[Video] I was 11 when the earth shook: A child’s memory of Wenchuan [Eye on Sichuan series]

The 2008 Wenchuan earthquake is a tragedy etched into China’s collective memory, especially for those from Sichuan. ThinkChina’s Yi Jina was only 11 years old when she experienced this major event, and was too young to grasp the scale of what had happened. It took years before she understood what she had survived — and what so many others hadn’t. Even now, old footage and stories from those days still move her to tears.

It was a Monday, and I was off school with a fever. My mum and I had just returned from the doctor’s and were about to take a nap. I was on the bed, changing into pyjamas, while my mum stepped into the living room to answer a call. That’s when the noise started — sharp, sudden and escalating at a terrifying speed. It began with a high-pitched tremble, the glass panels behind me rattling like shaken ice. The sound quickly deepened, every door and window shuddering as if a mob was battering them.

Then, the world began to shake.

Ghost? Robber? Oh no, it was an earthquake!

My first thought? A ghost! (I was only 11). Realising that was a bit absurd, my second guess was that a robber had broken in and my mum was fighting him. Before I could make sense of anything, my mum burst back in, grabbed my hand — and a pillow — and dragged me to the toilet. As we dashed through the living room, dust was pouring from the walls. Objects crashed to the floor in a relentless clatter. Not just in our house, but all around us. That was when it hit me: oh no, it was an earthquake!

Inside the toilet, thick white dust filled the air. My mom pressed the pillow over my head and wrapped me tightly in her arms. We stayed like that for what she later told me was over a minute. I was not scared at all — my mum’s firm embrace made me feel safe, and it never occurred to me that anything could really happen to us. When the tremors died down, my mom grabbed my hand and rushed me down the stairs from our home on the fourth floor. Somewhere along the way, I even paused to put on my pants (I have no idea why I had them with me in the first place).

... some stood barefoot on the asphalt; some were even strolling out of their homes long after the tremors had stopped, as if nothing had happened.

Outside, the world had changed. The buildings of our estate swayed like seaweed in a current, cloaked in thick clouds of dust. We ran past the gate and onto the main road, where the usually wide, open street was already packed. Cars stood still, and in between them were clusters of adults with panic carved across their faces as they stared into the chaos. More people kept pouring in.

Then came another cry: “It’s coming again!” The crowd surged backwards, retreating further into the centre of the street. But there was nowhere left to run.

For half an hour, we lingered there, unsure of what to do next. I was still in a daze. I was too young, too stunned and maybe even too feverish to grasp the full danger of what we had survived. I looked around. Some people had managed to grab their valuables; some stood barefoot on the asphalt; some were even strolling out of their homes long after the tremors had stopped, as if nothing had happened.

Later, my mum told me that even standing in the open might not have saved us. Tall buildings lined the road, and had any of them collapsed, there would have been no escape.

Safest building in Sichuan?

Back in our estate’s courtyard, people gathered to talk. Should we go home? Would it be safe? Just then, two construction engineers came down from one of the blocks, looked at the dusty crowd and joked, “Why run? Even if all the buildings in Chengdu collapse, ours won’t.”

Someone asked why. One of them replied proudly, “These houses were built by our own company, for our own employees. No cutting corners, no cheap materials — only the best.” That unexpected reassurance swept through the crowd like a breeze.

Back then, I had no idea how lucky I was. My mum was with me. We were in Chengdu, the capital city of Sichuan, which was spared major damage and heavy casualties.

When my mum and I decided to return home, we realised we didn’t have our keys, nor did many others. Some tried calling 110 or 119 from the guardhouse phone, but the operator’s voice came through solemnly: “Citizens, please help one another. A major earthquake has struck Wenchuan. Please keep emergency lines clear for rescue teams.” People obediently hung up. Soon after, an uncle fetched tools and helped open our door.

Back home, the first thing my mum did was to switch on the TV. The news was already breaking: a magnitude-8.0 earthquake had struck Yingxiu in Wenchuan county at 2:28pm — just 90 kilometres away, or a two-hour drive.

Back then, I had no idea how lucky I was. My mum was with me. We were in Chengdu, the capital city of Sichuan, which was spared major damage and heavy casualties. We lived in a house built — allegedly — to withstand a magnitude-10 earthquake.

No one could have imagined that just minutes would take so many lives.

Over 88,000 people were dead or missing, and nearly 400,000 were injured. Over 5 million buildings collapsed, and more than 21 million buildings were damaged across Sichuan and beyond. Ten areas in Sichuan were declared the most seriously affected, 41 seriously affected, the majority in remote, underdeveloped counties and towns.

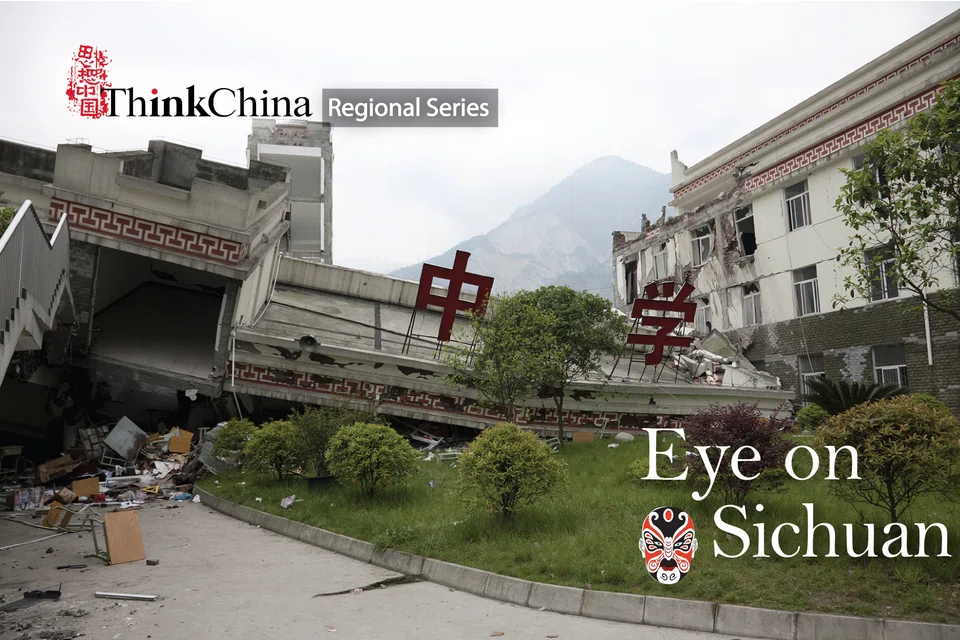

Students were among the hardest hit, breaking the nation’s heart.

What if the earthquake had struck earlier? Would more students have been saved — those still out on the playground, laughing, running, playing in the open air...

Between 2:00 and 2:30 pm, students and workers in China typically return from lunch. At 2.28pm, the earthquake struck without warning. Thousands of students sat trapped in the fragile concrete of their schools, innocent and unprotected, far from their beloved families. The timing was cruel.

UNICEF reported that in Sichuan alone, more than 12,000 school buildings were badly damaged, of which 7,000 were completely destroyed. That’s one in seven.

What if the earthquake had struck earlier? Would more students have been saved — those still out on the playground, laughing, running, playing in the open air — instead of trapped beneath crumbling concrete?

What if those lives lost had lived, like I did, in buildings built with care, with integrity, by people building for their own, built to withstand not just tremors but responsibility?

What if oversight and enforcement had been as strong in rural counties as they were in capital cities?

Sichuan sits atop multiple fault lines. Years of small tremors also bred complacency, making this earthquake all the more catastrophic.

Of course, even in a disaster, there are those who stood tall.

All 2,300 students and staff in Sangzao Middle School survived. Their principal, Ye Zhiping, had long worried about the school’s ability to withstand a quake. Since the 1990s, he had secured funding to reinforce the buildings and held regular evacuation drills. So when the earthquake hit, the entire school was evacuated without injuries in just 1 minute and 36 seconds. Almost all nearby buildings had collapsed.

What if every school had done the same? Would more schools have become sanctuaries, not tombs?

TV captured images of volunteers covered in dirt. My mum always said that they are the most beautiful people she has ever seen.

What I saw in the Chengdu people

The sheer scale of the disaster meant that government and military efforts alone weren’t enough. So people stepped up.

In Chengdu, the vital gateway to the disaster zone, residents stepped forward in different ways: donating money and supplies, donating blood and volunteering in droves to join rescue efforts. TV captured images of volunteers covered in dirt. My mum always said that they are the most beautiful people she has ever seen.

She also told me that many of the local grassroots leaders had died, so after the rescue work ended, many volunteers were appointed on the spot to fill the leadership void, a testament to their courage and commitment.

Everyone understood: this road was for saving lives.

The shortest route to Wenchuan from Chengdu, National Highway 213, was blocked by massive landslides. Sichuan’s transport authorities then swiftly rerouted via National Highway 317 and Provincial Highway 210, winding through Ya’an, Lushan and Baoxing before reaching Xiaojin, Maerkang and eventually Wenchuan. This detour became the now-legendary “West-Line Highway” — the only viable lifeline into the quake zone during those critical early days.

My mum said she took me to see it. I don’t remember, but she described how we stood silently by the roadside with others. The road itself was empty, save for the roar of rescue convoys thundering past.

It was a powerful sight because many workers in Chengdu were from the quake-stricken regions, and with all communication cut off, they waited in fear for word from home. Yet no one drove private cars onto that road, no one got in the way.

Everyone understood: this road was for saving lives.

Schools in Chengdu shut down for a week after the earthquake. Aftershocks were still a real threat, so few dared to sleep indoors. Public spaces became campsites. My school, Huaxi Primary, which is just behind our estate, turned into one. My mum parked just opposite, and we slept in the car for a week. Evenings were lively. Children played. Adults chatted late into the night. We felt like one big family, bound by a strange, gentle togetherness in the face of disaster.

As I write this article, I asked my mom how we got our food and if shops were cleared out like during Covid, she said: “During the day, most of us went home to cook and watch the news. People also went back to work. Shops stayed open. No chaos. No panic buying. Everything continued in order.”

In that fragile time, Chengdu found strength in its people — calm, disciplined and resilient. That, to me, is the Sichuan spirit.

Stories that stayed with the nation

Back then, I was still too young to fully grasp the gravity of the disaster. In fact, I recall having a fun time: no school, no homework, days spent playing with friends and late nights out in the city with my mum. Sleeping in the car was so exciting for me.

But as I grow older, those heart-wrenching images and stories hit me harder. I now understand what we survived, and what so many did not.

A mother was found curled over her baby, who had survived and was still nursing. Her final SMS read: “My dear baby, if you survive, remember mummy loves you.”

A father pulled his son’s lifeless body from the ruins of a collapsed classroom. Carrying him on his back, he walked the long road home, so his boy could rest beside their ancestors.

A doctor from Huaxi Hospital crawled deep into the rubble to amputate a man’s leg in a desperate bid to save him. But despite the effort, the man didn’t survive.

A police officer was rescuing students when he heard his son calling from under the rubble. But his son was trapped too deep, so he made the agonising decision to prioritise others who can be reached faster. He saved 30 lives, but not his son.

Nine-year-old Lin Hao pulled two classmates from the rubble, only to be buried again himself — and luckily rescued. His bravery saw him walk beside Yao Ming at the 2008 Olympics opening ceremony.

The tragedy is etched into our collective memory. Stories from that day resurface online over and over again, reminding us of the heartbreak and hope that rose from the ruins.

Since 2009, 12 May has been marked as National Disaster Prevention and Mitigation Day.

The 2008 Wenchuan earthquake revealed how vulnerable we were, not only to nature’s force, but to human failure.

To a better future

We owe it to the ones we lost to remember. But we owe it to the living to learn, to act and to never repeat the same mistakes.

The 2008 Wenchuan earthquake revealed how vulnerable we were, not only to nature’s force, but to human failure. It taught us, in the most devastating way, what “prevention is better than cure” truly means.

I hope every home will one day be built strong enough to withstand even a magnitude-10 earthquake. I hope every county and every town will have the resources, oversight and preparedness that capital cities do. I hope every school will have a principal like Ye Zhiping. And I hope every child, in times of crisis, will be as lucky as I was.

My mum says buildings in Sichuan are much stronger now!

. . . . . . .

While my story reflects life in the city, we wanted to hear from those closer to the epicentre.

Ms Wang (pseudonym) lives in a remote village in Ya’an, Sichuan, and has lived through both the 2008 Wenchuan and 2013 Lushan earthquakes. Though she escaped suffering major losses, her current reality is far from secure. She shared with us what it was like to survive the aftermath and what it means to still be waiting, 15 years on, for the safety and support that never fully arrived.

She said: “There are still many others who were severely affected. I hope the media and the government can do more to help them. So many people offered help back then. Their kindness shouldn’t be let down, nor their hearts broken.”

This is her personal account. It doesn’t speak for everyone, but it reflects a reality that still exists for some.