August. If Sudo had acted earlier, as he claimed, there would have been no delay. But if not, it suggests a grave error: a misdiagnosis that may have cost Lu Xun precious time — and possibly, his life.

Lu Xun (known also as Zhou Shuren) was only 55 when he died, and smoking accompanied him for 33 years. In contrast, his younger brothers Zhou Zuoren and Zhou Jianren lived to 83 and 96, respectively.

Lu Xun’s respect for life

Despite diagnostic and treatment controversies, it is undisputed that Lu Xun suffered from smoking-related diseases. Expert diagnoses confirmed these conditions, which ravaged his body and led to his early death.

Lu Xun (known also as Zhou Shuren) was only 55 when he died, and smoking accompanied him for 33 years. In contrast, his younger brothers Zhou Zuoren and Zhou Jianren lived to 83 and 96, respectively.

Given his respect for life and commitment to good health, Lu Xun would likely have opposed smoking and wouldn’t have wanted images of himself smoking to be widely shared.

Lu Xun was deeply aware of the impact his smoking could have on others — and he respected it. He upheld a simple but important principle: his personal habit should never become someone else’s discomfort. In Remembering Mr. Lu Xun, Li Jiye recalled that during a visit to Lu Xun’s home in Beijing, Lu Xun immediately moved to open a window upon noticing Li’s dislike for cigarette smoke.

Li also recounted another visit, in May 1929, when he and Wei Suyuan went to see Lu Xun after his return from Shanghai. They spent hours chatting, during which Wei repeatedly offered Lu Xun a cigarette — only to be politely declined each time. “I’ve stopped smoking,” Lu Xun finally said. But he hadn’t quit entirely — he was simply being considerate. Not wanting to fill the hospital ward with smoke, Lu Xun stepped outside, stood at a distance, and quickly finished his cigarette alone.

Weak self-control

Lu Xun smoked because he felt powerless to quit, revealing the strong grip nicotine had on the brain’s pleasure and reward system. In a letter sent from Xiamen to Xu Guangping in Guangdong on 3 December 1926, he wrote:

“I remember that when I tried to cut back on smoking in Beijing, I ended up snapping at someone. I feel bad about it and realise my temper was awful. But somehow, I have such weak self-control — I just can’t quit. I hope someone will keep me in check next year so I can slowly fix this. I’m even willing to be controlled, so I don’t lose my temper again.”

This shows Lu Xun openly admitting his weakness in self-control and expressing a sincere hope that Xu Guangping would help him quit smoking. At the same time, it reveals the depth of his love and trust in her.

One may therefore infer that if Lu Xun were still alive, he would absolutely not allow the image of him smoking to be publicly displayed, let alone become a popular stop for visitors to “light up his cigarette” or “check in”.

In his entire life, Lu Xun loathed smoking but could not quit it. He clearly knew the harm it brought and sought help from within and beyond his family to quit smoking, but he ultimately failed.

One may therefore infer that if Lu Xun were still alive, he would absolutely not allow the image of him smoking to be publicly displayed, let alone become a popular stop for visitors to “light up his cigarette” or “check in”.

It has been decided that the mural of Lu Xun smoking will stay. Among those who come to “light up his cigarette” or “check in” at this mural and admire the artistic portrayal of the spirit of Lu Xun smoking, how many will actually realise and understand that he loathed smoking and that he died early because of it, having endured immense pain and helplessness?

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “鲁迅会同意以其吸烟图做招牌吗?”.