White lanterns and ugly rabbits: The no-nos of CNY decorations

A mall in Shenzhen came under fire for putting up white lanterns with black text as part of its Chinese New Year decorations, while an "ugly" rabbit-shaped light decoration was removed from another mall in Chongqing. Academic Zhang Tiankan muses on tradition and innovation, and the evolution of traditional decorations.

Recently, as part of the Chinese New Year festivities, the COCOPARK mall in Shenzhen put up rows of white lanterns with black text along a pedestrian bridge. After photos of the lanterns went online on 11 January, netizens roasted it as "bad luck" and "totally Japanese"; some residents even called to complain that these white lanterns were not suitable for the occasion. The mall took in these criticisms and coloured the lanterns red, and also put up Chinese lanterns.

One important reason for the complaints against the "unlucky" black-and-white lanterns is that they did not fit the traditional symbols and colours of Chinese New Year, which in turn stem from thousands of years of Chinese cultural DNA. While culture can change with the times, the roots will remain, and the Chinese will generally stick to such cultural symbols and colours, and it is difficult to go against the cultural DNA formed over hundreds and thousands of years.

Any change in shape or colour - especially colour - and the traditional flavour and essence of Chinese culture is lost.

There are many symbols of Chinese New Year: couplets, drawings, flowers, door gods or guardians, peach wood charms, the character "福" (fu, good fortune), the zodiac animals, lanterns, and fireworks, with red and yellow the main colours. These symbols and colours represent hopes and blessings of renewal, joy and celebration, good fortune, and respect for gods and ancestors - these are the substance and form of Chinese New Year, its essence and spirit, showing how the Chinese think and act.

Much ado about lanterns

When such perceptions and sentiments build up, they form behavioural norms, vibes and atmospheric colour, such that people cannot break away from the culture and climate, or they feel strange and uncomfortable.

Lanterns are a classic symbol of Chinese New Year. Even on other occasions, Chinese lanterns are bright red, symbolising happiness and celebration. Any change in shape or colour - especially colour - and the traditional flavour and essence of Chinese culture is lost.

To the Chinese, black text on white lanterns goes against traditional culture. The colours red and white are used in weddings and funerals respectively, where the colour white symbolises sadness and separation, in contrast with the joy and unity of red.

Images, symbols and decorations that do not fit Chinese culture could be considered a mismatch at best and bad luck at worst, and naturally, people would object.

Images, symbols and decorations that do not fit Chinese culture could be considered a mismatch at best and bad luck at worst, and naturally, people would object. Of course, generally Chinese people would want to gather with family over the festival and pray for prosperity, good fortune and happiness for the future, and anything that goes against that mindset would be seen as unlucky.

Symbolism and luck

The animals of the zodiac are also an important part of Chinese New Year, and a frequent subject of festive drawings. But whichever animal it is - from the majestic tiger to the ugly rat - they are all depicted as nicely as possible, even beautified and exaggerated, so that people feel these animals are relatable to human sentiments, as they are endowed with cute, adorable, lively or cheerful characteristics during the festive season.

Drawings and lanterns featuring rabbits are an important visual element that adds colour to this Year of the Rabbit. Cities like Chengdu, Xi'an and Shanghai have come up with all sorts of nice, cute rabbit designs, which fit the celebratory atmosphere and that residents like and welcome.

But innovation and growth also have to move step by step and evolve over a long time, based on tradition.

But the rabbits in some places do look ugly, like the rabbit-shaped light decoration at Sanxia Square in Shapingba, Chongqing, which netizens called "hideous and frightening", prompting the relevant agencies to remove it. Of course, the intention was not to design an ugly rabbit to put off the public, but "the result was way off the design". People complained about the rabbit in Chongqing and the white lanterns in Shenzhen because they went against the symbols or colours of Chinese New Year and fundamentally did not fit Chinese cultural DNA.

While there is general consensus on festive atmosphere and feeling, there is also the wish to be original - innovation and growth also lead to cultural development. But innovation and growth also have to move step by step and evolve over a long time, based on tradition. Like changes in biological genes, it takes long effort and adaptation.

When cultures evolve

In fact, China's lanterns have also evolved. Lanterns only came about after the Qin and Han dynasties; paper lanterns came after paper making was invented during the Eastern Han dynasty. During the reign of Emperor Xuanzong in the Tang dynasty, lanterns were displayed and the tradition began of admiring lanterns on the fifteenth day of the new year, to celebrate peace for the nation and people.

The sparkling lights symbolised blessings from a mythical dragon of many colours, as well as a flourishing people and country, which is why Chinese lanterns are also known in Chinese as 灯彩 (deng cai, lit. "colourful lights"). Every year around the fifteenth day of the new year, people put up red lanterns symbolising reunion, to create a celebratory atmosphere.

Lanterns also bring together arts like drawing, paper cutting, paper crafts (making items out of paper), and sewing. Generations of lantern craftsmen inheriting and developing their art have led to a rich array of lanterns and outstanding workmanship: from palace lanterns, gauze lanterns to regular lanterns, in the shape of people, scenery, flowers and birds, dragons and phoenixes, and animals, as well as lanterns with revolving images for people to admire and play with.

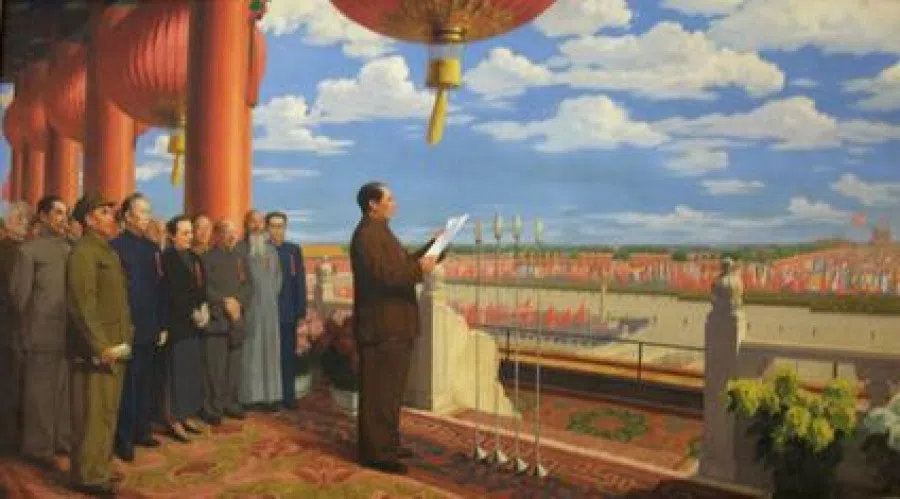

Today, the lanterns seen in China during festivals are almost all of the round, red variety, so that many people think they are traditional ancient lanterns, which is not completely true. One story goes that the oval-shaped lanterns were first created by two Japanese in China, one possibly called Onozawa Wataru (小野泽亘, Chinese name 肖野 Xiao Ye) and the other surnamed Morishige or Morimo (森茂 Sen Mao), who combined Japanese-style lanterns with the frame of Chinese lanterns to create eight large red lanterns that were hung at the Tiananmen Tower during the ceremony of the founding of the People's Republic of China on 1 October 1949. (NB: Another version has it that the eight lanterns were designed by Zhang Ding (张仃), who led the art design of the founding ceremony, and Zhong Ling (钟灵), who participated in the design of the emblem of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference and the national emblem of the People's Republic of China.) After that, such lanterns became the mainstream in China.)

Cultural development and innovation must synergise with cultural genes. With opportunity and timing, such changes could then be assimilated and become part of a people's culture.

But from the Eastern Han dynasty to the Tang, and through the Song, Ming and Qing dynasties, lanterns were generally oval and round, forming the basic pattern of traditional ancient lanterns. The lanterns in the movie Raise the Red Lantern are oval, the basic shape of Chinese lanterns after the Ming dynasty, as are those depicted in the Ming dynasty painting Xianzong at leisure on the Fifteenth day of the New Year (宪宗元宵行乐图, referring to the Emperor Chenghua).

So, even the modern Japanese-designed oval-shaped lanterns evolved from the shape of ancient Chinese lanterns, while also inheriting the red and yellow colours. Hence, the evolution of the lantern came about through a combination of innovation and tradition, and fitting the needs of the times.

Today's lanterns, improved with modern technology, also take into account Chinese culture. For instance, LED lanterns use LED technology with a PVC or acrylic shell, making them low-carbon, aesthetically pleasing, environmentally friendly and durable, as they are able to withstand all kinds of weather. This is also a combination of modern technology and tradition. An acrylic shell looks vibrant, and the traditional fiery red makes it even more festive and eye-catching.

Whether traditional or LED lanterns, red lanterns symbolise family togetherness, a thriving career and prosperity, as well as happiness, light, life, and completeness. Cultural development and innovation must synergise with cultural genes. With opportunity and timing, such changes could then be assimilated and become part of a people's culture.

Related: Not sweating the small stuff: Blessings for a happy Chinese New Year | [Chinese New Year Special] A bygone era: Chinese New Year celebrations during the time of the Republic of China | Lunar New Year, Chinese New Year or "China's New Year"? The rise of (China's) identity politics | [Photo story] A cold start to the Year of the Rabbit

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)