What Chew Shou Zi and two art exhibitions tell us about being Singaporean

As Singapore turns 60, two exhibitions at the National Gallery of Singapore explore the layered, transnational identities that shape its art and people — just as the earlier Chew Shou Zi congressional hearing showed that complex, evolving notions of belonging still defy easy labels. Visual art adviser Keong Ruoh Ling gives her take on being Singaporean.

The incredulous look on TikTok CEO Chew Shou Zi’s face when he was repeatedly interrogated by US senator Tom Cotton on his citizenship could make him the poster boy for the celebration of Singapore’s 60th birthday. The whole of Singapore almost gave a resounding “No!” in unison to the specific question posed: if he was holding any other passport apart from the Singaporean one.

Ethnic Chinese person, Chinese national, or an Asian person

The questioning in Congress insinuates an affiliation with the Chinese government that would compromise the data security of end users in America on the platform. The thinly veiled racism in the questions is impalpable only because it’s unclear whom it is directed at: an ethnic Chinese person, a Chinese national, or more broadly, an Asian person.

Reporting for NBC News on 1 February 2024, Isabela Espadas Barros Leal sifted through the responses pouring in across social media, including the one by journalist and digital media consultant Heidi Moore on X: “This is absolutely phenomenal in its revelation of how racist our government is, not just because the question itself is Sinophobic, but also because it’s clear that Tom Cotton can’t tell Asians apart even when they tell him.”

... that moment at the US Congress brought an entire community together...

Singapore's 'imagined community'

Nationalism as a social construction is a common perspective in modernist theories — and it is very much a Singaporean experience. As a small country made up of diverse immigrant and ethnic communities, with only 60 years of nationhood, an existential crisis is almost a default mode for Singapore.

Yet after decades of nation-building — through both tangible and intangible efforts, from countless NDP songs and a world-class airport to an affordable public housing scheme and a local food scene that nourishes both body and soul — a nurtured national identity has finally crystallised in the form of that little red passport, which recently clinched the top spot for global mobility, offering the highest number of visa-free entries worldwide.

If nationalism is indeed an “imagined community” — a concept popularised in the 1980s by political scientist and historian Benedict Anderson — then that moment at the US Congress brought an entire community together, illustrating his definition of a nation as a “political community where people who will never meet or know most of their fellow members feel a deep sense of connection and loyalty”.

Metaphorically speaking, of course — though strictly speaking, it is the ubiquitous social media analytics that now inform nearly every aspect of contemporary life that affirm this observation. A sense of identity is shaped by intangibles, but it is always framed by the tangibles.

Social listening on the other side of the fence also clearly revealed a collective sense of identity — one that, judging by the overwhelming backlash against the senator, reflected an indignant response to the perceived violation of core values that define America as a community. Many Americans called the exchanges “McCarthyism 2.0”, invoking a historical moment now synonymous with political oppression and an exaggerated, biased fear of communism.

Chinese netizens had a field day within minutes after the incident, poking fun at an American — an explicit foreigner, a precise “the other”.

When the monster of the present answers to the calling of the ghost from the past, the core values of the community feel bruised and challenged. Shared values and beliefs are not discernible in mundane daily routines, until they are called out to be defended, justified or refreshed.

Another sizeable and noticeable cluster of netizens chipped in. Known for their nationalistic fervour and prompt, creative memes that flood cyberspace, Chinese netizens had a field day within minutes after the incident, poking fun at an American — an explicit foreigner, a precise “the other”. The episode is made even sweeter by a shared camaraderie with someone ethnically Chinese — the sense of kinship is palpable.

Navigating diversity and belonging: the Singapore case

Nationalism comes in many forms and shapes, and in today’s post-modern world, on the cusp of globalisation 2.0, the question at the core is: how can many live as one?

If Singapore serves as a case study — one inherently bound to fail, as Singapore’s first foreign minister, S. Rajaratnam, once expressed when he said the notion of Singapore as an independent, sovereign state is an absurdity — then this coming together of a collective people from myriad cultures and races remains a very peculiar phenomenon to this day.

... understanding the story of “the others” within the community develops a sense of “us” that is authentic and therefore concrete.

A balancing act must be played: while falling back on history and lineage can accentuate the differences among Singaporeans, these characteristics need to be acknowledged, studied and understood before a new shared identity can emerge.

In brief, understanding the story of “the others” within the community develops a sense of “us” that is authentic and therefore concrete. More often than not, in Singapore’s case — where the categorisation of “them” and “us” is constantly evolving and morphing — this dynamic essentially underpins a sense of dual embeddedness that shapes our identity as one people.

Imagined community à Paris

City of Others: Asian Artists in Paris, 1920s-1940s, an exhibition organised by the National Gallery Singapore from 2 April to 17 August 2025, takes a deep dive into the issue of dual embeddedness against the backdrop of Paris between the two world wars.

École de Paris, is as much a term for an art movement as a catchphrase of a lifestyle. One that is almost synonymous with Montparnasse, an area that is on the left bank of the River Seine in Paris, which came of age in the “roaring twenties”, also known as Les Années Folles, where it would be the heart of intellectual and artistic life in Paris.

Painters, writers, sculptors, poets and musicians came to Paris, unknown and penniless, congregated in Montparnasse for its cheap rent, numerous cafes and the legendary friendly vibe. It was a time and space charged with an overwhelming sense of utopian positivism and expressed in unbridled artistic individualism.

... émigré artists and artisans also brought with them foreign experiences, networks, practices, and materials that interacted and exchanged with French ideas and styles.

The tale is by now familiar; the convivial atmosphere enabled friendships instantaneously. It was said that when Tsuguharu Foujita arrived in Paris from Japan in 1913, not knowing a single soul, but met Chaïm Soutine, Amedeo Modigliani, Jules Pascin and Fernand Léger all in a single night and within a week became friends with Juan Gris, Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. Countless stories and myths are told and retold of this euphoric time that would take up a unique spot in art history, loosely known as the École de Paris.

This congregation of expatriates from diverse origins engaged Modernism on multiple fronts. Unlike earlier narratives that portrayed Paris as the sole hub of artistic discourse during the interwar years, City of Others set forth to reposition Paris in the exhibition.

Paris through new eyes

Whilst artistic migration peaked in Paris during the interwar years, and Paris was widely seen by many of “the others" as a standard par excellence, émigré artists and artisans also brought with them foreign experiences, networks, practices, and materials that interacted and exchanged with French ideas and styles.

In the words of the curator of the exhibition Phoebe Scott “…it also offers a way of reframing the art history of Paris from the points of view of artists who were, variously, foreigners, sojourners, migrants, students, workers or colonial subjects…,

In City of Others, Paris is explored simultaneously as a site of opportunity, connection, creative exuberance and cultural diversity; and also one of exploitation, appropriation, racism and resistance.”

If the stories and experiences of Picasso and Modigliani are constantly quoted as the legends from this period, this exhibition aspires to deal with the names that otherwise fell under the long list of et cetera; thereby effectively offering an alternate trajectory of Modernism, steering it away from the Eurocentric version.

Equally, if the process of ‘othering’ is socially constructed through cultural narratives and existing power structures, then spotlighting ‘the others’ within the established canon of art history inevitably renders the structures wobbly and frees up spaces for new stories.

Liu Kang’s identity as a Singaporean artist is shaped by his birth and formative education in China and France, enriched further by an extensive network and deep relationships beyond Singapore...

Singaporean artists in Paris

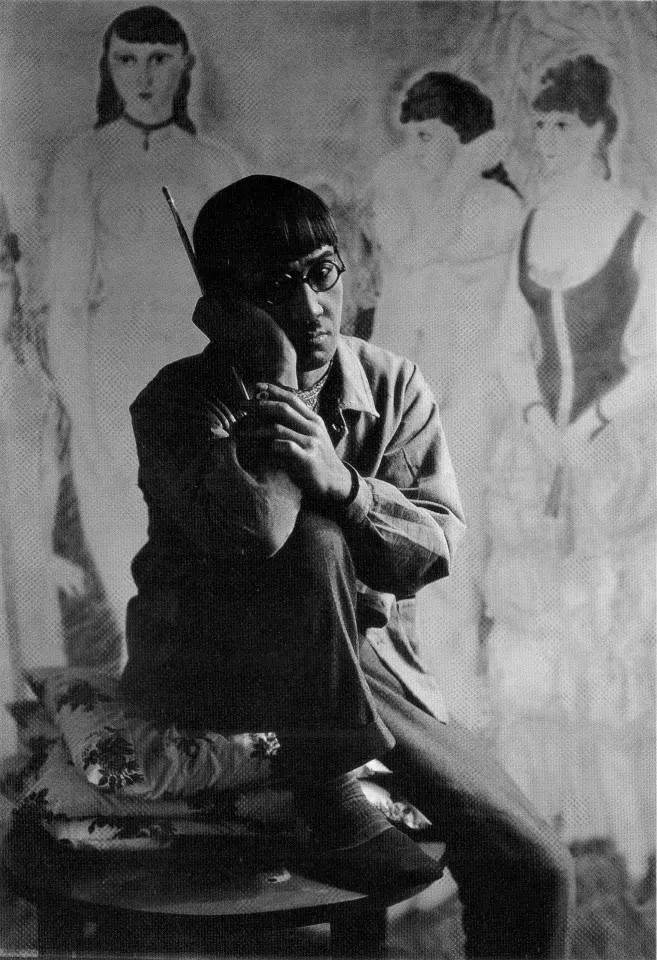

Liu Kang, always known as a first generation artist within the Singaporean context, is shown as a young artist who was trying to make the best of his sojourn in Paris. He wrote to his teacher Liu Hai Su in 1931 from Paris, “Your painting that was shortlisted, of a snowy scene, was displayed in Room No. 14. …Zhang Chengjiang submitted two carvings, which were both displayed. It is truly delightful that he has demonstrated what Chinese carvers are capable of. Quite notably, as many as twenty-odd Japanese artists were featured. Even though only a small number of their works were of incomparable genius, the assiduous and long suffering attitude of these people was quite admirable.”

Liu Haisu, founder of the Shanghai School of Fine Arts in 1912 and also a highly respected Chinese artist of the 20th century, was already back in China then, having spent approximately a year in Paris from 1929 to 1930, where he lodged with Liu Kang and submitted his works for entry to the Salon d’Automne’s exhibition in 1931. In those few words, one catches a glimpse of the friendship between the pair, the aspirations of Asian artists in Paris, and the network amongst the different ethnic communities.

Poignantly, it highlights that Liu Kang’s identity as a Singaporean artist is shaped by his birth and formative education in China and France, enriched further by an extensive network and deep relationships beyond Singapore that he sustained throughout his life, adding nuance and depth to his identity as a Singaporean artist.

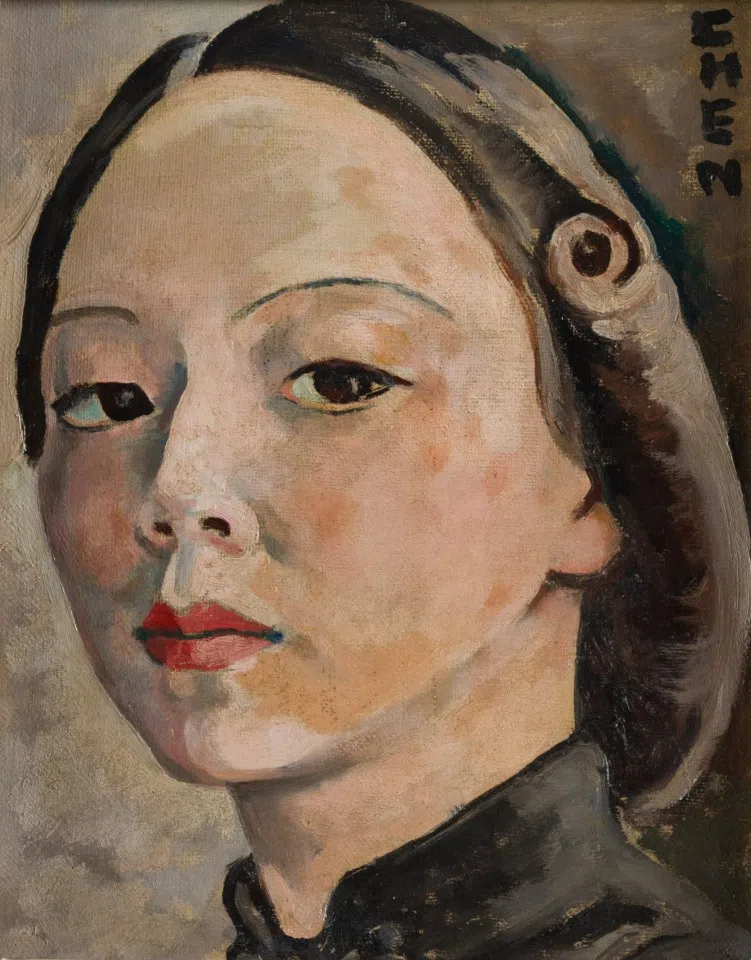

Georgette Chen, another Singaporean artist featured in the exhibition, spoke specifically about her identity as a compounded product of her French and American education, Chinese ethnicity, experiences during the two world wars, and her years in Paris.

Her fluency in French and bourgeois, cosmopolitan tendencies — reflective of a privileged upbringing — set her apart from other Asian artists. Anecdotal stories like these supplement known narratives and add dimensionality to an individual; dual or multiple embeddedness is common, as identity is never singular but always layered.

Layered identities

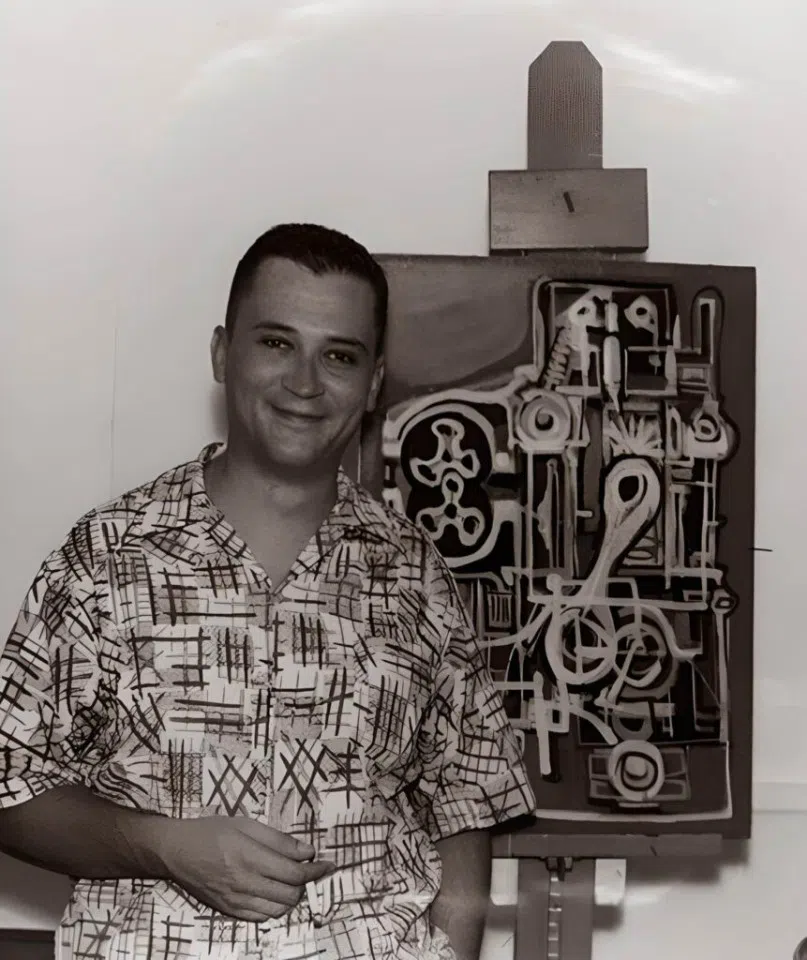

A layered, transnational identity and diverse cultural and artistic influences are clearly reflected in the works of Fernando Zobel, featured in another exhibition organised by the National Gallery of Singapore.

Fernando Zobel: Order is Essential (9 May to 30 November 2025) charts the journey of an artist of Spanish ethnicity born in Manila, educated in the US, who eventually moved from the Philippines to Spain.

He engaged deeply in discourse and in practice with his Manila peers in the 1950s to nurture and develop Filipino Modernism. His personal Filipino art collection became the seed collection of the Ateneo Art Gallery in Manila, while his Spanish collection helped establish the Museo de Arte Abstracto Español in Cuenca, Spain. Inspired by American abstract expressionism, Chinese calligraphy and Japanese Zen gardens, Zobel was featured in the Spanish pavilion at the 1962 Venice Biennale and authored the seminal Philippine Religious Imagery book in 1963.

Singaporean as an identity will always face the likes of Tom Cotton who will always struggle to understand a pluralistic Modernism with a diverse cultural, linguistic, and religious landscape.

In the words of the Filipino historian Benito Lagarda who was also a friend, “Philippine by birth, Spanish by descent, cosmopolitan by training.”

A national institution rightly embodies the ethos and pathos of its country. The two exhibitions at the National Gallery of Singapore exemplify a research approach that highlights a nuanced and malleable sense of identity — something close to our hearts and embedded in our DNA as a nation largely made up of immigrants. In the words of poet Lee Tzu Pheng:

My country and my people

I never understood.

I grew up in China’s mighty shadow.

With my gentle, brown-skinned neighbours;

But I keep diaries in English.”

(Lee Tzu Pheng, My Country and My People, 1980)

This sense of belonging and identity that is framed by our lineages, informed by our reality, and consolidated by our shared values will always be a work in progress.

If the episode of the interrogation of Chew Shou Zi ignited a collective response that tugs at our hearts, the message being taken away perhaps is not about a narrow nationalistic sentiment, but that constructed sense of belonging is a multifaceted one and constantly evolving; Singaporean as an identity will always face the likes of Tom Cotton who will always struggle to understand a pluralistic Modernism with a diverse cultural, linguistic, and religious landscape.

And a message coming through for the Chinese netizens who promptly celebrate the “Chineseness” of the episode, reducing it to a debate between a triumphant ethnically Chinese person and a not so clever Anglo-Saxon would be: that the Chinese diaspora is an expansive and complex group and “Chineseness” means quite different things in different time and space — and more importantly, some of us have indeed made roots in new homes.