[Big read] Penang leads Malaysia’s semiconductor charge

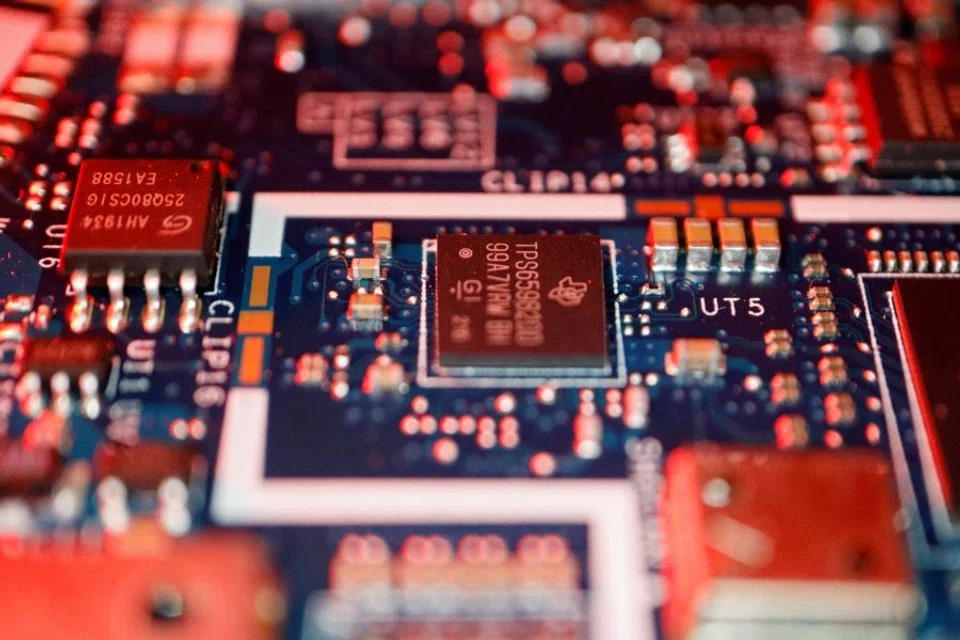

Malaysia has become an important player in the global semiconductor supply chain as major firms flock to Penang. Lianhe Zaobao correspondent Seoow Juin Yee looks into the situation.

With semiconductor makers flocking to Southeast Asia in recent years because of the China-US competition, Malaysia has become the unexpected winner. And among the Malaysian states, Penang — known as the “Silicon Valley of the East” — is proving to be the most attractive to multinational corporations (MNCs).

Last year, Penang drew US$12.8 billion in foreign direct investment (FDI), exceeding the total from 2013 to 2020 combined. Some big-name investors in the state include Intel, which set up a US$7 billion plant; Micron, which set up its second assembly and testing plant; and Infineon, which has announced plans to invest US$5.4 billion to expand its facilities over the next five years.

Penang Chief Minister Chow Kon Yeow told Lianhe Zaobao that the rejuvenation of Penang’s semiconductor industry over the last five years was a case of being in the right place at the right time.

The US’s decision to block exports of chips and other related technology to China drove many semiconductor producers to seek manufacturing bases outside China, Chow said. “This benefited Southeast Asia, which is right at the centre of Asia-Pacific, and created new opportunities for the semiconductor industry in Malaysia.”

Penang’s success no accident

Chow emphasised that even though global conditions had been favourable, Penang’s success was in no way an accident but based on an industrial base that took over 50 years to build.

In his report “A Look Back at How Penang Learned to Shine Through Its Electrical and Electronics Sector”, Francis Hutchinson, senior fellow and coordinator of the Malaysia Studies Programme at the ISEAS — Yusof Ishak Institute, Singapore, observed that after Lim Chong Eu became the chief minister of Penang in 1969, he made economic growth a priority and established a government investment vehicle in the form of the Penang Development Corporation. All resources that were constitutionally available were mobilised towards the development of the electrical and electronics (E&E) sector, as recommended by the 1970 Nathan Report.

“An investor recently said that they would choose to either invest in Penang or venture outside Malaysia. This is the advantage that Penang has built up over 50 years of industrial development.” — Chow Kon Yeow, Chief Minister, Penang

Penang’s Bayan Lepas became the first free trade zone established in Malaysia in 1972, and it became an E&E manufacturing hub not just within Penang but also for the whole country. The first cohort of eight MNCs to invest in Penang, nicknamed “The Eight Samurai”, were National Semiconductor, Advanced Micro Devices, Intel, Litronix, Hewlett-Packard, Bosch, Hitachi and Clarion.

By 1980, Penang had attracted 25 electronics assembly firms, creating 25,000 jobs. By 1990, there were some 500 international and local enterprises based in its industrial park, employing 120,000 people. Manufacturing continued to develop, contributing to 47% of the state’s GDP that year; nationwide, the proportion was only 27%.

In 2010, there were 1,400 manufacturing companies that provided 200,000 jobs, and it made up 46% of the state’s GDP. Penang’s per capita income was 17% higher than the national average.

Chief Minister Chow said that although more than half a century has passed and some members of the Eight Samurai have restructured and changed their names, they continue to operate and expand in Penang, illustrating the confidence they have in the state.

“Penang also continues to be the first-choice destination for foreign investors entering Malaysia,” Chow said.

He added, “An investor recently said that they would choose to either invest in Penang or venture outside Malaysia. This is the advantage that Penang has built up over 50 years of industrial development.”

A whole ecosystem

One of the Eight Samurai, Germany’s Bosch, first set foot in Malaysia in 1923, and its largest manufacturing base in Southeast Asia is currently located in Penang.

Last August, Bosch added a new semiconductor back-end site in Penang, for the final stage testing of automobile chips and sensors. As of 31 December 2023, Bosch has invested a total of 235 million ringgit (US$50 million) in Malaysia and employed more than 4,000 people.

Penang hosts the largest concentration of Bosch manufacturing facilities because of fundamentals such as regulatory familiarity, logistical efficiencies, supply chain synergies and hiring processes that are already well-established. — Klaus Landhaeusser, Managing Director, Bosch Malaysia

Klaus Landhaeusser, managing director of Bosch Malaysia, said that Bosch’s decision to establish its new facility in Malaysia was driven by several strategic advantages.

“As the sixth largest exporter of semiconductor in the world, Malaysia has built up an unparalleled ecosystem for semiconductors,” he said, adding that Malaysia is an important hub in the global semiconductor supply chain located in Southeast Asia, one of the world’s fastest-growing economies.

Landhaeusser said that Penang hosts the largest concentration of Bosch manufacturing facilities because of fundamentals such as regulatory familiarity, logistical efficiencies, supply chain synergies and hiring processes that are already well-established.

Penang is also home to one of the most important production lines of another one of the Eight Samurais, Intel. The chipmaker first entered Penang in 1972 and within three years, Intel’s Penang facilities were already making up more than half of its total assembly capacity. Today, Intel’s operations in Penang have expanded to US$5.9 billion in scale; three years ago, the chipmaker invested US$7 billion to build a new facility — its first advanced 3D chip packaging plant outside the US, slated for completion this year.

AK Chong, vice-president and managing director of Intel Malaysia had previously said, “When you have a new technology introduced to a country, you’re bringing in a lot of ecosystem suppliers,” describing it as a chain effect that also helped to raise the overall skill level of the labour pool.

There are currently ten industrial parks in Penang, complemented by an international airport and other facilities for logistics and shipping. Other amenities include international schools, institutions of higher learning and healthcare, making for an attractive home for expatriates.

The semiconductors produced in Penang are used in medical devices, solar panels and electronics manufacturing. A number of small and medium-sized enterprises have also come along with the MNCs that have set up bases in Penang as their suppliers, contributing to the growth of the local E&E sector.

Penang is an island, and thus faces natural constraints in the supply of water and land.

Overcoming land and water scarcity

Semiconductor manufacturing can be divided into design, production, packaging and testing. Malaysia’s forté is in the latter two, where it has a market share of roughly 13%.

Packaging and testing refers to processing wafers that have passed testing in accordance with the product model and function to obtain independent chips. The process requires a vast amount of clean water.

Penang is an island, and thus faces natural constraints in the supply of water and land. Chief Minister Chow is candid about the severe challenge of water shortage on the island, which has been exacerbated by climate change and water pollution.

Penang is currently only able to meet 15% of its total demand for water and relies on neighbouring Kedah to make up the rest. As demand increases, the development of Penang’s semiconductor industry will be affected if it cannot effectively ensure a stable water supply.

The Penang government has planned to complete several short to medium term projects by 2028 to bolster the state’s water supply. There are also plans to divert water from nearby Perak, which would resolve Penang’s water supply woes by 2030.

But the challenges do not stop there: the Penang state government has projected that all available land for development will be used up by 2030. To address the issue of land scarcity, the Penang Development Corporation is mulling over land reclamation as a way to increase its reserve of land, and is studying reclaiming about 120 square kilometres of land on Seberang Perai mainland for the construction of a new industrial park.

Developing a comprehensive value chain in the country

As the semiconductor industry becomes a pillar of the country’s economy, several Malaysian states are also after a piece of the pie.

Selangor has the backing of the federal government to develop the biggest industrial park dedicated to the design of integrated circuits (IC) in Southeast Asia, and is offering government subsidies, tax breaks and visa exemptions, among other incentives, to attract global electronics companies and talent. The project is expected to start operation in July, and Malaysia hopes that it will be the boost necessary to make it a global IC design hub.

Sarawak Premier Abang Johari Openg recently announced the establishment of the Sarawak Microelectronics Design (SMD) Semiconductors to invest in compound semiconductors. The company will be working with a British company to construct a chip design centre in the state.

Johor has also made its move, and construction of its first semiconductor component plant began last year. The facility is expected to start operations in the fourth quarter of this year.

There have been worries that competition from the various states will have an impact on Penang’s standing as a semiconductor hub. But some analysts believe that the different states each have their own strengths and weaknesses, and can focus on different segments of the supply chain so as to complement one another to make up a comprehensive semiconductor value chain.

“The states may not necessarily be competing against each other, instead they can focus on their strengths and develop different areas of semiconductor manufacturing, enhancing Malaysia’s overall competitiveness.” — Chua Tia Guan, a senior Malaysian analyst

Chua Tia Guan, a senior Malaysian analyst, said when interviewed that Penang’s semiconductor ecosystem is already in place, and other states could learn from Penang’s model to achieve rapid development.

“The states may not necessarily be competing against each other, instead they can focus on their strengths and develop different areas of semiconductor manufacturing, enhancing Malaysia’s overall competitiveness,” he said.

Chief Minister Chow observed that the semiconductor ecosystem is wide-ranging, with IC design making up just one category. The Penang government will continue to work to attract more diversified investment, including working with the federal government to draw more IC design firms, so as to strengthen the ecosystem.

... semiconductor research and development and design require massive investment and advanced professional know-how — an area where the country falls short.

Exploring upstream industries

Malaysia’s semiconductor industry is mainly concentrated on packaging and testing — the downstream of the supply chain, where there is lower added value and lower profits. The authorities hope to change that by riding on the current momentum to elevate the industry’s position to the middle and high end of the value chain.

Wong Siew Hai, president of the Malaysia Semiconductor Industry Association, said that as demand is currently strong, the country should seize the opportunity to develop upstream industries. She said, “We will be able to build a brand new upstream ecosystem and become the first country in Southeast Asia to have a comprehensive semiconductor value chain.”

However, semiconductor research and development and design require massive investment and advanced professional know-how — an area where the country falls short.

ISEAS’s Hutchinson said that although a large number of MNCs have set up manufacturing bases in Malaysia and carry out very sophisticated tasks internally, the amount of linkages they have with local firms is relatively under-developed, and very little technology transfer takes place.

The wafer fabrication side has been under-developed as “the local base of supplier firms is not as dynamic and engaged in value-added tasks as could be, this limits the innovative potential.”

According to Hutchinson, the model of industrial development pursued by Japan, South Korea and Taiwan has been about pursuing local technological capabilities and know-how, which has put them at the front end of the semiconductor industry. He explained how the focus on attracting investment has resulted in a technological gap as “the model adopted in Southeast Asia in places like Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand has been to provide an enabling environment for MNCs to produce components and other E&E items.”

Chief Minister Chow pointed out that among the MNCs investing in Penang in recent years, several are in the business of chip design, and local Penang firms were able to learn from these enterprises.

He said, “We are also seeing increasingly more local start-up firms, including SkyeChip and Oppstar. They have started going into design and testing.”

“The talent shortage is further exacerbated by local talents preferring overseas jobs due to the promise of higher pay, and the difficulty in hiring skilled foreign workers.” — Landhaeusser

Raising the local salaries of engineers and attracting overseas talent

According to Chief Minister Chow, “Penang will continue to strengthen the development of the downstream industry, and at the same time actively develop the upstream. This is what we want to do most.”

This is an endeavour that will require a global talent grab.

Klaus Landhaeusser of Bosch observed that the industry demands more engineers specialising in chip design, fabrication, marketing, sales and management, yet there is a shortage of such talent in Malaysia. “The talent shortage is further exacerbated by local talents preferring overseas jobs due to the promise of higher pay, and the difficulty in hiring skilled foreign workers,” he said.

The number of Malaysian graduates in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) is still below its target of 60%. To close the gap, the government is improving its technical and vocational education and training through advancing industry engagement.

The global competition for talent in the semiconductor industry is white hot, and the relatively lower salaries in Malaysia is contributing to a brain drain.

Chow said that the government is aware of the issue and has taken measures to raise salaries. He said, “At present, starting salaries for engineering graduates has increased from 3,000 ringgit plus to around 4,500 ringgit. The government has also set up scholarships and is promoting vocational training. These are all efforts we are making to overcome the talent shortage.”

He is also calling on employers to join in the effort to raise engineering salaries, to avoid a loss in the industry’s competitiveness due to brain drain.

Attracting external talents and encouraging overseas professionals to return

Chow said that Penang’s industrial development over the years has nurtured many outstanding talents for MNCs. He shared, “When I visited some big companies in Penang, I discovered that apart from a small number of high-level management talent who are foreigners, the rest of the staff was Malaysian. This shows that we have talent, and we need to attract them to work for local firms.”

He said to reverse the brain drain, the government has stepped up its efforts to encourage more talent to return to Malaysia.

“We hope that one day Malaysian firms can also become big names in the semiconductor industry. Otherwise, Malaysians will always be cheap labour for MNCs. This is not what we want to see,” he said.

This article was first published in Lianhe Zaobao as “重振“东方硅谷”地位 槟城引领马国半导体发展”.

![[Big read] When the Arctic opens, what happens to Singapore?](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/da65edebca34645c711c55e83e9877109b3c53847ebb1305573974651df1d13a)

![[Video] George Yeo: America’s deep pain — and why China won’t colonise](https://cassette.sphdigital.com.sg/image/thinkchina/15083e45d96c12390bdea6af2daf19fd9fcd875aa44a0f92796f34e3dad561cc)